DEADPAN DREAMS

On Saturday, April 26, 1952, Ulrich Balslev contacted the Museum of Prehistory in Aarhus, Denmark with news of some interest to that institution. Peat cutters working in nearby Nebelgård Fen had unearthed human remains. The following day, Peter Glob, an archeologist from the museum drove out to the peat bog just south of the village of Grauballe where he found a group of people collected around a dark human head frowning from the newly cut peat. Glob oversaw the careful excavation of the find, Grauballe Man, and its removal for close examination. The body, though tanned by the peat water and contorted by the weight of the overlying strata was remarkably preserved—its nails, hair, and fingerprints intact. The cause of his death (and the apparent reason for his final grimace): his throat had been slit from ear to ear. Sometime early in the fourth century of our era, his naked body was thrown into the fen from which Glob retrieved it and now lies—whole, displaced, and queer—in a glass case at the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus.

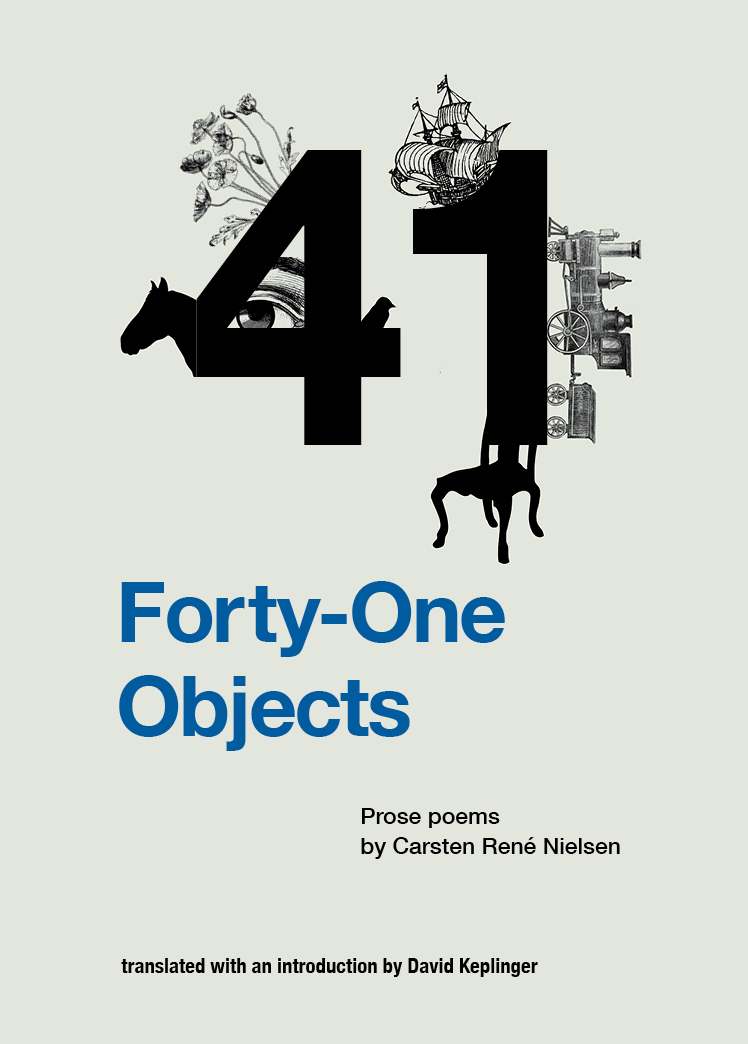

Carsten René Nielsen is himself a resident of Aarhus and Grauballe Man appears about midway through his Forty-One Objects. The poem “Ruler” opens, “Every morning we were given lessons on how to tie knots. The Grauballe Man’s Knot was surely the most difficult.” Many bog people, like Tollund Man, were ritually strangled. But Grauballe Man had no cord around his neck, no evidence of any clothing or objects near him. The “knot” in the poem is a subtle misdirection, a calculated enigma beside many others in this careful and surprising book.

Forty-One Objects is Nielsen’s third book to appear in English. It follows House Inspections and the earlier World Cut Out with Crooked Scissors, itself a selection from three books: Enogfyrre dyr (Forty-One Animals), Clairobscur, and Cirkler (Circles). He has for some two decades devoted himself to the prose poem. That long apprenticeship pays dividends in this latest collection. The poems in Forty-One Objects have a focus and coherence that make them simply more available than much in the earlier books. Here is “Mirror” complete:

Naked, slightly cold and somewhat confused, he stands in the surprisingly dim-lit hereafter together with other recently deceased and looks at an angel, who is giving itself a shave. Even though it has no reflection, it holds up a shaving mirror and lifts up the chin, as it has seen humans do.

The angel apes humans in the very act of observing a reflection, yet the mirrored pairs–human/angel, observer/reflection, life/death–are asymmetric and slightly unsettling. The poem is indicative of the forty other “objects” where a central figure, usually given by the title, is carefully elaborated. Too often poets of surrealist inclination, like Nielsen, produce poems that read like a tedious litany of banal non sequiturs. What’s intended to jog the unconscious is frequently too oblique to be anything but absurd. Nielsen has indulged that penchant in earlier books (“Blow a soap bubble with a mousetrap inside, give him a bump on the head, a haystack served as breakfast in bed.”) but there’s little of that sort of profligacy here. In Forty-One Objects Nielsen pares down. He plays an endgame with fewer pieces on the board and he makes those moves count.

Many of the poems are concerned with the awkward vocation of a poet. In “Self Portrait” a guide is leading a tour through a museum where the poem’s narrator is on display. “‘Here hangs a poet,’ she tells them, ‘he writes poetry,’ and the ladies in her group smile and nod kindly before they move on.” The poem closes with the displayed poet ruminating ambivalently about the guard in the gallery, “I’m sure he hates me. I would too. It’s me, after all, who got him this job.”

That embarrassment is picked up in “Nametag” which begins, “All of my neighbors have gotten new names.” They put on nametags with Zeus, Shakespeare, or Tex Avery while the narrator demurs. He says those around him “see me as a part of the anonymous masses, pretend as if I’m invisible.” But he holds out hope that “one day the fashion will change, and the thing that was once regarded as the most mundane, for a time will be the thing everyone is striving for.” When that happy day arrives, he’ll be asked about his unusual name. “‘This has always been my name, I don’t even have a nametag,’ I’ll answer, knowing full well that no one will believe me.”

All three of Nielsen’s English titles have come into the language via David Keplinger’s dutiful yet fluid translations. I have a smattering of Norwegian and can grope my way through the Danish (thoughtfully offered on the facing pages in this edition). As is typical among prose poems, these are delivered in a deadpan of short declaratives, not the sort of prose that affords a translator much latitude. But Keplinger’s choices are sound and he avoids awkward diction or crabbed phrasing. And from the way Keplinger has described their working relationship (in his prefatory note to World Cut Out with Crooked Scissors) it appears Nielsen himself has a great deal of input in the process, with Keplinger acting as his English amanuensis. Consequently, we do feel we’re reading Nielsen, not Keplinger.

But why prose? The prose poem is a curious hybrid of song and speech. Though a younger sibling to lineated forms of verse, it has by now a well-established tradition running from Arthur Rimbaud through Francis Ponge, Gertrude Stein, and Max Jacob to more contemporary poets like Russel Edson, Charles Simic, and James Tate. Moreover these little fabulae have roots that run back through the parables of Jesus to Aesop and beyond. Yet for all that history, the form remains the exception to the rule—the poetry that is always qualified as prose.

Let’s set aside the more radical practitioners in prose poetry—Ron Silliman and his New Sentence, Jackson MacLow, Lyn Hejinian, and other of that cast—and focus on those writers who, like Nielsen, use conventional syntax and abide by more or less straightforward rules of discourse.

What then is it about prose? We approach a block of prose with a different set of expectations than a poem broken into lines. After all, prosaic is the opposite of poetic. Those justified margins tell us this will be more about the what, less about the how. More descriptive, less figurative. The linguist Roman Jakobson has argued that there are different mechanics at work in poetry and prose. Poetry prefers metaphor and similarity—one thing replaced by another—while prose skews toward metonymy and similarity—one thing associated with another. We are inclined to take the images in prose at face value, knowing they are in the service of the narrative. These are easy generalizations, and exceptions abound, but the distinction points out an advantage prose has over poetry. The unbroken stream of prose, unconstrained by prosody, creates a current that draws us along. Our guard is down. Reading a prose poem comes closer to our lived—or dreamed—experience, and certainly closer to the way we naturally communicate our experiences with others. Nielsen exploits this to good effect.

Consider “Sardine Can”:

Even though I have almost forgotten your face, there are still days I miss you. What a wonderful surprise it was, therefore, to roll back the thin lid on the sardine can and see the sardines, all with your face and dressed in their finest evening gowns, as they lay there row upon row, staring up at me with their big sad eyes.

It’s not simply that he is reminded of the face of a lost love in the eyes of the fish. Nielsen embroiders the figure, and we conjure the striking, rather literal visual image of “row upon row” of tiny women “in their finest evening gowns,” lying in the newly opened can, strange and comic. Nielsen plays up the vaudevillian—shooting elephants in his pajamas and then explaining in detail how those tiny elephants got into his PJs.

Nielsen figures these striking moments against a ground of deceptively unremarkable prose. In “Socks,” the narrator enacts bible stories with sock puppets but the little show flops. Later, realizing what was wrong he envisions a new script. “The arabesques of sentences slowly spin like floodlit mobiles in my skull.” That ornate sentence jostles us out of the narrative–a reminder that this is indeed an artifice, a poem. In “Diary” the narrator describes a diary his father kept in 1963, recording quotidian events—wake-up and bed times, when he showered, what he watched on television. The list goes on until “only one brief mention of the assassination of John F. Kennedy in November ruins the impression of an almost perfect narrative: uninterested, fragmented, incomplete.” Nielsen’s accurate, low-volume descriptions of mundane details draw us in, lull us, and prepare us to be unsettled.

And it is their disarming simplicity that makes these poems so effective. Perhaps the most arresting poem in the book, “8MM Film” begins, “The dead are always filmed in a lighting on the boundary between two seasons.” It’s a pregnant, beautiful figure, and we soon learn that Nielsen intends it in a rather literal sense. He describes in direct language the experience of looking at old home movies. Films in which “on rare occasions, someone moves toward the camera, smiles and talks to it. We see the lips move but hear nothing.” Those of us, like Nielsen, born in the mid-60’s, grew up with these Super 8 movies that captured jerky, silent snatches of family vacations or backyard barbecues. When we see them now, they are populated with the ghosts of loved ones passed, the dead still trying to speak to us. The Danish title is “Smalfilm,” a beautiful word that evokes the incidental and fragmentary qualities of these films that make them—and this poem—so strangely like memory itself.

In his essay “The Uncanny,” Freud noted that when we encounter a fairy tale or other fantastic fiction, we set aside expectations that the story will conform to reality. Bears will talk; witches will fly. None of it surprises. But when a writer brings a story close to life yet deviates from reality in subtle and deliberate ways, the effect is uncanniness. Freud says that writer “tricks us by promising us everyday reality and then going beyond it.” Nielsen’s prose poems shift suddenly from the literal to the figurative—the prosaic to the poetic—jarring us into a state of uncanniness. His Forty-One Objects ignite a sense of wonder. And of awe.

—John Tipton

Forty-One Objects

Carsten René Nielsen

The Bitter Oleander Press

$18 paperback, 104 pp.

February 2019