CONSCIOUSNESS RAISED

“This is a test to determine if you have consciousness,” Franny Choi writes in Soft Science. Clearly referencing the 1950’s Turing Test that evaluates artificial intelligence, Choi reappropriates that line of inquiry to reconsider the way that otherness is constructed in opposition to autonomy.

The book’s epigraph from cyber-feminist Donna Haraway (author of The Cyborg Manifesto) is precisely on the nose, referencing an awareness of a “historically constructed body.” And it is a quest for the poet, not a problem that finds a solution. As much as she engages with technology, even while having webcam sex with strangers she always posits herself as outsider, forming a beautifully uncomfortable tension between human and machine.

Or sometimes the outsiderness emerges within the narrator’s own body, lending a candid confessionalism to the poems. “On the Night of the Election” describes drunkenly masturbating in a hotel room as the election results come in, shock alienating her from herself so that her “labia were on the other side of a glass door” and her “clit that night was playing the part of another wall.” The poem conjures heartrending empathy and memory of all the times we’ve tried to seize humanity from despair. But is also points to another way in which the speaker is estranged from herself.

That estrangement manifests often via cyborgs, bots, and all manner of virtual reality, screens for a literal projection of the self. But just as often, the estrangement is bound with more old-fashioned self-loathing: “One night I drank until my body was a claw machine—clumsy, animatronic,” Choi writes in “It’s All Fun and Games Until Someone Gains Consciousness.”

“By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs,” writes Haraway. But for Choi, humans have always been cyborgs, have always been Othered, have always been constructed and construed from the outside.

In “A Brief History of Cyborgs,” Choi writes: “Here, in a seed, is a cyborg: A bleeding girl, dragging a knife through the sand. / An imaginary girl who dreams of becoming trash.” These lines offer so much to unpack—the idea that a cyborg generates organically as a seed and then manifests as forms of femininity. The female pain of the bleeding girl interfaces with the image of dragging a knife through sand, a gently surreal image that’d be at home in a Maya Deren movie or Francesca Woodman photograph. This girl, real and bloody, is also the imaginary girl who dreams of becoming trash, whether it’s a fantasy of becoming a cyborg destined for a heap recycled metal or the disposable face of a woman on Chatroulette.

Chatroulette, a service providing video chat with strangers worldwide, lends its name to a sonnet crown in Soft Science. “To see, to come, I brought myself online. / O dirty church. O two-way periscope, / refectory for Earth’s most skin-starved cocks,” the first poem opens. As much as Choi crystallizes the seediness of these encounters, she also captures the loneliness for real human interaction that underpin the virtual encounters. That loneliness is the speaker’s own, the self-loathing, the quest for approval: “I am the kind of girl who looks for men / to wipe away her face.” In the following lines, she compares herself to a trough for ants, a dirty plate, chicken skin distending. When she writes of ending as a “smear of gut and shell / against the bedroom wall, crushed by a thumb / belonging to a man,” the violence presents a plurality of interpretation. Clearly, the narrator seeks anonymity, self-erasure in these encounters, but then also must deal with the threat of sexual violence. “Don’t worry. That’s not how I go,” she reassures, her referencing to going in direct contrast to her mission “to see, to come.”

Even as Choi writes about all the conflicting emotions in virtual sexual encounters such as these, it’s refreshing to see that she does it without shame or tawdriness. She manages to be frank and eloquent at the same time about her purpose, about her love of attention and fear of disappearing into her own image. For any poet, especially a female poet, to possess the courage for this level of craft and candor, is refreshing.

Soft Science is a thrilling collection, only flawed slightly by its overreach. Between the Turing series, the “Chatroulette” sonnet corona, and a series of poems about the names of the full moons, there are so many big projects that the massive, overarching project itself can get lost. The moon poems, “Perihelion: A History of Touch” seem out of place linguistically and thematically, being infused with more lyric nostalgia than the rest of the book.

Choi’s references to artificial intelligence and virtual interaction are comprehensive, ranging from Turing’s work to the 2001 chatbot Smarter Child to Chatroulette. Yet, the most apt metaphor for Choi’s experience is Snapchat, where users send images that disappear quickly. This way, it’s easy to send a real image of yourself to a stranger in order to have a virtual sexual encounter in which you touch your own, real body–only for your image to disappear altogether. This is a test to determine if you have consciousness.

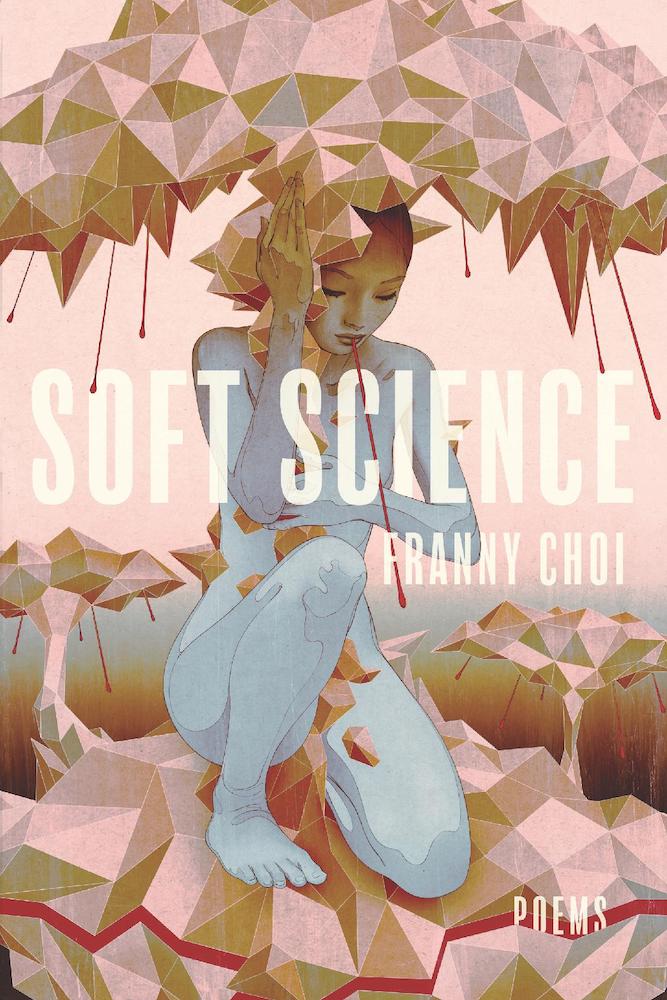

Soft Science

Franny Choi

Alice James Books

$16.95 paperback, 100 pp.

April 2019