Mackenzie Kozak

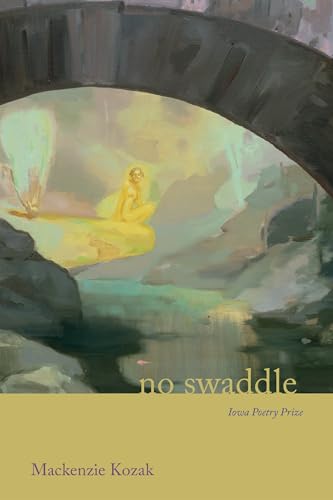

No swaddle

University of Iowa Press, 4.10.2025

Reviewed by Celeste Lipkes

An identity defined by lack is only interesting if everyone presumes its opposite is essential. As a 35-year-old woman, I spend a lot of time reflecting on why I am childfree and no time at all wondering why I am not an NFL coach or a nun. When people inevitably ask why I don’t plan to have children, I tell them whatever I believe will most efficiently conclude the conversation. Despite ruminating for years about parenthood, my explanations compact into Pew Research Center approved responses: “Concerns about the state of the world,” “Can’t afford to raise a child,” and the vague trump card “I just don’t want to.” To convey a more complex ambivalence about parenthood is to risk offense or unwanted advice, but when it comes to essential questions about how we want to inhabit our lives, there is a cost to flattening our answers. So it seems a worthwhile goal to elbow out space for more nuance—if not in surveys, then perhaps in literature.

Mackenzie Kozak’s debut poetry collection, no swaddle (University of Iowa Press, 2025), considers the complex question of bearing children through a series of sonnets. The book is framed by an epigraph from Sheila Heti’s Motherhood, a sharply perceptive and at times frustrating work of autofiction in which a Heti-like narrator engages in a 300-page self-interrogation: “Whether I want kids is a secret I keep from myself—it is the greatest secret I keep from myself.” Kozak’s speaker is Kozak-like in age and gender, though the largest clue of their near-overlap is in the book’s acknowledgements, where Kozak thanks her therapist who “witnessed my process of grappling with the questions addressed in this collection.” no swaddle probes the same greatest secret as Motherhood, but Kozak’s methodology is less self-cross-examination and more therapeutic curiosity (Kozak is, herself, a grief therapist). Still, the books mirror each other in many ways; in an interview with “Debutiful,” Kozak notes that she could not have written her book without Heti’s. It will be useful, then, to occasionally put them side by side.

Motherhood and no swaddle understand that what we want for ourselves is difficult to sieve from the soup of what others desire for us. Heti and Kozak both attempt to clarify their individual yearnings in a world that waits expectantly for them to have children (as Kozak observes: “a woman inflates to the sound of applause”). While Heti grapples with whether she wants to be applauded for making books or making babies, Kozak is less concerned with the question of artist-as-mother. She fixates instead on the pressure of lineage:

…if my mother’s mother

had not, then what would not be?

which is also the question of cattle or sheep,

wanting to fill the pen. every day became

a roving tangle of lines, and everyone

asked me to draw the line forward

over an edge.

Expectations about what women should carry forward appear throughout the book in images of lines, cords, and threads being caught, frayed, and severed—sometimes violently (“choking the throat of the lineage”).

The pressures men place on women to carry on the family line are incessant and predictable; these arguments are mostly ignored by Kozak in lieu of exploring the influence women have on one another. Some of the most memorable sonnets in Kozak’s collection feature a recurring character, “a woman i know who is part-mother,” who says things like: “if he is a good man, you should make more / of him.” (The part-mother does not elucidate what we should do with a good woman—presumably impregnate her.) While various “him”s and male “you”s of unknown origin float throughout Kozak’s poems, only women are named. Many of the poems in no swaddle are addressed to the speaker’s mother or sister; others feature the aforementioned part-mother or the speaker’s hypothetical future child—always female, sometimes named Lucy.

When Kozak’s speaker encounters females out in the world, we see some of the real stakes of remaining childfree: separation from the women she loves. She asks a woman who is part-mother, looking down at her infant daughter: “when you see her can you see yourself. . .will you see me, if I do not follow suit?” When mothering is allowed to define womanhood, suspicion and judgment flow insidiously and bi-directionally between mothers and women who choose not to have children. no swaddle astutely draws our attention to this secondary grief, the rupture of the speaker’s “dream that we might / all remain daughters.”

To get their arms around the question of parenthood, both Motherhood and no swaddle rely on constraining formal structures: Heti’s book uses sections of text to ask a series of questions about having children. The speaker then flips three coins to determine each answer—a technique inspired by the I Ching. In no swaddle, Kozak writes solely in what she calls “American sonnets,” all of which are, by their definition, unrhymed and unconcerned with meter. Kozak’s sonnets are additionally distinguished by being untitled, compacted into one stanza, and without any capitalization. They twice gesture at the conventions of a sonnet crown—the second poem ends with “in a bed / made of wind and womb.” which is then picked up in the third sonnet’s first line—but otherwise can be read as discrete entities, without a common “you” and concluding with a satisfying click on an image or a question. I imagine these structural restrictions were essential to the initial production of both projects. But, once written, it is less clear if these formal limitations remain necessary to the reading.

Like the cramped binary of Heti’s coin flip, there is something usefully claustrophobic about Kozak’s sonnets; we feel trapped in the same question alongside her, pacing the same four walls. Everyone’s favorite Introduction to Poetry fact—that “stanza” comes from the Italian for “room”—becomes relevant, as Kozak uses the single room of each sonnet to explore living in rooms with and without children. In just the first ten sonnets, we encounter references to rooms five times, including “a room without babbling” and the speaker struggling to “invent a story where / i carry the doll from room to room, pausing there, there, with the palm.” It’s also possible that Kozak felt the form itself might be instructive; as Diane Seuss writes in her own sonnet, “The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without.”

But—as Heti knows—there is a flipside to every coin: reading sixty nearly identical looking sonnets in a row naturally invites the reader to compare them. And looking closer at no swaddle, it becomes clear that the sonnet form is not serving every poem individually. In some of Kozak’s poems, her descriptions stack precariously high, sticky with the glue of commas and conjunctions, until we can no longer see what is being said:

i came to you cathedral-mouthed,

a darkened-glass silence to me,

and dug you a theater, a calm dream,

and drank the dredges before a flock

in lit rooms, and guessed at harbors,

concealed them, and came to something

like a swarm, gave reverence to it,

made discourse of it, and wore a robe

that floated as a spirit through the bleating

halls. you gave me heft and gravity,

no float to me, no height or heat,

no wax dripping, no stair to stand from,

and permitted me a rambling row,

to walk down, to warble.

There is a wispy imprecision to Kozak’s language here—images are sketched so loosely and modified so briskly that little is ultimately visible. It is unclear how a dug theater is a calm dream, if the flock is a congregation that then bleats as God’s metonymic sheep in the form of a hallway, or what, exactly, is swarming. I do not understand literally or metaphorically how the gift of gravity affects either height or heat. In a review of Elizabeth Bishop, Michael Hofmann writes that a Bishop poem “goes on looking long after one thinks it should have looked away.” In the less successful poems in this collection, Kozak’s eyes flit all over the place. This effect is compounded—or perhaps even created—by the formal constraints she places on her project. Every poem is crammed into 14 lines, and capitalization, a wider range of punctuation, and space such as stanza breaks are not available to clarify how images relate with any logic to one another. Kozak is plenty capable of giving us clear and compellingly rendered things to look at—in one poem, the smooshed cheek of a baby on a monitor is “reminiscent of blair witch”—and it is frustrating when she refuses to do so. Poems, like women, should be both seen and heard. The most effective individual sonnets in this collection do not run solely on a sonic motor or eschew images for mere impressions.

If Phillis Levin can define a sonnet in The Penguin Book of the Sonnet as a poem that makes “a series of sonnetlike maneuvers,” then I can make an equally tautological claim that a long poem is one that behaves like a long poem. And the more I sit with no swaddle, the more I think of it as a long poem and not solely an assemblage of sonnets. Despite its refusal to subvert its initial formal restrictions, it has many of the other trappings of a contemporary long poem: it is highly self-referential (halfway through the book: “i must, as i always do, think about / the ending”); it stretches a reader’s patience in both its length and the capaciousness of its interrogation; it is ambitious and messy. Most importantly, the shape of a long poem allows a poet to change her mind. Near the end of Motherhood, Heti’s speaker reflects on the length of time she needed to make a decision about having children: “I felt obliged to consider it—to consider it until the very last second—before finally turning away.” For Kozak’s speaker, deciding ultimately not to have children is a prolonged exercise in unimagining. After years of sitting alone and with her partner, across from women who are part-mothers, sisters, and therapists, she recognizes that to choose any path is to grieve the alternative future that will never exist. In the last set of sonnets in no swaddle, the speaker says goodbye to hearing a roomful of babbling, to seeing her partner’s “burnt amber hair” on the head of a child. She ultimately decides not to have children by mourning not having them. By positioning her project between love poem and elegy, between sonnet series and long poem, Kozak models the difficult work of being able to sit, at length, with both ambivalence and grief; if I wanted a daughter, this is what I would want for her.