Peter Johnson’s self-effacing personal essay for this month’s issue of Plume recounts a coming-of-age episode with comedic sprezzaturra. In “confessing” the colorful, absurd, topical facts of his youthful soul-searching during the sixties, Johnson opens a wide window onto the makings of his eventual career as one of America’s supreme prose poets—“a literary son”, no less, of Russell Edson. Part prose poem, part mini-memoir, Johnson’s essay recounts the familial story of his naming and then subsequent adolescent soul-searching that has continued now for over five decades in a continual series of spare, risible pericopes that cross over both fictively and confessionally to his reader from a unique and always ironic distance from himself.

–Chard deNiord

“My Name, a Nun, St. Peter’s Chair, and Literary Fame—Not Necessarily in That Order”

Consider the following prose poem, titled, “Names”:

My mother named me Peter because I was born on the feast of St. Peter’s Chair and thus have always felt sat upon. A few announcements: first, this new baby was not on the syllabus; second, we will not call him Luc or Etienne, neither of which most people can pronounce. He will be named Lucas, after The Rifleman—an allusion unfamiliar to most young poets, especially the one who said, “No one reads Robert Frost anymore.” To him I bequeath my three-iron, which I haven’t hit straight in twenty-five years. I used to hold my toy rifle like Lucas McCain. I was into coconut then. Now, I’m mostly an apple-and-banana guy, yet I still feel sat upon, and no award will ever change that. I once read a book called The Two Thousand Names of God, but can He hit a wedge in the rain with backspin? Can He drain a thirty-foot putt with Beelzebub heckling him from a nearby bunker? I hereby report that I have a wife, two sons, and a dog. I am not sympathetic to inanimate objects, and nothing will ever change that. For my Confirmation, I tried on the name Mario, but my father forbade me to wear it. Born Louis, he changed his name to John. It took me twenty years to discover that. What more can I tell you? What more do you want?

I’ve often thought I’d be a famous writer if I had been given a different name. Who’s going to reach for a book written by someone with a name as ho-hum as Peter Johnson. Why couldn’t my parents have named me Titus or Axel or Blaze—tough-guy names like that? Even Caspian would have been cool. There’s something ancient and exotic about Caspian, yet also lyrical in the way it slides off one’s tongue.

It could be worse, though. My sister was named Judy, my father, John, and my mother, Jeanne. If a Judy or a Jeanne Johnson showed up uninvited at my front door, I’d expect them to be well-groomed and wearing pill box hats, bent on offering me a free introductory facial, or handing me a pamphlet that insists, in spite of my many personal failings, that Jesus loves me and that there’s still time to save my sad-sick soul.

Although my father didn’t escape the dreaded “J” pathology, in a way, he still lucked out because everyone called him Jack. So he was “Jack Johnson,” which brought back memories of the iconic black boxer who, in the “fight of century,” pummeled James J. Jeffries for fifteen rounds, much to the horror of most white Americans. At the time of that fight, my father hadn’t been born, but I’m convinced he would have appreciated his namesake’s achievement. Like most white guys of his generation, my father was capable of the occasional ignorant comment about blacks, but no one, especially the black guys he worked with in the steel plant, would have called him a racist. In fact, if he and of his Irish cronies had a prejudice, it was against Italians, always pronounced “Eye-talians.” To make matters worse, like the legendary Jack Johnson, my father had been a boxer in the Navy, losing only once to an “Eye-talian” half his size, named Rabbit-Nose Alfonse (now there’s a name for you), and that first-round, 30-second knockout had always haunted him.

For me, perhaps worse than having a boring name like Peter was knowing how I got it. I was supposed to be called Jeffrey (there’s that “J” again). You could argue that Peter is certainly much better than Jeffrey, but I’d argue back that your first name has meaning because of what you associate it with. I associate mine with a nun and a chair. After I was born, a nun approached my mother and informed her that I was brought forth on the Feast of St. Peter’s Chair. I’ve never asked for the name of this nun. Many cultures believe that knowing someone’s name gives you incredible power over them, and who knows what I might wish upon the soul of this long-dead, well-intentioned nun.

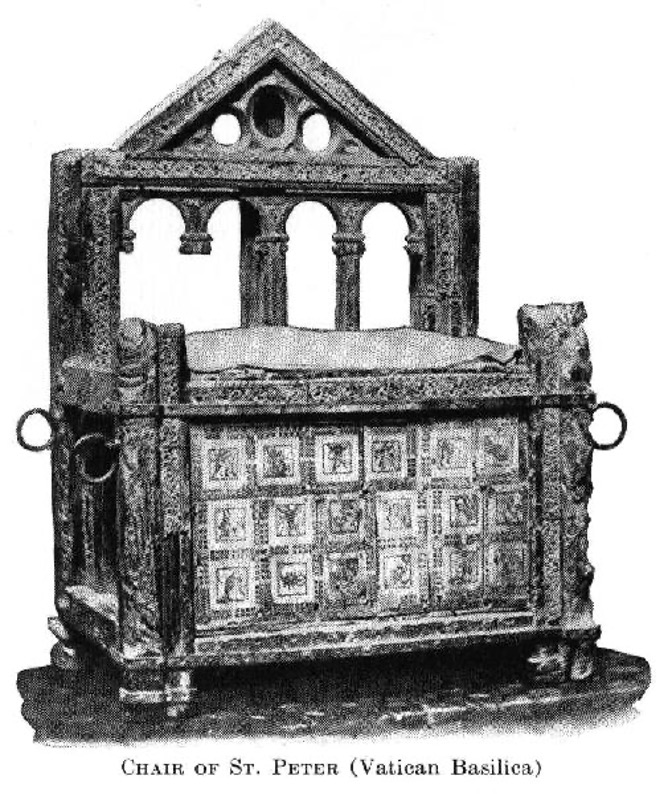

Just in case you’re wondering, the feast of St. Peter’s Chair takes place on February 22. The chair itself was originally a wooden relic, gifted from the Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Bald to Pope John VIII in 875 A.D. Supposedly, it was St. Peter’s actual throne, and according to Pope Benedict XVI, it was “a symbol of the special mission of Peter and his successors to tend to Christ’s flock, keeping it united in faith and in charity.”

This is all very interesting, but a chair is still a chair, and few people even care about St. Peter anymore. In fact, most of them haven’t been to church or read the Bible (or any holy book) since they were forced to as kids. For them, Sundays are about sleeping in, Pilates class, streaming TV series, or buying chips and beer for their favorite football game.

Once, though, for about three months, I almost became someone else. I was nineteen and working as a carpenter in Denver, convinced I was destined to be the next great poet or novelist, even though I was drunk or stoned most of the time. It was 1970 and we were all fools. We weren’t politically motivated or trying to save the world, as some of my baby boomer friends insist. Refusing to get a haircut, working construction, and playing darts all night while downing shots of tequila wasn’t going to save anyone. Besides featuring shoulder-length hair, I wore a wooden cross the size of a padlock around my neck. I wasn’t religious. I just thought it looked cool. I also favored a cowboy hat I had bought at Disneyland. It was in good shape when I purchased it, but by the time I got to Colorado, it was so worn and floppy—not to mention the color of dog scat—that I looked more like Jed Clampett than Clint Eastwood.

But it was in Colorado where I adopted the name “Blue.” There, one of my construction foremen, despite my fair hair and blue eyes, had gotten it into his head that I was Native American. The news spread, and I discovered it was hipper to be an “Indian” than a nineteen-year-old Irish Catholic kid wandering around the country wondering who the hell he was. So one day at lunch, my dopey friends and I decided to rename ourselves, and this little guy with a blond ponytail, whose name was Paco, said I looked like a “Blue.” Paco, a notorious nomad and a voracious reader, explained that in Native American culture blue symbolized wisdom, so I was told to either agree to “Blue” or he’d rename me “Coyote.” Consequently, Blue stuck until I flew home to Buffalo a few months later, moved back in with my parents for the fourth time in two years, and was exposed as the boring Peter I was.

Now, at seventy-four, I’ve come to believe that I was never going to be named Jeffrey in the first place, and that my mother, an extremely kind person, lied to spare me more heartache. She knew that a bland name like Jeffrey would make Peter seem more significant. I’m also convinced the rest of the family is aware of this deception because whenever I bring up my sick obsession, usually after my fourth rum and Coke, everyone begins to scowl or squirm, scattering as if someone’s just passed gas and doesn’t want to accept responsibility for it.

I can only wonder what name the good Lord would have implanted in my mother’s head, if Fate hadn’t intervened. I wonder what memorable name had gotten scrapped and tossed into the ash heap of family history—all because of a nun with an obsession for the General Roman Calendar. I’m sure it was an Irish name, something like Caedmon, or Fergus, or Eamon, or, even better, Moriarty. Yeah, Moriarty Johnson.

Imagine that name in bold red letters blistering the spine of my first book of poems.

What reader would not grab that masterpiece off a bookshelf?

Certainly, my place among the Great Ones would have been assured.