Emily Skaja on “It’s the stage of grief where [I become a transparent eyeball].”:

I wrote this poem as part of a series exploring the grief of recurrent pregnancy loss. All the poems share that title, and the first line of each one is “I become [x].” Over the course of the series, I become a ghost, I become stuck in time, I become estranged from myself, etc, and in this poem, I become a transparent eyeball. When I wrote this, I felt impatient with my own progression through grief, how I seemed to be stuck in one stage, and so I wrote these poems to describe what it felt like to go through a number of inadequate transformations. When I came across the Emerson quote that appears in the first line, I was struck by his fantasy of becoming a “transparent eyeball.” He describes wanting to minimize himself by dissolving into his surroundings in order to see more clearly. I was so in my head with grief that it sounded amazing to me to disappear from myself and be replaced by a transparent eyeball. “I am nothing,” Emerson writes, “I see all.” But the allure of absenting myself from grief proved to be false; even if I pretended to be absent, it was still there, waiting for me to deal with it. From that experience, I wrote this poem.

Jim Moore on “The Happiness on the Other Side of Happiness”:

“The happiness on the Other Side of Happiness” could only have been written at Seward Park in Chinatown in New York. It is a joy to sit on one of the benches there and watch the life of the park, the natural world, of course, but also people. It is a park densely inhabited by pleasure: people doing t’ai chi, playing ping pong, running back and forth on playgrounds, flirting, reading, playing chess. The park gave birth to “the happiness on the other side of happiness,” which I suppose is the happiness of being surrounded on all sides by other peoples’ happiness. A happiness I have felt more and more often as I have grown older. Public spaces are where that seems to happen most frequently: parks, cafes, bus stations, boardwalks, sidewalks, public squares. This poem was a joy to write.

John R. Sesgo on translating Karmelo C. Iribarren

This extract from Karmelo C. Iribarren’s You’ve Heard This One Before: Selected Poems (forthcoming from World Poetry Books in Spring 2026) showcases the main elements of his craft: extreme concision, an understated yet piercing irony and a unique handling of rhyme.

While the first two features have been widely discussed in Spanish reviews of Iribarren’s poetry, the third is often overlooked—which may well be by design: as Iribarren has said, one of his aims is to make his sonic effects so natural-seeming that his readers hear and respond to them “without noticing.”

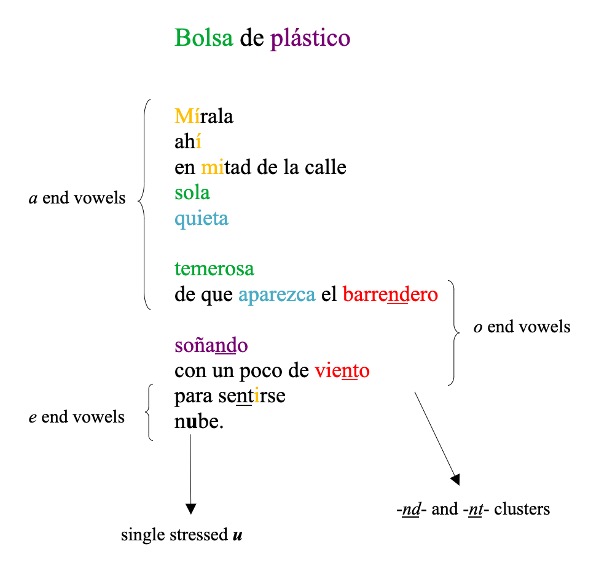

Take, for example, the original of “Plastic Bag,” whose sound patterning I’ve illustrated in this graph.

First—in green, purple, blue and red—are four assonant rhymes: in o-a (bolsa, sola, temerosa), e-a (quieta, aparezca), e-o (barrendero, viento) and, somewhat far apart but still active, a-o (plástico, soñando). Next, in yellow, the m alliteration also highlights a prominent i sound, which does not return (in stressed form) till the emotive sentirse (to feel) in the penultimate line. End-vowel repetitions fall into three blocks, each with its own dominant sound: first six a’s (from Mírala to aparezca), then four o’s (from barrendero to viento) and finally two e’s (sentirse and nube). A striking consonantal feature is how, after only one n in the first half of the poem, eight n sounds anchor every line in the second half, particularly in the clusters –nd– and –nt-.

But it’s in the last line that Iribarren’s sonic skills are most remarkably on display. That nube (cloud) has the only stressed u sound in the whole poem is not accidental: in conversation, Iribarren has called this aural feature “a turn,” in which a vowel is suddenly present or stressed prosodically in the poem for the first time. In this case, Iribarren’s “turn” lifts that cloud even higher, and sharpens the poignant distance between it and the humble bag stuck to the ground.

Faced with this sonic complexity, I think a translator can only settle for various (and necessarily inconsistent) approximations. In “Plastic Bag,” I made sure the /aʊ/ in “cloud” occurs only that once, and finished with the suffix “-like,” to keep a feminine ending (and have an instance of both assonant and consonant rhyme). The other translations in this issue show different kinds of compromises, and my hope is that through them a reflection of Iribarren’s poetry has, however slantedly, come across.

Just north of where I live in east-central Indiana, a sizeable Amish community runs a store for non-Amish customers, selling bulk foods, fresh produce, log furniture, flowers, and baked goods. It’s a pretty drive to Fountain Acres. Plus, if you arrive at the right moment, the Amish girls stocking shelves will start harmonizing hymns. The first time I witnessed this, I gawked, entranced by the haunting lilt of their voices that sound artifactual, caught between time present and time past. Whenever I visit the store now, I linger beside the dried noodles and homemade donuts, browsing longer than I normally would, hoping to hear them sing.

I started drafting “A Drone Over Amish Country” in early 2020 before the first COVID-19 lockdown marooned everyone at home. Since moving to the Midwest from DC in 2015, I’d struggled to write about “flyover country”: what it felt like to have landed in a region that most people ignore but which fascinates me in part for the presence of the ancient past within its sprawling fields and limestone cliffs. This place contains extraordinary caches of late-woodland arrowheads and Ordovician fossils flaking from a landscape as wide and flat as a muddy sea. In fact, 400 million years ago, when Indiana was equatorial, the landscape was a shallow sea.

While sheltering-in-place, it occurred to me that the image of a quadcopter drone hovering over farms still tilled by ox-drawn ploughs offered a rich objective correlative. For me, this image embodies the juxtaposition of cultures that continues to define the United States, even as retrograde politicians enact legislation designed to achieve a pernicious homogeneity. I imagined that the Amish, witnessing unbidden technological “advances” infiltrating their lives, might recall Ecclesiastes 3:15 (“That which hath been is now; and that which is to be hath already been”) or Augustine on eternity in which “nothing passeth, but the whole is present.” Though irreligious, I found strangely comforting the notion that the bones of my great-grandchildren already lie beneath silt and clay deposited by glaciers that receded during the Pleistocene: “time future contained in time past,” as Eliot put it.

Like many struggling with protracted anxieties during lockdown, I turned inward, returning to favorite titles like Marianne Moore’s Collected Poems and Richard Howard’s monumental Alone with America: Essays on the Art of Poetry in the United States Since 1950. Howard, from whom I took the epigraph for “A Drone,” got me thinking about the presence of the present in the past, as well as William James’s more down-to-earth questioning of whether the “time-content of the world” is “one monistic block of being” or if the future gets dropped back into the past without being “virtually one therewith.” These kinds of meditations strike me now as being symptomatic of living through a global pandemic—the same situation through which millions in the recent and distant past have lived and died.

I mention Marianne Moore because, formally, the poem is the result of experiments with syllabic quatrains: stanzas that rhymed XAXA and employed a set syllable count. So line one of such a poem might contain eleven syllables; line two, nine; line three, thirteen; and so on. Syllabic quatrains became a way of breaking myself out of the habit of blank verse, the default form in which I still draft many poems. Though neither composed of quatrains nor syllabics, “A Drone Over Amish Country” began as both, eventually developing into seven cinquains rhyming ABXAB with the second line of each stanza being shorter than the rest. This futzing with form serves as a means of observing poetic traditions without being subservient to them, adding my own slant with cheeky rhymes like “ether”/“either” and “father”/“farther.” Or at least that’s the benign illusion in which I like to work.

Bhisham Bherwani on “Dead Ringers”

A man, a family friend, arranges matchsticks on a divan to amuse a five-year-old boy; the same man, barely recognizable, unexpectedly resurfaces fifteen years later in radically different circumstances and asks the boy’s father for a light for a cigarette. Their backdrop imbued with personal and historical significance, these seemingly unimposing encounters, what Nabokov calls “the match theme” in his memoir Speak, Memory, become emblematic of a genre. “The following of such thematic designs through one’s life,” the author writes, “should be, I think, the true purpose of autobiography.”

To the extent that autobiography informs poetry, a poet may be impelled to follow such thematic designs—and in the process may even broach and grapple with some arcane facet of life. That is how, at any rate, it was for me while composing “Dead Ringers,” when adolescence and adulthood, remote places and coincidences, city and country, art and nature, and memory and the moment serendipitously converged in a design during a snowstorm in Central New York, where I sat in a makeshift study in a basement, astounded by the brilliance beyond the glass patio doors that looked out onto a suburban backyard.

Arthur Brown on “The Studio”:

I first saw paintings by Jason Berger at Ernesto Mayans’ gallery on Canyon Road. Sadly, Ernesto is no longer there. My wife and I have four Berger paintings in our home. The Studio, Brookline (1973), 60″ x 60″, is not one of them. I came across a photograph of it in Lois Katz’s The Paintings of Jason Berger.

What’s in the poem is what I saw in the painting: images of the walls, windows, and floor of the studio, its objects arranged in relation to each other according to the dimensions of the room, the needs of the painter, and the requirements of painting—of color and line on a flat, squared-off surface. For the painter, the painting of the studio existed not only in the medium of paint and its support but also in relation to his body and in the invisible medium of observation, thought, memory, feeling, and time—somewhere between the real and the abstract.

Obviously, a painter who paints his studio is telling us something about the medium of painting, and obviously and inexhaustibly, painting is telling us something about the medium of human existence. It may do so above all in its mysterious translation of three dimensions into two, for we are thereby invited to read into it not only depth but time—to add to it the actual space in which we stand and actual time, now that we have taken the painter’s place. And then by some translation or inversion stranger still, we may seem to add to our own world a dimension neither here nor there but one in relation to being at large.

What I saw in the painting came in part from what I have been reading—less literature since I retired from teaching and more philosophy and books on art. For the past several months I have been reading a wonderfully big book by Pierre Schneider called Matisse. All the poems I have been working on the past ten years have to do with perception and concentrations of perception, with mediums that I hope above all are mediums of participation.