In her ekphrastic essay, “All These Red and Yellow Things, Short Papers on Art,” Lesle Lewis writes with a refreshingly observant eye and ear about some of her favorite works of art, reminding her readers of his or her inherent acumen for discovering exhilarating appreciation for paintings and song. A celebrated prose poet, Lesle widens her vision and aural perception for art in this essay in a heuristic way that reminds her reader of the beauty that lies within colors and sounds that often appear initially inaccessible in their strangeness or newness, but then open as revelatory images and sounds.

–Chard DeNiord

All These Red and Yellow Things: Short Papers on Art

for Ricia Gordon (1945-2021)

- Listening to the First Movement of The Palace of Nine Perfections by Eric Ewazen

The drums drop. The xylophone. It’s all percussion. The light comes into my room. For moments I can be so fulfilled. One thing influences another. The happiness is more peaceful than ecstatic. It rises and changes, but when it’s restful, it can be that way for at least short periods.

The perfections are temporary. It’s almost sad to be this happy. The music wants to be inclusive. It’s not just an orchestra. It’s also a forest. And it’s wind. Tree limbs move and cover and uncover pieces of sky. If you are in the moment, it’s not short at all. It’s enough. When it ends, it is and will be the end.

- Kate Beetle’s Pears https://www.vtart.com/Artist/Kate-Beetle/137/?

I will probably always see this painting in the context of how I met it, standing unfinished on Kate’s easel in her messy studio in her messy house. She lives the life of an odd and isolated artist supporting herself by working at the liquor store. She didn’t go to art school, but she can see classic things like still lifes and landscapes and “render” them with an exact attention.

To paint a still life, an artist must set it up, make choices that are different than for example painting a landscape that is already there. Kate has a shelf in her studio to set her still lifes on. In this case, a linen cloth with a delicate edging, a few early blossoms, a jar of ginger with a paper cover tied on with string, a round wooden box, a ball of twine, and three pears placed how they are placed. The pears are mottled as pears are. The wall behind is a white/blue/gray like a sky.

It’s a quiet painting as still lifes often (but not always) are. It suggests that life can be composed and captured. It suggests that we can be quietly observing life.

3. David Brewster’s Trench Silo davidbrewsterfineart.com

A friend once said that she could detect a person having a secretive affair because they always looked like a picture hanging crooked on a wall. Because I took it off the wall yesterday to photograph it and rehung it carelessly, I’m looking at the David Brewster’s Trench Silo now a little off kilter. And it’s not getting the light it wants and deserves. I get up, rehang it, and adjust the light. The question is why do I love certain paintings? And is that a different kind of love than any other? What does the painting tell me to do?

A barnyard, barn walls, windows, trench walls that I once mistakenly thought might contain a herd of dairy cows, and sky. What about this? There are some wide spaces, the central ground of smeared, blended color, the sky swirls of white and gray. It’s no sunny day in the world. Between these areas is a lot of action which works as an horizon to divide heaven and earth. A collection of farm buildings. At all angles. Pinkish grayish.

Two things here call to me most loudly, pull me in every time I look. The one wall and the one black window opening. That’s what this is about.

The walls begin on both bottom corners of the painting and if this is a trench silo as the painting’s title suggests, the area between the walls would hold silage, not cows. The wall that does the most work runs from the right hand (my right hand) bottom which is the painting’s left hand bottom. The wall runs or seems to run, to the exact center of the canvas. The three dimensional effect shows how things are but also how they look. The plane, the flatness of the canvas, is destroyed. How is this wall that lies flat on the canvas but also dives deep into space different than, for instance, the stone wall out my window, the one mostly covered in snow and catching sun on a two degree morning? One wall runs more literally away from me (also runs without moving), but both run. The Brewster wall draws me with great force into the central busyness, but it’s the wall and not the busy center that I look at and care about.

So much happens in the middle, but I seem to never spend much time investigating the busyness in the middle of this painting . Maybe I never stand close enough to study it. Instead, as I follow the wall, I get immediately swallowed into the black hole of one barn window, a dark vortex like middle-of-the-night thoughts that are about real and inevitable bad, sad things, and the infinite post-life time. I have a tiny bit of control over, if not the truth of darkness, suffering, and death, the thinking about it, the attention I give to it. I can pull myself out of the window and come back to the white puffs and red barn slats, and rooflines. There’s even the other wall I never spend time with going down (or up) the other side. Plenty to pay attention to in the activity, plenty of investigating, and studying and work to do. I could investigate the trench silo method, how the silage works to feed the herd, the cleverness of farming. There’s almost too much happening: another piece of cement wall, some sheds, one open with supporting posts, some low roofs, high roofs, probably sheet metal. This busy middle place is a big part, maybe the main part, of the real life but the flat planes that lead us to it and the swirling heavens above are where we spend our time, that is unless we get pulled into that dark window. The painting is very directive. I’m at one with it.

What happens when an artist sees something and refers to it on a canvas? It’s not an abstraction, but a namable subject. What interests me though is less the subject and more the different ways to see the somethings that already exist in the world. It changes me.

- Ricia Gordon’s Fisherman’s Fu https://riciagordon.com

I think I get this painting and I love this painting because of the amount of activity in it. It’s the same amount of activity that makes me write. What else can I do?

There’s a lot of blank canvas showing, but it’s not blank white. There’s a hue to it. There’s a bit of penciling here and there. There are a few marks and drips separate from the main action. So while the main action is the main action, it’s in a context that’s not simple. There’s a bigger world than this painting and it’s the world the painting is in. Sometimes I focus on the four red drops, sometimes the bleeding drips, sometimes the white hieroglyphic scribble, or the isolated white dot, or the almost hidden whites and pinks.

I’m moving now into the palate choices: bold red and yellow and white and green, in-your-face colors, and yes, maybe floral-like, not in a conventional pretty way, but more insistent. Most of the red and yellow colored shapes/marks are circular like the brush went around itself and said, “here” and “here” and “here.” If they dripped in the application or blended with something else, so be it. The consequences matter, but will not inhibit the action.

The green plays a more subtle role although it’s right in the middle. It’s like a second layer of background. It’s where the other colors are coming from. On the canvas is a square of work and in this square of work is a field where colors exist simultaneously loudly and silently. There is this green and on that green are all these red and yellow things.

And around this action, a few white this-this-and-this marks. All the marks and all the colors are exactly and boldly themselves. We don’t need to try to understand them, and they need not understand themselves. They are busy, a little upsetting, what they are and have to be.

The pieces I choose to write about are pieces that teach me, but only after I work at them which is to spend time with them, a lot of time. And to write about/to/with them. Ricia’s painting tells me to not just let myself be myself, to not just think and feel what I think and feel, but also to not avoid my own disruptions. I need not make cautious distinctions. I can say “this.” I can say “here.”

The penciled title of the painting Ricia took from my poem, but I don’t think that connection is why I love looking at this work. I love looking at it from my bed every morning because it helps me get up and do another day.

- The Throat Singing of Mongolia

I can only listen and then peek from my limited, innocent, naive stance. The sound is deep and high like mountains or oceans or sky. While I listen to it, Dan snowblows outside the bedroom window. A snow-covered pine sways. The everyday falls away or at least I can handle it better. The singing works like a portal to the outer circle which might be nothingness, but is also everything. It might be dark or terribly bright. I’m on the edge of it. There’s something vital about this portal existing. Desire, maybe desire. The truth of it includes the irreconcilable.

- Finding Will Henry Stevens https://www.bluespiral1.com/artist/711

I never paid much attention to this pastel passed to Dan from his grandmother to his father to him, a not-quite typical, conventional rural landscape. When we miraculously discovered a collection of Stevens’ works in a gallery in Asheville, something changed for me. Stevens’ work stood out in that gallery. We figured out who he was.

Here is a bridge, a path or road, a stream, a barn, more distant roofs, telephone poles, trees, a giant hill, sky, yellows and greens and grays and pinks and blues. There is an awful lot going on in the piece because there’s an awful lot going on in the scene in the world. Let me say the things that I love the more and more I look. The bridge for its smallness and simple fence and the pinkish road that goes over it. The darkness of the barn with its even darker barn door. The slant of the poles. Across the stream, the yellows and greens, early summer maybe. One evergreen tree that stands in a subtle yellow halo. But the hill is the monster subject here and not as detailed, but looser, bordering on the abstract, powerfully looming. I hesitate to say this because I know I’m a broken record, but the hill is like death, what stands behind all the small beautiful things. And there’s a smaller blue hill beyond and then sky, always sky, shades of blue, white, pink.

It’s almost like we have a choice. We can live (if we’re lucky) in this pretty valley. We can not look up at the hill. Or we can always be looking at the hill, what’s beyond and not clear. Of course I don’t believe this was in Stevens’ mind while he painted this (pastel pieces are sometimes called drawings and sometimes called paintings, a distinction worth investigating). So there’s metaphor to think about: metaphor intended, metaphor unintended. In whose head does the metaphor live? I think about the “looming” hill and other looming things. How we live with them. It brings me back to the idea that all things matter, but not equally. The fenceposts and the bridge and the colors in the valley matter. The looming hill matters. Which matters more? I have more to think on mattering (importance, significance, interest). Do we, can we, choose what matters to us?

- Find Joy Early: music by Ten by Twelve https://tenbytwelve.bandcamp.com/releases

The start is far away. It walks towards me. It’s dark. There are a lot of pieces to it. They walk along together. I can’t pick out the instruments. Percussion mostly and a bell-like thing that says something more particular. A voice rides along. We’re in the same place for awhile, but then a new thing rises and falls and slides into echoes or valleys. It tries to stop itself but it can’t. It fights itself a little, some resistance. But then it catches on and we can be with it. It wants us now. It’s a little scary to give ourselves to it. It slows us and totally takes us. This is joy? It’s a very different life. Something doesn’t want us to love this one. Almost a voice, but not a voice. It could be frogs or a xylophone or ghosts. A lot of people don’t understand. There are things I haven’t told people and that’s okay. I’m okay. I could just be okay. So maybe this is joy. It’s pretty insistent. It very much wants to be. I could let myself be in it. I let myself be in it. It’s not a simple comfort. It’s up there. It wants to be loved. Is this making you nervous? It goes on. It finds a new direction. It may have no reason to ever end. Does it get tired? Does it ever stop liking itself? It’s having a mood. Someone, the musicians, need it. To be just this. But it’s allowed to drift. It could be the bells of Montalcino for me. It could be Idolina or someone else who has died. Now something else new comes as such things do. New people. My stomach is not sure about this. It’s a lot of people, each with an entire life, long or short. Or it could be a lot of animals. Or lights. There’s something else behind it now. Electronics. Stars. Insects. Bodies becoming bodiless. Houses floating off. Faces changing. Kitchens becoming bears. Cymbals. Everyone forever. Quietly going. A rising, We feel it’s the last. Crash. Last slide down. Last screech. To end stop.

This is not all pleasure to listen to. I’m overwhelmed by the possibilities, not eased by what art can do.

Ricia was also a musician and made this music with her friend Russell Horton. I’m listening to this frequently now.

- Listening to Satie’s Gnossienne no. 1

I listen to Satie in bed on a snowy morning in March. I have no choice about the snow fall being what it is. It’s not sad. The snow is not sad. The music is not sad. I feel if I recognize the moment, I can see it as it is. It’s just a piano, just a day. But sometimes it’s at odds with itself. Sometimes the music demands us, directs us, to take a narrower path. It brings form to the messiness, but also complications to the clarity. I can watch the snow fall, listen to Satie, and my heart could break. I could be cold and lost in the woods. Where do I look? Where do I live? What will happen? I could listen to this forever, and I could live longer.

When an art piece like this piece of music gives us something we need but don’t know that we need, we might welcome it or we might ignore it or we might even argue with it. Knowing something we may not want to know makes life harder and simultaneously more worth while.

9. Off Cape Cod by Thomas Castle (circa 1940 – no artist info. available)

It’s almost all atmospheric. The orange-gray sky is reflected similarly in the sea. The horizon is a darkness, almost black, and not completely flat like the horizon really is. The sun is minutes away from disappearing (unless it’s coming up of course). The boat has a single mast, but no sail. Maybe two figures. It’s probably a fishing boat. People at work. What we call “work.” Art-making as work. Art products as work.

There’s the sun to think about, what we think of as its coming and going. Clouds come between us as do trees and houses and skyscrapers. Our loved ones sometimes block our sun.

I’ve been listening to Paul Fry’s Yale lectures on art history. If realism is “too easy and confining with its limited possibilities,” and “hence the rise of the aesthetic of romance,” this watercolor serves as an example. Yes, the sun and the sea and a small fishing vessel are real things in the world, but they are softened here, romanticized. We don’t get the fishermen’s exhaustion or concerns here, but a beautiful scene of humans in the wonder of the world. But if on the “political horizon,” a piece of art can resolve contradictions, this can be seen here too. The contradiction is that the natural world is “wonderful,” but also unconcerned with us. The contradiction is that we work and suffer in the world and might also be awed by the world’s beauty, Yes, there’s a “historical horizon” as well, the romantic “resistance to industrialization.” Art as “resolution” of contradictions, or if not “resolution,” the recognition of the contradictions as a way to live.

- On Reading Sherod Santos’ “Seven Seconds in the Life of the Honeyed Muse or, What is Art?” (in American Poetry Review January 2019)

Santos begins by reminding us that art is an idea. Yes. The idea is that we look at art differently than we look at the rest of our everyday worlds. It’s been said that an object “liberated from its function” can be called art. And the art is inside the thing.

The idea of beauty has become suspect, suggesting something is “merely” pleasant to absorb. As if that isn’t wondrous.

And the “art” of things less commonly thought of as art? The art of conversation. The art of loneliness. The art of motorcycle maintenance. The art of dog-training. The art of living healthfully. The art of war. The art of identity politics. The art of hosting. Does it suggest a quality beyond efficiency? Something distinct from skill, craft, practice? The art of thinking.

Santos nails it. “Words can never fully shake off their sense.” A good thing and a thing to work with. The Santos essay works by parataxis. This is something to consider when asking “what is art?” and so is this.

And the notion that an art, a poem, is for someone besides its creator? How vital is that?

I used to tell students that if they didn’t work on their written work, that was okay. It was theraputic to create it. But if they worked on it so it could work for readers they were approaching making art. I no longer think this. The distinction is fuzzy or not even existent. We write to fulfill a need, to put something into the world that is lacking for us. So that’s functional. And then it might also fulfill a need (the same one or a different one) for a reader. Also functional.

Santos reminds us that our cultural, historical, time-related views change: on feminism, on nature. But it works both ways, doesn’t it? Art reflects the views of the times, but it’s also capable of changing our views which is why it is so necessary. But that’s not quite it. The artist is not saying, “look at it this way,” but just “look at this” because the artist can’t help herself looking.

Santos cites Gould and Proust on that something that is in art that is most vital, that is not known without the work. It might become known in the composing or in the writing or in the listening or in the reading. It’s what presses the artist. What makes one “ardent.”

Santos brings us to ask, “What it IS that’s in art?” Enough to think on for the rest of my life. Not something to write “about.” I am lost in it. The “it” in art, like the “it” in everything is to keep trying to get to, but we can only get closer, never all the way there except in rare terrifying, ecstatic flashes. It’s unspeakable. It’s not all dark or all light or all good. It’s not nothing, but yes, nothing.

First off I balk at Santos naming one of the “unspoken task(s)” of art to be “to distinguish between the real and unreal.” But I take to heart Santos paralleling art’s task to the tasks of religion and philosophy.

Realism is pitted against idealism, and that distinction too I find bothersome. Could I say that idealism is a part of realism just like the unreal is part of the real? That’s different, than saying the afterlife is part of life, isn’t it? Death is a pretty clear divider.

And what do I think of Plato’s divine ideas? I’ve never really bought into it, so Santos’s discussion of an artist’s rendering of a bed which is a “copy” of the Divine Idea of a bed, falls flat for me.

And then we come to/ get to things that are “not nothing,” but do not “appear,” things we’ve named “air, death, God, love.” Yes, now we are getting somewhere. Of course the naming is problematic. I’d like to title a poem “Air, Death, God, and Love.”

Does it ease me a bit to read “Things are never only one thing”? My head is blowing up.

I know this isn’t about me, but what question can I take from this into my day? There’s the question of art’s “task.” There’s the question of naming. The notion of “unconcealing.” The only way I can survive the bigness, the overwhelmingness of the unknowability is to use language on it, the “it” being the things that are not things, the end of thingness.

Santos’ questions are similar to mine, if so much better articulated. The notion of individualism that haunts artists: is it outdated? Is expression of the innermost self a necessary honesty, “I’m the one saying this”? Is the self more practically the tool for the work, the tool rather than the subject? It is also important to consider how the times, political, cultural, and environmental affect the artist, both above and below her radar.

Never mind the “history” of artistic creation, the days of magic, the days before theory. Was it still art?

And aesthetics! Something else I’ve been wondering about: how I like so many different kinds of paintings for instance. Have I no taste? No aesthetic leaning? Is the rainy morning becoming sunny? And the sublime? Can we ever agree on beauty? Would it be bad to do so? What about acceptance of even more eclectic aesthetics? What do the times call for? What do we need now? More love for and caring for the natural world.

Museums might make choices for us that we can object to, but they also allow us to see things we might not otherwise. I am grateful for them.

And Dewey’s hypothetical example? An object thought to be human-made turns out to be a “natural product,” so it is moved from the art museum to the museum of natural history. What of it? The wonder of it is that interesting and/or pleasing things can be found and can be made. It’s a wonderful dream world! When the awesomeness of nature washes over us, we have a response like the one we can have to art, so sometimes we think there must be a creator of it. And art, of course, can copy nature, respond to it, argue with it, collect it, describe it. Yes, a dream…..

For example, the exploding cow. How open-minded can we be? Why push ourselves?

Little Lulu and I walked around the Guggenheim. I didn’t know that my answer to her question, “What makes something art?” was exactly Duchamp’s answer. It’s art if the artist says it is. That question is not one I wonder about. Of course there’s great art and not great art. Of course because people and their lives are all different, they need and want different things from art. Why do we need it so badly? Why do I think that studying art is so vital?

Santos asks about the “newness” notion. He talks about a necessary “displacement” of the old. But there is also a building on and from it. And some art that never gets old. Virginia Woolf will never get old. Yes, Santos recognizes “tools and methodologies” that allow and move art. We are teachable and we learn.

If a cocktail in an empty gallery is called art, it is art. It is something made to be art. I’m done with the defining question. I have so many others. What can get me through this dark day?

And the desire that drives art, how is it and how is it not, a kind of lust? Can destruction of art also be art? And is hate for art a terrible illness? Santos cites some notorious examples of “vandal art.” They speak to the great power (threat) of the pieces destroyed.

Acid, pickaxe, bombs, saws, knives, fire: weapons for destruction that can be used on art. And what about mocking? Ignoring? Debasing? Contradicting? Censoring? Is that the art existed at all (and not its longevity) its glory?

And art as manipulation? The horror story that pulls on your cruelest thinking. The music played for dramatic effect at an execution. The love story meant to break your heart. Art is used this way too. With malevolent intention. So art is not necessarily good? Should we judge it by its usefulness: the other side of the picture, not creation but reception/effect, the artist’s control of that, the manipulation of it, the concern for it, the lack of concern? And if we are aware of so much need in the world, the art that’s most necessary and most appreciated is the art that attempts to address the neediness by acknowledging it or critiquing it or advising it. This is sensible. Some of our needs are metaphysical and unknowable, or unnameable, unsolvable, unfulfillable.

Two questions here: one on intention and one on reception. And also the third way of meaning too, what the art does that cannot be controlled by its maker and that stands independently from its receiver, that power that can threaten us and/or make life livable by acknowledging what is unknowable. We can explore what is without substance by exploring substance so that even when metaphor is unintended, it talks.

Can there be an art that fulfills all needs so there is no longer any need or any art? Is there art striving to undo itself, to satisfy a need and be done?

Silence might be the place to start from as well as the place to end, the grand and most true and enduring nothingness we shout into. I think of the three circles, the private person, the greater world, the even greater abyss. Santos says, “Art appears to have a life of its own.” Perhaps it’s not just that we need art (whatever it is) but that art needs us.

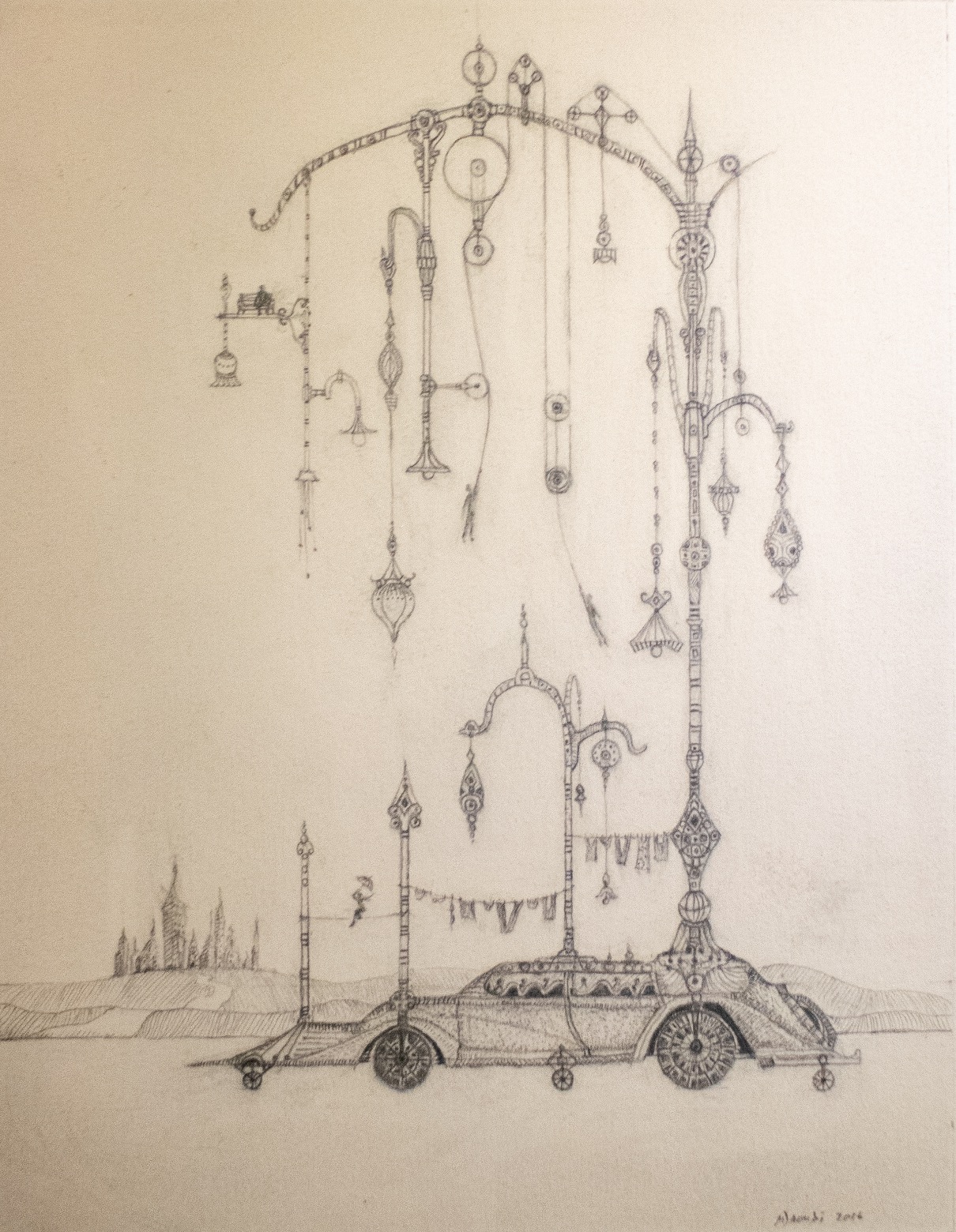

- Mohammed Daoudi’s Car mohammeddaoudi.com

This drawing as invention. The car drives on a blank road. Beyond it, hills and a small, tall city, context.

It’s a long, sleek beautiful car with five wheels on this side and if it were an actual car in the world it would have five wheels on the other. Lines and marks make shading, make the wheels into small mandalas. The car might live and drive, but it also grows spires that shoot into the sky and carry tiny whole worlds: clotheslines hung with clothes, a tightrope walker with umbrella, gears, lampshades, many lamps, ornaments with no recognizable functions. Things hang, dangle elegantly. One little person sits on a little bench. Two figures swing from ropes they hang onto.

Why is this not all fun for me? Do the details remind me that there are too many things in the world to take in? That invention is endless? Our work never done? If the details of the world are nearly infinite in number and the potential details of our inventions equally so, how do we ever feel easy, ever rest? Never mind there are all our individual pasts, all our histories, and all our futures.

Yet we can make crazy, pretty things like this car and drive them. We can call a drawing finished and frame it and hang it.

- Partita for Eight Voices by Caroline Shaw performed by Roomful of Teeth

A twenty-four minute piece. First listen while I’m sitting by the woodstove. The voices start with talking, repeating as if the words are flames in high octaves. As if I could lullaby myself, the music takes me away to a higher, not all-happy or all-sad place. Everything deeply is. It’s lonelier than the voices suggest. The voices merely hint at it. It reminds me of the possibilities of going further, going all the way, like tripping. I don’t need to hold on so tight, do I? One word is what it is in part because of all it is not. This music is what it is in part due to what it is not, its limits. It takes us away but not all the way away.

I begin my second listening with a list of obligations in my head, obligations to people who want my caring, a number of people are now waiting to hear from me. I’m finding worries to worry me now. I’m waiting for the voices to take me again.

Is my writing to merely hold me together? If so, it’s necessary, but because it may not add anything useful to anyone else, I also must be giving and kind to people in my life. Art isn’t everything. I have to do so many things. But why can’t I just scratch my head and sit in the sun and love the world from a sitting position?

The voices rise and hum. My problems are small. I’m lifted. The differences are small between talking and breathing and singing. The eight voices make all the sounds and moods of humans. They wind around each other.

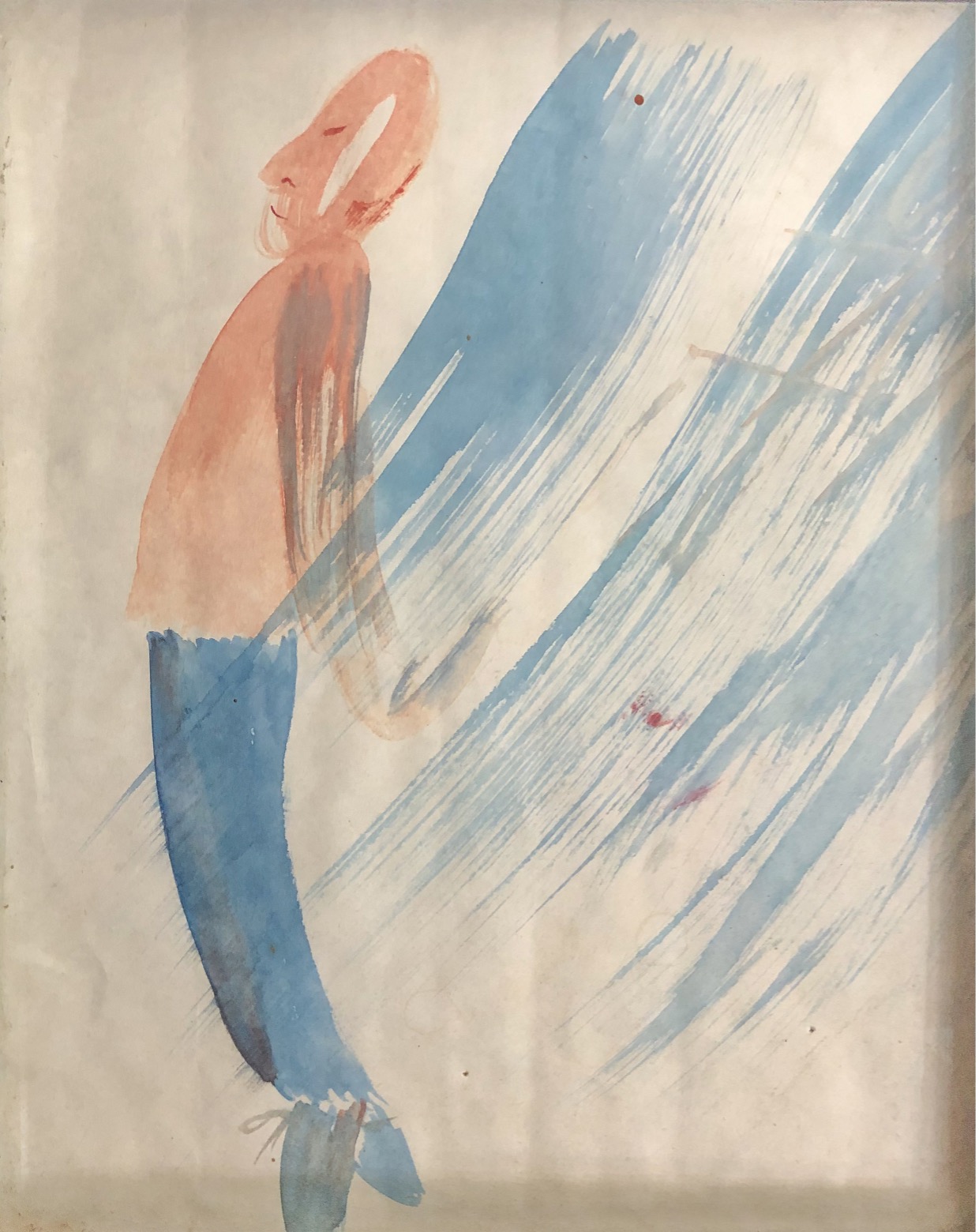

- The Push of Miki Nilan’s Guy miki nilan

I think this was a quick watercolor drawing. Miki gave it to me on one of my visits. How can Miki not be doing art? She is an artist.

I need to frame this piece I love it so much and it has traveled with me from office to office, study to study. The figure in blue and orangish brown has an attitude. His body is arched in such a way that it seems to be in negation to something, in refusal to what’s at his back, the blue rush of brush strokes. He also seems ungrounded like he is floating or being pushed in the air. His face is stern. The unpainted middle of his head is white and connects him to the white of the page and world off the page. His arms, half blue, the color of his pants and shoes and half the orange of his shirt and head, incline backwards which suggests to me he is pushing back on whatever is pushing him. He is sternly himself. Or maybe he is allowing himself to be pushed this way, accepting. Addressing this difference in interpretations is worth my time. Never mind a note on the graceful curve of the figure’s body, and the rush of blue strokes at his back.

What I see here can change day-to-day and yes, is dependent at least in part on my state of mind. One day I may see this figure as a man with intention, a man with a plan, a man in resistance to outside forces. He is a figure with agency. And another day I may see the figure as pushed against his wishes. And yet on a third day, I might see him as pushed but

Do we believe things based on knowledge or without knowledge? Do we look for information that will support our beliefs or attempt to seek out information without the bias of belief? Do I assume Miki’s intentions based on what I believe about this piece? Or do Miki’s intentions drive my beliefs? Did Miki have an intention? I believe (yes believe) that the “best” art is born without too much intention. The artist has a need, has questions, has a discomfort, and from that comes the art which tries to fulfill the need or answer the question or comfort the discomfort. How it does this surprises the artist. And then there is the art-receiver, audience, viewer, reader who has needs and a life of her own that she cannot see without. It’s so clearly a complicated three-way street: artist, art, receiver.accepting of the push. So this is a good piece for investigating the usefulness or uselessness of interpretation.

- Logging Grapple: another David Brewster davidbrewsterfineart.com

The painting hangs on the other side of the windows. A darker work. It’s certainly not getting enough light. It faces me squarely. The two windows next to it are rectangles. Its sister, Trench Silo, on the other side, a horizontal rectangle. I will work on getting it better light, but meanwhile I am directed by the logs sucking me into the machine with its blue tire and its reaching arm in the center. Then there’s also that shine of solid white light on the ground like the white stripe of light in Sargent’s Venice Interior. Then there’s a solid patch of blue sky. And I say then because I don’t see it all at once. I move into it.

All around the sides are dark, wild colors which could be trees. I’m being sucked past the trees into something, a machine, a darkness, but not one without redemption, the blue sky. I could focus on the log piles, the machine, the wild dark woods, but what pulls on me are the logs that rush and point me inwards, the light on the ground and the sky beyond. It’s like someone is saying that if I commit, if I follow, yes, it will be work, and yes, it will be dark and noisy and frightening, but yes there will be some light at the end, sky or even death.

I am not saying that David Brewster was thinking this, had this intention. Nor am I saying that I know more about the artist than he knows about himself. I am saying that the choices the artist made result in something previously nonexistent and unpredictable. And of course I’m saying something about myself, why the painting does what it does for me.

I can guess at David’s intentions, to show us the logging grapple in the dark woods and the shine of light that comes through. I can immerse myself in the paint on the canvas. I can question my own obsessions (light, darkness, death, etc.). What we mean by meaning might be both purport and import, purpose and significance. Also sense, implication, and tenor. The painting does its good work without caring about the artist’s intentions or anyone’s interpretation or reception of it.