Of Mountains, and Bird’s Nest Soup, and Charles Lindberg

Someplace in my life, in the back of my mind where there’s a small kitchen, I began to notice similarities between names of Chinese paintings and names on Chinese menus. Here are some of these actual names:

Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains

Seafood with Bird’s Nest

Loquats and a Mountain Bird

Crossing the Bridge Noodles

Wooded Mountains at Dusk

Buddha Jumps Over the Wall

Ten Thousand Li Along the Yangzi River

Such combinations! The similarities of names and titles evoked for me both the spaciousness of Chinese landscape paintings and the specific tastes of Chinese restaurant food. In turn, they called forth the kind of “Crazy Zen” sensibility (I’ve been a Buddhist for over fifty years) that jumps randomly from the general to the specific or from sense to nonsense and then, usually but not always, back again.

How does one catch in the same poem the scent of a dumpling-filled soup, mist hovering over a computer screen, the feeling of chopsticks between one’s fingers, and of how an admonition by a noted bodhisattva can fit side by side with the lyrics of a Simon and Garfunkle song?

* * *

I’ve written about a hundred of what I’m calling “The Chinese Menu Poems.” Sometimes the poems have been evoked by names of entrees and ingredients from Chinese menus I’ve collected during travels around America. Sometimes they evolve from a Chinese painting I’ve seen in a museum or found reproduced in a library book. But just as often the poem has come before its title and the title is added to tap into the mood or tone of the poem.

What I hope these poems with their unusual titles might always do is merge Eastern and Western sensibilities. In a technology-battered age, increasingly there may be the need simply to see a maple leaf floating in still waters—to really see, as mindfulness mavens and Zen Masters would have us do. Conversely, to ignore a fighter jet screaming above us as we walk down a lonesome highway is to deny the present.

* * *

In the 1960s, I was briefly the Teaching Assistant of poet John Berryman

during a year he spent as guest faculty at Brown University. At that time, Berryman was most excited about what he called “leaping” in poetry. A word, a phrase, an image appears in a poem and its appearance creates a leaping-off place. This leap is most usually associative. “Ocean” may lead to “whale” which leads to Moby Dick, which leads to the image of a man’s arms hanging onto a floating coffin.

However, another kind of leap may be a disconnected one or a disconcerted or even surrealistic one. In this case, “ocean” may lead to “fried rice” which leads to “children’s playground” which leads to the lid on a coffee cup in Missouri.

The latter kind of “leaping,” it struck me many years later, does not have to be given the psychological tying into “the deep image” Robert Bly made famous. In the East, it’s most akin to Zen, to the unexplainable-in-words leap a disciple must make in order to solve a koan.

Or it’s akin to how the artist lets the hand painting an enso feel when it’s time to lift the brush from the paper. . . now! . . . a moment before the enso swirl is completed.

* * *

So, in my Chinese Menu Poems, I’m hoping I might set before the reader a grasshopper leap or two, a small bowl of soup that contains vegetables and maybe a piece of shrimp and perhaps an insubordinate mosquito. If landscape dominates in a poem, maybe the reader will be able to slurp some noodles or hear part of a verse from the Tao. It will go without saying that I like poems to be small experiences in and of themselves rather than operate by narcissistically delving into the individual poet’s psyche—poems when a fish may unexpectedly lunge upwards from a pond, a momentary snow slide begins, a life unaccountably reverses itself.

* * *

Thus, the titles of each Chinese Menu poem, if they work, are meant simultaneously to relax the reader and prepare the reader for something off-kilter containing delight or fear or a bittersweet taste.

In Zen, you may be walking down an unfamiliar street, as I was, when one of history’s famous Chicago 7 is sitting in a restaurant window, hunched over a small table. Or you may see gnarled trunks and branches appear in a mountain dream. You might, as did my father—an aviation historian who was in complete awe of Charles Lindberg—encounter your hero in a New York City elevator. Recalling the date out of the blue, you might hear yourself whisper to him, “Happy Birthday, Mr. Lindberg!” as he exited to a floor below yours.

My father’s last glimpse of his hero was of Lindberg turning to look back into the elevator at my father. A puzzled and bemused smile was on the aviator’s face.

* * *

If I’m fortunate, these poems will fly closer to what I mean than my prose ever can. As they land, may windsock and tarmac receive them well.

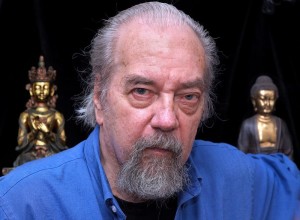

-Dick Allen

from The Chinese Menu Poems

–

House Special After the Storm has Passed

Day after day, I’ve talked to no one,

but am not lonely,

as if I’ve gone mute with a begging bowl

into the streets and everyone was television.

A small helping of chow mein,

a sip of sweet and sour soup.

What more do I need?

Mindfulness,

the Buddha said over and over,

each segment of a tangerine,

every glance or taste.

Everything I own, owns me,

the view of Spring as it merges into summer,

the silence of it,

the rock, the heron, the bamboo hut

with no one about to call out in my seeing.

Physics, the Art of Zen,

and Shrimp with Cashews in Snow Banks

What you want to do today

makes no sense,

which is why you should do it,

because it will be like stepping on blue ants,

and going to Jackson.

I’ll be

dancin’ on a pony keg.

The universe is random, I’m certain of this,

full of tree shadows and pagodas,

rice kernels and double binds.

Every once in a while

something happens on the horizon,

like a man making a pilgrimage to a far-off temple,

or a sword flashing in the sun.

You should take these things as omens,

Everything, everything

has the kind of meaning that the Japanese call no-meaning,

out there on their islands,

at three in the morning,

far from our shores. Therefore,

you should touch the treelimbs in a wooden chair,

whisper a lullaby to a laptop computer,

and stop on your way home from work

to buy something totally useless

like a small gold-plated buffalo from Day’s Drugs,

a cactus milkshake,

the Tao stones we tossed,

that rolled under the couch

and gave us completely wrong answers.

Of Chants and Music, Much of Our Life is Made

That Buddhist song of the 1960s, what were its lyrics?

Slow down, you move too fast.

Gotta make the morning last.

Yes, I remember. We were crossing the 59th Street Bridge,

loving life, feeling groovy,

and there was a war. There’s always a war.

Just kickin’ down

the cobblestones.

Body bags. Napalm. Hey, hey, LBJ,

How many kids did you kill today?

One evening at dusk

I saw Abby Hoffman sitting alone at a restaurant table,

light slanting upon him,

as if Edward Hopper had just left him there.

Praise Short-Lasting as the

Scent of an Extinguished Candle

Almost had it. There. Almost—that sense

of gratitude so difficult to keep

hanging onto—as hard to ride as a golden dragon

with its bulging eyes and protruding tongue;

as swift and momentary as the taste

of fire in a rice pudding,

the sight of crows at dawn

disappearing into a far forest. . . . In gratitude

(no Pollyannishness about it),

for the glint of sunlight on a silver car,

the cliché of a silver lining, of “it could have been worse,”

the twitch of a cat’s ears, how discomfort

goes away for a moment on a sleepless night

in the first hip and shoulder settle of rolling over,

for the sound of doorknobs turning, doors opening,

footsteps, the shape of a moon vase

completed by a curved garden bridge’s reflection

in the water beneath it. . . . In gratitude,

I write these words, trying to catch it—that man

kneeling beside the squares of a concrete sidewalk

and with a brush dipped in water

painting calligraphy which almost instantly vanishes

as he reads what he’s written,

nodding his head, amazed to have said it at all.

Eight Treasures Cooked in Chef’s Special Hunan Sauce

In “Old Trees by a Cold Waterfall”

with all those gnarled trunks and branches,

Wen Zhangming represents

endurance in the face of hardship. Yeats wrote,

“Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by.” Eliot said,

“Old men ought to be explorers.”

And here I am, following the tradition

of adding words beneath words

to a Chinese scroll painting—the Chinese-red

leather-covered journal of my 74th year

bound by a leather cord

while a Chinese-red leather ribbon inside it

keeps changing pages,

marking my passage through this lifetime,

through all this seeing and tasting,

pain, eternal pain. One accepts it

and there is always Hunan sauce, near to bubbling.

Stormy willows bend

By the shores of Thrushwood Lake:

Raindrops in the Tao.

Who shall read you, when you return,

Confucian gentleman?

Dick Allen is the author of nine books of poetry, including Zen Master Poems (Wisdom, Inc., Summer, 2016), This Shadowy Place (Winner of the New Criterion Poetry Prize, St. Augustine’s, 2014), Present Vanishing: Poems, The Day Before: New Poems, and Ode to the Cold War: Poems New and Selected, all published by Sarabande Books. He has received the Connecticut Book Award for Poetry, NEA and Ingram Merrill Poetry Writing Fellowships, a Pushcart Prize, six inclusions in The Best American Poetry volumes, and been a NBCC Finalist as well as a William Carlos Williams Poetry Prize Runner-Up for the Best American Poetry Book of the Year. Hundreds of his poems have appeared in such magazines as The New Yorker, Negative Capability, The Atlantic Monthly, Rattle, The Hudson Review, The New Republic, Poetry, The New Criterion, The Gettysburg Review, The American Scholar, Ploughshares, Boulevard, The Yale Review, The Massachusetts Review, The Georgia Review, The American Poetry Review, Agni and in numerous national poetry anthologies. He is a Buddhist who lives in a cottage near a small lake in Connecticut. From 2010-2015, he served as the Connecticut State Poet Laureate. http://zenpoemszenphotosdickallen.net>