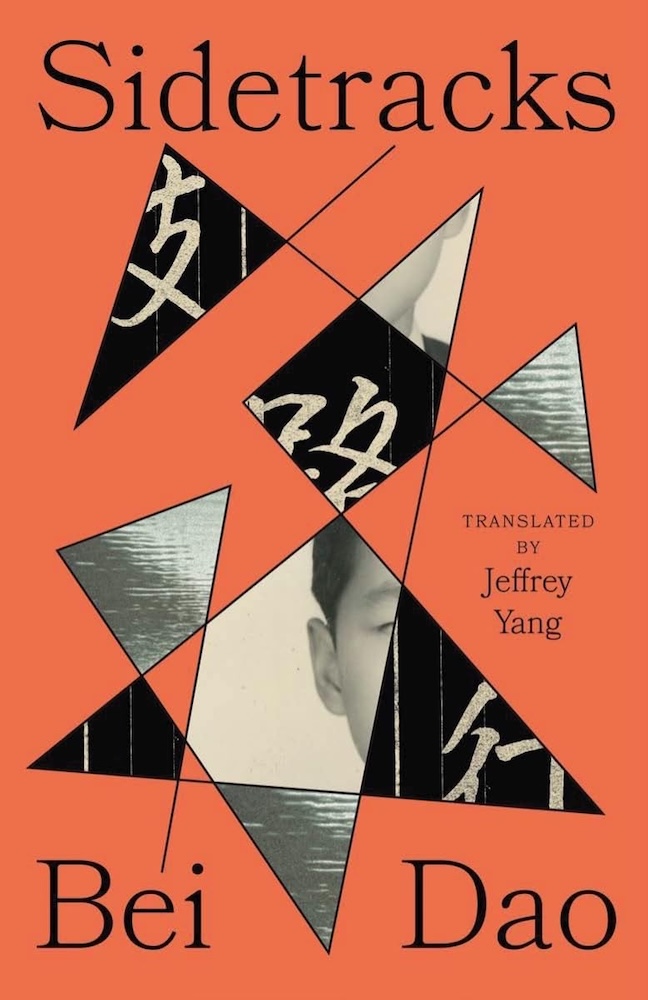

Sidetracks by Bei Dao

Review by Christian Detisch

I have set for myself what I now realize is an impossible task: reviewing Bei Dao. Sidetracks, his first book in fifteen years, a long poem composed in a prologue and thirty-four cantos, presents a challenge to my typical sense of reading, and thus to my typical sense of reviewing. Bei Dao’s method of composition—montage; radical juxtapositions of time, voice, fields of reference; parataxis—makes the issue of excerpting passages, aside from individual images, difficult; but even the individual images are fast-moving, unstable, their meaning liable to mutate within a line, within a word. The effect of the poems, often violent in their velocity, subtle but strange, immediately lucid then determined to derange reality, is akin to atoms colliding in a particle accelerator. One is left to observe the reaction, overawed, enthralled, without a clear sense of its mechanics—and wonder how what happened just happened:

a clenched fist suddenly sets metaphor free

after the explosion two women survivors stagger

out of the movie screen naked toward an actress neighbor

they borrow clothes go into hiding

the times and the undercurrent—Weathermen forever young

they are the wind describe the shape of the wind

you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows

I have no facility with Mandarin, the language in which Bei Dao writes, though I find these renderings very ably translated by Jeffrey Yang and compelling and telling in the ways they move, even dressed in English. The internal rhyme weaved throughout these lines above (free-screen-need; metaphor-stagger-neighbor-forever) provides a certain sonic logic, a connective tissue as the units of language accumulate. Not to say there isn’t otherwise a logic. Meaning accretes (reorients?) as the poem proceeds down the page, acquiring and overlaying its contexts in time, in place, in tone. The hermetic and vatic-sounding phrase “a clenched fist suddenly sets metaphor free” takes on a revolutionary undertone with the appearance of the Weather Underground’s bombing campaigns in the 1970s–and their aftermath. Bob Dylan’s lyrics from “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” from which the Weather Underground took its name, suddenly emerge, brushing into the scene the 1960s counterculture in the United States and all its uneasy energy. And what to make of the fact that this canto, the twenty-sixth in the book, begins by reflecting on the death of Dylan Thomas, the poet after whom Bob Dylan (né Robert Allen Zimmerman) renamed himself?

at the morgue Laughlin identifies Dylan Thomas’s corpse

a semiliterate young girl confirms it—“he wrote poems”

mad Dylan a flock of pigeons sets the church spinning

by the sea’s side hear the dark-vowelled birds

More resonances: like Dylan Thomas, Bei Dao’s reputation extends beyond his home country; and, like Dylan Thomas, perhaps a larger share of his notoriety derives from his biography rather than the poems themselves. Perhaps. Bei Dao has consistently resisted the label of “political poet,” of being instrumentalized as some anti-Communist exiled hero valorized for Western consumption. “I don’t see myself as a representative of such-and-such a trend or political opinion,” he tells Steven Ratiner in a 2001 interview in Agni. “I see myself as an individual who is trying to create a new form of language, a new mode of expression.” (In the introduction to the interview, Ratiner—in a synchronicity too rich to exclude—compares Bei Dao’s poem “The Answer” to Bob Dylan’s song, “Blowing in the Wind.”) One intuits, then, in the semiliterate girl’s final word on Dylan Thomas’s legacy—“he wrote poems”—a hint of hope, that one is known for the work they make, not the brand they’re made into.

At any rate, the recircling and reconnecting of Dylans, their synchronicity within the poem, is at the heart of Bei Dao’s art. The cantos each acquire more and more density, even as they seem at first effortless, casual, at times random. Events, people, images, phrases, symbols, and ideas move cyclically throughout Sidetracks; yet they also pile up topographically, like archaeology, architecture—or the human psyche. The resultant vision is at once far-seeing, wry, acerbically funny (“the speech-language pathologist’s assessment is correct I’m really ready to deliver pizza”), tragic, wise but not priggish; a kind of postmodern Cavafian sensibility in its irony and attitude toward history. Indeed, in his afterword, Bei Dao reveals that the inspiration for this book came from a conversation with a friend who said, “You should write a long poem, something with a sense of history,” a suggestion echoing Ezra Pound’s own characterization, understated yet grandiose, of an epic: “a poem containing history.”

However. A wide gulf lies between giving “a sense of history” versus “containing history.” Unlike The Cantos, that tortured epic that ends in assent to its own perceived failure—“I cannot make it cohere”—the poems of Sidetracks are unburdened by the anxiety of incoherence. Though all those Modernist masters sought out new forms to fit everything in, no form (as they all eventually discovered) can or will contain all of eternity. Even Dante, who composed the most perfect long poem ever written, after whom both Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot modeled their own epics, laments several times within The Commedia that his art cannot sufficiently reflect the grandeur of his vision. This is, I suppose, the problem of genius—no forms capacious enough to mirror the entire mind of their makers. It’s a problem that Bei Dao blissfully doesn’t trouble himself with. These poems admit instants of brilliance but never belabor their point, often speeding off quickly to different territory. I have underlined in my book many such discrete moments toward which I can express only awe, too many to list, but look for instance at:

insomnia is another measure of eternity

or

I master the art of cricket ventriloquy

or

bullets catch up with the metaphors of birds

poetry talks with the tanks

or

liquid mercury streams down the porthole window

What sense of history, in the end, is embodied in writing like this? Writing that seems suffused in a quiet sort of confidence (or is it compulsion?) that what has occurred, and what exists, will not be erased by moving on, but will, perhaps, return, arise again, just as they do throughout these cantos? “I am you,” Bei Dao writes in the closing lines of Sidetracks, “a stranger on the sidetracks /[…] sending letters though tomorrow has no address.” Such a Whitmanic gesture at once asserts identity and expands it, positioning writing itself as the means to navigating contingency. Even as the poems follow the mind into exile, into the unknown, wherever it leads. Even as the “I” behind the poems splinters into a “you,” a “stranger on the sidetracks.” One considers Czeslaw Milosz saying that “the purpose of poetry is to remind us / how difficult it is to remain one person”—or, put in Bei Dao’s formulation, poetry exists to remind us how difficult it is to be “an individual who is trying to create a new form of language, a new mode of expression.” To speak honestly about the incoherence of history; to follow the shape of the mind and regard it as something to be observed, not contained; to remain an individual, even as the world conspires to make us, and all our strangeness, something less than that—Bei Dao, so entirely possessed of his own voice, achieves exactly what he hopes to. He has no imitators. He seems to me among the most important poetic voices we have, in this world or the next.