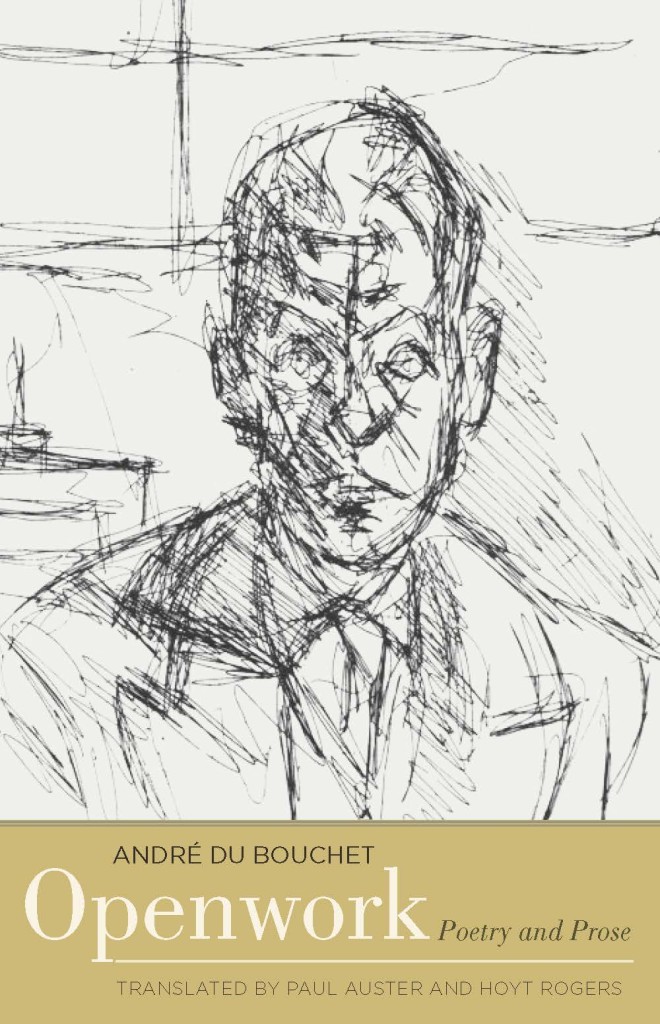

“Excerpted from Openwork: Poetry and Prose by André du Bouchet, selected, translated, and presented by Paul Auster and Hoyt Rogers. Reprinted with the permission of Yale University Press.”

APPEARING OCTOBER 2014

IN THE MARGELLOS SERIES

OF THE YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS

. . . this irreducible sign―deutungslos―

. . . a word beyond grasping, Cassandra’s

word, a word from which no lesson is to

be drawn, a word, each time, and every

time, spoken to say nothing . . .

Hölderlin aujourd’hui

(lecture delivered March 1970 in Stuttgart to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Hölderlin’s birth)

(this joy . . . that is born of nothing . . .)

Qui n’est pas tourne vers nous (1972)

Born of the deepest silences, and condemned to life without hope of life (I found myself / free / and without hope), the poetry of André du Bouchet stands, in the end, as an act of survival. Beginning with nothing, and ending with nothing but the truth of its own struggle, du Bouchet’s work is the record of an obsessive, wholly ruthless attempt to gain access to the self. It is a project filled with uncertainty, silence, and resistance, and there is no contemporary poetry, perhaps, that lends itself more reluctantly to gloss. To read du Bouchet is to undergo a process of dislocation: here, we discover, is not here, and the body, even the physical presence within the poems, is no longer in possession of itself―but moving, as if into the distance, where it seeks to find itself against the inevitability of its own disappearance ( . . . and the silence that claims us, like a vast field.) “Here” is the limit we come to. To be in the poem, from this moment on, is to be nowhere.

A body in space. And the poem, as self-evident as this body. In space: that is to say, this void, this nowhere between sky and earth, discovered anew with each step that it taken. For wherever we are, the world is not. And wherever we go, we find ourselves moving in advance of ourselves―as if where the world would be. The distance, which allows the world to appear, is also that which separates us from the world, and though the body will endlessly move through this space, as if in the hope of abolishing it, the process begins anew with each step taken. We move toward an infinitely receding point, a destination that can never be reached, and in the end, this going, in itself, will become a goal, so that the mere fact of moving onward will be a way of being in the world, even as the world remains beyond us. There is no hope in this, but neither is there despair. For what du Bouchet manages to maintain, almost uncannily, is a nostalgia for a possible future, even as he knows it will never come to pass. And from this dreadful knowedge, there is nevertheless a kind of joy, a joy . . . that is born of nothing.

Du Bouchet’s work, however, will seem difficult to many readers approaching it for the first time. Stripped of metaphor, almost devoid of imagery, and generated by a syntax of abrupt, paratactic brevity, his poems have done away with nearly all the props that students of poetry are taught to look for―the very difficulties that poetry has always seemed to rely on―and this sudden opening of distances, in spite of the lessons buried in such earlier poets as Hölderlin, Leopardi, and Mallarmé, will seem baffling, even frightening. In the world of French poetry, however, du Bouchet has performed an act of linguistic surgery no less important the one performed by William Carlos Williams in America, and against the rhetorical inflation that is the curse of French writing, his intensely understated poems have all the freshness of natural objects. His work, which was first published in the early fifties, became a model for a whole generation of post-war poets, and there are few young poets in France today who do not show the mark of his influence. What on first or second reading might seem to be an almost fragile sensibility gradually emerges as a vision of the greatest force and purity. For the poems themselves cannot be truly felt until one has penetrated the strength of the silence that lies at their source. It is a silence equal to the strength of any word.

PAUL AUSTER Paris, 1973

An unjustly neglected giant of French literature—and obliquely, of several other literatures as well—André du Bouchet was one of the greatest innovators of twentieth-century letters. Trailblazing poet, maverick philosopher, multifarious critic, trenchant stylist, fearless anthologist, daring editor, prolific diarist, intrepid translator in four languages, tireless explorer of nature and the visual arts, he was an authentic iconoclast who has yet to receive his due, especially in the English-speaking world. This anomaly seems all the more inexplicable, given his dazzling renditions of Shakespeare, Joyce, and Faulkner into French. We should also mention his lifelong attachment to the classic authors of nineteenth-century America, particularly Hawthorne and Melville; and in most of his writings, the elliptical syntax and halting dashes of Dickinson inform every page.

By drawing the attention of the English-language public to du Bouchet’s work, Paul Auster and I hope that our anthology, Openwork—appearing this autumn in the Margellos Series of the Yale University Press—will help to rectify a glaring omission. Though most translators and omnibus anthologists of French verse have understandably tended to focus on du Bouchet’s better-known poetry from the sixties, we have expanded the scope of Openwork to include pieces from the author’s entire trajectory, both “poetry” and “prose.” For du Bouchet, as for many French writers of the last two centuries, these modes of expression are intertwined and often indistinguishable.

Throughout his life, du Bouchet spent a large part of his time in the French countryside, devoting himself to the long walks—first in Normandy and then in the Drôme—which nourished the creation of his notebooks. He often jotted down the entries as he was engaged in his rambles, especially during the decade of the fifties, and they have gradually emerged as signal works in their own right. Accessible yet elusive, veering off in unexpected tangents, they are well represented by the sequences translated here. Once the entire corpus of du Bouchet’s journals appears in print, the more challenging texts he published in his middle and later periods will come into focus as trees fully integral to the understory below.

Despite its seeming abstraction, du Bouchet always grounds his work in primal sensation; but the interplay between reality and trope is far from simplistic. As he often demonstrates, even such a straightforward motif as the mountain that recurs in his poetry can never be fully grasped. We cannot encompass a whole mountain from any vantage point. From high above, we cannot observe the core of the rock below its many surfaces. In a horizontal view, we only register one of the mountain’s many faces. All of these vary as well, according to the vagaries of lighting and weather, or the play of shadows made by clouds.

Such phenomena, both outer and inner, are beautifully limned in one of his archetypal phrases: “But the white rock-face—gilded and glazed by the light that picks it out and sweeps it with dim mountains.” Du Bouchet was a translator of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and he twists the familiar phrase “the mind has mountains” inside out. Not only does he internalize the landscape, he externalizes the mindscape. In nature as in art, the mountain we can see is always a metonym. That is why it is so much like a word: never the thing or the concept itself, a word only points in their direction, before retreating once again into its own inscrutability.

Hoyt Rogers

Venice, 2014

from PART ONE:

EARLY POEMS AND NOTEBOOKS

(translated by Hoyt Rogers)

The Piercing Thorns

(from a notebook of 1951)

The piercing thorns, the clear ice-floes of awareness in the vapid light of day and dreams.

Writing when all we find before us is this mute wall that does not answer. Writing because there is nothing left to say; that’s the moment, the worst moment of all, when we have to say it.

I still find myself in front of myself: I must move on.

It’s the immensity that stops me. The untellable sense of choking on reality that makes me set out again. I start over, I shout behind this wall of words that slowly parts, and will close behind me once more. We wanted to go outside: all we did was enter another room.

Writing this text should come as naturally as breathing. Each time, I have to thrash wildly ahead, as if in freezing water. Which means my usual state is suffocation.

Here are the few surviving phrases from the poem I have forgotten, and that vanished with the sun.

Everything has been said, but we have to repeat it again and again.

The horror of seeing these things arrange themselves into words.

Two forms of poetry: the one that takes shape while the poet says nothing, words made of much silence; and the one that molds its words around the hero.

The sleepwalking earth. The printed air stirred by night.

*

Paying with words. Silence gives only silence.

Every poem is a ripped-off piece of bark that flays the senses. The poem has broken this casing, this wall, which atrophies the senses. Then for an instant we can grasp the earth, grasp reality. Then the open wound heals over. Everything goes deaf again, goes mute and blind.

To take hold of man, as real as nature. A mind blazing without words.

Instead of creating words and sentences, I begin by imagining my silent connection with the world.

Assembling words beforehand makes the task easier, but the poem becomes more cowardly.

Lamentation, invective, and interrogation have been supplanted by the impulse to define. Hardly surprising that poems tend to be more concise.

If we could force nature to speak: all hyperboles spring from that. Pry nature open as we pry open a chest—speechless nature.

Eternal back-and-forth between wide-open texts, redolent with objects that balk at words, and these ten lines as tight as a fist.

We need to hollow out in words, in broad daylight, a space analogous to this room, for example.

Man is the conscious part of reality; man is reality’s head.

Like a Man

[from a notebook dated August 23, 1953]

like a man

in a day without sun

that glows

alive

almost

outside the air

…

what I write bothers me as much as my body

it is a white lamp

always lit

even when its light is useless

and day has come

and for no reason I lose myself in the daylight

but should I insist

I would find my destruction

and I see through this framework

I am not dead

I walk till the end of day

without falling behind

as you have to lift your feet off the ground

for the ground to let go

…

every time we laugh, we get to the bottom of reality

…

Sometimes, I have the joy of discovering that I am far behind what

I have already done.

I hurry up to get ahead again.

…

Romantic:

I cannot keep myself from incarnating what I know

is my illness.

I find my shoulders

like a stone

before my illness

it’s that my truth

my sincerity

is still outside myself

I do not incarnate it

is found instead in my friends

and you

my lost wife

I still see you

like a shattered blade

in the frame of the door

the time of thinking of you

and having seen you disappear

you had become as thin and cutting

as a blade

…

I would like to live

having seen

and seeing

should be enough

to become a country

drawing my worth from a river or a road

to become a field

and the plowshare of that field

so that field will work for me

…

I turn to a blank sheet of paper

in order to find some rest

…

Poetry is the price of an animated reality—the pain of an

animated nature. And undoubtedly, all else failing, this pain

is genuine

the pain of what tears itself apart in order to come alive

that is all I have to do, and that is all I do

poetry—what people love—like the audience, responsive above all

to the cadenza—generally written much later—of the concerto,

itself real, which gives the ground, the irrefutable grounding

from which that cadenza removes itself—such is the influence wielded

by a poetry which in that very influence fades away

I Saw the Train Growing Larger

[from a notebook dated March 12, 1955]

I saw the train growing larger with the land

train Venice—Greece

a growing splinter of star, swollen

half-submerged in the black expanse

and the gathering speed, uncanny under the clouds—on the

slick iron

how everything is interwoven

even though we haven’t yet emerged from the earth—from this

reserved enclosure of air

But whoever sees the air a bit beyond the path, for him the path

is lost.

under the dome of air

Then here, stopped in the dead of night, in the heart

of wool country—

embedded in the fields

—at the edge of the mountains, the fire retreats, dies down

…

we are freed from

and attached to the light

then the cold air detaches us from stone—

the day tearing away from us, issuing from the shattered mountain—

we had still recognized the point where we had to

separate

before the streaming black water

…

from time to time, a foray outside the human, in the headless

Outside the walls—

then again the steam of light, a hand that comes down before evening

—we are encircled by that white breathing,

by a breath, close and cold, that widens us.

by a breath close to the building

here, my god, there’s nothing but this black wave that slowly passes.

The heart, this whirlwind.

The heart—hollowed out.

Wood on the chopping block. The gully’s features, left behind by the torrent.

the air that quickens. Then we enter the fire of several

lost faces again—

at the edge of the dull belt of earth.

I stared the road down.

…

twice I have seen the earth shrink

seen its gaze brush the water’s gaze

what reaches me here has not parted with what is lost

stones, cold and hot, answer each to each

the rock interrupted

by new rock

…

Your face next to me,

earth.

After the cold has welcomed us.

Alone, at night—or for all the nights—your face in

my sky, in my head.

your face with eyes closed

there is, in the dryness, blue water

staring at you

from PART TWO:

POEMS FROM WHERE THE SUN

(translated by Paul Auster)

Where the Sun

Where the sun

― the cold, earthen disc, the black and trodden disc,

where the sun disappeared ― upward, into the air

we shall not inhabit.

Sinking, like the sun, whether we have disappeared ―

the work of the sun ― or again moving on.

Up to us ― rugged road up to the brow.

I ran with the sun that disappeared.

Light, I’ve held my ground.

Up to the air we do not breathe ― up to us.

Tomorrow ― already, like a knot in the day. The

halted wind thunders.

As, under the figure

of the sparse

air, in soils overturned upon it, straw, it, sought by the wind, still ―

Uprooting itself, as I move on ― uprooted from its distances, the new soil,

shot through with light.

Up to this earth inhabited under the step, that dries up ― only under

the step.

Like the look of what I have not seen ―

ahead as well.

Under the step, only, opening up to the day.

The face of water from the glaciers. The face of water standing in the day.

But the earth, as long as I run, is stopped under the wind.

Through the stones of waterless paths. Stones half-way ―

In the day and its dust, with the same step ―

upon us, cold, and breath, as if

hovering.

Through what gives, in the distance, another step ( a burden masking the fire,

the coolness )

The air ― without reaching the soil,

even ― under the step, returns.

Postponement

Alone I inhabit this white

place

where nothing thwarts the wind

if we are what cried

and the cry

that opens this sky

of ice

this white ceiling

we have loved under this ceiling.

I almost see,

in the whiteness of the storm, what will come to pass without me.

I do not diminish. I breathe at the foot of arid light.

If there were not the force

of dust

that severs arms and legs

but only the white

that spills

I would hold the sky

deep rut

with which we turn

and which knocks against the air.

In this light that the sun

abandons, all heat resolved in fire, I ran, nailed to the light

of roads, till the wind buckled under.

Where I split the air,

you have come through with me. I find you in the heat. In the air, even

farther, which uproots itself,

with a single jolt, away from the heat.

The dust lights up. The mountain, frail lamp, appears.

The Light of the Blade

This glacier that creaks

to utter

the cool of earth

without breathing.

Like paper flat against this earth, or a bit above the earth,

like a blade I stop breathing. At night I return to myself, for a

moment, to utter it.

In the place of the tree.

In the light of the stones.

I saw, all along the day, the dark blue rafter that bars

the day rise up to reach us

in the motionless light.

I walk in the gleams of dust that mirror us.

In the short blue

breath

of the clattering air

far from breath

the air trembles and clatters.

from PART THREE:

LATE POEMS

(translated by Hoyt Rogers)

Crete

. . . Byzantium

in this rock

as long as the incarnate

toe

is stubbed.

. . . not wanting to turn the water of waters

to steel.

. . . and

legs dangling

into the moment

this day

has

dug.

. . . world

withdrawn from world

you are

there

like falling water.

. . . your back

to the mountain

without leaning

back on the mountain

as between

me and the world.

. . . you

draw

on having

as though on having

been.

. . . looking

all

the way

through

the open

door.

. . . to leave, then, like the snow. without seeing

without sound.

Painting

after the door, I

am — and open, in what I have opened.

where color

has been just a splinter of color, no doubt it is less

like the color itself than a splinter

through that color, and

since it pricks, it looms coldly in front of the color.

its piercing,

like the door ahead

when it opens, that is what it will project

from the loss of identity.

all the rest of the person

must then follow suit.

the eye and the

hand — in front of us, open an expanse where the

rest of the person

has disappeared.

the impersonal

split apart.

eye touching — like a splinter — the sensitive

point to which you have fled once again.

the future — turning back

on itself, dazzles.

but color is you, if you recognize yourself in

the identity you have lost, yourself like a look that blindly rests

where the blind hand rests.

From a Notebook

something of the thickness

of the wind when it starts to blow steals away from itself.

slate pursued in the vein

of its compression.

thirst

entwined with thirst crosses the barrier.

I have found the mountain only by tearing it out.

may you reach me, snow, a man who quickens his step in the snow — as on scalding ground or tiles.

here I have kept in touch with the cold.

the image, I have sought it at its

root — disappearance.

cold that I have breathed once. that is

only once, though endlessly

begun again.

recurrence,

or a blinking — the thickness.

unless to make it solid,

I do not need to — break the sky

between eyelid

and self.

bushes of lavender, locked-up blue.

It was enough — in order to bury the self-born

image, to lift my head.

as

is the ground where my foot has found room.

the dust that gave blueness

sponged away, the round earth has turned black.

color has broken through.

air that carries

vanished words.

the anvil here, and there, which will speak of distances. air

that bears. vanished anvil.

words — anvil vanished — gone together.

a mudslide — sign of the steep slope.

mountain

shorn of its summit, and on its ledges once again removed

from a useless image.

mountain, the perception of that face

still engaging us

from head to foot.

eminences, flowered

heights where the circular sun has turned around to stake its claim again.

cut to the chase

make no conclusions.

what’s withdrawn from this is the earth we will have crossed.

… an about-face

in the thick of things — where new surfaces are found —

brings me back to myself

where I must end.

Paul Auster is known worldwide for his novels, which have won him numerous awards, as well for his films, memoirs, essays, and poetry. But he is also an authority on French literature and a noted translator from the French. In 1982 he edited The Random House Book of Twentieth-Century French Poetry, and he has published translations of Joubert, Mallarmé, Sartre, Blanchot, Dupin, and many other authors. He did his translations of du Bouchet between 1967 and 1971; they were first published in book form by Living Hand in 1976. He has revised them for Openwork. Paul Auster lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt.

Hoyt Rogers has published his poems, stories, essays, and translations in many books and periodicals. He translates from the French, German, Italian, and Spanish. His translations of Jorge Luis Borges were included in the Viking-Penguin centenary edition of 1999. Farrar, Straus and Giroux published his translation of Yves Bonnefoy’s The Curved Planks in 2006, and his anthology of the poet’s recent work, Second Simplicity, appeared in the Margellos Series at Yale in 2012. In early 2014 his translation of Bonnefoy’s The Digamma was published by Seagull Books. Hoyt Rogers divides his time between the Dominican Republic and Italy.