Sad Animal

by Joshua McKinney

Joshua McKinney exhibits an awareness of the world and examines everyday fears, both personal and existential, in his latest book, Sad Animal, Gunpowder Press, 2024. His scale of focus ranges from the infinitesimal to the infinite as his poems explore interpersonal relationships, interspecies relationships, the complexities of environmental devastation, and the pervasiveness and destruction of war. They also peer deep into humankind’s interactions with nature.

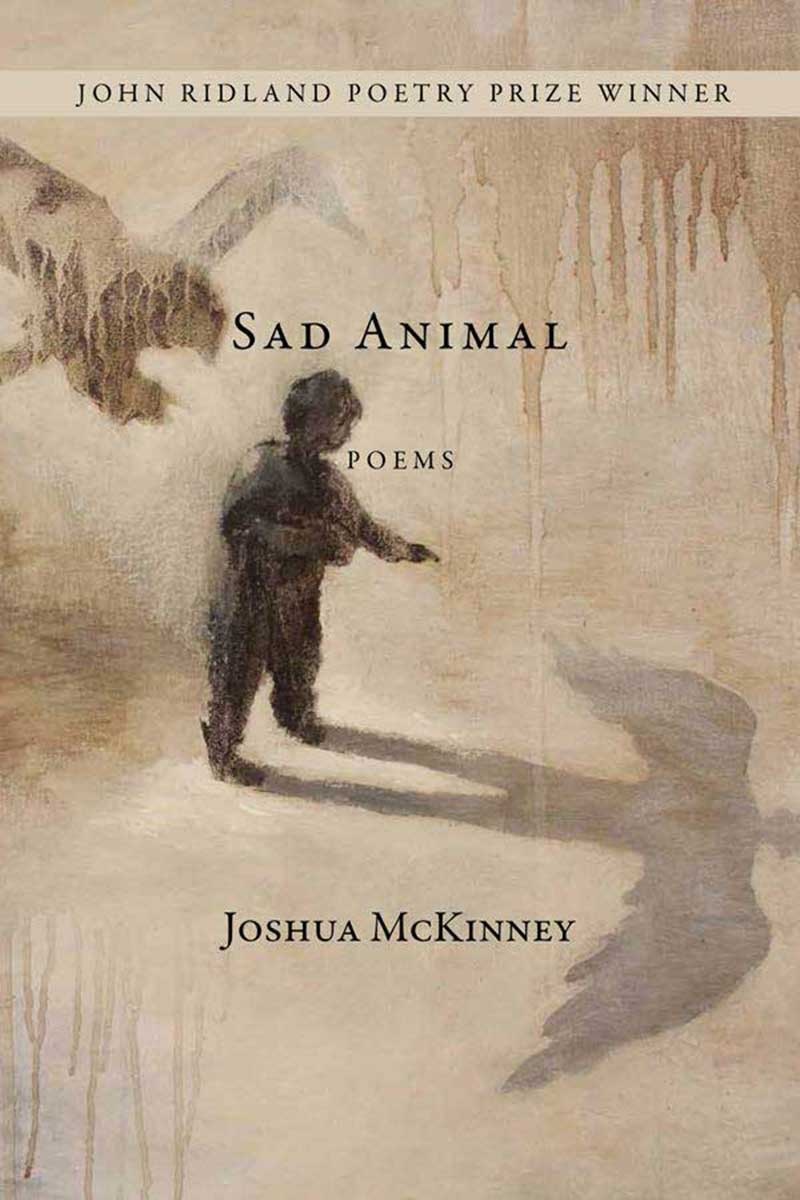

The journey of Sad Animal begins with its metaphorical cover, a monochrome of water color shadows. In sepia there is the figure of a raptor hovering over a boy. Lit from behind, their shadows are cast together on the ground and united as angel wings on a human. Ambiguously, the figure of the boy is pointing or holding a gun in his left hand at the shadow. Nature is hovering over us, talons open, as humankind simultaneously shoots and kills it. As illustrated by the cover, McKinney’s poems are strong with intent supported by imagery. The poem addressing these specific images, is the poem, “Shade,”

A man thinks he owns his form,

that his shadow is his alone,

that his body, its flesh and bone,

obstructs the light in his image,

when in fact, he possesses nothing.

The shadow casts the man.

“Shade” is one of a number of pithy poems containing six lines that fracture the overall composition of the book by acting as unofficial section dividers and providing contrapuntal relief to more complex poems. Though their images and brevity provide a contrast to the longer poems contained in the book, their impact is not minimal.

McKinney loves language. He has an affinity for sophisticated vocabulary, using it judiciously to emphasize ideas and concepts. When he examines the complexity of human interaction with nature, he includes scientific terms as illustrated by his four-part haibun which incorporates knowledge of nature, history, geography, and interpersonal relationships. That series closes with a mournful haiku:

Asleep in my chair,

I remember the flowers.

Please tell me their names.

We become sad animals passively noting a changing world.

Comic relief from the book’s existential angst is apparent in the poem, “Men of Letters,” which provides a description of a fist-fight between Wallace Stevens and Ernest Hemingway stating it was,

…a great symbolic bout: Poetry vs. Prose…

It concludes with McKinney’s speaker’s voice, buried in an ambiguity of age and climate despair dreaming of two great writers:

…In a mind of winter, I am dreaming of lions.

There is music in McKinney’s poetry. Even in the poem of self-immolation, that of the suicide of Thích Quang Ðűc, “In Perpetuum,” the description of death is beautiful:

…still, as frozen amid tongues of corybantic flame

he sits silent and unmoving, save for

the raging action of his stillness. The living

heat arrested as, leaping, it seizes him, appears

also to emanate from the monk as if some long restraint

has given way, the flames bursting forth and

absconding skyward with the coiling smoke.

Thus the stunned aperture captures a world

in black and white, no color and all color…

The reader either remembers the scene vividly, reliving it, or suffers it for the first time in eviscerating detail. But this death is not the only death by burning in Sad Animal, it is the only one by choice. The poem, “When Paradise Burned,” brings home the horror of wildfires related to climate change, and how humankind has to modify its existence in the face of this threat:

…Neighbors, it touched us all,

of that we had no doubt. For a time, even the young

among us took on a new awareness of air,

of how we were drawing into ourselves

things transformed in the flames, entire towns

incinerated, their components rendered particulate—…

It concludes with the warning:

…Take this knowledge you refuse to know. Take this,

this unbearable thing. Now it belongs to you.

McKinney’s speaker hands responsibility for the state of the earth to the reader. There can be no evasion:

…Now it belongs to you.

Sad Animal presents humankind as a creature who mourns losses on a personal level, and also, as a species, irreversible changes in our world. The poetry in this volume is poignant, vibrant with alliteration and emotion. It is a call to awareness and hopefully action as well as an appreciation of what we have.

The book concludes with two poems. The penultimate poem is “The Cause,” a third person account of Orpheus on his way out of Hades, his experiences iterated with a strong sense of interiority until the final few lines of the second stanza:

…All this

he’d done through desire

born of loss. He saw that now.

The poet’s true muse isn’t love,

it’s lack. It caused his fame.

It was his cause, an endless source

of song. Nearly out,

he paused.

It’s this pause, the lack of conviction that dooms Orpheus, and (in the greater scheme of things), our world.

Yet the final poem, “Allure,” provides hope through the manifestation of a hawk at the roadside during the inanity of rush hour traffic. Nature draws the attention of the speaker who

expresses it thusly:

…Inviolable good has drawn

my busted eyes into

the mirror of my passing,

where plume-sheen

dazzles in last-light,

and my ravening,

parched heart leaps

into the air.

Despite the frailty of the human, nature, and the world itself, hope is spread as a welcome mat for the reader.