SOME THOUGHTS ON THE SUBLIME IRONY OF NOTHING AND THE DIVINE IMAGINATION

“The most sublime act is to set another before you.”

William Blake

“Nothing is the force/ That renovates the World.”

Emily Dickinson

*

The legacy of sublime conceits in both secular and religious literature betrays the same ironic muse in an archetypal arc that extends from the earliest Sumerian texts to contemporary literature. Both classical narratives and poetry share a common hierophantic obsession with mining the fruits of uncertainty, mystery, alterity, nothingness, and the absurd in their renditions of the sublime. At the core of their genius lies the working paradox of something in nothing. “Saying nothing…sometimes says the most,” Emily Dickinson wrote to her friend, Susan Gilbert, in 1874, and then this gem in her poem (1562): “By homely gifts and hindered Words/ the human heart is told?/ Of Nothing/ Nothing is the force/ That renovates the World.” Walt Whitman expressed a similar belief in “the force” of nothing in terms of his poetic praxis in canto 44 of “Song of Myself”: “What is known I strip away.” As for the reader of sublimely ironic poems about the double nature of absence she must, like the listener in Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Snow Man” behold “the nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” It is precisely this paradox of nothing’s double nature that sounds so similar to Heisenberg’s Principle of Uncertainty, betraying an existential nexus between absence and presence, nothing and something.

*

Strangeness sustains the imagination in myriad classic texts in the face of nothing with events, facts, choices, reasons, acts, realizations, and outcomes that transcend the ordinary with mystifying weirdness —a fleeing youth at Jesus’ arrest in Gethsemane, the shocking revelation of the bible salesman’s true identity in Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People,” a horrible commandment from God to Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac, the terrible realization by a young man in Oedipus the King that he’s murdered his father unwittingly and then married his mother, also unwittingly, to mention just a few.

A memorable literary synecdoche for the vast array of examples of human unknowing lies in James Wright’s poem “The Heart of Light” in which Wright announces his sublime ignorance to himself first, and then to his reader: “Now that I know nothing, I can die alone.” In admitting to knowing “nothing,” Wright achieves a profound state of enlightenment that is ironically synonymous with Socratic wisdom, allowing him, in turn, to “die alone” in an heroic act of self-enlightenment. Unwittingly but archetypally, Wright describes nirvana in his conclusion to “The Heart of Light” where “lightness of being,” as well as his genius for line breaks, was on full display near the end of his life when he was dying of tongue cancer in Calvary Hospital in the Bronx. Donald Hall tells this risible story about an exchange he had with his dying friend in his introduction to Wright’s last book Above The River: “At one point Jim started to write a note, and paused after the third word. On his yellow scratch pad, I watched him write, ‘Don, I’m dying’—-and then after a tiny pause, as short as a line break—’to eat ice cream from a tray.’”

*

The provenance of the other as a solitary divine entity resides in the earliest Hebrew scripture where infinitesimal others emerge out of Nothing in God’s acts of creation. In choosing an unknowable God whose name is too holy to speak and who possesses a miraculously verbal power to transform “waste, void, and darkness” into natural wonders that are “good,” including mankind, the Israelites defined themselves as an anomalous people with a unique belief in an inscrutably strange deity in the midst of a hostile array of neighbors devoted to anthropomorphic gods. In addition to being strange and different, Yahweh was terrifying, forbidding any graven image of Himself while demanding devotion to moral commandments that Moses received in a mysterious mountaintop meeting with Yahweh where Yahweh revealed only His backside. The Jahwist author of most of the narratives in the Pentateuch, including the two creation stories, possessed a literary acumen for conveying what John Keats would define millennia later as “negative capability”—a preternatural human capacity to exist in “uncertainty, mystery, doubt without any irritable reaching after fact and fiction.” Or as William Blake abjured more succinctly in his Proverbs of Hell: “The most sublime act is to set another before you.”

*

Nothing has served more fruitfully as a literary inspiration throughout history as nothing itself, primarily because it is the seat of unknowing and creation itself and therefore infinitely beguiling. But from what irrational ironic source did the Judaic insight into the generative void arise? The answer to this question is less “religious” than simply imaginative and supremely literary for its inscrutable oddness that manifests in profoundly mysterious ways that endure in literature as sublime encounters with the other as Other, or as Martin Buber would say, as thou. By avoiding any reification of their deity, the authors of the Pentateuch, along with the books of the prophets, Proverbs, Job, the Psalms, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and the Gospels established unique theological conceits, particularly with regard to theodicy and their apophatic deity, that have served as foundational narratives for enduring world literature.

Unlike the cosmology of the Greeks, whose myths created an anthropomorphic literature in which its myth-makers perpetually “reinvented [their] own origins,” as Harold Bloom has noted in his book Poetry and Repression (an observation he borrowed from Gambattista Vico’s New Science), the Judaic tradition, on the other hand, featured a religious dialectic that alternated between what Soren Kierkegaard called instances of God’s “teleological suspension of the ethical,” as in the case of Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac and God’s salvific acts that were perceived as “personal” and revelatory, as in the case of His covenant with Abraham and delivery of the decalogue to Moses. Greek myth-makers, on the other hand, conceived of gods whose primary role was in maintaining the order of the universe with no particular personal regard for human concerns. This notion of divine disinterest for human life and affairs realized its cultural apotheosis in the stoicism of Zeno and Marcus Aurelius. But an ironic enigma often gets overlooked in juxtaposing Judaic revelation with Hellenistic mythology: the same God who has, in Qoholeth’s words in Ecclesiastes “set eternity in the human heart; yet so no one can fathom what God has done from beginning to end” has also interacted with his prophets and people in intensely “personal” ways. Silence and revelation alternate in diachronic reprises throughout biblical history from Job’s terrible wait for a divine response to his inexplicable suffering to Jonah’s need for an explanation from God for the reason behind his mission to Nineveh to Jesus’s last question to “Abba” on the cross: “Father, Father, why have you forsaken me?”

*

Nothing in the form of silence has played a profoundly ironic role in Western literature, especially in the post biblical era in which the absence of divine utterance and revelation, particularly in the aftermath of the Holocaust, has left only echoes of Yahweh’s voice. Heroic humor, absurdity, and nihilism have filled the void of what was once believed to be divine ventriloquism in Yahweh’s prophetic agents. Prophecy evolved into literature that didn’t always testify to the Deuteronomic code evolving ultimately into profoundly existential fiction and poetry that questioned the canonical codes of scripture—texts that were too freethinking to be considered even apocryphal. What prophet could have prophesied Brothers Karamazov, Thus Spake Zarathustra, The Heart of Darkness, Waiting for Godot, The Trial, The Fall, The Plague, The Wasteland, Fathers and Sons, Fathers and Sons, and To the Lighthouse? This shift from the post biblical, mythopoetic age to the modern era seems inevitable in retrospect as the theme and concept of theodicy increasingly captured the imaginations of philosophers and writers, inspiring them ultimately to write books like those cited above. The tropes of black humor and atheism in these texts belie any modern day credibility in the Deuteronomic code. Inherent in Judeo/Christian faith lies a divine absurdity that offers a paradoxical reason for believing in a divine Force that’s greater than the self. The church father, Tertullian, was prophetic about Modernism, Post-modernism and Post Post-modernism (which grows ever ominously closer to nothingness itself by the day) in the third century when he famously declared: “Credo quia absurdum” (“I believe because it is absurd.”)

*

One could argue that the most resonant admonition that has haunted the collective Western psyche over the past century and half lies in Frederick Nietzsche’s claim that “if there is no God, then anything is permitted.” Too much horror and concomitant impunity has besmirched human history to refute Nietzsche’s tautology. So, what poetic/fictive example of corrective silence resounds most profoundly across the span of the last century and a half in particular? There are several, of course, but one that serves as a profoundly timeless corrective is that of Christ’s silence at the conclusion of the fifth chapter of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov. In a “parable” that Dostoevsky calls “a poem” a duplicitous inquisitor in Seville in the time of the Inquisition promotes a counterfeit version of the Gospel that argues mankind is too weak both constitutionally and spiritually to sustain belief in a deity who deems both miracles and bread as compensatory rewards for faith. Ivan Karamazov, an agnostic at best, presents the Grand Inquisitor’s central point to his saintly brother, Alyosha, that people need bread and miracles over freedom in choosing between a religion that promises nothing in the way of miracles and bread and a religion that does. The Grand Inquisitor contradicts Christ’s call to forgo bread and miracles as necessary ingredients for faith, claiming institutional Christianity needs them as necessary “signs” and rewards for “believing.” A pusher of expedient Christianity, the Grand Inquisitor’s bastardized theology corroborates Karl Marx’s claim that religion, specifically Christianity, is “the opiate of the masses.” Alyosha, on the other hand, in true existential fashion, maintains that human freedom, onerous as it is, serves as a spiritual corrective to the Grand Inquisitor’s misprision of Christ’s criterion for true faith: a “religion” that excludes bread and miracles as necessary incentives for belief. The Grand Inquisitor in Ivan’s telling responds to Jesus with this famously cynical reply:

Thou wouldst go into the world, and art going with empty hands, with some promise of freedom which men in their simplicity and their natural unruliness cannot even understand, which they fear and dread- for nothing has ever been more insupportable for a man and a human society than freedom. But seest Thou these stones in this parched and barren wilderness? Turn them into bread, and mankind will run after Thee like a flock of sheep, grateful and obedient, though forever trembling, lest Thou withdraw Thy hand and deny them Thy bread.

Alyosha’s silence in response to his brother’s “poem,” a kiss on his lips, serves as a sounding board to the Grand Inquisitor’s casuistry in the guise and garb of orthodoxy. Ivan immediately ridicules Alyosha, quipping, “You’ve plagiarized me!” For Jesus also kisses The Grand Inquisitor at the end of his “poem.” Alyosha’s kiss, like Jesus’ kiss, testifies to the apophatic power of his sublime act. Its silence speaks exponentially louder than words as an intimate, even agapeic reply that intones “nothing” as freedom’s sacred rebuttal to the plethora of reassuring “somethings” of false religion. If Alyosha had spoken to Ivan, he no doubt would have echoed Soren Kierkegaard’s famous religious caveat: “Where all are Christians, the situation is this: to call oneself a Christian is the means whereby one secures oneself against all sorts of inconveniences and discomforts. . . . And orthodoxy flourishes in the land, no heresy, no schism, orthodoxy everywhere, the orthodoxy that consists in playing the game of Christianity.” Although both Alyosha and Ivan see through the Grand Inquisitor’s charade of “pushing” bread and miracles as lures for belief and devotion, it’s Alyosha who maintains the difficult but true faith of “going without” in the face of nothing.

*

Writing around the same time as Dostoyevsky, but a continent away, Emily Dickinson embraced the same fertile void as the fictional Alyosha in several of her unorthodox but sublime poems that dare approach divine “nothing,” none more than 378:

I saw no Way — The Heavens were stitched —

I felt the Columns close —

The Earth reversed her Hemispheres —

I touched the Universe —

And back it slid — and I alone —

A Speck upon a Ball —

Went out upon Circumference —

Beyond the Dip of Bell —

While Dickinson employs metaphorical imagery to express her imaginatively unorthodox venture to the outskirts of “Nothing,” Franz Kafka remains grounded and literal in his description of Joseph K’s end in his nihilistic novel, The Trial, in which all his persecuted protagonist can feel is shame at the end of his life. K stares into the void of his grave after being mortally wounded by his thuggish executioners. As his sight fails in his dying moment, he says to his killers, “Like a dog.” Kafka then editorializes, “It seemed as though the shame was to outlive him.” It is precisely K’s intransigent “shame” that haunts him, as if the fact of one’s mere being predicates inevitable humiliation. Nothing Joseph K can point to other than his guilt over merely existing effects any exculpatory power in his mind capable of exonerating him. K’s seemingly irrational sentence echoes John Calvin’s supralasarian theology with a fictive power that’s even more disturbing for its absurd but deeply human appeal. K dies in the vacuum of “nothing” with only his proleptic awareness that his shame will “outlive him.” So “nothing,” besides its paradoxical function as a cauldron for creation, exists as a mirror for K’s self-consciousness and shame. Such is its mimetic curse in K’s last thought.

Unlike Dickinson, K eschews any lyrical temptation in his spare prose, implying that the subject of “nothing”—his inscrutable death sentence— is less a poetic or metaphorical subject than simply a literal one which requires brutal honesty about the intrinsic self-consciousness of consciousness itself. Dickinson, a lapsed Congregationalist, largely resorted to poetry for her theological musings, as she does in 378, supplanting turgid theology and philosophy with exquisite poetry. Kafka avoids theology as a via negativa strategy for capturing his readers’ imagination with what Wallace Stevens called a “supreme fiction” whose narrative rings truer than the news itself.

It’s not hard imagining Alyosha kissing K. as well, but more out of empathy for his spiritually honest resistance to any counterfeit assurance in divine intervention than for his agapeic love for him. Alyosha and K. have “nothing” in common. As does Job, who, like both Alyosha and K, is left with the same hard reality of no prospect for bread or miracles to bolster his faith, only God’s Voice out of the whirlwind reminding him of his paltry place as a human in the infinitely larger scheme of creation by cataloging His miraculous efficacy as Creator in rhetorical questions about not only the provenance of creation but its utterly mystifying wonders. Conversely, with no such straining over a similar revelation or divine reminding, K. embraces his shame as a symptom of his human condition alone, with no supra-fictive conceits that provide divine solace. Such nothing is something in its heroic testimony to one’s human capacity for enduring and even enjoying life and its surreal adventures while it lasts.

*

The pre-requisite for believing in the truth that shuns religious language, while adopting the idea of a transpersonal self that crosses over to “the other” with selfless sympathy and divine imagination, is no less than the absurd love known as agape, which, as James Wright declares at the end of his poem “St. Judas”—“I held him in my arms for nothing”—embraces the other for “nothing” with a passion that transcends sense, reason, and self-interest. It is precisely there, in that inscrutable realm of nothing, that truth needs only silence as its most effective expression. For this reason, in the extreme sense, Midrashic hermeneutics might accurately be summarized in one sentence: Scripture is the irresistibly absurd yet sacred story of Nothing that is Everything.

*

Nothing speaks more sublimely about nothing than the muse of nothing herself who has inspired writers since Gilgamesh to write something about it. Nothing is ironically something, everything, in fact: the fertile void out of which the world was created and continues to evolve. It is the negative pole in the electrical polarity of creation. It is “the force,” as Emily Dickinson wrote to her friend, Susan Gilbert, “that renovates the world.” It is the paradoxical absence of everything in the dialectic of existence—the inscrutable depository of infinite possibilities and “the new” that’s perpetually vacuuming itself. It is, in Shakespeare’s King Lear, Cordelia’s truthful reply, “Nothing,” to her father when he requests her declaration of love. Cordelia’s “nothing” is everything in its safeguarding its genuineness. Lear’s response to his favorite daughter, “Nothing can come of nothing,” betrays his profound ignorance of the soul of nothing; for everything comes from Cordeila’s “nothing,” most notably her love’s sacred condition of demurring from forced confession, which her feeble father is tragically blind to. Cordelia reveals nothing’s inherently ironic subterfuge that conceals everything. It is that oceanic, personal address of the waves to each person who “has ears to hear,” as Walt Whitman observed at the conclusion of his poem “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking”: “

…the word up from the waves,

The word of the sweetest song and all songs,

That strong and delicious word which, creeping to my feet,

(Or like some old crone rocking the cradle, swathed in sweet garments, bending aside,

The sea whisper’d me.”

It is indeed eternity’s lover.

*

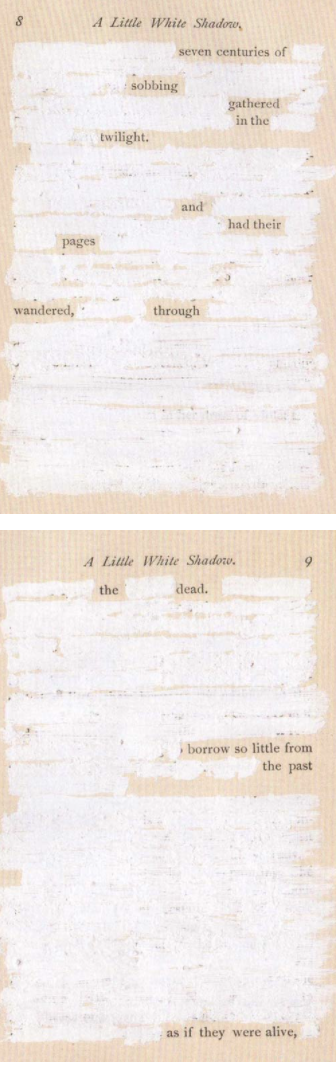

I can think of no better way to conclude this essay than by citing several examples from both secular and religious texts that betray the diachronic legacy of nothing with a universal appeal that erases any distinction between religious and secular genres. As conscious beings with the knowledge of death, how can we call literature that chronicles memorable human experience and history “meaningless,” as Qoholeth, the author of Ecclesiastes, does below in the final example of nothing’s indictment of wisdom? Such a conceit betrays the ultimate use of via negative. But John Wilmot, Samuel Beckett, Thomas Gunn, and Mark Wunderlich, Li Bai, and Mary Ruefle all add memorable commentary on this topic in their poems that are indelible for now. But John Wilmot, Samuel Beckett, Thomas Gunn, and Mark Wunderlich, Li Bai, and Mary Ruefle all add memorable commentary on this topic in their enduring poems that I have copied below–poems that add yet more “meaningless” memorable wisdom to the already overflowing canon of literature that has emanated from “nothing.”

Upon Nothing

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester

Nothing! thou elder brother even to Shade:

That hadst a being ere the world was made,

And well fixed, art alone of ending not afraid.

Ere Time and Place were, Time and Place were not,

When primitive Nothing Something straight begot;

Then all proceeded from the great united What.

Something, the general attribute of all,

Severed from thee, its sole original,

Into thy boundless self must undistinguished fall;

Yet Something did thy mighty power command,

And from fruitful Emptiness’s hand

Snatched men, beasts, birds, fire, air, and land.

Matter the wicked’st offspring of thy race,

By Form assisted, flew from thy embrace,

And rebel Light obscured thy reverend dusky face.

With Form and Matter, Time and Place did join;

Body, thy foe, with these did leagues combine

To spoil thy peaceful realm, and ruin all thy line;

But turncoat Time assists the foe in vain,

And bribed by thee, destroys their short-lived reign,

And to thy hungry womb drives back thy slaves again.

Though mysteries are barred from laic eyes,

And the divine alone with warrant pries

Into thy bosom, where truth in private lies,

Yet this of thee the wise may truly say,

Thou from the virtuous nothing dost delay,

And to be part with thee the wicked wisely pray.

Great Negative, how vainly would the wise

Inquire, define, distinguish, teach, devise,

Didst thou not stand to point their blind philosophies!

Is, or Is Not, the two great ends of Fate,

And True or False, the subject of debate,

That perfect or destroy the vast designs of state—

When they have racked the politician’s breast,

Within thy Bosom most securely rest,

And when reduced to thee, are least unsafe and best.

But Nothing, why does Something still permit

That sacred monarchs should at council sit

With persons highly thought at best for nothing fit,

While weighty Something modestly abstains

From princes’ coffers, and from statemen’s brains,

And Nothing there like stately Nothing reigns?

Nothing! who dwell’st with fools in grave disguise

For whom they reverend shapes and forms devise,

Lawn sleeves, and furs, and gowns, when they like thee look wise:

French truth, Dutch prowess, British policy,

Hibernian learning, Scotch civility,

Spaniards’ dispatch, Danes’ wit are mainly seen in thee.

The great man’s gratitude to his best friend,

Kings’ promises, whores’ vows—towards thee may bend,

Flow swiftly into thee, and in thee ever end.

From Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett:

ESTRAGON:

What do you expect, you always wait till the last moment.

VLADIMIR:

(musingly). The last moment . . . (He meditates.) Hope deferred maketh the

something sick, who said that?

ESTRAGON:

Why don’t you help me?

VLADIMIR:

Sometimes I feel it coming all the same. Then I go all queer. (He takes off his

hat, peers inside it, feels about inside it, shakes it, puts it on again.) How shall I

say? Relieved and at the same time . . . (he searches for the word) . . . appalled.

(With emphasis.) AP-PALLED. (He takes off his hat again, peers inside it.) Funny.

(He knocks on the crown as though to dislodge a foreign body, peers into it again,

puts it on again.) Nothing to be done. (Estragon with a supreme effort succeeds in

pulling off his boot. He peers inside it, feels about inside it, turns it upside down,

shakes it, looks on the ground to see if anything has fallen out, finds nothing, feels

inside it again, staring sightlessly before him.) Well?

ESTRAGON: Nothing.

VLADIMIR: Show me.

ESTRAGON: There’s nothing to show.

The Annihilation of Nothing

Thomas Gunn

Nothing remained: Nothing, the wanton name

That nightly I rehearsed till led away

To a dark sleep, or sleep that held one dream.

In this a huge contagious absence lay,

More space than space, over the cloud and slime,

Defined but by the encroachments of its sway.

Stripped to indifference at the turns of time,

Whose end I knew, I woke without desire,

And welcomed zero as a paradigm.

But now it breaks—images burst with fire

Into the quiet sphere where I have bided,

Showing the landscape holding yet entire:

The power that I envisaged, that presided

Ultimate in its abstract devastations,

Is merely change, the atoms it divided

Complete, in ignorance, new combinations.

Only an infinite finitude I see

In those peculiar lovely variations.

It is despair that nothing cannot be

Flares in the mind and leaves a smoky mark

Of dread.

Look upward. Neither firm nor free,

Purposeless matter hovers in the dark.

The God of Nothingness

Mark Wunderlich

My father fell from the boat.

His balance had been poor for some time.

He had gone out in the boat with his dog

hunting ducks in a marsh near Trempealeau, Wisconsin.

No one else was near

save the wiry farmer scraping the gutters in the cow barn

who was deaf in one ear from years of machines—

and he was half a mile away.

My father fell from the boat

and the water pulled up around him, filled

his waders and this drew him down.

He descended into water the color of weak coffee.

The dog went into the water too,

thinking perhaps this was a game.

I must correct myself—dogs do not think as we do—

they react, and the dog reacted by swimming

around my father’s head. This is not a reassuring story

about a dog signaling for help by barking,

or, how by licking my father’s face, encouraged him

to hold on. The dog eventually tired and went ashore

to sniff through the grass, enjoy his new freedom

from the attentions of his master,

indifferent to my father’s plight.

The water was cold, I know that,

and my father has always chilled easily.

That he was cold is a certainty, though

I have never asked him about this event.

I do not know how he got out of the water.

I believe the farmer went looking for him

after my mother called in distress, and then drove

to the farm after my father did not return home.

My mother told me of this event in a hushed voice,

cupping her hand over the phone and interjecting

cheerful non sequiturs so as not to be overheard.

To admit my father’s infirmity

would bring down the wrath of the God of Nothingness

who listens for a tremulous voice and comes rushing in

to sweep away the weak with icy, unloving breath.

But that god was called years before

during which time he planted a kernel in my father’s brain

which grew, freezing his tongue,

robbing him of his equilibrium.

The god was there when he fell from the boat,

whispering from the warren of my father’s brain,

and it was there when my mother, noting the time,

knew that something was amiss. This god is a cold god,

a hungry god, selfish and with poor sight.

This god has the head of a dog.

From Ecclesiastes:

The words of the Teacher,[a] son of David, king in Jerusalem:

2 “Meaningless! Meaningless!”

says the Teacher.

“Utterly meaningless!

Everything is meaningless.”

3 What do people gain from all their labors

at which they toil under the sun?

4 Generations come and generations go,

but the earth remains forever.

5 The sun rises and the sun sets,

and hurries back to where it rises.

6 The wind blows to the south

and turns to the north;

round and round it goes,

ever returning on its course.

7 All streams flow into the sea,

yet the sea is never full.

To the place the streams come from,

there they return again.

8 All things are wearisome,

more than one can say.

The eye never has enough of seeing,

nor the ear its fill of hearing.

9 What has been will be again,

what has been done will be done again;

there is nothing new under the sun.

10 Is there anything of which one can say,

“Look! This is something new”?

It was here already, long ago;

it was here before our time.

11 No one remembers the former generations,

and even those yet to come

will not be remembered

by those who follow them.

Zazen on Ching-t’ing Mountain

By Li Bai

Translated by Sam Hamill

The birds have vanished down the sky.

Now the last cloud drains away.

We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.