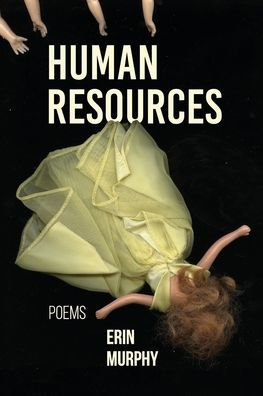

Human Resources by Erin C. Murphy

Grayson Books

June, 2025

During the Great Depression, two subsidiaries of Union Carbide, now itself a subsidiary of Dow Chemical Company, began digging a tunnel to divert a river so that the river could be used to power a factory. There are several kinds of diversions at work in the foregoing sentence. One is the obvious one involving the river, which is one of the oldest rivers in the world even though it’s called New River. Another involves the work of misdirection, what lawyers call “risk management.” By lawyers, I mean lawyers like me. I implicate myself within the harms done by my colleagues at the bar applying the common law, which tends to not benefit common people. Union Carbide formed the New River Power Company to “oversee” the tunnel project; when a corporation makes a subsidiary it can make the subsidiary go away when it wants to, or when it needs to, as when the facts of the Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster came to light and miners, many of whom were Black, began dying of silicosis. The men worked without masks or respirators. One of the first to write about the incident – to document it – was the poet Muriel Rukeyser. She titled her poem about the disaster, “The Book of the Dead.”

Is work in the United States any safer almost one hundred years later? It depends on what you mean by “safe” and it depends on what kind of work you mean, but not really. In the 1970’s and 1980’s men and women began dying from mesothelioma, another grim lung disease. Shipbuilders, welders, plumbers, just about every trade imaginable worked inside clouds of asbestos dust for years without safety equipment. They brought the dust home on their clothes and their wives put the clothes into the laundry. Eventually it became clear that companies hadn’t merely ignored lessons from Hawks Nest when they put asbestos into everything from putty to ceiling tiles. They just learned how better to hide from responsibility, instructing company doctors and even a major life insurance company to hide statistics and bury reports. The only real question about occupational safety – especially now, with federal agencies being stripped to the bones or dismantled altogether – is what will kill our workers next.

This means documentary art of every kind, including poetry, is necessary. Someone needs to record what’s happening, especially since a certain quasi-government agency began deleting records from government websites. There will be no WPA employees this time around to take photos in the dust bowls. Erin Murphy’s poetry collection, Human Resources, engages with work performed in fields, in ramshackle warehouses, and on assembly lines, spoken in the voices of the workers themselves in many cases as in “Imperial Valley:”

They import gringa packers

by the cartload from Fresno,

but most of us come from

over the border, whole families

sleeping in ditch bank shacks

on tenant farms. Our niños

work the fields, too. By evening

they’re sunburned and spent, dead

weight in their mothers’ arms.

Early spring when the ground

is greedy with heat, we plant

cotton. Too soon and the stalks

are stunted like grown boys

who never got enough to eat.

These persona poems converse with erasures drawn from human resources manuals, company “guides” written by people whose work it is to guide the company, not its workers. Some of these poems are positively surreal. I kept thinking of Lumon Industries from the streaming series Severance, its unknowing employees watched over by knowing supervisors, all of them speaking weird corporate double-speak like this language from Murphy’s poem, “HR Erasure: Policy on Drug and Alcohol Use”:

The company tolerates

impaired workers.

You are under

the influence.

You are under

the influence

of Human Resources.

In many countries, and particularly in the United States, work culture is the only culture, meaning that it is a cult.

Exploitative work occurs everywhere and during every time, and for reasons not limited to race or class. “Schuhläufer” means “shoe runner.” The Nazis forced prisoners at the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camp to test the soles of military boots. Around twenty prisoners died every day marching on a test track while carrying twenty-five-pound packs. German shoe manufacturers Salamander and Leiser, still in profit today, sent prototypes of their boots to the camp for testing and paid a fee to the Nazis for this “service.” A poem in the collection titled “Schuhläufer” movingly shrinks the distance between the prisoners and the products of their forced labor:

How long will a pair of shoes last?

Days, weeks, months? The testers run

[. . . .]

[. . .] Months, weeks, days, hours:

how long, how long will they last?

The events of the poems and their consequences are often so visceral, so infuriating, that it is easy to miss their music. Murphy wisely composes in the many voices of her speakers, permitting them to sing out and be heard above the static din of corporate-legal speak. The blown-to-bits, spacey HR erasure poems, in particular, make a lot of white noise against which human voices can be foregrounded. It is an extraordinary relief to emerge from the cubicle and into the sound of a poem like “Indigo,” whose speaker, an enslaved person, describes life around the house where she is made to work. “Nobody wants to see how it got done,” she intones twice, describing the stealthy means by which she and others clean doorknobs, butcher animals, and churn sugar, careful not to draw too much attention.

A man named Living. A woman named Time.

A girl named Girl. A boy named Son.

And me, Indigo. Indigo trade. Indigo dye.

Nobody wants to see how it got done.

In “Raise the Rent,” the music is even more explicit, joy-inflected, the song of the early side-hustle: tenants in East Harlem who throw a party and charge money at the door to pay the rent. Meanwhile, “Senate Bill 739, 1893” adopts a properly legislative tone, sans joy, sans any satisfaction at all, just as the bill the poem references established the Labor Day holiday: “a legal / public day to save // on washers and dryers / and jewelry and tools”. The system wouldn’t work without its carrots, even if the carrot we already have tastes fine.

Some documentary-style storytelling refuses to choose a side, and some veers annoyingly into didacticism. Murphy avoids both these pitfalls by declining to make resources of her human subjects. They speak for themselves, and beautifully. The standout poem in this book, at least for me, is “End of the Season,” not least because I immediately recognized its Rehoboth Beach setting. (The now-closed lesbian bar mentioned in the poem was called The Frogg Pond with two g’s, not one, but it’s ok, I miss the old scene, too, and it was indeed a great bar.) Rehoboth might rock the most fantastic American-flags-draped-around-a-Victorian-style-bandstand-on-the-4th-of-July-but-gay vibes imaginable, but it is surrounded by soybean fields, pick-up trucks and Let’s Go Brandon signs. It is, in other words, a good metaphor for the current state of things, driven by late-stage capitalism and weaponization of much of the working class by fascists and billionaires. We now have fact-checkers for fact-checkers in much the same way that poll watchers used to stare at one another while the hanging chads were counted.

On this foggy day, the ocean

and sky merged at the seam.

I read that something like this

caused JFK, Jr.’s plane crash

off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard

—he may have been unable

to tell which way was up.

Spatial disorientation, they call it.

There are a lot of references

to U.S. presidents in this poem,

presidents who—while not

perfect—seemed like they were

trying to steer our country

away—not toward—darkness.

They are ghosts now, like so many

landmarks that have closed.

[. . .]

When your children grow up

and leave home, everything

is a ghost landmark. Every memory

can make you half laugh, half cry.

The horizon is a blue blur. It’s hard

to tell sky from sea, sea from sky.

The poems in Human Resources are thoughtful, layered, and, for the right reasons, heart breaking. Someone, someday, somewhere should be able to read about what we were like when we were like this.