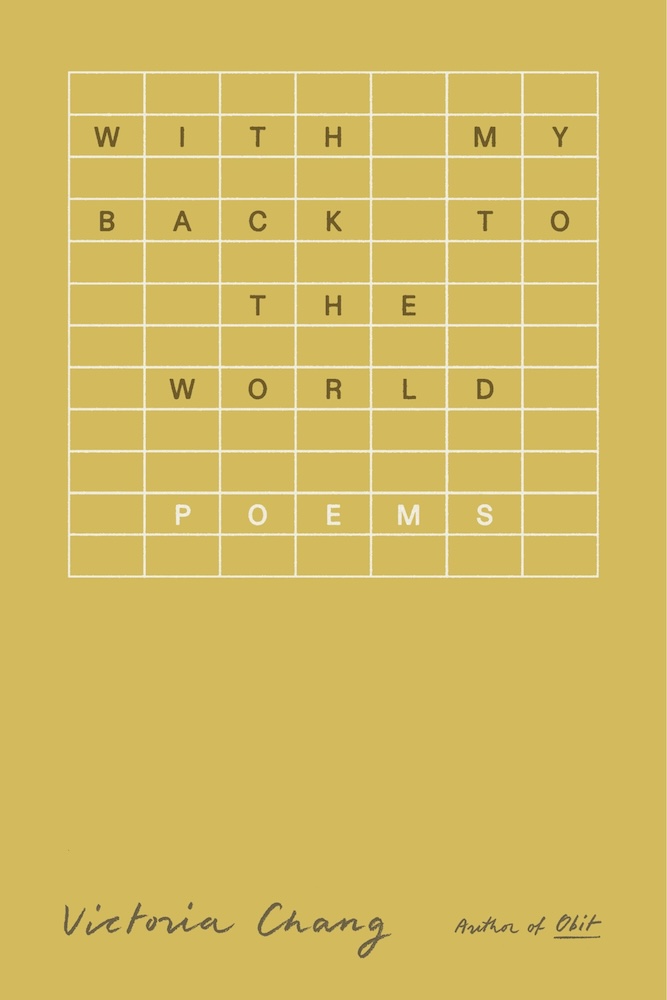

Victoria Chang’s With My Back to the World reviewed by Linda Mills Woolsey

With My Back to the World

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024

ISBN: 978-0-374-61113-2

Victoria Chang’s With My Back to the World is a stunning book that merges fiercely disciplined form with wild thought and mordant wit. Readers of Chang’s work from Salvinia Molesta (2008) to OBIT (2020) and The Trees Witness Everything (2022) will catch glimpses of her persistent themes held to a new light. Like shot silk, the translucent language of this densely interwoven text shimmers with new colors in the light of each rereading.

The poems in With My Back to the World take their often-ironic titles from paintings by Agnes Martin and On Karawa, but they push the boundaries of the ekphrastic as Chang both looks at and beyond the paintings to probe larger themes: artistic aspiration, depression, loss, inhabiting time, and being a woman in a violent and beautiful world. Chang finds Martin, who died in 2004, a mentor, antagonist, model, and alter ego. In “Falling Blue, 1963,” Chang observes:

Someone wrote that Agnes made small simple repetitive

gestures that led to something larger. This resembles a life,

each day a mark on a canvas. Or the way a prisoner might

carve each day into a wall.

This collection often looks at the ways art (and poetry) can “mark” time–recording experience, organizing it into grids, counting breaths. Yet they also probe the way brushstrokes and words escape time’s prison, defying chronology and persisting when the artist has died. Thus, like Martin’s paintings, these poems demonstrate how small gestures of language can accumulate to powerful effect.

Testing the possibilities of language, Chang stipples poems with small gestures–playful slippages of meaning and deft line breaks to keep the reader off-balance. Here, non-sequiturs create hairpin turns of imagination and blocks of text are mined with small explosions of syllogistic thought. In “Untitled #5, 1998,” Chang writes: “Maybe every poem is an // attempt to describe lightning. Maybe lighting can’t be described / which is why there are so many poems.” Maybe. And in With My Back to the World, as words accumulate, felt experience flashes before us in moving glimpses shadowed by mortality.

This book invites us into an intense awareness of life itself. While language can never capture our lives fully, it can remind us to be fully present to them. Chang knows that we resist this.

While we have a name for everything—even our dying breaths—we find some things unsayable or choose to let them remain unsaid. This is clear in the book’s central section, “Today.” Like Obit, “Today” deals with the death of a parent—this time, a father. Here, instead of death notices, Chang gathers dated daily verse entries under a title borrowed from On Karawa’s famous series.

“Today” recounts a daughter’s response to her father’s dying and registers the ways we avoid naming the things we dread or love. When the hospital calls with the news of his death, they don’t use the words “death or died” (“Jan 23, 2022”). Counting her father’s Cheyne-Stokes breaths, the daughter says:

I can hear all the words said in your

life, now in a different order. There’s still

no love, even though I’ve looked through all the

words twice. I go digging in the mass grave

of language for the extra loves and I

end up bringing loneliness back with me. (“Jan. 18. 2022”)

As in Obit, mortality infects language, which has its own murderous possibilities: “If I keep the window closed, I am stuck / inside with language as it buzzes back / and forth, trying to get out and start wars” (“Feb 14.2022”). Here, Emily Dickinson’s fly has become a swarm of words armed like hornets, and escape feels more deadly than freeing.

If words have the power to make war, they can also be shaped into commodities that deny or disguise danger. In this collection, language participates in a commerce where everything from tears to moonlight is for sale. In “Homage to Life, 2003,” Chang declares, “Everything violent in the / world can be made beautiful with language. Someone / passes, departs, or succumbs. This is called advertising.”

Even when we resist commerce by turning our backs to the world, the world is always touching us, roughly or gently and our “now” is studded with losses. In “The Beach, 1964” we see that the

pumping force of the heart should have told us that life is a struggle

in one direction, and the letdown of an endless loop, as we wait for

the loop to be cut like a ribbon.

Seeking permanence, art both reinforces and resists this loop, just as it participates in both its perpetuation and its cutting. But for all our art, the poet insists that we can’t escape time—the year of a book’s writing, the months of depression, the day of a death.

Martin, given the tyranny of time, offers strategies for control and freedom that Chang tests in her own work. But repetitions of “Agnes says” are countered by the speaker’s “what if” or “I want to ask.” In Martin’s world, penciled grids hold emotions, apples become rectangles, and where red paint drips like tears or menstrual blood, it does so in defined bands. As Chang steps close or zooms out, though, the paintings merge with the language of feeling.

In “Happy Holiday, 1999,” Chang ponders Agnes’s description of squares as “overconfident and aggressive” while rectangles are “more relaxed / softer, and agreeable.” This prompts her speaker to declare: “The pain I feel inside my chest is a heart’s / change from a square to a rectangle. The stretching hurts.” Feelings may be organized or reshaped on canvas or in a poem, but the pain of living persists.

Even so, as Chang arranges phrases in homage to Martin’s grids, bands, and blocks of color, prose stanzas cease to be rooms and become geometric forms hung on the page. The poet reinforces the poem-as-shape, as aesthetic object, by setting poems against facing pages where typescripts of the poem become illustrations—inked over with bands, hatch marks, and scrawls. Some poems-as-paintings look like censored texts, some like palimpsests. My favorite is “Untitled #5, 1977,” blacked out except for small white holes through which typescript letters peer. All of these poems, though, hint at the incompleteness of our artistic gestures, their excesses and absences pointing to life itself, always eluding our grasp.

Whether it’s the death of a parent or a planet, Chang translates life into art knowing that things will be lost in that migration to a world where “sadness and language cast the same shadow” (“Untitled # 10, 2002”) but where “in every language, the heart can be in pain” (“Summer, 1964”). Martin models withdrawal, solitude, and a quest for “emptiness” in response to that pain. For her, turning one’s back to the world is an either/or proposition. But Chang writes toward a both/and stance:

Now I think that death is the form

of love. My real secret isn’t that I have two hearts, but

that I have two eye colors. My blue eye can see death and

my brown eye can see love. The trouble is that looking

involves both eyes. (“Untitled, 1960”).

Looking is central to these poems as Chang explores strategies for making these two eyes one in sight.

As she does this, Chang confronts tensions between artistic solitude and the craving for an audience. Her solitude takes selfies and posts them (“Grass, 1967”) and when she has her depression “reorganized into grids,” she finds that “Once I write the word depression, it is no / longer my feeling. It is now on view for others to walk / toward lean in and peer at.” Here, the whole project dissolves. Staring at a painting “all morning” she begins to question its colors and lines and finds that depression “on view / isn’t actually on a canvas at all but is in the air and / illegible” (“Play, 1966”). Feeling has, once again, escaped from what would contain it.

Yet—skillfully balancing serious questions, surreal imagery, and playful humor—the poems render feeling visible and legible. The speaker can sling depression on her back and take it into the museum. Or leave it outside in a picnic basket so ants can “cut up my depression, lift it away to feed a queen” (“Leaves, 1966”). It swarms back, the powerful “CEO / of feeling. All other feelings are direct reports.” (“Happiness from Innocent Love series, 1999”).

In “Leaves, 1966,” as depression “regrows each night,” it “resembles leaves. But everything / resembles leaves at some point,” even human beings. “Language isn’t actually inside us as I had thought. We / are tenants of language. We are leaving while writing.” Like the poem’s leaves, we mortals are subject to “arrival and decay,” our language unfurling in quarrels and poems, marking our brief presence in the world.

Facing our mortality, Chang suggests that “Maybe a life doesn’t matter so much as the / feeling it leaves behind, whether anyone receives / the feeling or not. Maybe our goal is to spend all the / light.” (“Untitled #9, 1995”). Art, in other words, becomes less about containing light than casting light. Aware that “there is no first draft of a life” (“On a Clear Day”), Chang spends her own light with gusto in poems still “trying / to pin language to the sky,” though “only language is the one that gets to stay” (Untitled #5, 1998).