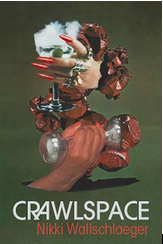

Crawlspace

Nikki Wallschlaeger

Bloof Books

$16, 82 pp.

May 2017

“instead of the stanzas the rooms”

—Bernadette Mayer

Poetic forms are constraints. A constraint gives form and body, and also creates space. A body is a constraint. A sonnet is a constraint. A body is a sonnet and a room is a sonnet. And like bodies and rooms, sonnets take different shapes, variations on a theme: limbs, torso, head; walls, window, door; fourteen lines, argument, volta. In Nikki Wallschlaeger’s Crawlspace,the sonnet is a tight space to crawl through. Mostly, the spaces are a standard fourteen lines long, but sometimes the space will open to another fourteen-line space and another. The final poem, “Sonnet (55)” is six sections long. These sonnets are unexpected, sometimes disquieting, and angry. A Lucille Clifton quote opens the collection: “all of us are tired / and some of us are mad.”

Every poem in Crawlspace is numbered and titled “Sonnet”: “Sonnet (1)” through “Sonnet (55)”—though there are only forty poems in the book. The absence of some sonnets broadens the collection, making it feel larger than it is, like adding a mirror to a small room. The missing sonnets signal, perhaps, to a process of experimentation: squeeze an idea through the opening of the form and see how the shape changes when it comes out the other end. Discard whatever doesn’t work or isn’t interesting. But they also might be lost underneath the others, as objects in a crawlspace might be present, but unseen and out of reach or even forgotten. Wallschlaeger’s limited use of punctuation and long lines further compound the sense that these poems are searching through or stuffed into an enclosed space, especially when the lines are longer than the poem is tall. It’s as if adding punctuation wouldn’t allow the door to close, the contents straining cartoonishly at the doorframe.

Writing on Bernadette Mayer’s Sonnets, Lee Anne Brown wrote, “Spliced throughout with compositional strategies like collage, reversal, found language […], uncensored language, and aural/inventive spellings, these poems show what happens if [Gertrude] Stein’s ‘language is a real thing, not an imitation’ is true.” Nikki Wallschlaeger’s sonnets operate in similar ways, an extension of Mayer’s project, including the similar concerns of parenting and domesticity. The ending of “Sonnet (13)” is typical:

Mother you need is going to yell at you

I know what you want

but you’re gonna have to write it down

Home life and motherhood intersect with the experience of being a black woman in the U.S. and the constraints a white supremacist culture places on the lives of black women. Throughout Crawlspace, Wallschlaeger knows exactly how and what she accepts and rejects when using the sonnet form. “Writing under the constraints of your oppressors, whoever they are,” Wallschlaeger writes in “Sonnet (15).” In “Sonnet (29)” these identities—mother and black woman—are both explicit:

I wear their food all over my clothes

shopping for more lifestyle items

You can only play with squirt guns

in the backyard never the front yard

The first two lines here speak of a comfortable middle class, the speaker financially stable enough to shop for “lifestyle items.” The next two lines disturb the narrative since only non-white parents (and primarily black parents) have to teach their children to be cautious when leaving the house, even just in the yard, especially when playing with toy weapons. Later, the poems mourn those who have been lost to violence against black people: “Face me in your sonnets so I can permanently grieve,” a flower garden says in “Sonnet (36).”

Like many of the poems in Crawlspace, “Sonnet (48)” is a persona poem. In it, “a hired slave maid” midwife addresses the white baby in her care: “Don’t worry I got a nice / big brown titty for you / but first I gotta eat,” she opens, before thinking about taking baby away from its mother:

if you were mine I’d

take you out of here

away from that mama

of yours that had no

business having babies

if she was going to hand

off to someone else

to a hired slave maid

like me to take care of

“Sonnet (48)” stands out as being the only sonnet in which a section is fewer than fourteen lines. Referring to the things she’s said to the baby, the poem ends,

and I’m going to say em

before you become one

of them and I hope you

can hear some of what

I’m saying or at least

Feel it yes

The final eight lines aren’t missing, exactly, simply implied—she has finished eating and the baby has latched on, all of the fraught power dynamics lingering and echoing in place of language. You can hear Lucille Clifton’s lines rumbling here, too.

In Crawlspace,Wallschlaeger hasn’t changed the shape the sonnet, but she has used it differently. As versatile as the sonnet is, it’s generally used to contain something, not alter it, and certainly not in quite so physical a way. But the constraints of the body changes the way we interact with the world, so why shouldn’t a poetic form do the same for its contents? By letting the mechanics of the form alter the language she puts inside it, Wallschlaeger has found a way to unsettle expectations and surprise. It’s an experimental poetics, but one that is always aware of power dynamics and history, and reminding us, as experimental poetry sometimes forgets, that language is a real thing and forms are bodies.

Nikki Wallschlaeger’s work recently has been featured in jubilat, Georgia Review, Boston Review, Denver Quarterly, Witness, PoetryNow podcast through the Poetry Foundation and others. She is the author of the full-length collections Houses (Horseless Press 2015) and Crawlspace (Bloof 2017) as well as the graphic chapbook I Hate Telling You How I Really Feel from Bloof Books (2016). Her bio can be found at the Poetry Foundation < click here>. She lives in Wisconsin.