Geffrey Davis’s “One Wild Word Away” reviewed by P.W. Bridgman

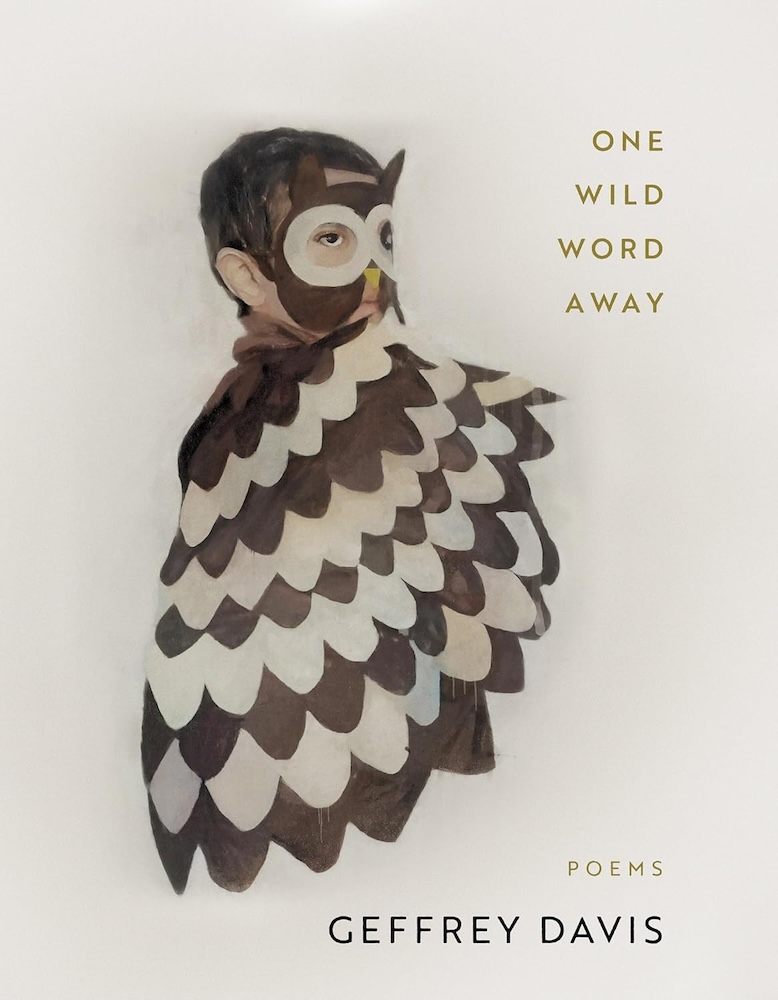

Geffrey Davis, One Wild Word Away.

BOA Editions Ltd., 2024.

Reviewed by P.W. Bridgman

Trauma is “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower” of Geffrey Davis’s poetry (to borrow a line from Dylan Thomas). That being so, this poet finds himself on a crowded and somewhat fraught stage.

Publishing a new collection of literary work that is trauma-themed—even one as deftly executed as One Wild Word Away—is not without risk. The prominence of trauma as an animating force in contemporary literature has divided critics and readers alike. There is ex facie merit in the views expressed on both sides of that debate.

Paul Seghal, writing in the New Yorker, argues provocatively:

The invocation of trauma promises access to some well-guarded bloody chamber; increasingly, though,

we feel as if we have entered a rather generic motel room, with all the signs of heavy turnover.

By contrast, Camonghne Felix contends in a recent Literary Hub article that:

…[I]t makes sense that so many writers and artists make art about trauma, personal and fictionalized—

we write about universal themes because we want to be able to relate to our audiences. Few topics are as

relatable as trauma.

The analysis here is confounded by semantic drift. “Trauma” has become an increasingly elastic notion. That is one of the reasons (it might be said) why writing about trauma is now so relatable to so many. The catastrophic distress that results from comparatively rare events such as the death of a child, or sexual assault, plainly falls within the term’s ambit, but today so too does the emotional disquiet caused by other, less extreme experiences. Whether the expansion of the significations embraced by the word “trauma” is warranted—and what subjects call for trigger warnings—are matters of deeply held and divisive views.

Whatever one’s opinions might be about the breadth of the definition now accorded to the term “trauma,” there can be little doubt that the tumultuous life experience that informs Geffrey Davis’s brilliantly written poetry qualifies for inclusion under the rubric. As the jacket copy for One Wild Word Away notes, Davis’s poems channel “illness, family, [and] loss.” They are “haunted by grief” and confront the speaker’s “generational trauma and the potential loss of a loved one while in the process of raising his own son.” But, just as importantly, Davis’s searing autobiographical poems are also concerned with rebirth; they are propelled aloft by a determined and admirable hope.

At the dead centre of Davis’s life experience, and hence his poetry, lies his father’s intractable addiction to crack cocaine and other illicit drugs—an addiction that “[tore] holes in home once the cravings / had turned his loveliness to smoke.” This white hot, inescapable blight largely defined the crucible into which Davis was born and in which his indomitable spirit, and the writings that have sprung from it, were annealed.

The poems in One Wild Word Away show us that, endlessly held hostage to addiction, the poet and his family endured every kind of insecurity, every kind of indignity. The dull, unrelenting, wearying rhythm of it—the apologies, the promises, the relapses—produced a kind of permanent vertigo for all. Its effects were plainly visible in the fatigue “that framed the youth and / beauty of [Davis’s mother’s] face like a coffin…” (from “Family Portrait with Labor”).

In his worst moments, Davis’s drug-addled father even resorted to pimping his young son to gain money to feed his addiction.

…My father

was a defensive feen who had tried

once or twice to pin my life to his

genesis of drugs, so I knew enough

to rent my body to pain.

When he was raped in a dark basement by his teenaged babysitter, the experience was utterly defeating to the boy:

…Just another

addict’s child who’d learned to stop

asking for mercy. We must have made

a startling two-headed thing: the older boy’s

black curls unfurling from his baseball cap

as he dragged the spade of his tongue

against my naked back…

I was seven or eight, no fathom or use

in my heart for ascending

the stairs, for running the impossible miles back

home across the city or crawling to where

my mother labored to wash

hunger’s reek from her children’s minds.

He must have been fifteen or sixteen, I can recall

the cold flare of the concrete at my chest…

(from “It Must Have Been Summer”)

And yet, the poems in One Wild World Away also confirm—as seems so often (and so inexplicably) to be the case—that a child’s stalwart love and capacity for forgiveness, however severely tested, can seldom be wholly broken by the excesses of an errant and profligately negligent parent. We see this in Davis’s poem “Hush Now”:

…the porchlight tripped by my father’s

addiction remains wired with a hope I have not

shed. Truth be told, the slightest breeze-shift

beyond the heart’s barricade will set me

to picking locks I built in all the miracle shapes

of his leaving. I can still trace my high-pitched

whisper for him to wander back to the pale pickup

he locked me in, a crooked love’s length

from his dealer, as the worst of desire finished

adding him to the dark. Who am I without a father-

sized hole inside my wondering? Who am I

even talking to—by now I have invented more

resurrections than he ever performed

before or after the gravity of his going.

Doggedly persistent love and hope also appear in the first-person poem “Mercy from the Orchard,” where Davis acknowledges his steadfast belief in a “sweetness beyond reason,” saying:

… pity

can comprise a hard pruning. And hope

will leave its own hollow. The moment

I had nothing but violence for that man,

I dreamt an unbroken season of warmth

to cull each cold sorriness he had buried

inside our family’s plot.

By invoking hope and resilience despite the grotesque and protracted mistreatment and neglect it documents, Davis situates his poetry in fraught territory in another way as well. His work enters into the dialectics between abuse and resilience that prove troubled in modern social discourse. Those who have been subjected to harmful colonial practices and racial discrimination, for example, have begun to tire of hearing their communities’ more successful survivors praised for their resilience. Introducing Vinita Srivastava’s podcast series, Don’t Call Me Resilient, the staff at The Conversation write:

We should always celebrate resilience: the human ability to recover or adjust to difficult conditions. But

for many marginalized people, including Black, Indigenous and racialized people, being labelled resilient—

especially by policy-makers—has other implications. The focus on resilience and applauding

people for being resilient makes it too easy for policymakers to avoid looking for real solutions.

There can be little doubt that some readers of the poems in One Wild Word Away will question them from this perspective. Does the writer’s resilience inadvertently make less of his trauma? Has Davis shown too much charity toward his abusive father? Has he let him off too lightly? Is he too little concerned with the remedial interventions that might have spared him, his mother and his siblings some of the misery they suffered? Are his qualified and sometimes-tempered rebukes of the depredations they suffered at his father’s hands insufficiently condemnatory? Are they tacitly enabling?

This reviewer’s own best answer to such inquiries is to ask another question. Does the stubborn hope conveyed in the poems in One Wild Word Away also portend some “real solutions”? What do the poems have to say, for example, about containing familial abuse and neglect and preventing its transmission from generation to generation?

Quite a lot, as it happens. It all seems to come down, in the end, to the poet’s unyielding resolve to find pinpoints of light in pervasive darkness and then later record them in poetry. Recall that Davis tells us in “Hush Now,” that “…the porchlight tripped by my father’s / addiction remains wired with a hope I have not // shed.” When we read in other poems in the book about how he has also dealt with crushing adversity in his adult life, we recognize that it is the persistence against all odds of this unyielding belief that sees him through every seemingly insurmountable challenge—a defiant triumph of the spirit, if you will. One Wild Word Away is the lens through which Davis has permitted us all to witness the marvel of that triumph and, perhaps, learn from it.

That may seem to some to be a naïve, almost Pollyanna-like, perspective to bring to Davis’s powerful, and powerfully dark, poems. But if—to the enduring benefit of his wife, his son and himself (about which more below)—Davis has refused to surrender to hate, cynicism and despair, then these poems testify to, among other things, the possibility that we ourselves, when tested in the future, could refuse to surrender too. Though not a complete cure for trauma, writing poetry has plainly been a “real solution” for Davis. Intergenerational effects propagate and amplify the evil of intrafamilial abuse. It follows that anything capable of disrupting that pattern—even stubborn hope, even the poetry that stubborn hope can engender—surely deserves at least as much attention and applause as does the resilience of those who manage to endure it. While it cannot have been Davis’s express purpose when writing the poems that comprise One Wild Word Away to inoculate others against deep distress and, yes, trauma, his readers’ resilience could nevertheless be a lasting (if unintended) ancillary legacy of the collection.

Of course, one could take other morals from this collection: that, for instance, fate’s random caprices have been unkind to Geffrey Davis. And they have. Quite apart from his harrowing childhood, his poems recall a miscarriage and the deep sense of loss he and his wife experienced in its tragic wake. Then there is his wife’s cancer diagnosis and treatment, and her fragile remission—haunted always by the spectre of the disease’s return. “When” Davis asks, “will our bed sound // less of weeping… // How do I accept // a future for light / with this life not yet saved?”. This quotation comes from “From the Midnight Notebooks,” a long poem that closely examines the chilling uncertainty that lingers despite the uplift of Davis’s wife’s provisional remission from cancer. Later in that poem Davis continues, “…Let us try // any ritual designed // to unsing an early elegy…” And that “us” expands to include the reader.

Though reeling from the effects of these events, Davis and his wife have both nevertheless struggled mightily to fashion a life for their young son that is unscarred and fulfilling. Thus, the moral of One Wild Word Away turns from suffering to compassion, from abuse to tenderness.

Still, the individual sections of the previously mentioned “From The Midnight Notebooks”—each of which begins with the words “Dearly Beloved”—are so poignant, so deeply affecting, that it is almost impossible to read them in one sitting. How can the cascade of fresh traumas that these poems document possibly have been borne by Davis, having been preceded by a childhood of such endless and unspeakable suffering? The answer seems, counterintuitively, to be that the fresh traumas have been confronted without resignation because of the overarching capacity for love, forgiveness and hope with which Davis confronted those annealing early traumas. No one would choose to build character in this way, but this poet shows us that if circumstances require it, resilience-as-tenderness can contribute meaningfully to one’s prospects for survival.

The poem “Crow,” in particular, addresses this possibility. Davis speaks directly to the “child survivor that lives in [him]”. In reverie, they return together to a redbud tree that his younger self believed would never live to flower again. And together they can now marvel at the signs of life that are becoming evident in it.

…Often we were racked

with unthinkable grief, and more sorrow

is surely on its way. But we were blessed

by something, too. And today the soft light,

the coarse tree with its crisp pods, the singing

wind, and this absurd swell of gratitude

for how you outlived the awful wait

that fear can make of longing—which, I’ve come

to assure you, we find bright ways to survive.

None of our love, hope, or ability to forgive are the products of reason alone. Our capacity for reason can, thus, shed only so much light on the source of the wonders that have emerged from the mire in Geffrey Davis’s extraordinary poems.

Even so, readers will not find a single shred of facile, preachy didacticism in Geffrey Davis’s brilliant collection, One Wild Word Away. What they will find there is impossibly dark subject matter transmuted into exquisitely wrought word shapes that, through a rarely seen poetic and spiritual alchemy, will leave them awestruck, uplifted and fortified.

“Sweetness beyond reason” indeed.