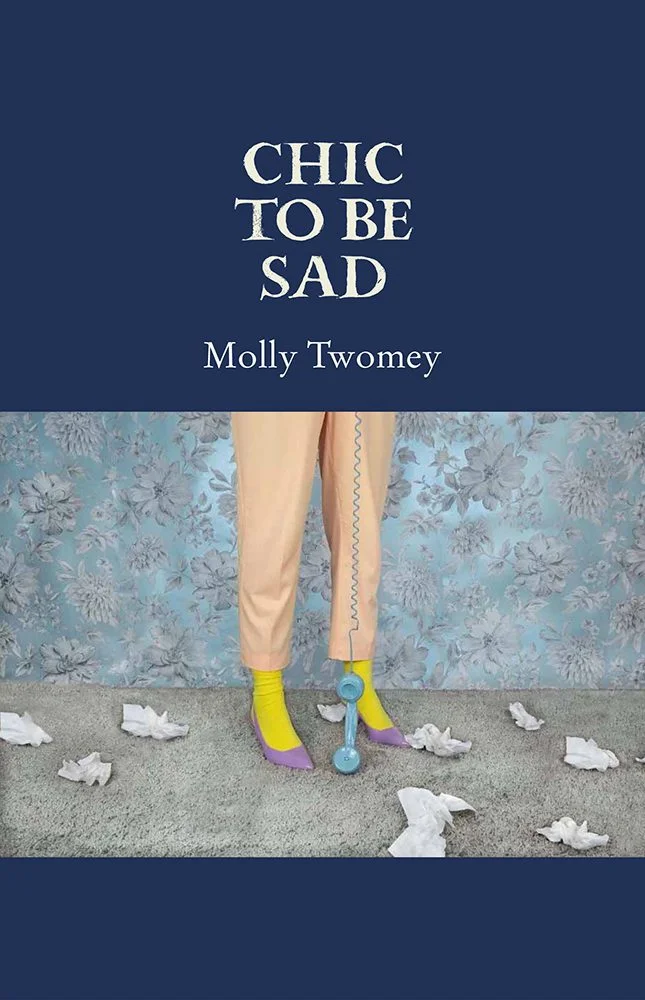

Molly Twomey’s Chic To Be Sad

The Gallery Press, Ireland

July 17, 2025

72 pgs.

Hardback: €19.50

Paperback: €12.95

One of Ireland’s New Clarion Voices: Molly Twomey’s Chic To Be Sad

For me, as a child of the ‘80s and teen of the ‘90s, it often felt as though occupying a female body was the equivalent of wearing a grenade. How one dressed and appeared, slid by unnoticed or got harassed on the city bus, in school, at sports practice, on the sidewalk, or at the grocery store was an inevitable, unavoidable part of being female—even after my parents moved to a sedately prim suburb with an enviably low crime rate. I was eleven when a classmate’s father leered at me during basketball practice and commented, as I left the court, that I had a “beautiful figure” when I was, in fact, a skinny preteen as confused by this unwanted attention as I was about how to shave my legs. (For reasons I can’t explain, I’d thought it was only the shins.)

Local guides for weathering girlhood into adulthood—TEEN magazine or an older cousin unafraid to share the score—left a lot unspecified. I had my Catholic school’s virtual deification of the Virgin Mary on the one hand and the song lyrics to Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” on the other. The actual geography of adolescence was the terra incognita in between, and it’s this territory, for the Gen Z generation (born, roughly, between 1995 and 2014), that the young Irish poet Molly Twomey takes as her subject in Chic To Be Sad, her much anticipated second collection from Gallery Press.

The collection begins with a conflagration: a housefire that suddenly reduces her childhood home to ash and ruins, one from which her younger siblings and parents narrowly escape. The fire also burns the theater of her adolescence, one that Twomey herself barely survived. As she alludes to in the opening poem and details in her first collection, Raised Among Vultures (2022), she suffered from anorexia nervosa, still the most fatal of psychiatric disorders, one that often implicates the hard-baked misogyny of Western culture as much as it does personal etiology. Twomey details the strangeness of seeing the house, emblematic of her years of desperate struggle, burn to the ground.

At some point

our house became a bath

I failed to drown in,

a kitchen table where I faked concern

for my bones like chalk

under constant threat of rain.

It’s where I tore my baby fat

out of albums, clamped my ravenous tongue.

I should be sad to see it all burn,

to never reopen the scorched diaries

of calories and hip breadth.

Twomey, grateful that her family escaped the flames unharmed, feels a complex grief for the artifacts of her illness. The demise of that house—its charred ruins—brings her back to the mise-en-scène of her disorder and to the ignorant or ill-advised counsel she received as she sought healing.

In the poem “Playwriting,” for example, she describes a university writing professor who suggests that she kill off her script’s protagonist with an “ice-cream cone of pills” since “no audience wants / to hear of her malnourished dreams / and blacked-out mornings” as if the travails of illness couldn’t be as poignant, gripping, and literary as tales of a murderous coup or bank heist. Twomey joins Virginia Woolf (and others) in asserting that illness is a major theme or, as Woolf quips memorably in her essay “On Being Ill,” it is when “the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries…are then disclosed.” Returning to health, Twomey has brought back the news from the country she discovered and a gimlet eye, poised to see through the paradoxes—and falsities—of contemporary culture.

Emerging like Aeneas from burning Troy, Twomey’s narrator recounts, both directly and obliquely, the painstaking recovery she has made from the brink of self-destruction. In the short lyric “The Saga,” she suggests that it is art, in otherwise dire circumstances, that serves as salve.

All I know

of the mess I’m enlisted for—

food trays used as bomb shields,

wounds like gaping mouths of lampreys.

I pack the violin, its bow, a bone saw

among my uniform, needles, muslin.

Animating the perspective of Elizabeth Kelly, a nurse given a violin from an abandoned ship, The Saga, which drifted ashore Ballycotton in 1895, Twomey recounts that Kelly brought the violin to France where she served during World War I, witnessing the tide of mass destruction that forever changed the landscape of European history and humanistic hope in liberal progress.

Twomey’s persona poems illustrate her talent for redoubled narrative; this collection also features a poem from “the citizen’s wife” in James Joyce’s Ulysses and a poem in the voice of Darlughdach, the younger nun who was the beloved soulmate of Saint Brigid. In the latter, Darlughdach tires of waiting for Brigid’s amorous attention and seeks out another lover, using contemporary means.

Sick of waiting for your touch,

chewing the inside

of my cheek into a pink honeycomb,

I meet a man online […]

I think of all I might lose—our small bowls

of fried scallops, our shared life, the lease.

Weighing the comforts of shared domesticity against the need for erotic thrill, Twomey plumbs the shadowlands of eros. She also looks carefully at the dangers that lurk in such forays as well as the peril, for women, in more ordinary transactions. In “Aldi Car Park, Youghal,” she writes of looking for an affordable apartment, one without a leaking roof. When the narrator meets “a landlord in his Hyundai,” she tries not to flinch when he brazenly notes that she is “prettier than expected” and puts “his hand on my knee, / sealed as a caul on a newborn skull.” The casual predation women endure in seeking basic security, education, or employment is one of Twomey’s recurrent motifs, skillfully explored in this collection, forcing us to grapple with its cumulative psychological price.

Twomey’s first book, also published by the prestigious Gallery Press, vaulted her to the forefront of poetry in Ireland three years ago: Raised Among Vultures was shortlisted for the Seamus Heaney Prize for Best First Collection, and it won the Southword Debut Collection Poetry Award. When a poet skips the queue, writing a first collection that garners regional or national acclaim, there is tremendous pressure as she composes the next volume. But Twomey shows that such expectation can be lightly born and duly answered: Chic To Be Sad marks an expansion of her powers and continuing proof of her promise, all while working the furrows of her previous accomplishment, the significant ground broken in her first book.

In one of my favorite poems in her new collection, “I Ask Levenshulme High School Girls What Boils Their Blood,” the narrator conducts a writing workshop with adolescent girls in which she asks them to catalogue what enrages them. Their quirky answers include “buttons that fall off shirts,” a grandmother who pinches her granddaughter’s soft stomach, “Islamophobia,” and “unsolicited advice,” among other chronic annoyances. Twomey’s narrator also asks what they are “obsessed with,” and the innocence of the girls’ answers is heartbreaking: “‘half-zips, chicken tenders, hairbrushes that don’t break.’”

Serving as their creative instructor, the narrator swallows the “warnings” that she might, as an older (but still young) woman, wish to give them about strategies for fending off assault. Quietly, she dreams of a future “where none of them ever drags / back the morning to see their blood / swept up, torn skirts lifted and binned.” Twomey reminds us that somehow, for all our modernity, we have not yet provided women with assured freedom from physical assault and its ongoing fear, against which most women learn to measure their activities.

As a generation of women in Ireland and in the U.S. comes of age in the wake of MeToo—and the ultra-conservative backlash with its tradwives, attacks on birth control and reproductive choice, and “MRS degree” rhetoric—we need poets willing to write, as Eavan Boland, Michael Longley, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, and Seamus Heaney were, into the fray of politics and history as well as into the hope and suffering of contemporary life. Twomey, and her growing international readership, should take heart in the delivery of this splendid collection in all its rich rewards and look forward to the broadening compass of her art.

Molly Twomey’s Chic To Be Sad can be purchased here at Gallery Press.