VOCATION FOR LONGING

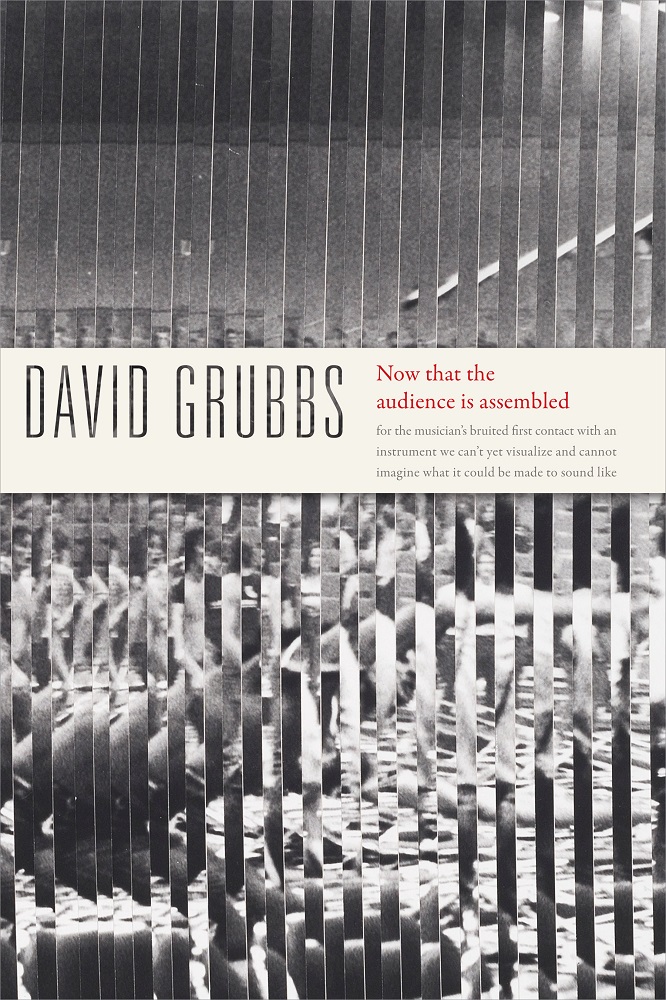

Now that the audience is assembled

David Grubbs

Duke University Press

$74.95 hardcover, $19.95 paperback, 152 pp.

April 2018

Now that the audience is assembled, David Grubbs’ new book of narrative poetry, threads the results of years of practical research in two related fields: sound studies and the performance of experimental music. And I do mean practical; though he has a background in punk and hardcore, Grubbs has worked for much of his life in—what is too simply called—experimental music. He’s made a series of solo guitar records, but he has also worked extremely broadly as a collaborator—most famously in the 90s with Jim O’Rourke in Gastr del Sol and Mayo Thompson in The Red Krayola, but more recently with the poet Susan Howe, with whom he’s made recordings that combine his sound composition with her writing.

Grubbs also teaches at Brooklyn College, and in 2014 published his first academic book—Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording. Taking its title from a quote of John Cage’s, who was pessimistic at best about the use-value of recordings, Grubbs ably investigates the history of recordings of sonic performances that were poorly matched to recording media—think long-form experimental work, extremely quiet minimalist work, or improvisation that was explicit in the fact that it was supposed to be heard live and in the moment. The book was well received, not least because of its legibility. Grubbs is, above all else, an alert writer. In his academic writing, he eschews theoretical mumbo jumbo for careful journalistic description. Here he is defining musique concrète, an important early experimental genre based around a kind of proto-sampling:

Musique concrète began with the basic concept of reversing the polarity of “abstract music.” Music composition

traditionally begins with abstract elements—pitches, scales, compositional forms—and ultimately finds

realization in concrete sound. Musique concrète, by contrast, begins with sounds and their material

representations in recorded form, and creates the possibility for abstract arrangements of these sound objects

in musical compositions.

Grubbs brings this clear spoken prose to his new book, which works on its own or as a sequel to Records Ruin the Landscape. The book is a long narrative poem that describes an overnight performance of experimental music. Though Grubbs attends to line breaks here and there, the book is written as prose poetry, 2 to 3 paragraphs a page. The book intertwines three performances, or three sections of the same performance. This is the beginning of the second:

We’re going to work with gongs.

At the magic word the entire audience awakes and frantically begins to make ready. Each person stands up

and without a word of instruction folds his or her sear and passes it back to the rear of the room, where they

are stacked in neat rows. Everyone is astir. The occupants of the first several rows invade the stage area… A

number of working groups organize themselves, beginning with an informal carpenters’ guild that proposes

to design and construct the structure from which to hang the gongs.

The three performances are: 1) the performing artist investigating and playing with a large pile of trash, 2) the performing artist directing audience members to play gongs and drums in a large Viking ship, and 3) a kind of coda where the performing artist attempts to leave the theater, and then ends up playing the piano in a softly improvised way.

Key to the book are Grubbs’ shifts in tone. Though he’s nominally concerned with describing the work of the performing artist, Grubbs moves in and out of his flat journalistic prose and a stylized, more poetic prose to show how experimental performance works as a series of framed negotiations, first between performer and instrument, then performer and audience, then audience and theater, and on and on. As an example of his less journalistic side, here he is, in a rewriting of the Rifleman’s Creed, describing the relationship between the performing artist and her piano:

This is my instrument. I know where it ends. It will always be my first instrument, and for a time I thought of

it as my one instrument and also as the means of visualizing music. Then I dove into the spaces

between keys and learned what’s not a piano. The piano is neither cello nor bloodcurdling shriek. It includes

neither pitch wheel nor portamento ribbon. It’s not the sonification of data. I know the piano as touch, I turn

to the piano as a machine to amplify touch, a machine to flesh out touch; it presses flesh with, it shakes hands

with the machinery of my arms, hands, and fingertips. To the extent that I am free to be ignorant of what I

do it is because of my fingertips.

It’s a useful technique—it allows Grubbs to foreground his theoretical concerns while still describing a real situation—but he doesn’t quite pull it off. The above is one of the best sections of the book. More often Grubbs’ higher style is less practiced and a bit purple: “mocking footfalls in fictive zero-gravity boots and fake truffling…” The book is closer to ethnography—field notes written in a diaristic flash combined with after-the-fact academic research—than to poetry.

Thankfully, Grubbs seems to know his strengths. He emphasizes his flatter prose, and the book purposefully works exactly like an evening of experimental performance. It’s alternately daring and boring, ethically responsible and totally self-indulgent, open-ended and foreclosed, surprisingly forward thinking and melodramatically conservative, and on and on and on. Unlike other attempts at similar subject matter—most notably Nathaniel Mackey’s long serial prose masterpiece From a Broken Bottle Traces of Perfume Still Emanate…, but also quieter works like Pamela Lu’s Ambient Parking Lot, Grubbs is never quite able to translate the mishaps of performance into interesting writing. One section, where the audience largely falls asleep, has a sleepwalker write I HATE THIS in chalk on the back of the auditorium:

I

Ranks of sleepers convulse, approach the spike in snoring that precedes

eyelids popping open.

HATE

Does anyone really want to see this? The page-turner makes to squelch the interruption but composer and

musician simultaneously restrain him, the both grasping an upper arm and gesturing with an index finger laid

upon closed lips, eyes silently imploring that he not disrupt the incoming message.

THIS

Indeed. Compare this to a moment of conflict in Mackey’s book, when his main character N. is plucked out of the audience and asked to play his bass clarinet without warning:

The opportunity both excited me and gave me cause to be wary. The tenor man was still

deeply into his solo, blowing an insanely beautiful tremor figure which, as did everything else, made his “act”

an almost impossible one to follow. It was then that it occurred to me that the emotional cramp I’d felt in my

throat might very well have been a dowry. I say myself as a “bride” by way of whose wedding what had been

confirmed was—how can I put it?—a vocation for longing. It was nothing less than a calling brought about

in such a way that one nursed a sweet-tooth for complication.

Mackey is a master, and it’s unfair for me to compare Grubbs’ writing to his. But reading the two writers back to back emphasizes a problem Grubbs sets up for himself that he is unable to surpass: he wants his book to work more like a piece of music than a piece of writing.

What do I mean? And why might this be a problem? The key unit of a musical performance is time. While there are certainly many composers who play with time—decreasing or increasing, emphasizing or de-emphasizing its presence to some degree, the performance of music happens in the moment. This, for the most part, is how Grubbs writes—whether in academic or poetic prose, Grubbs’ highest goal is to describe what is happening in the room:

The composer fashions a small battery of molar-sized percussion instruments attached to a curve of bone

that resembles that jaw of a large animal. The page-turner soberly pings and bends and

bows a rusty saw.

Nine gongs hang abandoned.

Now re-read the Mackey quote. Key to Mackey’s writing is that he uses the performative moment to expand time, to give it space, to let it breathe. It isn’t enough to say that N. is having trouble following another performer, Mackey compares the situation to a vocation for longing. This is a basic key to classically good writing, but it’s especially important—to this reviewer—when describing the ephemeral. When Grubbs allows this to happen—as with the Pianoman’s Creed above—the book is a joy to read. But too often Grubbs overwrites to suggest musicality. More experimental writers are able to play with this problem, but Grubbs, though he’s describing experimental music, is decidedly not an experimental writer. This is a rarity in our moment: a narrative poem that simply narrates.

I’m being hard on the book, but that is because there’s so much promise, not only in the recovery of this form, not only Grubbs’ pedigree, but that he’s discovered this form for himself. In his helpful afterword, Grubbs writes about what he wanted to do with the poem:

The musical situation that I found myself eager to describe is a concert of experimental or improvised music.

I realize that doesn’t tell you much. But this initially baggy subject proved self-generating; it became the

opportunity to write about solo performance, free improvisation, text scores, instrument building, time

killing, masochism, performer psychology, audience behavior, audience and performer bad behavior, the all-

night concert, sleeping through a concert, waking up in the midst of a concert, the deskilling and reskilling of

conventionally trained musicians, the curious and occasionally vestigial role of the composer in experimental

music, a lifetime of fraught relations with one’s first instrument, and more.

Though these themes are all touched on in the book, one comes upon the writing of them in gestation. Development is delicious to witness during a concert—one waits to see how a musician transforms a note into a melody into a refrain. It is more difficult to read development in writing—shouldn’t writing already be fixed? Having sat through many experimental music concerts myself, I know how to wait patiently. And I wait patiently for David Grubbs’ next narrative poem.

— Devin King