John Wall Barger

Resurrection Fail.

New York

Spuyten Duyvil

2021.

100 pgs.

Director Michael Mann, when asked why he used digital cameras for his films, said that he preferred the technology because it enabled him to “see into the night.” It was the digital format, Mann insisted, that made the darkness feel most “alive.”

I am often reminded of this quote when reading John Wall Barger, because while there is darkness aplenty in his work, it is always teeming with life. Barger’s recurrent themes include lust, death, mutilation, shame, and suicide, but there is never any hopelessness in his language or approach. Barger is not afraid of the dark, nor is he trying to master it; he is perpetually trying to know it and to bring it alongside him. And as the poetry unfurls through his most recent book, Resurrection Fail, we begin to see that darkness as the poet may see it: a night full of color and depth, always breathing with unmistakable, and at times even joyous, life.

In “The Epic of Senge,” for example, Barger describes transplanting a cat from India to Philadelphia, telling us that once in the city, the animal,

[…] longed for the village life:

fighting cats, hunting rats, walking the roofs

of the huts. He cried his lungs out.

Sleepless, defeated, we opened the door

Senge padded out in triumph.

He walked the sidewalks of West Philly,

manifesting all the lavish beauty

and violence of the village.

While in “Superspreader,” the speaker imagines a plague that behaves like nothing so much as a classic Popeye cartoon:

troubadours in torn waistcoats unpacking

weird barbed instruments, playing quiet music

that makes you erupt in pustules and buboes

or cough blood, suddenly your immune system

crashes, bone marrow fizzling with useless antibodies

which, I learned on House M.D., is called amyloidosis

This approach, curious and respectful and playful all at once, is typical of Barger’s poetry, but there is a drive to this most recent book that sets Resurrection Fail apart from his earlier work. In this collection Barger engages in a much more personal, and at times even personable, confrontation with death.

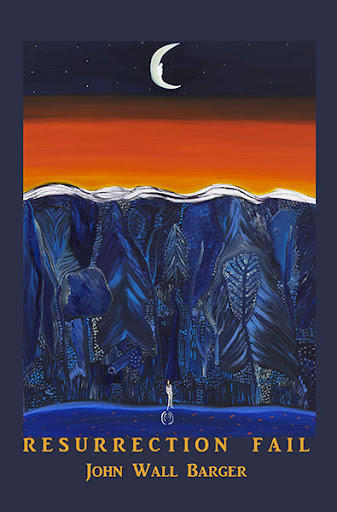

The cover of the book is a mesmerizing reproduction of the painting “End of the Day” by the Canadian artist Matthew Wong, who committed suicide in 2019 at the age of 35. The longest poem here, “At the Barnes Museum on a Cold Fall Afternoon,” is dedicated to Wong, and in it the speaker spends his day wandering the hallways, looking at masters’ work, and thinking of his friend:

before he erased his long arms

and dour face to immerse himself

in nullity, he and I hadn’t talked much,

which is why I can’t explain

his specific grief to you.

The frustration evident in these lines becomes the animating force of the book, and the collection wrestles not just with the question of Wong’s death, but of suicide writ large, a question that acts as the gravitational pull around which the first half of the book spins—at times quickly, as though hoping to break free of the questions Wong’s act demands, and then at other times more slowly, pitching the poems back into the “nullity” that would be the final answer. If Matthew can die, the book seems to be saying, then why can’t we all? And of course we can. In the poem “Resurrection Fail,” we see a scene reminiscent of nothing so much as Wong’s painting from the cover. Barger writes:

then the moon comes,

its kidskin grin,

the Padre Pio cuts

in each of its palms,

while far below

down here

fire rises upwards

water flows downwards

love spirals

outwards

and hour after hour

we carry our dead out of its light

like ants.

Although we may indeed have fire and water and love, what, in the end, is the meaning of our lives in the face of the moon? As Barger’s book moves into its second half, it executes a fascinating inversion, turning backwards, driving the speaker into his own past, and into the resonant and luminous moments of which he is made. Who has he loved? How did he love them? What regrets can he carry and which ones must he lay aside? As these moments are explored anew, lived through again in shame and pain and ecstasy, the poet seems to be asking himself where he lies within those memories. Does he exist in “Polyamory Song,” where he tries after a divorce to keep up with a younger lover, or is he present in “Three Weeks of High School Football,” when he discovers, sitting on his porch and watching a girl and a goat, that he just might be a poet? Is his life the summation of these moments, or is he simply a vehicle that has traveled a road on which these incidents have occurred? At times the poems seek to strip encounters down to their barest physical facts in an effort to most accurately pin their meaning, if meaning there be at all. “1982” begins:

At the Puerta del Sol,

an armless beggar

holds a plastic cup in his teeth.

I drop a coin in it. That sound—

In the course of these revisitations the speaker is forced to come to terms with hard kernels he has long put aside, especially concerning his family. Barger’s fearlessness and tenderness in the renderings of the father are especially potent; ashamed of this man, mystified by him, reluctantly but unavoidably of this man’s body—and even his soul—the poet forces himself to face the specter of the father within his own churning memory. And then he goes further.

[…] He nudges

my door open,

ducks under the chip-up bar.

He is naked,

he is hairy,

my orange Nerf hoop

a halo above him.

For one beat we both stare

ridiculously

at my Tarzan poster.

You are, he begins, fucking

careless, heartless…

I listen.

Barger’s book is full of disarming and honest and delicious surprises that are rare to find, I believe, in poetry this disciplined. And yet, delightful as the collection is piece-by-piece, what makes this book unique is its ambition to work as a larger meditation, moving forward and backward at once to meet a conclusion that is at once wonderful and hilarious and correct. Not a resurrection, certainly, but not a nullity, either. It is a fading, a dimming—an absorption, in fact, by the joyous, riotous, and ever unquiet dark.