WHAT IF THE INVADER IS BEAUTIFUL

Mystic in the Mojave, Louise Mathias

in Conversation with Nancy Mitchell

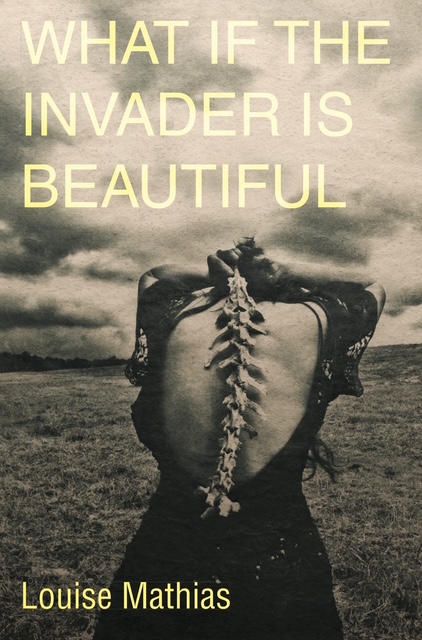

NM: I don’t think I’ve read a book of poems in the past year as intriguing as your stunning new WHAT IF THE INVADER IS BEAUTIFUL. (Four Way Books, 2024) The eerily surreal cover and the singularly existential title question alert us that we are entering an alien, liminal landscape in which the speaker and the question will square off, the resolution of which informs the arc of the book. How much does the Mojave Desert, the liminal space in which you dwell, inform these poems? Could they have been written in any other landscape?

LM: It informs the vast majority of them deeply—the land itself, the flora and fauna, the lonely roads, the love I’ve found myself in, the intense reckoning with the past I’ve done since moving here, the overwhelming beauty of it all, the brutality of 108 degree summers, it’s all inextricably connected and impossible for me to un-tangle. I’m deeply interested in how our relationship with the natural world affects us, and this is the ecosystem I primarily inhabit, that inhabits me, so here we are. There are a handful of poems in the collection that were written in or about other landscapes (prairies, coasts) but they were written by me, a long-term creature of the Mojave, so the desert informs those as well I think, in that living here has changed my inner world and the closeness and intensity with which I regard other landscapes.

NM: What was your initial encounter with the desert and why did you stay?

LM: The first time I came to the Mojave was back in 2006. It was during a time of some psychological duress though I can’t recall the specifics, and that trip very much had the quality of escape, an attempt to get out of myself, or get back into myself, I’m not sure. The spaciousness of the landscape, the quality of the light, that’s what I remember most—and as I was driving back to LA from a too short weekend, I remember having a radically clear vision of a future as an elderly woman where I lived out there in a remote little house, likely alone, free from societal expectations, all that. At the time I had a 9-5 where I had to go into the office every day, so it seemed a dream for a distant future.

NM: That vision! I hear Rilke’s What seems so far from you is most your own. What you perceived as distant was near; your future self, the elderly woman, called you to her and the desert; what you were longing for was longing for you.

LM: It definitely felt that way, like a calling. A couple of years later I ended up transitioning to remote consulting for work and so was able to spend more time out here, and then an opportunity to rent a place long term was presented to me, and eventually I bought a little house. It was a leap of faith as I really didn’t know a soul, and at that time Joshua Tree didn’t quite have the large creative community it is known for these days. But I knew how I felt here, and I knew I would find much joy and wasn’t afraid of the solitude—welcomed it. Why I’ve stayed is that it’s the one place I’ve ever lived where I felt my inner landscape and outer landscape deeply “match”, if that makes sense. I’m just at home here, and while I could try to intellectualize why, it’s more just the way my body feels than anything.

NM: This “match” puts me in mind of Gaston Bachelard’s poetic reveries, which take place in timeless liminal landscapes accessed through willed, solitary contemplation of natural phenomena. In deep, sustained, reveries, the observer is “rid of their history, of their name,” and the observer and the observed interpenetrate. It’s in this fusion that an original poetic image arises and gives rise to more original images, which become lyric poems such as the ones in this book. To my mind/eye/ear the poems in the book mirror this process in couplets and tercets separated by the charged white liminal space of the desert, which give rise to startlingly original and vivid imagery such as Shame is a dove//her soft side/filled with maggots (Dom)

LM: Yes, and I often think of the white space in my poems as breathing room, in part I think it’s sorely needed because there is often a kind of intensity or even volatility to the what is being expressed that needs space to have full impact– it slows it down a bit– gives it room to breathe, allows what hidden to become clear, and yes, that is much what the desert, or really any very open landscape also does for me.

NM: I wonder if it’s the only space vast enough, in proportion to the space the trauma and struggle take up in the body.

LM: That resonates for me. It has been the site of healing for me, and of course, the desert has long attracted seekers of various kinds.

NM: Yes, universally, and for millennia, mystics, saints, artists, writers have come to the desert seeking solitude and privacy to work, as Agnes Martin wrote, with my back to the world, are fully transformed in the process.

LM: Fifteen years here has changed me from the inside out. You can’t hide from yourself here, you are simply faced with yourself and have to reckon. And when you strip the trappings of civilization back a bit, when there is more space, you have the land itself to keep you company—if you are open to it, it can be a deeply elemental existence out here. I think that people tend to think of the desert as being a landscape of nothing, when in fact, the opposite is true, if you look closely – it’s thriving with life and weather systems and beauty that somehow seems to shine even more brightly than it does for me in other places. But it’s also a place where the elements can be deeply dangerous and is inhabited by dangerous creatures– life and death seem more closely intertwined here than they do in many places, and I’ll confess I’m attracted to that, a kind of ongoing battle between Eros and Thanatos.

NM: Ultimately, isn’t this the primal archetypal battle, and the liminal space between the beginning, Eros, and the end, Thanatos, where the battle is waged?

LM: Indeed—and I suppose has always been my primary subject matter but seems more at the forefront in this newer book than my previous work, I think.

NM: The arc of the book seems to track the stages of the journey to wholeness: ONE, Willed Solitude/Separation; TWO, The Trial; THREE: Transformation/Integration, which I’ve briefly delineated with poems from each stage below. In a stunning arrangement, the title poem What if the Invader is Beautiful opens the third section of the book, following the second section in which the speaker has endured the arduous, archetypal trial of facing and reckoning with the self: Reached by summer, /and unafraid of after (Sylvan Instance), and is on the threshold of transformation. It’s in the tension between the question and the answer that the speaker is suspended. Maybe—and I say maybe because I don’t want to presume—it’s by acceptance of this suspension, Keat’s Negative Capability, Rilke’s Live the questions that entrance is granted. Can you speak to this and tell us more about the title?

LM: I often aim for titles that illuminate the work somehow while at the same time deepening the mystery, which is what I hope I’ve accomplished with this one. In simplest terms, it’s a reference to an invasive tree (the tamarisk) that grows in the Mojave and is both destructive to the ecosystem while also beautiful in bloom. That co-existence of beauty and harm and how to ultimately live in equanimity with this paradox is one of the central themes of the book. I’m still working on that, of course, it’s a lifelong endeavor. For so long, though, my ideas around romantic love, for example, were fixed in that I believed, consciously or not, that all that passionate love came with a price and that price meant enduring things that were harmful to me. Untangling and moving through that to the other side, where I no longer believe love and harm to be inevitably entwined, is the arc towards healing that you are picking up on. I want to distinguish here between harm and loss, because all love ends in loss one way or another. But in the end it’s kind of an unanswerable, perhaps even moot question, which is why I chose to omit the question mark—for me the title hovers somewhere between question and statement in that on the one hand it’s a given that terror and beauty often do live in close proximity, but on the other hand, one can engage with these concepts artistically and philosophically without being fated to enact them at one’s own peril.

NM: Louise, WHAT IF THE INVADER IS BEAUTIFUL is nothing less than a tour de force. Spending the summer with it has been awe-inspiring, revelatory, and enriching beyond measure. I turn to it again for refuge from and hope for this batshit inside-out, upside-down world. Thank you for your time, thoughtful, generous responses, and graciousness in agreeing to record audios of your poems, as well as share a few photos of your beloved Mojave with Plume.

Dear Readers, since I know you’ll want to own this book and hold it in your hands, I’ve included a link where you can purchase it.

Thank you, thank you, Louise. Keep your light burning in the desert for we wayfaring seekers.

ONE

Three Types of Mimicry

I pictured butterflies each time the boy was hurting me.

I say boy, though he was north of forty. I say hurt, because for years

I spoke in pretty code. There are no butterflies on Mars,

and here on earth, Mohavea

confertiflora dupes the bees because she has to—

as when I told the boy he made me come

because the other path was frozen lakes and crosshairs.

What color are my eyes? I asked his back

a dense arithmetic of bramble, fear and birdsong.

Doomsway

More strange than the way music matters,

is the fact that these flowers rage on

pursuing of storm, long after

the split ends of summer, rosy boas

can mate all day—

hearts growing larger with conjure.

Some say the tree seduced the axe.

My anger he said

looking right in my face

is global.

Dom

In a country where roses grew well, I lost it all.

My will to be

his glittering acquisition. What stars are for.

Dopamine/synapse,

history/fail.

Someday, I’ll call this what it is.

Shame is a dove

her soft side

filled with maggots.

Eidolon

Washed my hair

in the kitchen sink. Humans

hadn’t seem me in a while. This was the fall

into Spring

when I would not

listen to music.

Music like vapor from horses,

it could not exist.

Vapor from horses,

now playing in room #9—

Almost I think that I loved him

the way he took photos,

I didn’t seem there.

Another

mauled river

I did not snap

my neck in.

TWO

Lorazepam

Our contract was balletic—

you took from me

the rabbits spooked

inside their still-damp nest.

Then, you were a room I lived through,

entirely. Snowed in

all the way up to my guilt.

“One form of heaven is nothing.”

Ignorable now, the gnaw

a highway’s plaintive hiss.

Sylvan Distance

Come over.

Help me bury that

where-do-I bury-the-body look.

And the bullshit tree I was born in.

While your eyes were closed, it snowed, but only vaguely.

Reminds me of a breast a friend described,

so white it held the world up for a time.

This drag I take to stave off loss.

It’s winter now, your hair the color of cornfields

behind my childhood house

where we all rehearsed our cruelty.

And the Eastern Sierra hills

where I slipped

out of the rope that held me.

Girl wrapped around a steering wheel,

girl strung from a tree.

Reached by summer

and unafraid of after.

Temblor Range

So what if you thought that you knew me?

In the shadow of oilfields

bruised sea of scorpion weed, the land beyond

exhausted—.

The first time I thought of death

as a place that might help, I was only a child.

Later, I knelt for you, knowing that it wouldn’t.

Some said I needed God; in the soft light

and dreaming of atrocity, I took each snow-colored pill

the way I was told.

I could live here, I thought.

Only one tree in the whole of the valley.

THREE

What if the Invader is Beautiful

In the tallgrass

where all gold starts

wind became

my additional lover.

His hand the inflorescence

one finger partially gone—

Lovegrass/

Panicgrass/

Witchgrass./

**

I carefully researched

how to bait my trap.

Took the small blonde charmer

out of town.

Stealer of cholla,

eater of sun-murdered plants.

I knew it would die coming back.

**

Ajo lilies

now up to my waist.

What blackened

the opal knowledge—

What his ghost finger traced.

Rangelands

The river curved

informed by something ancient.

A vital wound

drawn out between swept hills.

I could die out here tonight

owning nothing

but the knowledge that ravens will find me.

Doomed cattle out to the West.

Doomed in the hands

of the occupant grasses.

But the sky all church again.

Lucky

Dusk in the rift-valley now, saffroning.

Wild Horses

reduced to spindle

skeletal trees—

The chestnut one barely an existence.

In the grimly lit adobe,

Amargosa

he holds me

like a storm-charm.

This is not

what I thought it would be.

Louise Mathias was born in Bedford, England, and grew up in England and Los Angeles. She is the author of two full-length collections of poetry, Lark Apprentice (Winner of the New Issues Poetry Prize) and The Traps (Four Way Books), as well as a chapbook, Above All Else, the Trembling Resembles a Forest, which won the Burnside Review Chapbook Contest. For the past fifteen years, she has resided in Joshua Tree, California.

https://fourwaybooks.com/site/louisemathias/