A Conversation With Mai Der Vang

On the Occasion of the Publication of Her Third Book: Primordial

by Frances Richey

Mai Der Vang and I met in 2009 at Hedgebrook, a residency for women writers on Whidbey Island off the coast of Washington State. Once a week, for a month, we came together with our five fellow residents and read from our most recent works. From Mai Der, I learned about her people, the Hmong people, many of whom immigrated from Laos, as her parents did, to the United States as refugees after the Vietnam War. Before Mai Der was born, The US conducted a secret war in Laos using Hmong warriors as proxies, in many cases forcing these men into battle. I had never heard the word, Hmong, before I met Mai Der.

Eighteen years later Mai Der has written three collections of award-winning poetry, masterfully interweaving her own family history with the deepest passages of Hmong history and traditions. Her three books, which I recommend reading in order of their publication, bring to life a hidden world of lost landscapes, a mysterious animal known as Saola and beloved ancestors from Southeast Asia, a people trying to find peaceful agrarian lives amidst the danger and outrage of continuous wars, always on the run in their struggle, over centuries, to survive.

It has been a deep pleasure to reunite with Mai Der after all these years to discuss her books, Afterland, Yellow Rain, and Primordial. Our experience in conversation, after reading her books, reminds me of something Jack Gilbert said about one of his own poems in an interview with The Paris Review:

“It’s…sad and tender. A truly adult dream. Profound tenderness…That’s what I like to write as poems. Not because it’s sad, but because it matters.”

~

FR: Congratulations on your new book, Primordial!

MDV: Thank you.

FR: I read your first two books back when they came out, Afterland and Yellow Rain. But it’s been quite an experience to close-read all three of your books in order of their publications. I have to say, in order, they are even more powerful. You’re bringing to life and keeping alive a whole culture and interweaving some of your own family history with the larger story of the Hmong people.

Did you foresee these three books in the order that they’re in, or did each come on its own triggered by something that you weren’t planning, or didn’t expect?

MDV: I had no idea the books were going to come about as they did. I can never tell where the work will go until I actually do it. I started with Afterland, and there’s a poem in there about yellow rain. There’s also a poem that references an animal called Saola. I had no idea when I was assembling that first book that I would eventually write something much fuller on yellow rain or that I would even go as far as writing about Saola. With Afterland, I was still figuring things out, as I still am today with my work, and the poems came about naturally.

Yellow rain was a topic that stayed with me even when I was writing Afterland. I knew there was more to yellow rain that needed digging and investigation. I also knew I would come back to yellow rain at some point, but I didn’t think it would become my second book. I spent nearly a decade immersed in the research and the government archives to bring that body of work together.

My third book, about Saola, threads back to my first book. I think Saola is mentioned in Yellow Rain as well. It’s funny how the books thread together through subtle references or unintentional moments of foreshadowing. Primordial came together because I had been thinking about Saola for years and thinking about its connection to survival, the refugee, and the Hmong experience.

FR: These books clearly required a lot of research. Do you enjoy research?

MDV: I’ve come to appreciate it. I didn’t set out initially to do this much research, especially when I was writing Yellow Rain, but the research became the bulk of the work in crafting the poems. I had to bring myself to a level of awareness and knowledge around the topic and its complicated history in order to write about it. The research also helped me think through the parts that were missing from the “official” narrative so as to offer another version on yellow rain.

FR: Exactly what is yellow rain?

MDV: Yellow rain is a chemical biological weapon that was used against Hmong refugees when they fled Laos after the United States withdrew from its wars in Laos and Vietnam. The issue of yellow rain drew conflict between both sides of government with one side exploiting the charges to lobby for increased weapons funding and production while the other side dismissed the charges claiming the mysterious substance had been nothing other than the feces of honeybees defecating en masse. Those advocating the bee feces theory were eager to deescalate the war, and the discovery of yellow rain would only dampen their efforts. They began a campaign to invalidate the Hmong testimonies, which was an erasure of sorts, in my opinion, the gaslighting of a people and the discrediting of their trauma and losses. The two sides continued to bicker all the while in this great mess of political scheming and Cold War theatrics, the Hmong testimonies receded further into the background. The government estimates that over 6,000 refugees died from yellow rain while other reports indicate far higher casualties.

FR: Did you have to travel to get to the various archives? Did you go to specific libraries or museums?

MDV: I spent a week at the National Security Archive at George Washington University. They have an expansive archive of declassified materials and documents related to yellow rain and the Cold War. I dug through boxes of old paperwork, handwritten notes, and newspaper articles, and scanned about two thousands pages to take back with me. I also connected with a professor at Georgetown who is an epidemiologist. She completed her dissertation on yellow rain, and she helped me get access to virtual files that she helped declassify. The files included charts and documents reporting the results of biomedical and environmental samples that had been tested for yellow rain, along with a host of other materials.

FR: Did you ever have the feeling or sense that you were being guided? That there was an unseen hand helping you?

MDV: I felt the guidance intuitively, and speaking as someone who grew up in a family that practices shamanism, I would add that I felt guided by my ancestors who helped me believe that something was going to be there for me to find on the other side. Being immersed in the documents, the language, the technical terminology, the imagery, the medical reports, I felt transported. I had entered a new space, and as an outsider to that space, I was in a position to look at everything from a different perspective.

FR: I had that feeling as I was reading the poems, that I was entering a different universe. I was wondering if Shamanism was the religion of the original Hmong.

MDV: I would say shamanism was once the dominant belief system for most Hmong, especially when there were larger populations of Hmong in Laos and in southwest China prior to Laos. Shamanism is the practice of acknowledging and communing with the spirit and ancestral world. It wasn’t until after the war and when Hmong were resettled here in the United States that many of them converted to Christianity due to refugee sponsorship from churches and religious organizations. As a result of conversion, there are pockets of Hmong who are rooted in church communities, but there are still many families, like my own, that continue to practice the old ways.

FR: What are the old ways?

MDV: The old ways being the practice of honoring and feeding one’s ancestors through rituals and ceremonies. In my family, we’ve held rituals where we literally put down plates for the ancestors who, in spirit, come and join the feast. Other ceremonies include “hu plig” which is the act of calling the spirit of a newborn baby to join the family’s spirits. Funerals are rooted in complex ritual, too, since Hmong believe when you die and cross over, you return to live with your ancestors, and the ceremony, which happens over the course of several days, is the enactment of your spirit’s journey back to the ancestors. Hmong practices also incorporate aspects of animism which is the belief that everything around us has a spirit, the trees, the rocks, the rivers, all have their own spirits. When you’re out in nature, you’re surrounded by these spirits, and you should behave in a respectful manner so as not to disturb them.

FR: And there’s nothing like a war to destroy all of that. I wonder what it was like for the Hmong who were in Laos when the secret war started…I’m not sure when it started, sometime in the sixties or early seventies? I remember hearing about the CIA and the Secret War, but I had no idea, as a teenager, that the CIA was recruiting Laotian men to fight that war in place of American soldiers. And then the US abandoned them when the war was over. Was there a moment when someone had conscience enough to help those who were left? And families of those who fought? To help them to immigrate either to the states or somewhere safe from yellow rain and that sort of thing?

MDV: The war started in the early-1960s, but it had been ramping up since the mid-1950s. It ended in 1975 with the communist victory and the U.S.’s withdrawal from Vietnam and Laos. The war in Laos became known as the “Secret War” and it was a sideshow to the larger war in Vietnam. The Americans had hoped to use Laos as a buffer to prevent the spread of communism into Thailand. The CIA went into Laos and enlisted and used Laotian civilians, many of whom were Hmong tribesmen, to serve in this war and fight on behalf of the United States as a proxy army. Laos was supposed to be a neutral zone, but the United States got around that by conducting proxy warfare using the local tribesmen to do their war bidding. In other words, they used Hmong lives to spare American lives. When the Americans ended the war, Hmong people were left behind to fend for themselves. I often think about how it must have been easier for the Americans to abandon a war that had been conducted covertly or that wasn’t supposed to have happened anyway.

After the war, people fled through the forests and traveled on foot for days and weeks to arrive at the refugee camps in Thailand, my parents and grandparents included. Even as there were still a few American officials in Laos, many had already evacuated. Some of these officials understood the deep sense of betrayal their own government had inflicted upon Hmong.

FR: Are you talking about the American soldiers here?

MDV: Yes, soldiers and CIA officials. Some of them did establish a connection and friendship with Hmong, but the larger story is that they left anyway, and Hmong were alone to defend themselves against Communists who sought retribution.

FR: I remember watching the evacuation from Vietnam on television. My son was born in 1974, so he was a baby when all that was happening. It’s still vivid in my mind. Especially the people left behind in Vietnam. I think most people in the States knew nothing of the plight of the abandoned Hmong.

I had never heard the word Hmong until 2009 when I met you at Hedgebrook. I was ignorant of any details about Laos during the war. Now, having read your books and being able to have this conversation and ask questions, you have expanded my understanding of all those hidden parts of the war that were so shameful. My son was born as it was ending, which marks that time for me in a very personal way. I knew guys in high school in the late sixties who were sent to Vietnam with no understanding at all as to why we were there. They had no choice. The ones I knew who made it back were deeply damaged. It was all so mysterious and murky.

MDV: I imagine it was intentionally murky.

FR: You’ve mentioned the words tribesmen and tribal when speaking about the Hmong, and I read somewhere that the Hmong didn’t have a written language until the 1950’s Is that right?

MDV: Some people refer to Hmong in Laos as a hilltribe as its one of the many ethnic groups in Laos and because they lived mostly in the highlands. I don’t often use “tribe” to refer to Hmong people, but the clan structure does exist. Every Hmong person belongs to a clan and I’m part of the Vang clan. Hmong has largely been an oral culture, but we do have a writing system based on the Roman alphabet and that was developed by missionaries in the 1950s.

FR: Do you run into other Vangs?

MDV: Being from Fresno, which has a large Hmong community, I run into Vangs all the time.

FR: What can you tell me about the long-ago Hmong? Traditions, dress,

work life?

MDV: The traditional clothing that Hmong wore back then on a daily basis reflected their clan and regional affiliations. These various affiliations also determined what dialect a Hmong person might have spoken. From what my parents shared with me, daily life revolved around farming and agricultural labor. You’d trek for hours to get to your family’s farm, labor all day, and then trek home.

FR: What time period?

MDV: In the forties, the fifties. Even prior to that, Hmong people have always been rooted in agricultural and farming practices, including when they lived in southwestern China. After ongoing persecution and wars with the Chinese, many Hmong fled into parts of Laos and Vietnam. It’s disheartening to think Hmong people have a history of being on the run as exiles having endured persecution and war. Ending up in Laos and falling into the Secret War was just another chapter in that history.

FR: There’s an image that sticks with me, that will always stay with me when I think of your books, and I don’t remember which book it’s in, but it’s an image of your grandfather. Actually, there are two images of him that stay with me. One is in the poem where he was longing to return to Laos to be buried by a different river and mountain, when he was actually by a river and mountain in California. He was dying and he wanted to die by the river and mountain in Laos. And also, that moment when he brings a particular flower with him out of Laos to wherever his new home would be. I don’t think he was able to keep it alive, right?

MDV: You’re referring to “Your Mountain Lies Down With You.” It’s a poem in Afterland, and you’re right about those images.

Your Mountain Lies Down with You

Mourn the poppies, the mangosteen and dragonfruit.

But you come as a refugee, an exile, a body seeking mountains

meaning the same in translation.

Here they are.

Place your palms on the grasslands. Feel the foothills rise

with gray pine and blue oak.

Here, rest not by the lotus of your old country but with

carpenterias and fiddlenecks of spring.

These woodlands may be unfamiliar, their sequoias thicker

than bamboo, and the rains unable to assemble monsoons.

Still, look out to the distance from where you lie.

You will see Mount Whitney is as beautiful as Phou Bia.

The moon is sharp enough to cut your ear as the one from your village.

And notice how these budding magnolias gesture

like the petals on a dok champa.

Is that the jungle flower you plucked when you fled, the one you cradled

all the way to the ghettos of St. Paul where you first settled?

You cried every time you saw its picture.

Grandfather, you are not buried in the green mountains of Laos

but here in the Tollhouse hills, earth and heaven to oak gods.

Your highlands have come home,

and now you finally sleep.

MDV: I remember writing that poem and thinking about Hmong elders who grieve to return to be buried there where they were born. Hmong elders have a deep sense of affinity to the land of their birth as it’s also where their placenta is literally buried. Hmong believe that when you die, your spirit must return to your birth land to find and retrieve your placenta as part of your journey back to the ancestors. Spiritually, your placenta is considered your finest coat or most prized piece of garment. In the poem, I think about elders who long to be buried in the homeland. The best we could do in the case of my grandfather was bury him in the foothills near Fresno which look out to the Sierra Nevada mountains.

FR: Were you close to your grandfather?

MDV: He died when I was young, but I remember him as a child and have fond memories of him being at home with us. He was a very stern grandfather, and he was also the one who pierced my ears when I was little using a needle and thread.

FR: How old were you when he pierced your ears?

MDV: I was probably four or five.

FR: So the piercing of the ears is something that comes early for little Hmong girls. The poem about the piercing of the ears is in Primordial, right?

MDV: Yes, it’s in Primordial in the long sequence called “Origins.”

~

FR: There was a line that I loved: how your father hides in your steps. The idea of hiding also calls to the Saola, an animal who willfully hides from humans. Finally, we’ve come to the Saola, who hides, and who serves as a haunting symbol throughout the book. Your father is still with us, right?

MDV: Yes, he is.

FR: Is he in Fresno?

MDV: Both of my parents are in Fresno, and I’m lucky to still have them in my life. They arrived in this country as refugees and we were a huge multigenerational household. My paternal grandmother lived with us along with my paternal uncle for a time. Both of my parents have been supportive of my writing. For them, it’s not so much about needing to read my books and grasp my work but an awareness that I am writing about the Hmong experience.

FR: Have you translated your poems into Hmong?

MDV: I haven’t translated any of my poems into Hmong, but if I did, I imagine it would be both interesting and challenging.

FR: I believe that so much of who people are is embedded in their language and the way they speak their language.

If you listened to my mother’s people, children of immigrants who lived and farmed in East Tennessee and North Carolina, the way they talk, their accents and intonations, their syntax and particular slang, it would give you a sense of who they are at some deeper level. It’s hard to explain, it’s almost beyond language, and that may be part of why some people call poetry a kind of singing. Every language has it’s own music.

MDV: There’s a poem in Afterland that utilizes Hmong words to demonstrate the tonality of the language and how the simple change of tone changes the meaning of the word.

Mother of People without Script

You swear the twin spirits

taught you to write.

At night, you climbed

the leaves to hear the gods.

Catch in the throat. Hollow breath.

Paj is not pam is not pab.

Blossom is not blanket is not help.

Ntug is not ntuj is not ntub.

Edge is not sky is not wet.

On sheet of bamboo

with indigo branch.

To txiav is not the txias.

To scissor is not the cold.

The obsidian mask

will make its own sleep,

leave behind the silver

your body won’t shed.

Now you are Niam Ntawv

who was once a young farmer

scrawling in secret toward

the triggering day.

When they could take no more,

when all that you had was given,

you lined your grave with paper.

FR: Tell me about Saola. What do you want to say about Saola?

Of course you’ve said it all in a whole book!

MDV: I’ve thought about Saola for a long time. Saola is a highly rare and critically endangered animal endemic to the Annamite mountains between Laos and Vietnam. It looks like an antelope but it’s actually a relative of wild cattle. Conservationists estimate there are probably fewer than one hundred still alive, if any at all.

I first learned about Saola when I was young, maybe around middle school or early high school. I heard my mom mention something about an animal with horns back in the homeland, and then many years later, I joined the Hmong American Writers Circle, and someone in the group mentioned Saola. It re-activated for me those early memories of hearing about this mysterious animal with horns.

I find myself coming back to Saola as a grounding force in my work. I think about its connection to the war and a landscape that has been ravaged by bombs and chemical warfare. How much of this animal is also a refugee? I don’t want to turn Saola into a metaphor because this animal is a living, breathing species, but I’ve also thought about what its existence and survival means on a figurative level. In some ways, it’s a refugee as well. It’s elusive, it runs and hides, and it has retreated further into the jungle in order to survive.

FR: I have read that Saola has been on the earth for thousands and thousands of years, and that when the West discovered its existence in 1992, it was heralded as a new animal.

MDV: Saola were found to have unique maxillary glands on the face. It was unusual and unlike anything biologists had seen before, and thus it was placed into a genus of its own where it is the only known member (Pseudoryx). Saola took refuge in the Annamite Mountains, which was considered a refugium, a place where animals and plant life thrived despite drastic climactic shifts like the Ice Age. It feels like Saola came to us from another place and time, gifting us with its primordial energy.

FR: Have you ever seen one?

MDV: I have not seen one and very few people have ever seen one.

FR: Are you sure it exists, or ever did?

MDV: Indeed, I do believe they exist. They’ve been observed in captivity and have been seen in the wild. There are villagers who keep Saola skulls as trophies from their hunts. So yes, they exist.

FR: Have people asked you if you are going to go and search for Saola.

MDV: That is part of the conundrum, right? For me to go seek out Saola could decrease its chances of survival. I leave that to the conservationists and wildlife experts.

FR: Wasn’t there a whole mythology around the snow leopard, and that nobody had ever seen one, but we knew it existed and then somebody found one…Am I crazy or did that happen?

MDV: There might have been. The snow leopard also faces threats, and I believe is listed as vulnerable. Again, similar to Saola, they’re elusive animals. They prefer isolation from humans. Elusive animals are either way up in the mountains where you can’t get to them or they’re too deep in the forest. They live in great secrecy. The more we hunt and seek them out, the more risk they face.

FR: Unicorn comes into the picture too when thinking about Saola. I read that when they turn sideways their two horns look like one horn coming out of the forehead.

MDV: I think it was the writer William DeBuys who mentioned that in his book about Saola. Saola has been coined the “Asian Unicorn” and I say that in quotes. The idea of an animal with horns that is hard to find and capture makes people automatically think of a unicorn.

FR: I did read somewhere, it must have been in Primordial, that when they’re caged they die, and that the only ones that have been caged and lived are the ones that were released immediately.

MDV: Yes, and in the case of the Saola that was caged and observed by a biologist, it died of malnutrition. It was also a pregnant Saola in its second trimester. I’ve read that the fetus has been preserved in formaldehyde somewhere in a laboratory and is the only fully-intact Saola specimen we have in existence. I wrote the poem “Tame External Features Come Birthing Endangered in a Cage” about this particular case.

~

I Arrive to Saola by Way of War

I leave the midnight to find your beginning

by way of a village weathering into ruin,

by means of men coerced into combat

by way of an empire shepherding the work

of death. I am here in California and you are

there in the Annamites. I seek you by way

of retreat, refugees fleeing a line of fire

by way of shattered twilight. High grasses

hide limbs near a cavernous sigh in the ground

by way of bombs encroaching on a footstep.

I reach the return of a people plunged into

warfare by way of proxy grab, by means of

American weapons flowing colonizer veins.

I ask you by way of foreshadows, damage

to your life is eventual damage to mine.

The torn sky in yours will rupture the bedrock

in mine. I walk the hours inside my arms to

swaddle questions by way of despair:

how does an evacuee, what of continents

apart, how do politicians away, where alongside

allies, when poaching and abandonment.

In you, a war I never encountered so much

but to be cursed. You bring me to stone dreams

of Hmong wandering foothills outside Fresno

by way of a mountain from an omitted past.

In you, cognizance of exile, shrapnel from an

American war. In you, a sequestered landscape

buried in a world searching for water

by way of every human in the conclusion

of our days. Something in you fallen diaphanous.

Something in you departed and stolen.

~

FR: One of the things that I felt through all three books, running underneath the poems, was this deep haunting sorrow.

In my own experience, it reminds me of 9/11. The closer people were to the event, the more it affected them. For the voice of these poems, that voice is right on it, or in it, or enmeshed in the experiences of the Hmong. Those are the speaker’s roots. Did you ever find yourself writing through tears?

MDV: I think you’re right to observe the underlying sentiments of grief and pain in the work, but also rage, too. I’ve written so much about being Hmong and about the war that I often wonder how to write about something else that doesn’t end up being reduced down to the war, always the war. I return to it because I don’t think the landscape has fully made space for this narrative, for my narrative. With each book I’ve written, I’ve felt compelled to channel through me something that is Hmong. The stakes feel higher for me, too, as a Hmong writer because so much remains unsaid and unwritten. I have often felt as though we didn’t have the chance to speak or write on our own terms. And I’m certainly not speaking for all Hmong, I speak for myself

FR: Is there any other Hmong writer who is writing about the Hmong people and the experience of being Hmong in the world right now?

MDV: There’s the Hmong writer and memoirist Kao Kalia Yang who is a good friend and whose work has been deeply impactful. It’s been helpful to be in conversation with her. I know a good number of other Hmong writers, too, from poets to prose writers, along with Hmong writers pursuing MFA degrees. Together, I think we are creating a new discourse to facilitate the development and future of Hmong literature while continuing to work through the underlying grief that has shaped our collective history.

FR: When you were a kid, your parents were closer to the original grief than you were because you were born here

MDV: I was born about the time my parents resettled here in this country. If they had stayed in the refugee camp another six months to a year, then I would have been born in Thailand. I was born on the cusp between worlds.

FR: Maybe you and your work are a kind of bridge between the old ways and modernity.

MDV: I do often find myself in a place where I have to try and balance both perspectives. There’s an openness in me that wants to hear the elders out while trying to figure out how the old ways might resonate in the modern world.

~

FR: Influences. I heard you read at Hedgebrook when we were there together years ago, and then you went to Columbia and studied with Lucie Brock-Broido?

MDV: I did.

FR: My impression is that your writing transformed while you were at Columbia, right?

MDV: I think it did. Being in an environment where I felt creatively challenged activated something new in my writing. I had the chance to study with Lucie Brock-Broido which was eye-opening. I learned to give myself permission to do things in my work that unsettled me, and the experience altogether pushed me to explore my relationship to language.

FR: What is your relationship to language?

MDV: Complicated. Always. English is not my first language. I’m learning about the ways that my own language, the Hmong language, echoes in other languages or sounds I hear, such as in the syllabics and cadences of English, for example.

FR: I didn’t realize that English is not your first language.

MDV: Hmong is my first language.

FR: When you say that, do you mean that when you were little, all you heard was Hmong?

MDV: Yes.

FR: When I was reading Afterland, my real introduction to your poetry, it would never have occurred to me that English is not your first language. Pages and pages of gorgeous lyric poetry and word juxtapositions I’d never seen before.

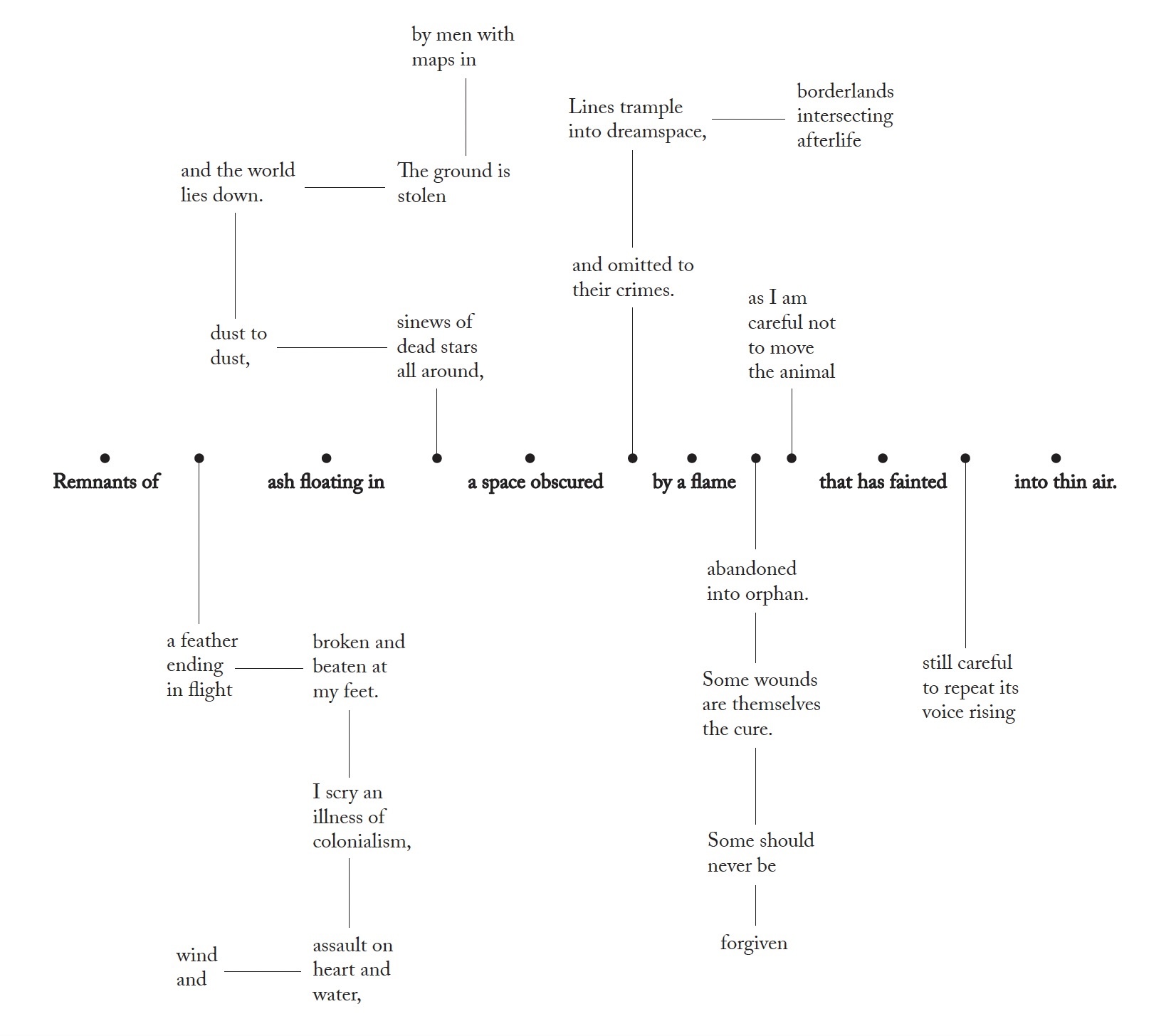

This is reminding me of the form you used in a few poems in Primordial that were constructed on the page almost like a diagram of a sentence, or a family tree with a through line, and dots. A kind of puzzle.

MDV: These are the “Node” poems which are a series of visual poems.

FR: Like, Node: When in the end, and Node: Make your stand

MDV: These pieces were my attempt to rethink the poetic line. Poems are often built or assembled line by line and my interest with the node pieces was to explore how I might disassemble or disembody a poem, but still maintain its infrastructure, its syntax, its grammatical construction. In each node, I was trying to weave a throughline that links to and draws from other lines and phrases. I was attempting to examine how I might connect language above and below, inside and out of, in a visual manner.

FR: Was it partly an intuitive process, deciding what to put above and below the line?

MDV: It was part trial and error and perhaps part intuition. I created many iterations before arriving at the node structure. I was thinking about spacing and visual composition, trying to assess how phrases function in relationship to other phrases based on their position. I’ve even thought about how some of the literal lines function as breath marks indicating pauses and their duration.

FR: Did you invent that form?

MDV: I imagine other poets have done something similar.

FR: I’ve never seen that type of form anywhere else, but I guess it gets down to who you’re reading.

MDV: I think Mary Szybist does something similar with sentence diagramming. In my case, I was thinking more about how to disembody the lines while keeping the poem intact and creating language within language.

~

FR: You love teaching.

MDV: I’ve been teaching for over a decade. I think teaching makes you a better poet, at least for me it has. You’re learning alongside your students, growing your craft as they grow their craft. I find that I get better as a poet when I’m also pushing myself to think about the many ways I can teach it. It’s not really even teaching, it’s sharing and being in community with people who are also excited about poetry and who are emanating an openness to learning about it.

FR: So you only teach in MFA Programs and you’re working with students who want to be poets?

MDV: I teach undergraduate classes, too. Sometimes it is a beginning class, other times it might be an advanced writing workshop. A lot of students come into poetry remembering the anxieties they might have felt about it in high school. For me, it’s about trying to give them a different lens, a new appreciation for it. That moment of re-introduction into poetry is so important.

FR: When did you realize you were a writer? Was it always poetry?

MDV: I don’t know when I had that moment of realization. I still wonder sometimes. But during my MFA was when I found myself doing the practice and work of poetry, even if I didn’t feel like a poet yet. The more I studied and wrote, the more I felt the practice becoming a part of who I was.

When I started publishing individual poems, and much later on when my first book came out, maybe that’s when I felt more affinity with the label “poet.” I was at that point doing the work of poetry, contributing to poetry, and engaging in the discourse of poetry.

FR: Were you writing when you were a child? Did you keep a diary?

MDV: Yes, I did. I started writing cheesy love and friendship poems when I was probably ten or eleven years old. I also loved my English classes in high school. I had a wonderful teacher who helped me develop an appreciation for poetry, and we read Dickinson, Whitman, Frost, Poe, along with other American poets. Dickinson always puzzled me but now I find myself returning to her work to help me think through my own craft and approaches to syntax, sound, punctuation, etc. Maybe she is a creative spirit guide. I’d like to think I am channeling her sometimes.

FR: You were born in Fresno, and that’s the home of Larry Levis.

MDV: Yes, and you introduced me to Larry Levis’ work at Hedgebrook. That was so long ago. I remember you let me borrow Winter Stars. Since then, I’ve been an admirer of his work.

~

FR: The whole idea of fitting in and belonging…Do you have the feeling of belonging now in your life? As a small child, were you going to school with kids from all different backgrounds? Or were you in a Hmong school? The whole thing of being on the run, refugees, never belonging, not being valued…have you overcome all that? From your ancestry, that sense of never being truly home?

MDV: I attended public schools in Fresno and was exposed to many cultures and communities. Throughout my schooling, I had a lot of Hmong friends, too, children of refugees growing up in the eighties alongside me, and there was definitely a sense of us being very much on the outside. What I’ve realized is that you get to a point where you are so far on the outside that all you can do is create your own sense of belonging. You find ways to create belonging that is meaningful to you, that makes sense to you and that is on your own terms. When I finally learned about the war and how and why my parents became refugees and where I fit into the complicated history of this country, I was able to come to terms with the fact that I will never quite belong here. I stopped begging my way into a false belonging and instead helped create a new sense of belonging with other Hmong writers. I feel my place in poetry and on the page now more than before. Poetry is home and every poem I write gives me a chance to belong and fit in somewhere of my own choosing and making.

~

Credits

“Mother of People without Script” Afterland (Graywolf Press, 2017)

“Your Mountain Lies Down with You” Afterland (Graywolf Press, 2017)

“Node: Remnants of ash” Primordial (Graywolf Press, 2025)

“I Arrive to Saola by Way of War” Primordial (Graywolf Press, 2025)