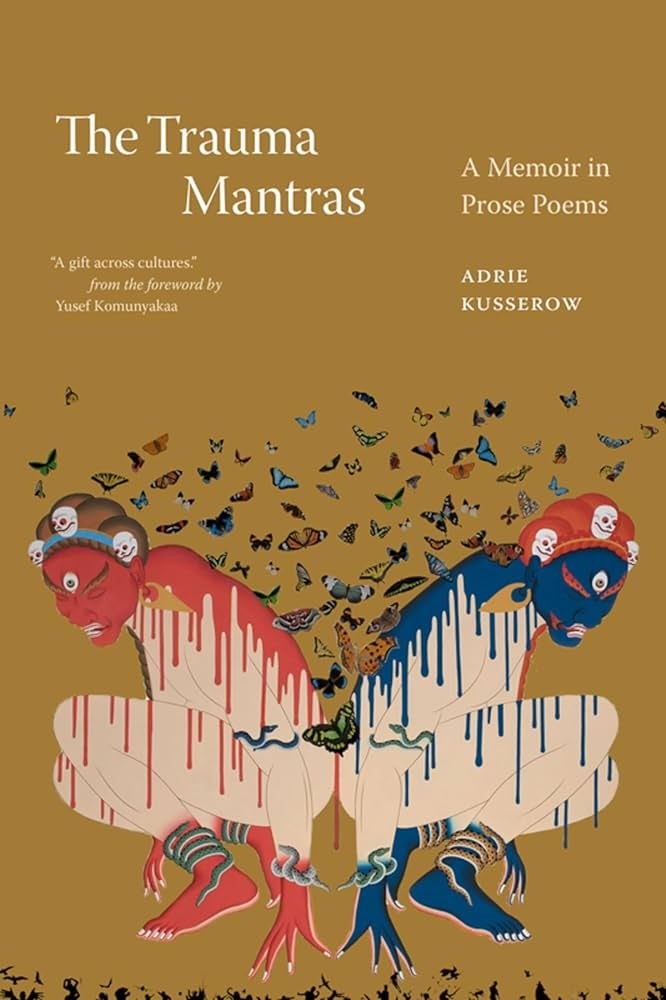

The Trauma Mantras by Adrie Kusserow

In a series of sixty-six prose poems that concatenate as memorable “reports” on her journeys from her home in Underhill, Vermont to Bhutan, Dharmsala, India, Nepal, and Sudan, Adrie Kusserow, a professor of anthropology at St. Michaels in Burlington, Vermont, witnesses to stark, developing countries’ realities with compassion, sprezzatura, and courage in her hybrid travelogue, The Trauma Mantras. With a pellucid cold eye, she documents what the poet Yusef Kumanyaka in his foreward describes as “a testament of reckoning, a solid collection of distilled observations, an upturning of physical and psychic realties, as well as heartfelt reflections…that go to the pay dirt of realism wherever the speaker travels.”

In her lyrical witness to the physical and political “traumas” that Americans are so safely insulated from by virtue of geography and privilege, Kusserow employs inspired poetic language that works also as prose to describe both the “the physical and psychic realities” of her encounters, as in this passage from her chapter titled “Bhutan, East Wants West Wants East”:

Each day I walk to the top of the Thimphu Hills, where the sun leaves its afterbirth everywhere, prayer flags drench the pines, a monk scampers away like a red fox. Couples park their cars. Condom wrappers are lodged doggedly in the mud, asserting their rightful place in the path to enlightenment. Dingy Indian buses, painted as gaudy as prostitutes, careen around the road to the capital, taking villagers to Thinmphu, where among the youth, lust for the West huddle like a fog, packs of roaming boys dressed in black jeans and T shirts, scour the streets for drugs, the ones who eye the Westerners hungrily, black eyes nibbling feverishly at the manic commercials from the storefront TVs. These boys who failed their exams, left their farms, mocking their prune-faced grandparents huddling in dark corners mumbling mantras. They want computers, not soil. Bollywood, not Buddhism.

In addition to the dystopic milieus Kusserow immerses herself in so compassionately but also “disinterestedly” with “negative capability” (that “capability as John Keats defined it as the capacity to exist “in certainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”) she includes personal, as well as pastoral “mantras” about her hometowns of Underhill and Burlington, Vermont where she lives and teaches respectively. The stark geographical contrasts her juxtapositions of continental settings evoke between her fields of study and her pastoral hometown of Underhill, Vermont evinces an engaging cultural dialectic throughout Trauma Mantras in which Kusserow acknowledges both implicitly and explicitly the disparity she experiences between the sanctuary of her Vermont home and her various far-flung homes away from home, observing and then concluding elliptically in nuggets of poetic prose “things she didn’t know she knew” about foreign, mostly oppressed others and herself. In so doing, she divines memorable verbal economy, as in this passage, a kind of credo for her own chosen literary discipline that girds her muse for transforming the act of close observation into evocative language that, as she describes it, “rises inside us when we sense something’s animacy calling us to it.” That “something” that consists consistently of human quiddity in her “entries” in which she observes firsthand the poverty, mores, suffering, dress, diseases, history, customs, humor, and ethnocentrisms of the “strangers” she encounters in India, Tibet, and Sudan. In her daring decision to wed extensive field research to expansive yet economical lyrical prose (many of which, in fact, read like prose poems, Kusserow has created a ground-breaking, hybrid form that melds poetic memoir to anthropological inquiry. In so doing, she finds a way to mine nonfiction with a poetic acumen that redefines Ezra Pound’s definition of poetry as “the news that stays news” to language that’s mutually poetic and “academic”. In a philosophical summary of her research, she concludes in one of her final mantras that “our knowledge will not prove Darwin right or wrong, it will not make us happy or sad, it will not be dystopic or utopic, apocalyptic or blissful, because our evolution cannot be dichotomized.”

This unorthodox travelogue affords an enlightened window into not only developing nations’ cultures, conditions, and peoples but the world itself which she figures into an extended metaphor as the Earth’s skull in order to evoke the planet’s essential, complex, anatomical connection to its most blessed but also problematic denizen, namely, humanity. She confesses on her last page, “I roam the earth’s skull with the same urgency as the day I first held her.” In abandoning the more purely prosaic, scientific language of anthropological research, Kusserow successfully risks fact-filled poetry to document contemporary global, social, environmental, political, anthropological, and by haunting implication, religious truths that resonates with eschatological alarm that resounds as a prophetic jeremiad in her final “chapter” where she concludes with a hard-won authoritative endnote that is both personal and transpersonal, both contemporary and ancient:

“Twenty years, an anthropologist I roam the earth‘s skull with the same urgency I first held her, feeling for the vulnerable spots, the cultural huddle, girls pass like shadows between spirit and flesh, where refugees hide in borders, where the status quo groans, the internet sketchy, Sherpas and shamans caught between YouTube and soul loss, avatars and graveyards, iPad and axe, where globalization creeps forward, drapes thinly across a villages back.

Bless the liminal, those speaking in tongues, the dented and supple.

Bless the cartilage, the soft spots built into evolution that refuse to harden.

the place on this planet with mouths hanging open, the dark fontanels that still ripple like wide-eyed ponds, the skull plates hovering like sharks.”

Throughout The Trauma Mantras, Kusserow risks essential news of the Earth and her life on and in it. It’s news that is ephemeral yet also diachronic, historic, and universal.