In her personal essay, “Rescuing Ourselves,” Celia Bland reminisces about a tour she took through the Hermitage Museum in 2003. She’s reminded of her visit there seventeen years ago by a recent online tour she took through the same museum. Her memory of the “drab” interior of the museum in which “the floors, walls, and paintings [needed] “a good polish” contrasts with the Renaissance paintings— Leonardo, Breughel, Caravaggio, and Rembrandt—that the tour guide, Ivan, denigrates as “tourist highlights.” But his sudden attention to a small painting by Rembrandt of Christ’s deposition inspires him to wax poetic on the ironic beauty of the painting’s ugly subject matter, specifically Christ’s body as a “slack and repulsive sack of flesh” and the seemingly miraculous light that emanates from it. This “repulsive” image transports Bland into the present, prompting her to contemplate similar “bodies” in the grip of Covid19, bodies that possess the same common oxymoronic ugly beauty as Rembrandt’s painting of Jesus on the cross. Stirred by this mortal awareness, Bland transforms her prose to poetry, concluding with an unwitting prose poem that laments and empathizes. That betrays the complementarity of poetry and art in a moving ekphrastic lament that transcends mere appreciation for exquisite art with electric pathos.

–Chard deNiord

Rescuing Ourselves

I have been touring the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, via an online iPhone film. I sit with my snoring dog on the couch and sun pours in the window as I ramble galleries lit by heavy, gold-encrusted chandeliers. A former palace built by Catherine the great, some of her furniture still sits in the long arcades. There are side tables patterned with inlaid malachite. There are massively-framed paintings and windows that must measure ten-feet-high, fitted with hinged shutters that fold into ormalu-limned casements.

I toured the Hermitage in real time in 2003 — my first trip to Russia — and I was pulled through the throngs by Ivan, a gangly art historian in a polyester suit and desert boots who darted around groups of Americans and Japanese and skipped whole sections of the museum. The galleries were drab, then, even dingy, and the floors, walls, and paintings were in need of a good polish — not unlike the guards: chubby grandmas with charwoman aprons tied tightly over their bellies. They sat against the walls in spindly chairs and didn’t so much call out to a person venturing too close to the art as intervene their fleshy bodies between viewer and painting. From the ceiling hung ancient lightbulbs, globules encasing wire filaments the size of paper clips that cast an anemic glow. I thought they could be museum exhibits themselves.

It was soon clear that Ivan approached art as a lesson, one masterpiece progressing to the next as artists solved “problems.” Titian had solved the problem of color, for instance, so Tintoretto had to solve the problem of light. This progression – i.e., our tour — did not include Leonardo or Breughel or Caravaggio or Cezanne. I politely asked Ivan if we couldn’t see their work, too, and he sighed, and waved a hand before his face. “You want tourist highlights, yes.” Sighing. “No?”

Yes. We paused in a gallery punctuated by the kind of French windows dignitaries open to wave to the mob below. Ivan gestured to a small painting. “Here,” he said.

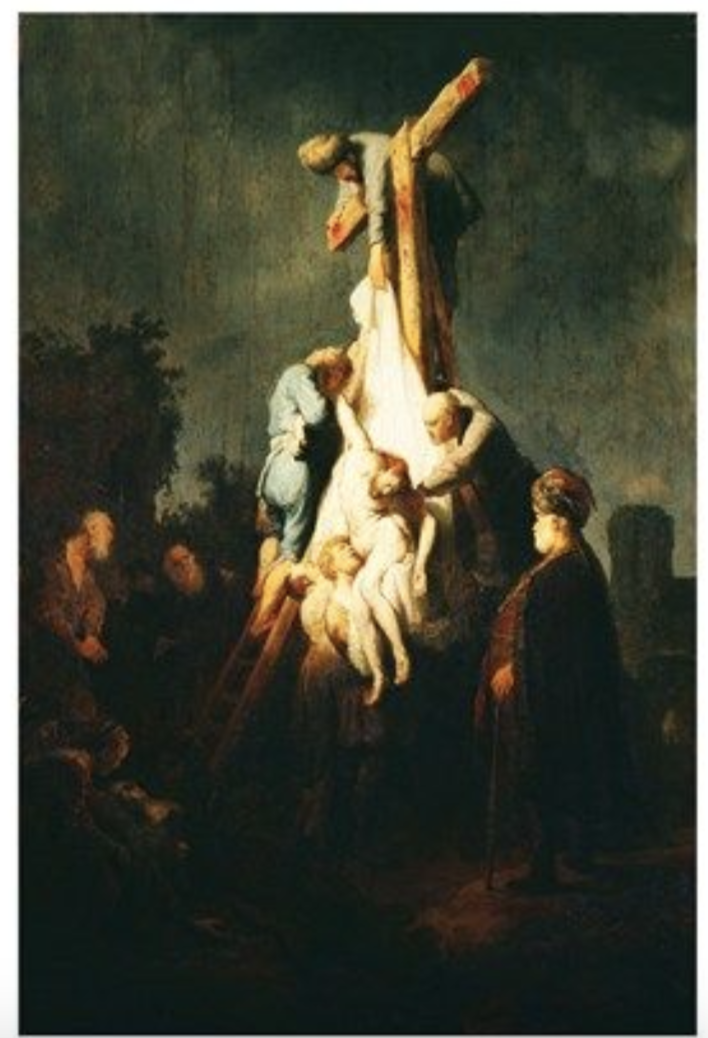

It is a night scene. Spotlight on a cluster of people in the center of the painting’s murkiness. There is Jesus hanging from the cross – quite literally hanging the way a fish dangles from a fisherman’s forked hand. Jesus’s head is lagging lifelessly upon his shoulder. A man stands on a ladder and leans over Jesus’s legs. The man – Thomas? John? — has wrapped his arms around Christ’s knees and is boosting him up so that two men precariously balancing over the cross’s crossbar can loosen the final nail that holds His right arm extended. The arm is angled, painfully stretched. By lifting him, the man on the ladder takes on the body’s weight, a weight we can feel in a naked hip, torqued and awkward, above the bear hug. Once that last nail is extricated, the body will slip to waiting arms, and to a shroud laid on the waiting ground. Ivan says, “One art historian has complained that Rembrandt was a great artist of ugly things. There is nothing,” he pronounces emphatically, “uglier than Christ in this painting. He is truly a slack and repulsive sack of flesh.”

I am shocked. Ivan’s words seem blasphemous. As a Russian. As an art historian. After all, the Hermitage is the museum where, during WWII, art was taken from the walls and hidden in caverns beneath the museum. Where curators lived with the art, in darkness, cold, and hunger, protecting it from the Nazi troops who were bombing and burning their way across ruined Leningrad, where people were, literally, starving. Where people nested in bomb craters under rubble and snow, refusing to surrender. “Rembrandt gives hope to the damned,” says Ivan.

I peer into the dark square of the painting. Where is hope? There is the grieving Mary, fainting at the cross’s base; the stocky apostles in middle eastern dress, clearly not middle eastern but pale, well-fed Dutchmen, comfortable with the tools of their trade, getting the job done. “Where is the source of the painting’s light?” Ivan asks, encouraging me like a child. “It emanates from Christ’s chest,” he explains. “See how it shines? The son of God acts as the sun.” He is smiling beatifically. I notice that his teeth have come only partway through the gums.

I nod but I feel as stubborn and stocky as one of the apostles. The light in the painting comes—obviously — from a candle held by a boy on yet another ladder. But this light is admittedly too bright for a mere candle. It searches the face of a man holding a lifeless burden, faces blank with grief. My gaze and my thoughts wander, catching at other Rembrandts hung in rows on the flats upholstered in a dusty burlap. Every surface in the gallery seems coated with a powdery yellow dust – the same that coats all of St. Petersburg. So much construction! Huge multi-story scaffolding marks buildings renovating on nearly every block. Taking a walk is like moving through a filmstrip of light and dark squares.

I look back into the Rembrandt. In the midst of its drabness, a light, inexplicably strong, irradiates what would otherwise be an unseen tragedy — just another executed human. I feel sure that the light does not emerge from Christ’s body but from the artist’s imagination. He highlights the details we need if we are to share in his loss. A thick hip, a chest, a broken arm, a man patiently bearing his burden, love mixed with

Resignation, with resolution. Nature plays no part in this dumb-show. Nature does not mourn.

Today, this afternoon, pausing in place, I cough, feel my forehead for fever, and pause the film. What gives hope to the damned? I am searching for a single depiction of a corpse. Can I find hope in the extended ligaments of its all-too-human weakness? In the threads of blood crusted along his forehead? Today, my eye is drawn to a huddle of mourners who reach up to take the weight. Shining arms brace a dead man’s descent. Dark arms support his fainting mother. Sorrowing, these bodies are virtually our bodies as we breathe, or struggle for breath. As we hold tight to those who breathe no more.