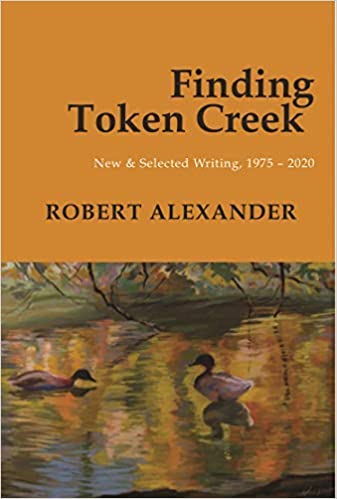

Finding Token Creek: New & Selected Writing, 1975-2020

Robert Alexander

White Pine Press

April 2021

ISBN: 978-1-945680-441

The Sacred and Mundane: A Review of Robert Alexander’s Finding Token Creek

If the title of Robert Alexander’s New and Selected, Finding Token Creek, reminds you at all of Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, that would be apropos. Much as Dillard’s lauded book meditates on the natural world, so too does much of Finding Token Creek. Whereas Tinker Creek is a kind of love letter to Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, Token Creek pays close attention to the natural minutiae of the upper Midwest where we, as readers, are allowed to tag along in the speaker’s canoe, a speaker who seems most at home in quiescence, cataloguing bird species or waiting patiently for the region’s fauna to surprise him.

Finding Token Creek is comprised of prose poems, as Alexander describes them in the essay that opens the collection. “Prose/Poetry” is a chatty, accessible, and well-researched treatise offering one opinion on the genre of prose poetry, and like any piece of writing that seeks to define a genre, you can choose to agree or disagree with the definition. To be fair, Alexander welcomes the reader’s own hermeneutics when he writes, “Each reader…is responsible for accounting for a particular piece of writing in his or her own way; the act of reading defines the text.” With regards to the prose poems within Token, though, his introductory essay clues a reader in insofar as what to expect from the rest of the book. In the penultimate paragraph, Alexander offers, “While prose rises organically from the everyday, poetry with its long tradition of “nightingales and psalms” has about it something transcendent—something, we might say, of the sacred. In this way the prose poem, child of two worlds, serves to bring together, at long last, the sacred and the mundane.”

With regards to this description, we turn to the prose poems in Finding Token Creek, and we encounter what might be described as moments and experiences captured in brief essays, nature logs, pseudo journal entries, or flash fiction stories. We encounter the “I” afloat on his canoe, which is a comforting omnipresence in the collection. In these pieces, it’s fair to align the speaker with Alexander himself. We also encounter pieces written in third person. For example, we are introduced to Ralph, a middle-aged man who finds solace in the natural world while he weathers some of the predictable stressors of living a long life: aging, failing relationships, the frailties of the body. I am reminded, at least tangentially, of Berryman’s Henry from Dreamsongs in that Ralph sounds and looks an awful lot like Robert, and the fictive guise is a thin one. This slipperiness between truth and fiction is aided by the juxtaposition of the first-person narratives nestled up against brief stories of human foibles, third-person takes, and the “Ralph” pieces.

Back again, though, to the meat of Finding Token Creek; The reverence for the natural world—in particular that which exists in the environs of Lake Superior and the upper Midwest—is abundant and beautifully described. In “Ralph Rises Early,” Alexander writes, “Perhaps it’s the angle of the sunlight or the early morning hour, but the combination of morning dew and sunlight reveals, in the bare branches of these tag alder, a myriad of glistening spider webs….Ralph stops paddling. He counts two dozen webs and then stops counting: the webs are like so many god’s-eyes glittering in the branches of the tag alder.” These are the best moments of this book, when we are allowed to tag along on these trips, which never seem to be about getting anywhere, but seem to be about existing within and cataloging ephemera.

Indeed, when Finding Token Creek takes a left turn and I next encounter a story wherein people fumble through their clumsy existence, especially with regards to love and coupling, I look forward to returning again to the lake such that my experience as a reader mirrors the broader sensibility of the book, which is to say that when life gets hard, we go to the lake where “skinning the water’s surface, so clear you can see the sandy lake bottom beneath it, is a thin green layer of ice. In this looking-glass you can see reflected the puffy white clouds motionless in the blue sky, like the depths of a lake you’ve never seen before. Here, at last, is a world you can learn to call your own.” One in which the chaos of the natural order of things somehow makes more sense than the purposeful misguidedness of people failing other people.