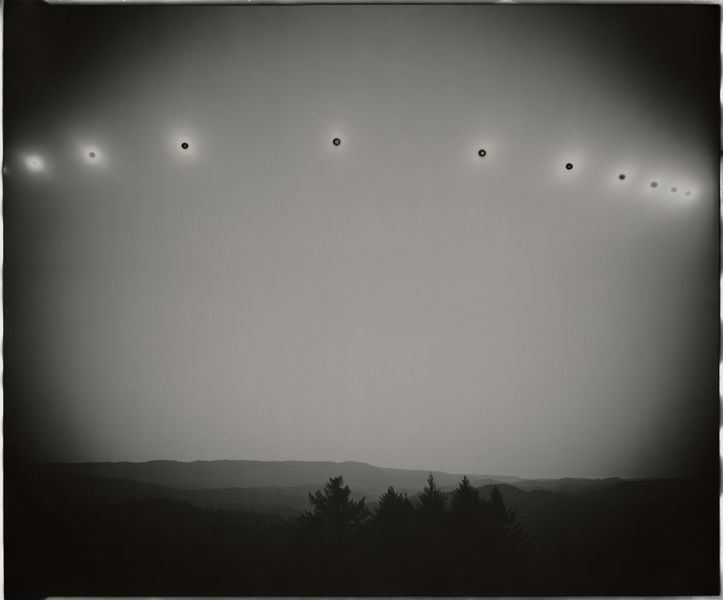

PLUME

Chris McGraw

from the series “Sunburn”

January, 2020

Welcome to Plume Issue #101 —

January: and while here at Plume our starry-eyed celebrations per our 100th issue evanesce, as do those even more sidereal marking the new year’s entrance, it’s good, perhaps, to return to earth and the matters at hand. I speak of the staff shake-ups that take effect this month: in this issue you will see the first fruit of our new Translations Editor, Mihaela Moscaliuc, who rounded up Matthias Göritz’s poem “Throughway” via the good offices of its translator, Mary Jo Bang. As well, you’ll find the initial contribution of Reviews Editors Mark and Chelsea Wagenaar: Chelsea’s look at View from Truth North, by Sara Henning.

I think, like all of us at Plume, you’ll be pleased and look forward to a long and happy partnership with these extraordinary poets and scholars. I can’t think of a better way to begin 2020.

That said, let’s turn now to this month’s “secret poem”, as always, wonderfully introduced by our now not so new but continually surprising staff member, Joseph Campana. This month, it’s the first section of George Oppen’s “Image of the Engine”.

Every day feels faster than the last. So much so I find myself laboring to keep up. With what is not always clear. I’m sure I’m not the only one. Were I a poet of another era I might say “that at my back I hear time’s winged chariot hurrying near.” Maybe it’s mortality. People, increasingly leave, as we will as well. At one time that would have sufficed to answer why we feel we’re hurtling toward some inevitability while, simultaneously, our faculties slow.

At some point, we decided it was not merely an existential state. The term “the Great Acceleration” was coined to refer to a spike in human activity from the mid-twentieth century on. Population, communication, capital, technology, consumption, extraction: everything suddenly on overdrive and with extraordinary benefits and devastating impacts accumulating daily. In a sense, this was everything Filippo Tomasso Marinetti hoped for (and more) when in he penned the “Futurist Manifesto,” published in Italy in 1909 and first translated into English in 1912 for an exhibition of Italian Futurist painters at the Sackville Gallery. “We shall sing,” Marinetti insists in the first of a set of numbered points, “the love of danger, the habit of energy and boldness.” And, indeed, the energy and boldness build:

2. The essential elements of our poetry shall be courage, daring, and rebellion.

3. Literature has hitherto glorified thoughtful immobility, ecstasy, and sleep; we shall extol aggressive movement, feverish insomnia, the double quick step, the somersault, the box on the ear.

I love that poetry seemed central, to Marinetti, to a global, cultural revolution. And certainly, vitality and intensity make for great poetry. But for Marinetti, the “beauty of speed” that proved irresistible, a temptation hurrying on to darker longings: “We wish to glorify War—the only health giver of the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive arm of the Anarchist, the beautiful Ideas that kill, the contempt for woman.” That war gives health and that women must be held in contempt to guarantee a world of exquisite and swift technology are just a few of the nightmares Marinetti was pleased to unleash on the 20th century which itself unleashed hosts of depravities. How happy he might have been to think he could hear the silent digital screams we now feel in an age of exponentially increasing speed.

Marinetti jumped in his fast car to speed away from the culture of slowness Friedrich Nietzsche extolled some decades earlier in a now much-quoted passage:

“I have not been a philologist in vain — perhaps I am one yet: a teacher of slow reading. I even come to write slowly. At present it is not only my habit, but even my taste — a perverted taste, maybe — to write nothing but what will drive to despair every one who is ‘in a hurry.’ For philology is that venerable art which exacts from its followers one thing above all — to step to one side, to leave themselves spare moments, to grow silent, to become slow — the leisurely art of the goldsmith applied to language: an art which must carry out slow, fine work, and attains nothing if not lento.

Hence the injunction to “read well, that is, slowly, profoundly, attentively, prudently, with inner thoughts, with the mental doors ajar, with delicate fingers and eyes.”

Clearly, despite my feeling of ever-growing haste, I have slowly unfurled this column as I try to think about what it means to read and write slowly in an age accelerating away from the age of acceleration. Of course, speed can be genuinely and not destructively exhilarating. So as I write, close to my deadline, on the eve of a holiday, I wanted to share a poem—a piece of one, anyway—that has the intensity of speed and yet that forces us to slow down. Speaking of slow reading: I’ve been living with this poem now for over twenty years, still inventorying its wonders and wondering if I understand it at all. The poem is George Oppen’s “Image of the Engine” and what I want to read slowly with you is its exquisite first section.

1.

Likely as not a ruined head gasket

Spitting at every power stroke, if not a crank shaft

Bearing knocking at the roots of the thing like a pile-driver:

A machine involved with itself, a concentrated

Hot lump of a machine

Geared in the loose mechanics of the world with the valves jumping

And the heavy frenzy of the pistons. When the thing stops,

Is stopped, with the last slow cough

In the manifold, the flywheel blundering

Against compression, stopping, finally

Stopped, compression leaking

From the idle cylinders will one imagine

Then because he can imagine

That squeezed from the cooling steel

There hovers in that moment, wraith-like and like a plume of steam, an aftermath,

A still and quiet angel of knowledge and of comprehension.

In nearly any context I can, I teach this poem. I want my students to think about how poems generate intensity, how they balance abstraction and generality. I suppose I’m looking for the kinetics of poems as well. Here, we begin in diagnosis. The poem is “The Image of The Engine” and there’s something wrong with the engine. What happens, extraordinarily, over these sixteen lines of exquisitely balanced syntax and lineation? The engine breaks down before our eyes and ears. Knowing that “a ruined head gasket” is the cause cannot explain the captivation of impending collapse. The gerunds— “spitting” “knocking,” and even “bearing” which refers to a part—surge forward while the short, sharp nouns slap back. It’s a “hot lump of a machine” which is to say it’s already dead only the poem can’t quite let go of its delirious motion. To say “when the thing stops” is to see it lurch back to life again “stops, is stopped…finally stopped.” It’s like we’re on a bike rushing down a steep hill and we can hear and feel the bike shuddering to a stop as the brakes try to cease momentum. I am not nor ever will be any more adept at automotive mechanics than turning over the engine of my car, but it’s worth saying that the poem masters a particularity of engines now lost on most of us. My students haven’t always heard of VHS tapes so forget about flywheels.

Caught up, as we are, in the extraordinary breakdown of the engine, we might miss the subtle appearance of the perceiving mind in this poem. Once steam hisses from the engine, the imagination enters simply because we can imagine: we are the creatures of imagination. Only here, the steam of the defunct engine becomes an angel. That’s also what the imagination can do. This is an angel of neither apocalypses nor greeting cards. Before us, something rises “wraith-like and like a plume of steam.” The thing is not the steam because the thing is like steam. Suddenly, this utterly concrete poem lives in a metaphysical world of angels. It’s a machine that breaks so it can work, and the work that it does, the work of the imagination, is to produce “knowledge and comprehension.” These are words so abstract—and doubly abstract together—that I’m sure I’d tell a beginning poet not to pile them up together. And yet here they are. One measure of a great poem is its balance of particularity to abstraction. Here the balance shifts late, and it’s a revelation.

In this holiday season, here’s to hurrying up to slow down. That’s what the ancient Romans wished for when they said festina lente, an oxymoron that signal the need for the intensities of speed to live in harmony with meditative slowness. Oppen’s poem speeds us through a breakdown it languorously depicts. It has the zeal of speed but it accelerates into stillness from which comes wisdom. Here’s to revelations and angels and engine and the great George Oppen from whom I learn every time I read “Image of the Engine.” And here’s to the gifts poetry gives, daily when it stills our minds and speeds our hearts.

Happy holidays!

For biographical information on George Oppen look here

Joseph Campana is a poet, arts critic, and scholar of Renaissance literature. He is the author of three collections of poetry, The Book of Faces (Graywolf, 2005), Natural Selections (Iowa, 2012), which received the Iowa Poetry Prize, and most recently the The Book of Life (Tupelo, 2019). His poetry appears in Slate, Kenyon Review, Poetry, Conjunctions, Guernica, Michigan Quarterly Review, and Colorado Review, while individual poems have won prizes from Prairie Schooner and the Southwest Review. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Houston Arts Alliance, and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. He has reviewed the arts, books, media and culture widely and is the author of dozens of scholarly essays on Renaissance literature and culture as well as a study of poetics The Pain of Reformation: Spenser, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Masculinity (Fordham, 2012). He teaches at Rice University where he is Alan Dugald McKillop Professor of English.

Once more: If you enjoyed Joseph Campana’s piece in this newsletter, and last month’s — and how could you not? — all of the Plume newsletters are now archived under, well, Archives, on our homepage.

What else?

Last month, I noted that Plume Poetry 8 has wrapped, as indeed it has. But, now, a change from our usual schedule. For a number of reasons — logistical, personal, professional — Plume will not attend nor, consequently, have its annual debut reading at AWP. San Antonio is a city I don’t know, and making venue connections has proved to be all but impossible despite our best efforts – and those of others. There have been family issues, too, which have kept me away from the journal, and for that I apologize. But, more than these matters, I confess, worthy as parts of it surely are, over the years I have grown less enamored of the enterprise in general, with its hordes and especially as it relates to – book sales. Or, lack thereof. The return on time and trouble finally has reached a tipping point. I think we’ll do better by scheduling regional readings in the months that follow AWP – which is where you, dear Plume contributors, come in. Before too long, you will receive an email from our publicist, Mary Bisbee-Beek, asking for your help in setting up these smaller events in your area. We have done these readings in the past and have found them much more productive, in sales, than our AWP blowout, though I admit I’ll miss those readings, and particularly the after-get togethers. More on this later. (And it’s quite possible we’ll be at AWP/ Kansas City in 2022, as we have close friends there).

As we continue our Staff highlights, this little gem:

Hélène Cardona’s recent book Birnam Wood (Salmon Poetry, 2018), a translation of her father José Manuel Cardona’s anthology El Bosque de Birnam, won the 2019 Readers’ Favorite Award Gold Medal in Poetry. It was Named Best Translation in the Washington Independent Review of Books and is a World Literature Today Notable Translation of 2018.

It was recently reviewed in Bookaccino, North of Oxford, World Literature Today, Readers’ Favorite, and The Los Angeles Review.

(Almost) penultimately, again a request. As you will note, I try to highlight recent of soon to be published books by Plume contributors at the conclusion of this newsletter. My method for gathering these materials is haphazard, to say the least. Now, I want to rectify that to whatever degree that is possible. So – if you have a new book — or have won some award or grant or other, perhaps send me a quick email – I want to highlight your many wonderful achievements here. And a little PR never hurts, right?

Our cover art this month comes from Chris McCaw: for more on this artist and how this remarkable photograph, one of a series, was produced — calculated long exposures of the sun, made with paper negatives in a custom-made large format camera, forcing the sun to physically burn a trace of its arc into each photograph — try this link to Lens Culture.

And finally, per usual, a few recent/new/forthcoming releases from Plume contributors:

Martha Collins Because What Else Could I Do

Carrie Etter The Weather in Normal

Jane Hirshfield Ledger

Brenda Hillman Extra Hidden Life, among the Days

Carl Phillips Wild is the Wind

Tom Sleigh House of Fact, House of Ruin

That’s it for now – I do hope you enjoy the issue!

Daniel Lawless

Editor, Plume