Odesa Poets Portfolio

Introduction by Ilya Kaminsky

I open the door to the sound of chairs scraping concrete. I am gripping a wine bottle like it’s my first time holding a newborn. Eyes flick as the door shuts behind me, then back to the stage, while I squeeze awkwardly between legs and backpacks. A warm, insistent hand grabs my sleeve and points to a chair. I tap my ear, shake my head, gesture towards front row, and proceed with all the subtlety of an American at a foreign poetry reading. (The fact that I was born and raised here means nothing—I am somehow an American now.)

I inch forward, past an old lady bobbing her head in the corner, her cane propped against knees; past some huddled kids passing a notebook; sidestepping a man whose beard rivals Rasputin’s, clearly you could lose a cat in it. Then, because God’s sense of justice is endless, my foot snags an extension cord, and the wine bottle launches into what it must think is a flight.

“Shit!” is my eloquent contribution to the evening’s poetry.

But suddenly, a woman grabs the bottle with a combination of both hands and a skirt, and a laugh. Then she gets back to her poem, and the room leans in, eager to return to the sound of her voice.

When she’s done, Maya slides into the seat next to me. “Quite a grand entrance,” she types on her phone “You always crash poetry readings with such flair?”

“Nah,” I type back, “only to impress brave Odesans”

“Maya,” she types her name. “You?”

“Ilya,” I type. “I saw you read here last year when—”

Time is a circle in this city. We are always seeing each other read, always introducing ourselves, always in the middle of a sentence. Meanwhile, Rasputin’s beard grabs the mic, and although I my deafness keeps me from hearing the air-raid siren from my front row seat, I see its effect ripple through the room, some people rising, and the screeching of chairs on concrete that my hearing-aids can pick up. Turning around, however, I am surprised to find though that most people stay seated.

The old lady near the back pulls a half-eaten sandwich from her bag, unwrapping it with methodical precision of a bomb disposal expert. Rasputin’s beard reaches for his cane, then seems to think better of it, settling back with a resigned shrug.

Evgenii, our octogenarian host, rises slowly, his pink bald spot quivering like a jellyfish washed ashore. “Shall we take a vote? Who wants to go to the bomb shelter, and who wants another glass of wine?”

Hands rise, in a universal gesture for “more wine, please.” Of course they do.

*

A young couple in the back row link fingers, their free hands lifted high in unison.

I can’t help remembering the most recent interaction with Evgenii, when the Russian tanks first crossed Ukrainian border, a month or so ago. I remember the clock showing 3:17 AM when my fingers moved over the keyboard, telling him I had been glued to the news all night, and if he could please tell me he is okay, please, and what could I do, please, how could I help?

I remember hitting send and hearing the familiar swoosh of the sent message through my hearing aids before I could second-guess myself, before I could delete the message. The man certainly had enough on his plate without my worries.

His reply had come faster than I expected, just as I saw the news update that ballistic bombs had begun to descend on the country.

“Ah, I need nothing.”

Now, a couple of month later, in Odesa, watching him raise his wine glass as air-sirens blared, these five simple words resound.

But not at that moment.

Evgenii, please, I wrote again, there must be something I can do, anything?

His response took longer this time.

“Putins come and go. We are putting together a literary magazine. If you want to help, send poems.”

Maya’s phone lights up, interrupting that months-old memory:

“Stay?” Her eyebrows are a half-raised challenge.

I hesitate, eyes sweeping the room. A boy, barely ten, hunches over his notebook and writes something quickly but so neatly.

Evgenii’s eyes waltz between alertness and near-dozing, like he is trying to decide which reality he prefers.

I nod. Maya types: “Good. The real poetry hasn’t started yet!”

*

When the building shudders, dust drifting down, Evgenii’s bald spot quivers like it’s trying to escape his head.

Then the young boy stands up, his voice clear. The siren is louder now, but we see him say, “Should… should I?”

“Please do,” Maya shouts from our front row, raising her glass. “If they are going to keep bothering us with air-raids, lets give them a soundtrack they won’t forget.”

Another hour passes and just as the reading ends, Oleg steps through the door, his chest heaving and forehead glistening with sweat, a mixture of disappointment and relief in the set of his jaw. Everyone was leaving, so he turned around and minutes later he is reminiscing about the history of “Evening Odesa,” where he is head editor, his commentary punctuated by an occasional wry shrug.

“You should have seen it in the ’90s. We were printing on whatever paper we could find. Sometimes I think the readers were more interested in what they could do with the paper than what was printed on it.”

“But how, Oleg—” Maya interrupts, as we weave between trees on the sidewalk covered with sandbags and anti-tank devices, “how is the paper holding up these days?”

“Holding up? We lost half of our subscribers when—” Oleg pauses.

“When half the city fled?” Maya finishes for him. A violinist hurries past, case bouncing against her back. She collides with a man carrying a crate of apples away from the market. He steadies himself, calls out. She waves without looking back, already late for whatever urgency awaits.

“Reminds me of my submarine days.” Maya says. “Chaos above, calm below.”

I blink. “Submarine days?”

“I remember trying to keep divers breathing through outdated Soviet contraptions while trying to lift a submarine from the bottom of the Black sea.” Maya’s hands are moving as if adjusting an invisible valve. “At the end of the 90s, everything was falling apart, including our gear.”

I try to understand but I don’t, so I picture Maya the poet, grappling with rusting pipes and valves at the bottom of the Black Sea.

Oleg snorts, shaking his head, “For Maya, that was a mundane daily activity.”

Our conversation moves on. Oleg is writing about the refugee center he and I had just visited, I watch a seagull dive for discarded bread. “At the refugee center, kids are climbing all over Isaak Babel statue like he’s a jungle gym.”

A coffee cart appears around the corner, the smell cutting through air towards us. Maya veers towards it, fishing coins from her pocket. “Three,” she tells the vendor, then returns to us. “My treat. So, these kids at the center. Parents awol?”

“Job hunting, apartment searching.” I accept a cup from Maya, heat seeping into my palms.

“Maya! Maya Dimerli!”

A woman in a paint-splattered smock waves from across the street, nearly upending her easel.

Maya smiles. “Elena! Festival prep going okay?”

Elena dodges a cyclist, canvas flapping. “Barely! This poetry-jazz fusion you are planning is giving me gray hairs. It’ll be worth it, right? I was thinking we could—”

“Sorry to interrupt,” Oleg cuts in, “but we’re is in the middle of something important. Maybe catch up later?”

Elena deflates, but nods. “Of course. I’ll call you!”

As she hurries off, Maya turns, “Ol—”

“Please. I just didn’t want to stand here all day while you two jazz out.”

Maya laughs. “The kids,” she prompts, turning back to me, “You were saying?”

“Right. I was thinking they need a distraction. Something to do with themselves in the air raid shelters, instead of just staring at blank walls. Like poetry.”

*

“Poetry?” Oleg snorts, coffee droplets flying. His jaw clenches, then relaxes as he looks at our faces.

Maya’s eyes narrow as she taps her fingers against her thigh. After a moment, she nods slowly. “It’s…it’s not the worst idea I’ve heard”

We pass an abandoned storefront. Through newspaper-covered windows, a single red high-heel overturned.

“So where would this literary masterclass happen?” Oleg asks, rubbing his side.

“I might know a place,” Maya volunteers. “Got a friend at the library”

“The one with the cats?” Oleg asks, he and Maya share a glance. “Why not?” Oleg shrugs. “It’s not like the world can get any crazier”

We round the corner into a wave of grandparents and children spilling from a daycare. A henna-haired woman clutches a little girl’s hand, the child’s other arm wrapped around a one-eyed stuffed elephant. A grandfather in a faded naval cap hoists a boy onto his shoulders, small fingers tangling in gray wisps. Their chatter mingles with the clatter of the approaching tram. In the midst of this chaos, that evening’s conversation turned into a plan, and the plan unlikely as it was (just a couple of hours away, in neighboring Kherson, drones sent by the Russian army hunt civilians daily) became a program where local kids from Odesa schools and refugee kids from all over Ukraine share poems, and write their own.

Here is a poem by Tamara, a ten year old girl:

I have a sore throat,

The doctor will come

And start bossing everyone around—

Drink this and drink that!

Whatever is sore

In my throat is fed up with all these

Commands

And leaves town.

And, here is a piece by Maryna, a 14 years old:

Good afternoon, sister, how is it

In heaven? Quiet, yes?

Without fear and night. We’re

In the basement, talking

Of you, sister. Explosions

Again, and again, mother whispers:

“Thunder…”

Mom insists: “Thunderstorm.”

But see, the war stares at us.

I can still see the men with guns,

Your thin figure, Mother’s

Shouts. And my soul

Zigzags to heaven. Next to God

It is calm and no one tortures us, sister.

Only your doll is awkward

Without you. Many dolls

Without children live here. Here in this

Country: many awkward dolls,

Cars, bears in tattered jackets,

Dresses, pants. We remember

You. We are without you. Here, in Ukraine.

These poems, the tonalities of them, are quite different. That’s what I see in Ukraine as I visit my family there. At night there are air-raids, but in the mornings, people go to cafes, and there are lines to get married, sometimes as long as a block. And this is what we need to see in the West when we speak about the war. Not just the horror that our American TV shows us, but how people survive the grip of war.

The horror is real. Just the other day, Oleg texts:

“We’ve been under fire all week at night: either drones or missiles. And in the third year of the war, I suddenly felt psychological fatigue and fear. When the alarm goes off, you immediately look at the Telegram channels: What are they shelling us with? If it’s drones – well, you can relax a little, they’re usually shot down almost 100 percent of the time. They do, however, fly in waves. That is, they shot down the first batch, and you read that the second wave of drones is flying in from the sea. That’s why the alarm can last a long time. If it’s conventional cruise missiles, there’s also a high probability of being shot down, since the projectile flies predictably.

The worst thing is ballistics, that is, a missile flying up and then emerging from the sky at a target. It flies very fast. That’s why when you see a message about ballistics, you immediately look – where is the target moving? If it’s Odesa, they write that you have 2 minutes to hide. But where to hide? You can’t run to the shelter in 2 minutes. And so you sit in the corridor and look at your watch. Waiting for it to arrive. Quietly and scary. Because, indeed, two minutes pass and there’s an explosion. And you’re glad that it finally exploded. These two minutes of waiting are the hardest for the psyche, you don’t know where the missile is aimed and where it will explode. It might explode with you. But when it explodes, you understand that it’s far away from you, and you can breathe. Until the next missile.”

Meanwhile, despite this, the poetry studio for children in Odesa has been operating now for over a year. You can find all kinds of information about it at www.poemsnotbombs.org

But perhaps, most importantly, here is what kids themselves say:

Anna Polyanska (15 years old):

“My name is Anna Polyanska, I am 15 years old. I started writing poetry at the beginning of the war. When it was scary, writing poems distracted me from what was happening around me. Why poems? Because I really like rhyming, and also, in a poem, I can briefly convey my thoughts.”

Agnieszka Mokszycka:

“My name is Agnieszka Mokszycka, I am a blind girl. Poetry is the source of my inspiration, from which I can both draw water and fill it with feelings that I rhyme. Despite my disability, I try to live like everyone else. We must remember – our strength is in our weaknesses. I love the rain, which most people usually don’t like, and animals are everything to me. I believe that love will save the world. I want to say that poetry is my driving force, and rhymes have completely changed my life.”

Yulia Shevchenko (11 years old):

“My name is Yulia Shevchenko, I am 11 years old. I love drawing, and when I have time, I write poems. I was born in Mariupol, but due to the war, I had to move. I wish everyone success.”

Oleksandr Borysov (16 years old):

“I always thought I would never leave my village. When I was little, I dreamed of becoming a farmer. But now, being thousands of kilometers away from home, I only dream of returning to the best village with the melodious name of Muzykivka in Kherson. I started writing poems in primary school but didn’t show them to anyone until I filled an entire notebook. When I first participated in a regional poetry contest and won a prize, I took it more seriously. All my poems are ‘from my life’. I don’t want to write about the war, but my heart is there, in my homeland.”

Ksenia Bereza (14 years old):

“My name is Ksenia Bereza. I am 14 years old. I have lived my whole life in the beautiful seaside city of Odesa. I love writing poems and dance, study French, and am deeply involved in mathematics.”

Oleksandra Shved:

“My name is Oleksandra Shved, but my pseudonym is ‘Sashenka Teapot’. My mother came up with it because I love tea too much. When we lived in Kherson, we had a tradition of drinking tea every evening after a hard day and talking to each other. But after our hometown was occupied, we had to move to Odesa, and this tradition was interrupted. However, it seems my creating poems unfolded anew here: previously, I only wrote stories, but due to the sadness of the move, words started to form into poetry lines on their own. I wrote a lot and in different languages: I liked writing in English the most because I could keep some secret of my rhyme; my poems in Ukrainian seem more honest and sincere, revealing my true self.”

Mykhailo Kutsak (14 years old): “My name is Mykhailo Kutsak, I am 14. Poetry for me is a way to testify to my existence.”

Victoria Pereverzeva:

“I, Victoria Pereverzeva, lived in the Kharkiv region. The war forced me to leave my native village, and my house was destroyed, but literature helps me cope with the pain and sadness that often envelop me due to our painful present. Literature allows me to forget and feel myself in another faithful world. Besides loving to dive into the wonderful world of reading, I also write myself. I enjoy reading poetry and sometimes write poems myself, especially when emotions overflow. Literature is something that has been, is, and will be part of the spiritual essence of people, their strength and salvation at the same time!”

Yulia Tesliuk:

“I, Yulia Tesliuk, am a 10th-grade student of Lyceum No. 122. I live in Odesa and love my wonderful seaside city with all my heart. I like writing poems and prose. Personally, for me, poetry is a harmony of feelings, thoughts, impressions, and ideas. After all, by reading a poem, you can understand the beauty of nature, the meaning of life, and your own place in it. Thus, poetry has given me the understanding that the world is an endless whirlpool of inspiration and love – love for language, sounds, and life.”

Oleksandra Halyshcheva:

“My name is Oleksandra Halyshcheva. Poems, for me, are primarily emotions that can only be conveyed through images and rhyme. The best usually comes from writing about what hurts. Developing this idea further, I come to the conclusion: my poetry is my tears, and the works inspired by the war are the weeping of the whole nation. Something like that. I also love tea ceremonies, they calm me down, especially during air raids.”

Sofia Yatsura:

“My name is Sofia Yatsura. Since the start of the full-scale war, I stayed for a long time in Kamianets-Podilskyi. That’s where I wrote my first poem. Through poetry, I like to convey my inner state and also open people’s eyes to the situation in Ukraine.”

Kyrylo:

“My name is Kyrylo. I live in the city of Zmiiv, Kharkiv region. My mom taught me to write poems. Very often before bedtime, we played a rhyming game. We would name a word and come up with a rhyme for it. Then I started composing my first little poems and various fairy tales. So, it all started with a game, and now it’s more than a hobby. I hope poems will stay with me in the future. Thank you.”

This is all thanks to the poets who teach at the Odesa’s Kids Poetry Studio, whose poems are gathered here into an exclusive feature for Plume.

Some of the poets are painters, sculptors, others work at museums, or are scientists, or computer specialists. Others work at architecture preservation, teach or translate. Some of them are Russophone, others write in Ukrainian.

Aside from their work with kids in a time of war, they are all serious, sophisticated poets. All have published work in respected journals and presses. They all also translate poetry from around the world into Ukrainian. When Putin is trying to close the city, shut down its conversation with the world, sew discontent, make people afraid, these poets start conversations across borders and bring poetry to kids in their own streets.

Ilya Kaminsky, October 15, 2024

This feature is dedicated to the memory of Arkady Shtypel, who passed away on Oct 23, 2024.

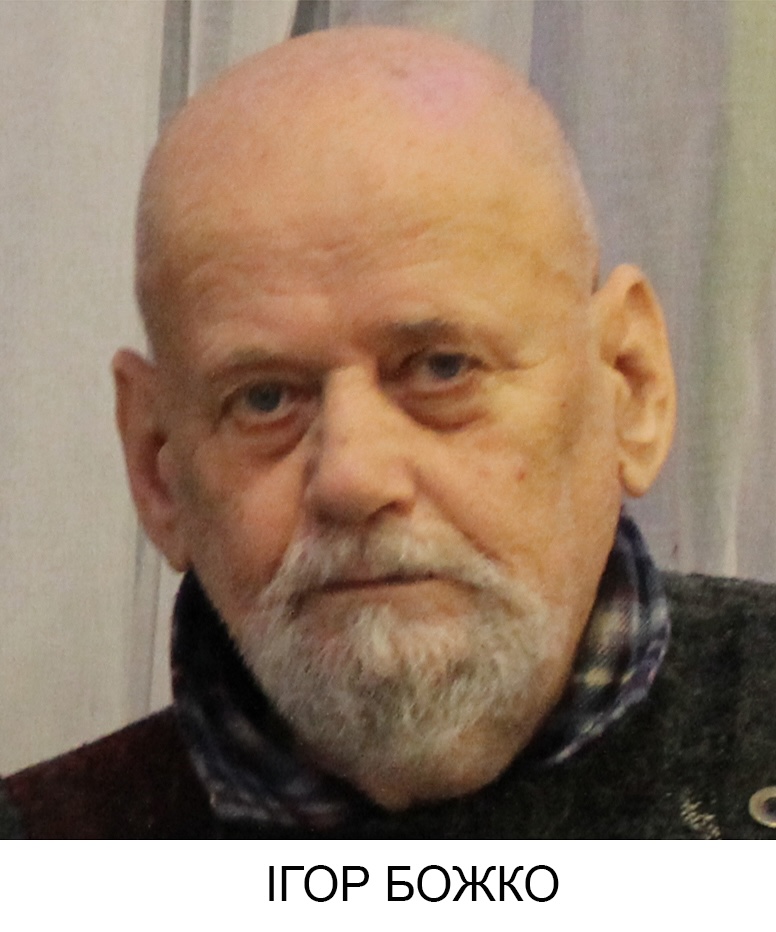

Igor Bozhko /Игорь Божко

Igor Bozhko is an artist. His paintings can be found in the National Art Museum of Kiev as well as other museums across Ukraine. His prose and poetry have been published in several collections in Odesa, as well as in almanacs in the U.S. and Israel. He has also written screenplays for Kira Muratova, including “Kotel’naya No. 6” (“Boiler Room No. 6”) in “Tri Istorii” (“Three Stories”).

March suspended above

over the roofs a sickle glides

as if in fright the stars gaze

not recognizing each other.

Below with dog I stand

carrying on my shoulders

the cargo of unrecognizability—

the dull burden of goodbyes.

March bids farewell with water

with a half-crescent moon

reflected in each puddle

at the very bottom—just there.

март над головой висит

серп над крышами скользит

звёзды смотрят – как с испуга

и не узнают друг друга.

я с собачкою внизу

на своих плечах несу

груз неузнавания –

глупый груз прощания

март прощается с водой

с половинчатой луной

в каждой луже по луне

там – на самом дне.

*

From morgue to crematorium

out their flats the aged flee

not steppe nor sea will sing to them

and ‘tween fingers, merely dust

Baptists chant in mournful tones

“Tatiana’s letter” to themselves

orchestral waves of hoary sounds

tremble through the shroud of death

out their flats the aged flee

unneeded, unwanted, alien

atop the bed the moonlight sleeps

a nun—arrived from heaven.

из морга – прямо в крематорий

уходит старость из пятиэтажек

не отпоёт её – ни степь / ни море

останется меж пальцев – только сажа

лишь иногда баптисты (над своими)

«письмо татьяны» скорбно прогнусавят

оркестрик жидкий звуками седыми

качнёт пристроенный на табуретках «саван»

уходит старость из пятиэтажек

никчемная / не нужная / чужая

на ветхую постель луна потом приляжет

монашкою – пришедшею из рая

Translations by Wendi Bootes

if something that strikes nearby explodes

the cars start wailing deafeningly

the cats and dogs have got used to it –

in an instant (as if they were never there)

they hide in the cracks

as the poor cars continue to wail bitterly

until their owners come out

and calm each one like a small child.

but love always exists

both before and after the impact

in the young neighbors (newlyweds) who linger behind

the thin wall of a Khrushchev-era apartment block

for just a moment (the moment of the explosion)

the sounds characteristic of love fall silent

and then the conversation of the rocked

bed with the universe resumes.

01.26.24

якщо поруч розривається те що прилетіло

то дуже сильно починають скавчати машини

коти та собаки вже звикли –

в одну мить (наче їх тут і не було)

ховаються по щілинах

а бідні машини продовжують скавчати на всі голоси

поки їх володарі не вийдуть

і як малу дитину не заспокоять кожну.

а от любов існує завжди

як до прильоту так і після нього

у молодих сусідів (що тільки-но побравшись)

мешкають за тонкою стінкою хрущовки

тільки на якусь хвилину (на момент розриву)

замовкають притаманні коханню звуки

а потім знову починається розмова –

розхитаного ліжка з всесвітом.

26.01.24

Store Window

a young vagrant somewhat unsound of mind

who lives on the corner of two dwarf streets

stands in front of a women’s lingerie store window

making suspicious movements with his hand (which is in his pants pocket)

on the glass of the showcase / a series of changing

photos of nearly naked women appears

but the vagrant does not make his pocketed gestured for each

–only for the one who looks him straight in the eyes

only for the one who whispers hot words

when she appears, the movements of the enamored admirer

become more lively

and he also brings out: “my dear / how beautiful you are

I love only you, the others are not mine, the devil take them”

such is the diverse world of our love.

that women’s lingerie store

is located next to a trolleybus stop

where I wait for my trolleybus every evening

forced against my will to look at that damn store window

and compelled to admit that the woman

who looks you straight into the eyes is blessed

with extraordinary powers of attraction

while not that beautiful of face

her features have everything

that pleases the lamplight

the long loneliness of night trees

and those obsessed with whispered words.

01.27. 24

ВІТРИНА

молодий бомжик – який ще й несповна розуму

що мешкає на розі вулиць двох карлів

стоїть перед вітриною магазина жіночої білизни

и робить рукою (яка у кишені штанів)

якісь підозрілі рухи

на склі вітрини / змінюючи одна одну

з’являються світлини майже оголених жінок

але бомжик не на кожну з них

робить свої кишенькові рухи

тільки на ту що дивиться прямо в очі

тільки на ту що промовляє гарячі слова пошепки

коли вона з’являється рухи закоханого

робляться більш жваві

і ще він промовляє– «люба моя / яка ж ти красива

тільки тебе люблю а інші то не мої – то чорта»

от такий він різноманітний світ нашого кохання.

той магазин жіночої білизни

знаходиться поруч з тролейбусною зупинкою

на якій я кожного вечора чекаю свій номер

і міма волі змушений роздивлятись ту кляту вітрину

та змушений зізнатись що та з жінок

що дивиться прямо в очі – одарена

якоюсь незвичною притягальною силою

вона не така вже й красива на обличчя

але у тих рисах є все –

що так подобається ліхтаревому освітленню

довгій самотності нічних дерев

та помішаним на словах – що промовляють пошепки.

27.01.24

Translations by Philip Nikolayev

Photo credit: Sergey Gevelyuk

Maya Dimerli /Майя Димерли

Maya Dimerli is a poet, writer, and translator. Born in Odesa in 1973, she is the author of the book of poetry Na Grani /On the Edge (2014) and Smerti net! (no yest’ Barmaley) /There is No Death! (But There is Barmaley), a 2017 book of children’s stories for adults. She is also the author, project manager, and translator (from Japanese to Russian) of Desyat’ Nochey Groz /Ten Nights of Dreams (2017) by Natsume Soseki, the founder of modern Japanese literature. Currently, she is the Head of Office for Odesa UNESCO City of Literature.

Theater of military action.

On the stage is War — a half-naked, filthy old woman with a baby in her arms:

“I come to you from the Kazansky station

And I bring with me an orphan

With an icon of the Virgin Mother in its mouth.

This icon I painted myself.

Now I am the true mother of the orphan.

In its ears cellos squeal,

While I appear as Botticelli’s Venus

In all her irresistible nudity.”

Intently scratching her thin scalp,

She continued: “I have not said everything.

Let the faint of heart be led from the hall

And the meek lose their temper.

My words stop the ears of asses

They who pawn souls, whose carcasses

My eternal god with deft hand

Strangles and hangs.

His art seeks perfection,

So that you feel orphanhood as bliss

At the other end of a leaden gesture

To the end of all worldly paths.

Revealing beauty to the evil world,

I take everyone into my arms.

And with the sacrament of the Sinful Conception

I birth you with an icon in the mouth.”

8.18.14

Театр военных действий.

На сцене Война – полуголая и грязная старуха с младенцем на руках:

«Я к вам пришла с казанского вокзала

И принесла с собою сироту

С иконой Богоматери во рту.

Икону эту я сама писала.

Теперь я – мать родная сироте.

В его ушах визжат виолончели,

А я кажусь Венерой Боттичелли

В своей неотразимой наготе».

Самозабвенно жидкий скальп скребя,

Она сказала: «Я не все сказала.

Пусть слабонервных выведут из зала

И каждый смирный выйдет из себя.

От слов моих закладывает уши

Ослов. Они закладывают души.

Их душит и подвешивает туши

Рукою ловкою мой вечный бог.

Его искусство ищет совершенства,

Чтоб ощущать сиротство как блаженство

На том конце замедленного жеста

Вам до скончанья всех земных дорог.

Являя злому миру красоту,

Я принимаю всех в свои объятья.

И с таинством порочного зачатья

Рожаю вас с иконою во рту».

18.08.2014г.

*

In the dead of night, across the foggy sky

Floated a man with a candle in a jar.

Alas, in the dark one cannot see

Nor drink from a glass.

Behind every rim of a full glass

A drunken month enters from the fog

And pocket knife in hand,

He cuts without any blade.

He knows that the East—

Is an ether of blood.

That the West—walled off,

The North—forlorn,

And the South—several-sided

And tense.

And there is no escape, dear friend,

From the multi-faceted jar,

Where months, turned to a year, surround you

And you sail across the sky to a hunter

Through his fog,

And in his jar.

And it is only thanks to your candle

That you never see anything at all.

2014

Глубокой ночью по небу в тумане

Плыл человек со свечкою в стакане.

Увы, во тьме не различить ни зги.

И выпить из стакана не моги.

За каждой гранью полного стакана

Выходит пьяный месяц из тумана

И, перочинный нож в руке держа,

Он режет безо всякого ножа.

Он знает, что Восток –

что кровосток.

Что Запад – заперт,

Север – серд да болен,

А Юг – многоуголен

Да туг.

И никуда не деться, милый друг,

Тебе от многогранного стакана,

Где годом обступили месяца

И ты плывешь по небу на Ловца

В его тумане,

И в его стакане.

И лишь благодаря своей свече

Ты ничего не видишь вообще.

2014

Translations by Wendi Bootes

We Stepped Outside Our Door

We stepped outside our door

and stumbled

and flew together

like two birds without wings.

It’s holding hands that saved us.

That was the only thing

that kept us falling happily

into the ground.

To think of all the people

who weren’t as lucky–

Мы вышли за порог и оступились

И полетели, полетели вместе

Как птицы, у которых нету крыльев.

И нас спасло лишь то, что мы держали

Друг друга за руки,

И только потому так счастливо

Опять упали в землю.

Как жаль всех тех,

Кому не повезло…

heavenly father

my father long in heaven

a lifelong officer

used his perfect weaponry

to flog a dead horse

he was more or less ideal

though utterly dangerous

Nirvana gave him a medal

for his great self-discipline

and victory over self

he wore the radiant disk

in the center of his service cap

like a star on his forehead

my father felt shitty like Shiva

it’s sad when your life is destruction

Mama-Shakti-and-Mama-Durga

was frighteningly jealous

when he visited kind fairies

in his suede sleigh

in the morning he would return

in a dirty waistcoat

his mustache gone his Party card lost

his honor sullied

then Mom and Dad danced ecstatically

with swords and abandon

but those mornings Dad’s hands shook

just like Shiva’s

all four hands dropping things

Mom understood this

she stood on his heart chakra

performing a pirouette

by the way kids and soldiers

loved my parents

for all the candy and bullets

for their charisma and talent

it was a time of peace

and the burden of life

it was and it was and it will be

an endless and hackneyed song

which has no meaning or moral

only a shining path to Nirvana

and the bright future ahead

мой отец давно небесный

был при жизни офицером

и из пушки совершенной

он палил по воробьям

был он в целом безупречен

и не менее опасен

он носил медаль “Нирваны”

за победу над собой

в центре тульи на фуражке

желтою сиял кокардой

и казалось будто это

у него звезда во лбу

но у папы как у Шивы

было на душе паршиво

потому что очень грустно

в жизни только разрушать

мама-Шакти, мама-Дурга

папу страшно ревновала –

он летал к прекрасным пери

на сафьяновых санях

и под утро возвращался

в перепачканном камзоле

без усов, без партбилета

честь мундира уронив

и тогда они плясали

вместе с мамой экстатично

страстно и самозабвенно

танец с саблями в руках

но у папы как у Шивы

поутру дрожали руки –

все четыре бесполезны

всё валилося из них

мама это понимала

и восставши на пуанты

на его сердечной чакре

исполняла фуэте

кстати дети и солдаты

обожали маму с папой

за конфеты и патроны

за харизму и талант…

это было время мира

это было бремя жизни

это было это было

это будет без конца

у избитой песни этой

нет ни смысла ни морали

только светлый путь к Нирване

только радость впереди

01.01.2022 г.

Translations by Olga Livshin and Andrew Janco

Maria Galina

Maria Galina is a poet, translator, and prose writer who incorporates strong elements of fantasy and myth into her work. As a critic and cultural sociologist investigating contemporary mass literature, she is the author of several monographs addressing Soviet and post-Soviet SF as a social and cultural phenomenon.

Everything looks the same as it was, the bed and the table

The armchair in the corner should be reupholstered

His wife has a hundred and one moles, as before

A crack in the ceiling reminds of a flying crane

In the morning, his dog pokes his wet nose into my face

On the left front paw there is a spot the size of a nickel

Only twice he dreamed of a reflection of fire in the black sky

Either a burning field or just a thunderstorm

Favorite cup with a kitten

Outside the window

Oily rainbow of street lamps

Oh, my God, he will never leave here

The joyful paradise of early love games

How he rushed from here to the big games that men play

Under the black sky where the stars spin like a wheel

How he came back, matured, settled

Got a job, started watching HBO series at night

Everything is the same, only an ending

of ‘Game of Thrones’ he did not know before.

Все осталось как было кровать и стол

Кресло в углу обшивку надо бы поменять

Родинок у жены как раньше сто и одна

Трещина на потолке похожа на летящего журавля

Собака с утра тычется мокрым носом в лицо

На левой передней лапе пятно размером с пятак

Всего два раза приснился в черном небе отсвет огня

То ли горящее поле то ли просто гроза

Любимая чашка с котиком

За окном

Нефтяная радуга уличных фонарей

Он никогда не уйдет отсюда боже ты мой

Из этого рая радости ранних любовных игр

Как он рвался отсюда в большие игры мужчин

Под черным небом где звезды вращаются колесом

Как он вернулся остепенился осел

Устроился на работу сериалы по вечерам

Все как прежде только другой финал

У игры престолов которого он не знал

*

Sometimes it seems that a cloud of light passes very quickly overhead,

so that suddenly one can see in all directions

as if everything were flooded with penetrating radiation,

so that the soilbecomes transparent,

and the entire thickness of the earth

also becomes transparent:

its black earth covers,

its industrious microbes,

its fossil brooches and coins –

all so clear, tangible and at the same time as if not quite real,

not objects, but rather ideas of objects,

the intersection of shining planes,

grass pulsating with myriads of plant cells,

the pearly valves of cockles and heart-eaters,

arrowheads, the brocade of funeral boats,

so many gemstones, druse of rock crystal,

glowing marvelous treasures,

incredible finds,

so that the eye does not immediately distinguish

a string of quiet, almost imperceptible shadows,

building up, breathing down each other’s necks,

endless ranks disappearing beyond the horizon…

they are urgently transferring to the camps

for the prisoners of war

those, who

didn’t listen to their mothers,

didn’t wash their hands before eating,

didn’t give up their seats to elders on the bus or subway,

didn’t read the minutes of the congress,

didn’t remember by heart the names and surnames of the Politburo members,

didn’t applaud standing up,

didn’t tell the truth to the powers that be,

didn’t hold their ground,

didn’t dare,

didn’t commit adultery,

didn’t murder…

Иногда кажется, что над головой очень быстро проходит облако света,

так, что вдруг становится видно во все стороны света

словно бы все заливает проницающее излучение, так что почва

делается прозрачной,

и вся земляная толща

тоже делается прозрачной:

черноземные ее покровы,

трудолюбивые ее микробы,

ископаемые ее фибулы и монеты –

все такое четкое, осязаемое и в то же время как бы не совсем реальное,

не предметы, а, скорее, идеи предметов,

пересечение сияющих плоскостей,

трава, пульсирующая мириадами растительных клеток,

жемчужные створки сердцевидок и сердцеедок,

наконечники стрел, парча погребальных лодок,

столько самоцветных камней, друз горного хрусталя,

светящихся дивных кладов,

невероятных находок,

так что не сразу различает глаз

вереницы тихих, почти незаметных теней,

строящихся, дышащих в затылок друг другу,

бесконечные, за горизонтом исчезающие шеренги…

это в срочном порядке

перебрасывают в лагеря для военнопленных

тех, кто

не слушался маму,

не мыл перед едой руки,

не уступал старшим место в троллейбусе и метро,

не читал протоколы съезда,

не помнил наизусть имена и фамилии членов политбюро,

не аплодировал стоя,

не говорил правду в лицо сильным мира сего,

не удержал оборону,

не отваживался,

не прелюбодействовал,

не убивал…

Translations by Anna Halberstadt

Alexander Hint

Aleksandr Hint was born in 1964, graduated from Odesa State University, and has worked for 30 years as a computer specialist. Author of two volumes of poetry, he writes both in Russian and Ukrainian and has recently translated the volume of Regina Derieva’s Selected Poems into Ukrainian. He lives in Odesa.

In the mailbox of a deceased person

anything could be found

soggy booklets

receipts

last year’s invitation

a letter from a woman

with a rhetorical exclamation “Where are you?”

Evening gluten unobtrusively

highlights the number circled with a marker

on the bottom of the mailbox sprinkled with rust

a New Year card with a stupendous stamp

The spider is late, after the summer,

to decorate the lid, which was until recently still green

And the postman

keeps carrying invisible newspapers

as the last proof of his existence

В почтовом ящике умершего человека

чего только не бывает

размокшие буклеты

квитанции

прошлогоднее приглашение

письмо от женщины

с риторическим восклицанием «где ты?»

Вечерняя клейковина ненавязчиво

подсвечивает номер, обведенный маркером

на дне присыпана ржавчиной

новогодняя открытка с фантастической маркой

Паук опаздывает после лета

декорировать крышку, недавно ещё зеленую

А почтальон

всё носит и носит невидимые газеты

как последнее доказательство существования почтальона

*

On a purple evening, at the yellow hour,

through the foam of neon plexiglass

a snowflake flew and fell into a tear

that just left the eye –

From ads of tropical seas and cheap apartments

it trembled for a while on the left cheek

and got extinguished, crawling back into

the liquid crystal world that had just left the eye

January resin hardened onto the screen

Well, she said, it will get difficult now

How does one play a stringless allegro on the violin

or without violin on the strings

Freeze or leak or just slide

until the end of the show, fall on the rubble

pretending that a crystal in a tear shell

is actually a tear that hardened in the sky

Фиолетовым вечером, в желтом часу

через пену неонового плексигласа

пролетела снежинка и попала в слезу

только что вышедшую из глаза

От рекламы морей и дешевых квартир

что вильнула на левой щеке и погасла

уползая в жидкокристаллический мир

только что вышедший из глаза

Застывала смола января на экран

ну и вот, говорила, сейчас будет тр

как бесструнно аллегро на скрипке играть

или без скрипки на струнах

Замерзать или течь, или просто скользить

до конца представления, падать на щебень

выдавая кристалл в оболочке слезы

за слезу, затвердевшую в небе

Translations by Anna Halberstadt

Vladyslava Ilinska / Владислава Ильинская

Born in 1984, Vladyslava Ilinska lives and works in Odesa, Ukraine, and has a BA in philology from Odesa Mechnykov National University. She began to write poems when she was six, and published her first work in Vecherniaia Odesa (Evening Odesa) as a child. In 2014, she published her first collection, Igry razumu (Games of Reason) and her second, Anekdoty o dozhde (Stories About Rain), in 2020. Vladyslava’s work has been published in many journals, including SHO and Raduga. She has participated in literary festivals both in Ukraine and abroad, and is a winner of the Iu. Kaplan Prize.

The last ship will sail from the pier

its distant path by clouds traced

only the seasick will remain

as sluggishly the mouth shifts taste

eyes grow heavy under bed covers

while timid smoke slips from the hearth

each morning out the hall they are led

unaware the sleep giver’s hand

the winsome bride stretched on the sand

will remain alone in her torn veil

ancient manors will continue to stand

portals of epochs, killers of people

from the cradle will flee the final rays

memory will float past the rusty horizon

leaving only cruel aches and haze

so ends reason

so ends the season

7.12.21

последний пароход отправится с причала,

очертят облака его далекий курс

останутся лишь те, которых укачало,

пока сквозь сон слюна во рту меняла вкус

слипаются глаза под тяжестью одеяла,

застенчивый дымок ползет от камелька,

но утром как всегда их выведет из зала

не знающая сна дарителя рука

лежать на берегу красавица невеста

останется одна в растерзанной фате,

останутся стоять старинные поместья

порталами эпох, убийцами людей

последние лучи сбегут из колыбели,

и память уплывет за ржавый горизонт

останется туман и жесткое похмелье

закончится резон

закончится сезон

12.07.21

Translation by Wendi Bootes

“summertime”

idiots take idiots for idiots,

consistently, magnanimously embarking on their city strolls…

an old buddy from school becomes a most predictable bot,

bored and baring his bulky beard…

you read your feed, then feel fed up with it, summer leaves

аnd you see flying overhead

eighteen posts a meter and they’re all like

“а marathon runner is first to win last place”

quick! turn off the computer and take a walk toward the beach,

notice how, one after another, effuse with memories,

silver waves are weaved together into a gray ball of yarn,

competing for a spot on the hot sandy portico.

a smorgasbord of travelers take in the light completely,

snacking on samosas, drinking mitsne Chernihivske beer,

while on a folding chair at the pier a poet is sitting,

offering his little book of jokes to visitors…

drinking up the last salty summer day,

take my word, believe you me, come and see:

this city is so pervasive that summer here repeats three times over.

летнее

идиоты держат идиотов за идиотов,

планомерно, вальяжно прогуливаясь по городу…

однокашик становится самым обычным ботом,

отпустив беззаботно болтаться густую бороду…

ты читаешь ленту – приходит ленность, уходит лето

и летят над твоей головой шрифтовыми стаями

восемнадцать постов на метр и все об этом:

«марафонец достигнет первым последней стадии»

выключай поскорее комп, прогуляйся к пляжу,

наблюдать, как одна за другой, наливаясь памятью,

серебристые волны плетутся в седую пряжу,

соревнуясь за место на жаркой песочной паперти.

ассорти из приезжих вовсю поглощает свет,

заедая самсой, запивая «мицным черниговским»,

на складной табуретке у пирса сидит поэт,

предлагая приезжим свою юморную книжицу…

упиваясь последним летним соленым днем,

заруби на носу, на подкорке, на веках вырежи –

этот город зациклен настолько, что лето в нем

повторится четырежды.

Translation by Zachary Nelson and David Kurkovskiy

Yevheniia Krasnoyarova

Yevheniia Krasnoyarova is a poet honored in national and international literary festivals. She is the author of the four poetry collections. Her poems have been published in Ukrainian and international journals, including Khreshchatyk, Soborna Vulitsia, Klyap, Palisadnyk, Alracoba, and Triggerfish Critical Review. She lives in Odesa, Ukraine, and works in cultural heritage preservation.

The girl can fashion a doll out of anything:

from twigs and rags, from her mother’s new scarf.

The girl can cook lunch for her doll

from pond water, from rose buds, from celandine.

The girl knows how to cure the doll’s bruised elbow:

with plantain leaves, grandma’s prayer, a quick kiss.

The doll can be taken anywhere:

to the cellar, to the bomb shelter, to the ambulance.

The doll never cries, and the girl doesn’t either.

Her lips silently recite the words of the grandmother’s prayer.

B l e s s e d… V i r g i n…

The sirens start at dawn.

…H o l y… M o t h e r O f G o d…

Another blast nearby and the windowpane flies into

…M y L o r d J e s u s C h r i s t…

Universe, Universe,

why do you simultaneously contain

this doll made from her mother’s new scarf

and

Russia’s

Kinzhal

hypersonic

aviation

missile

system?

–

Дівчинка вміє з усього зробити ляльку –

з гілочок та дрантя, із маминої нової хустки.

Дівчинка може зварити обід для ляльки –

із води з баюри, із трояндових пуп’янок, з глекопару.

Дівчинка знає, чим вилікувати ляльчин забитий лікоть –

листям порізника, бабчиною молитвою, швидким цілунком.

Ляльку можна взяти з собою куди завгодно –

до льоху, до бомбосховища, до машини швидкої.

Лялька не плаче ніколи, і дівчинка також не плаче.

Губи нечутно перебирають слова бабчиної молитви.

М а т і р… Б о ж а…

Сирени волають з досвітку.

…П р е с в я т а… Б о г о р о д и ц я…

Знов бахнуло поруч і шибка летить у

…Г о с п о д а м о г о І с у с а Х р и с т а…

Всесвіте, Всесвіте,

навіщо в тобі

одночасно існують –

лялька з маминої нової хустки

та

російський

гіперзвуковий

авіаційний

ракетний

комплекс

«Кинджал»?

April ’22

how painful it is to live

this spring

when the blooming of forsythias,

dandelions and nameless weeds

slices the air

and bees buzz like airplanes

i cover the flowers with my hands,

chase cats into basements

to safety, away

but I can’t

hide all the people at once

from the enemy salvos

look how beautiful we are this spring

and how defenseless, God…

Квітень ’22

як болісно жити

цієї весни

і цвітіння форзицій,

кульбаб, безіменних бур’янчиків

крає повітря

і бджоли гудуть літаками

закриваю долонями квіти,

жену у підвали котів –

у безпеку, подалі

а людей –

так, щоб разом, усіх –

не сховати від залпів ворожих

бач, які ми красиві цієї весни

і які ми беззахисні, Боже…

Translations by Philip Nikolayev

Taya Naydenko

Taya Naydenko is a poet and journalist who was born and continues to live in Odesa. The author of the collection All Was Given To Us, she writes poetry in both Ukrainian and Russian and her work had been performed in various theatrical projects in Ukraine.

Memorial

Grandma, the girl asks the building,

Is it true what they say, or have people lied once again,

That supposedly memory about us does not disappear,

That blood spilt on the earth – the earth remembers?

The grandma, luxurious – a marble, in classical spirit.

No one on earth has such a granny.

Grandma looks at the girl made of metal

And lies to her, like she’s lied before all her life,

When she promised that God will protect the innocent…

She lies: The whole world will remember Ukraine!

Меморіал

– Бабця, – запитує дівчина у споруди,

– Чи правду то кажуть, чи знову збрехали люди,

Що нібито пам’ять про нас нікуди не зникає,

Що кров пролилась на землі – та земля пам’ятає?

Бабця розкішна – мармур, в класичному дусі.

Ні в кого у світі немає такої бабусі.

Бабця вдивляється в дівчинку із металу

І бреше їй так, як ще за життя брехала,

Коли обіцяла, що Бог вбереже невинну…

І бреше: – Весь світ пам’ятатиме про Україну!

Translation by Olga Yatsenka

In summer we forgot the sound of the dog’s bark

Come fall, the voice of our own daughters

To hear about shelling with no accent mark:

Is it BakhMUT, or BAKHmut?

Oh, Odesa, busy city by the sea

Mykolaiv, bastion from tyrants…

In both places braids did unweave

At the hands of dead mermaids and sirens.

Come winter, saved up sugar will turn to snow,

Spaghetti rain pelts down ever harder.

Each morning, into the city hastily will flow

Waves of ravens, waves of water.

Happy, despairing, happy again, extreme,

Chilling, heavenly, and Milky.

Sleep without fear, wake up, but don’t scream.

This too will pass…eventually.

The dress will be mended by the wedding, of course,

By the fabric of mother’s vestments–or corpse.

The city which ought to play host to my summer soul…

Oh, Mary, Mary, Mariupol…

Считалка

Летом забывать, как пахнет собака.

Осенью – как дочери пахнут.

Слушать про удар без ударного знака:

То ли на Бахмут, то ли Бахмут.

Ах, Одесса, город приморский, с запросом,

Николаев, град привоенный…

Но и там, и тут расплели свои косы

Мертвые русалки-сирены.

Сахар запасенный зимой станет снегом,

Трубочки дождей макаронны.

Поутру на город несутся с разбегу

Волны-воды, волны-вороны.

Весело, темно, снова весело, дико,

Холодно, божественно, Млечно.

Спи без страха и просыпайся без крика,

Всё пройдёт – и это конечно.

Платье заживает, известно, до свадьбы,

С матери плеча или с трупа ль.

Город, где я летом должна побывать бы…

Ах, Мари, Мари… Мариуполь.

Translation by Zachary Nelson and David Kurkovskiy

Arkadiy Shtypel

Arkadiy Shtypel is a Russian Ukrainian bilingual poet, translator, and author of several works on poetry. He was born in 1944 in the Uzbek city of Kattakurgan during WWII evacuation. His childhood and youth were spent in Dnipro, Ukraine, where he studied physics at university, but was expelled for attempting to create a samizdat literary journal and was at the same time accused of both Zionism and Ukrainian nationalism. After military service, he completed his university studies but never pursued a career in physics. From 1969, he lived in Moscow and published several volumes of poetry and translations. Since 2021, he has been residing in Odesa, Ukraine.

it’s scary

the time interval

(someone’s entire youth)

between

the first

transistor radios

and the first

cassette recorders

though both

have long been obsolete

gone out of use

just like those beautiful

photographic film cameras

that nowadays are used

only by

quirky enthusiasts

of vintage photo technology

and magical photochemistry

while those legendary

typewriters

have at best

become interior decorations

i wonder

will rhymed poems too

fall into disuse

it’s not in vain we’ve been assured by warm summer

жуток

временной промежуток

(молодые чьи-то годы)

между

первыми

транзисторными радиоприемниками

и первыми

кассетными магнитофонами

хотя и те и другие

давно устарели

вышли из употребления

так же как

прекрасные пленочные фотоаппараты

которыми нынче пользуются

одни лишь

чудаковатые любители

классической фототехники

и волшебной фотохимии

а легендарные

пишущие машинки

в лучшем случае

стали украшением интерьеров

неужели

вот так же выйдут в тираж

рифмованные стихи

*

twilight dielight

a wind rises

in detroit or

elektrostal

as grandma or grandpa

read in the cards

weave your light loops

you paper fighter plane

you curtain billow

you empty plastic bottle

roll along the asphalt

you verbs conjugate

and you keep on squeaking

worn out earth globe

along your predetermined axis

it’s not in vain that the shutter

of the otherworldly projector clicks

it’s not in vain

that the one-eyed streetcars vibrate

сумерки вымерки

поднимается ветер

в детройте или

в электростали

бабка дед ли

нагадали

вей легкие петли

самолетик бумажный истребитель

теребись занавеска

катись по асфальту

пустая пластиковая бутылка

спрягайтесь глаголы

скрипи потертый глобус

вдоль обусловленной оси

не зря стрекочет обтюратор

потустороннего кинопроектора

не зря

трясутся одноглазые трамваи

не зря нам обещано теплое лето

Translations by Philip Nikolayev

Mikhail Son

Mikhail Son is a poet and translator from Odesa, Ukraine. Biologist by education, he works for the Institute of Marine Life of the National Academy of Sciences, and translates poems from Belorussian and English into Ukrainian while writing his own poems in Russian. His work has appeared in numerous journals including in Germany and Netherlands.

gods see and know everything as it is in heaven and on earth

they know where to find today’s discounts on crème brulées

where two shall meet, god is amongst them

he’ll be the first to hear the gossip in any village

the voice of the people is god’s voice

gods are delighted when a tyrant gives out the order

gods prefer silence when choking the heirs of a king

save us, dear god, from such defenders

what a woman wants, god wants too

god wants martinis and grapefruit juice

he wants to wear dresses, to walk under the moon

god wants to be caressed between his legs

but a god will be born who doesn’t know what awaits him

and when, over Judea, a star will arise

the wise men will speak, watching the star burn

forgive his father for he knows not what he is doing

for grief be upon the woman who’s wanted by god

and shame to the husband who takes her in

and death to the prophet for bringing us tidings

that god is joy and celebration is

joy to the king from the dance of his most beautiful daughter

a party it is for the soldiers to rip open stomachs of children

and to shepherds who’ve abandoned their flocks

to gaze upon the newborn, lying in swaddling clothes

those who kiss him will throw themselves on the noose

wine will turn into blood where he sits down to feast

on christmas and new year’s

peace will not come for the rest of our days

in cities through which he will pass

where two shall gather, god hangs among them

the voice of the people will fall silent and god will wheeze

father in heaven, may this cup pass me by

before god gives him up and a pig eats him

2018

боги все видят и знают на небе и на земле

они знают где сегодня скидки на крем-брюле

где соберутся двое там бог среди них

он первым услышит сплетню в любом селе

голос народа се божий глас

боги в восторге когда тиран отдает приказ

боги безмолвствуют когда душат семью царя

упаси от таких заступников боже нас

чего хочет женщина того хочет бог

бог хочет мартини и грейпфрутовый сок

он хочет платьице и гулять под луной

бог хочет чтобы его гладили между ног

но родится бог который не знает что его ждет

и когда над землей иудейской звезда взойдет

изрекут волхвы следя как она горит

да простится отцу его ибо не ведает что творит

ибо горе женщине которую хочет бог

и позор мужу что пустил ее на порог

и смерть пророку принесшему нам весть

что бог радость и веселие есть

радость царю от танца прекрасной из дочерей

веселье солдатам вспороть животы детей

пастухов позабывших о своих стадах

узрев младенца лежащего в пеленах

бросится в петлю кто будет его целовать

станет кровью вино где сядет он пировать

в рождество и на новый год

не наступит мир до скончания дней

в городах через которые он пройдет

где соберутся двое ему среди них висеть

будет народ безмолвствовать будет бог хрипеть

отец небесный да минует меня чаша сия

перед тем как бог его выдаст и съест свинья

(2018)

Translation by Olga Yatsenka

Anna Streminskaya

Anna Streminskaya is a poet and translator who’s graduated from Odesa State University and works at the city’s Literary Museum. She is the author of several award-winning books of poetry.

Most importantly, you need to have fast legs,

fast, strong legs, to catch your

prey

or to avoid being the prey, which is also important!

Legs feed the wolf and the journalist,

legs feed the athlete and the ballerina.

With strong legs it is better to dance

your wedding dance,

moving side to side, your beautiful, strong

wings.

For women it is very important to have beautiful

legs –

it helps in love and in careers.

The beautiful long legs are always the winners

on stage –

and this is equivalent to the fast and the strong.

To not get kicked out of the circle dance of life,

to confidently dance life’s can-can,

you need to have strong and beautiful,

fast and long…

But who is wandering there with an uncertain

step

on the long and the tangled?

Some slouched social outcast…

Don’t pay attention! It’s only a poet.

A degenerative creature.

Living on the edge of life,

not willing to dance to the rhythm

of the can-can.

Dancing her own, odd, and

lonely dance.

As it seems to be, a poet is a hieroglyph.

Poets are heaps of hieroglyphs on the junkyard

of life,

disobedient to the demand of time

and laws of natural selection.

Except for, of course, the respected poets

who know how to dance the can-can!

Главное – это иметь быстрые ноги,

быстрые, сильные ноги, чтобы поймать

добычу

или не стать добычей, что тоже важно!

Ноги кормят волка и журналиста,

ноги кормят спортсмена и балерину.

На сильных ногах лучше танцевать

брачный танец,

раскидывая в стороны красивые, сильные

крылья.

Для женщины очень важно иметь красивые

ноги –

это помогает в любви и карьере.

На подиуме всегда выигрывают красивые,

длинные ноги –

и это равнозначно быстрым и сильным.

Чтобы не выбиться из хоровода жизни,

чтобы бодро танцевать ее канкан,

нужно иметь сильные и красивые,

быстрые и длинные…

Но кто это там бредет неуверенной

походкой

на длинных и заплетающихся?

Маргинал какой-то сутулый…

Не обращайте внимания! Это – поэт.

Существо дегенеративное.

Живущее на окраине жизни,

не желающее танцевать канкан со всеми

в ногу.

Танцующее собственный, непонятный и

одинокий танец.

По сути дела, поэт – это такой иероглиф.

Поэты – это груда иероглифов на свалке

жизни,

не подчиняющихся требованиям времени

и законам естественного отбора.

Кроме, конечно же, маститых поэтов,

умеющих танцевать канкан!

Translation by Olga Yatsenka

Translators:

Wendi Bootes is a scholar, writer, and translator. Her writing and translations can be found in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Asymptote, and Modern Fiction Studies, among other places. She lives and teaches in the Bay Area, and holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from UC Berkeley.

Anna Halberstadt is a poet and a translator from Russian, Lithuanian and English. Her poetry has been published in journals such as Caliban, Cimarron Review, Literary Imagination, and translated into Lithuanian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Tamil and Bengali. She published six collections of poetry in English (including Vilnus Diary and Green in a Landscape with Ashes) and four books of translations into the Russian. She received numerous prizes, including the 2016 International Merit Award by Atlanta Review.

Andrew Janco’s translations are published in The New York Times, Ploughshares, and other journals, and are included in the anthology Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine. With Olga Livshin, he is the co-translator of A Man Only Needs a Room, a volume of Vladimir Gandelsman’s poetry (2022), and Today Is a Different War by Lyudmyla Khersonska (2023).

Image credit: Jen Siska

David Kurkovskiy is a PhD student in Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California, Berkeley. David’s primary research languages are Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Yiddish. He has worked as a freelance Russian and Ukrainian translator for the New York Times. David and Zach Nelson have previously published joint translations of Russian and Belarusian poetry in response to the Belarusian protests of 2020.

Image credit: Shalimar Varvoutis

Olga Livshin is the author of A Life Replaced: Poems with Translations from Anna Akhmatova and Vladimir Gandelsman. She co-translated Lyudmyla Khersonska’s poetry collection Today is a Different War and A Man Only Needs a Room by Vladimir Gandelsman. Her work appears in POETRY magazine, New York Times, and Ploughshares.

Zachary Nelson holds a M.A. in Translation Studies from Kent State University. Zachary’s languages of focus and translation, in order, are Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian. He is currently is the Program Director at Global Cleveland, a non-profit in Cleveland, Ohio assisting newly arrived immigrants and refugees in the region.

Philip Nikolayev is a poet and polyglot living in Boston. He translates poetry from various languages. He holds two academic degrees from Harvard and a PhD from Boston University. Nikolayev’s poetic works are published internationally, including such periodicals Poetry, The Paris Review, and Grand Street. His collections include Monkey Time (winner of the Verse Prize) and Letters from Aldenderry. He coedited, with Anna Halberstadt, Lyric Resistance: Ukrainian Poetry of War and Hope, the summer 2024 issue of The Café Review. Nikolayev is coeditor-in-chief of Fulcrum: An Anthology of Poetry and Aesthetics.

Olga Yatsenka is a Belarusian-Ukrainian poet, scholar, and translator who was born in Belarus and grew up in Northern California. She is studying Comparative Literature and Ukrainian studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She translates Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian into English.