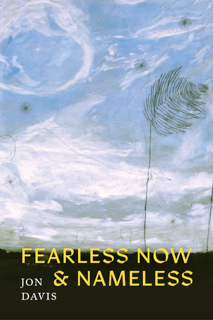

Fearless Now & Nameless; a tour de force from poet and musician and shapeshifter Jon Davis

NM: Three epigraphs, from Wallace Stevens, Basho, and Louise Glück open your new book, Fearless Now & Nameless.

What themes do these epigraphs announce?

JD: A little history is in order. After my last book, Above the Bejeweled City, I wrote a book-length manuscript called Anathematica, a collection of poems marked by rage and satire and despair. I enjoyed writing that book– probably too much. One of the two epigraphs for that book was from End Game by Samuel Beckett: “You must learn to suffer better than that if you want them to weary of punishing you.” You can imagine where that project was going.

Then, suddenly, things began to shift, not so much in the world–you’ve seen the world, right? –but in me. Fearless Now & Nameless arrived suddenly. It may have been “Wallace Stevens on the Moon” that effected the shift. In that poem, begun as a kind of joke–someone once said “We should have sent Marianne Moore to the moon”–I found I was released from my imperious rage into the delights, misdirections, and redirections of language. Since I was wearing Wallace Stevens’ oversized suit and had no destination in mind, I could follow the quicksilver cairns of language wherever they took me. A handful of poems from Anathematica would survive, but the new poems arrived quick as New York subways in rush hour, each one surprising me with its bustling energy and range.

NM: Hmm…interesting you credit Stevens with this shift; in my first reading of Fearless Now & Nameless I immediately associated the first four lines of the opening poem “In Gioiella”

I was so new

I didn’t know

what to attend—

the bells of sheep

or the huddle of them

to Steven’s V of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendos.

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

JD: Although I wasn’t thinking of Stevens in that poem, he’s always in my ear. So, it doesn’t shock me that there’s a similarity. So, the first epigraph was–surprise! –the Wallace Stevens quote from “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven”:

“It is the philosopher’s search

For an interior made exterior

And the poet’s search for the same exterior made

Interior.”

— Wallace Stevens, “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven”

The second epigraph is Robert Hass’s version of Matsuo Bashō’s haiku:

“Even in Kyoto—

hearing the cuckoo’s cry—

I long for Kyoto.”

In Basho’s poem, the speaker’s desire challenges his ability to be present to the moment. This has been a consistent theme in my life and poetry. I realized recently that Basho’s haiku amplifies an epigraph from Ralph Waldo Emerson in my first book, published in 1987:

”Must every experience–those that promised to be dearest and most penetrative–only kiss my cheek like the wind and pass away?”

“The songs have changed; the unspeakable / has entered them,” writes Louise Glück.” Poets are fond of announcing they are trying to “say the unsayable,” but Louise–in a very Louise move–says “the unspeakable”–those things that, whether because they are too damaging or because it is socially unacceptable to utter them–had not previously “enter(ed) the songs.” This epigraph arrived after the Stevens and before Bashō. It addresses another thread in the book—family secrets, my own foolishness, and the loss of friends and family members. During the writing of this book, I lost two uncles who were very close to me, my mother, my stepfather, and several friends. My father and three brothers had died earlier. I was the last one standing; their loss both burdened me and freed me. Those burdens and freedoms haunt the book. And, in some cases, release the “unspeakable.”

NM: I was immediately struck by the language—such music and playfulness in imagery and syntax, the rhythms of bustling energy free-ranging expansive, unfettered. Exactly how did the poems arrive, as you say, quick as New York subways in rush hour? Every day, in dreams, or walking? Did you write most of the book in a short time? Outside of Stevens’ poem what was happening in your personal life that might have transformed, sprung you into this new terrain?

JD: You’ve asked several questions there. I better answer them one at a time.

So, how did the poems arrive? Poetry is so central to the way I move through the world that I write anywhere and everywhere—whenever a line or lines emerge. “I’m guarding a poem,” I’ll often tell my partner, so she’ll know I’m only 20% present. Many poems start with a single line that I’ve texted myself during the day. Poems often arise out of conversations, text threads, Facebook messages, or out of my always drifting brain. There’s a suddenness to many of the poems–much of the time, I don’t have a memory of where I wrote a poem and what prompted it–but others I build slowly, stone by stone.

“At Cill Rialaig,” for example, came out of a phone call with my friend and bandmate in Clap the Houses Dark, Greg Glazner. He was telling me about a book he’d just read that, frankly, was just beyond my reach. So, I wrote the first four lines as if I knew what Greg had been talking about. I now hear echoes of Robert Hass’s poems in “Praise,” those poems that begin in abstraction:

If experience is what gives the world its shape,

the fundament and glyph, the harkening ear

of everything, then the frogs chorusing in the bog

are the heterodox archangels of County Kerry.

Then I followed language and image and resisted the intelligence pretty darn successfully. It’s one of my favorite poems in the book, partly because I don’t thoroughly understand it.

I’m realizing as I think about this how often there is a person– a friend, acquaintance, or family member–as the presiding spirit of a poem. Dana Levin inspired “Asterisk as Ornament,” though I can’t remember exactly why. Maybe an Instagram post? “Spontaneous Knotting” arose out of an article in the New York Times about dubious government-funded experiments. The writer of the article said that “Spontaneous Knotting of an Agitated String” sounded like a Wallace Stevens poem waiting to happen, so I couldn’t resist. My mother is at the heart of a number of poems. I’d forgotten that she cleaned houses when I was six or seven years old; and tried to capture the tone of those pleasant days in “In Rooms, In Language.” The pleasantness was, of course, a refuge from what was happening in the world. Eventually that world crashed into the poem. “A Few Questions for M” is based on a word game I played with my mother when I was young. A description of that game is on my website jondavispoet.com, should anyone be interested. The game drew connections between words based only on sound. That game contributed to my feeling that words are related to each other by sound as much as meaning—a feeling that both leads me astray and leads me to discover surprising connections. For me, finch and filch and flinch are more closely related than finch and sparrow. Such connections are thrilling, in that I’m forced to rethink the relationships among finch and filch and flinch. Though not attributed to Stevens, “The Kettlefish” was an early poem in which I took great pleasure in working the sound first. If there was a flat moment that just carried information, I’d go back in and amp it up, which sometimes changed the poem entirely. “Update from the Chamber of Commerce” occurred during a round of Facebook messages with the poet John Gallaher, who was hoping to visit Santa Fe, but was worried about the drought we were in the midst of and the fires that then surrounded the city. I wrote part of it in a message to John, then opened a Word document and wrote the rest, after which I sent it to John. “An Open Letter to My Poems” was written during a break while Greg Glazner and I were composing “Over the Transom,” a song that would appear on Clap the Houses Dark’s debut album. “Flamenco Recital” I wrote in the back seat of the car on the way home from my granddaughter’s flamenco recital filled with joy shadowed by time and sadness and beauty. “Of Light and Time” was inspired by a Facebook photo of my childhood home, posted by a former neighbor.. “Carnal in the Land of Blood and Beauty,” I wrote for my friend and frequent cover artist Grant Hayunga’s gallery opening. You can see a six-foot-tall version of the poem in the Grant Hayunga Studio & Gallery in Santa Fe. Although I often dream poems, “The Gathering” is the only poem that I dreamed in this book.

Did I write the book in a short time? Fearless Now & Nameless was written quickly–probably under three years–with most of it written in the last year before it went to press.

What else contributed to the tonal shift from the abandoned manuscript to Fearless? Two things probably contributed to the tonal shift: people close to me were dying, and a second granddaughter arrived. I had no idea I would love my two granddaughters as much as I do. Nor how the death of my mother and my uncle’s dementia would startle and disturb me.

NM: I keep returning to your poem “Against Deliverance” about your mother’s death with the same wonder (like, how the hell did he do that!) then I return to Stevens’ poems.

Against Deliverance

My mother believed in nothing and to nothing was delivered.

While firebirds circled the chimney.

While I drove from exit to exit, eastern Pennsylvania and nowhere to sleep.

To sell a handful of books to the citizens of Nashville, I’d driven.

To see Rancid and my nephew and return.

Driving was battering lights, darkness and fear.

Driving was twenty feet of road and music: “Lord, I’m going uptown.”

I’d been to Nashville and was returning.

When the call came, I could not answer.

The last time I’d visited she said she’d read the online stories.

The last time I’d visited she said she now knew what I’d tried to tell her.

I thought of him standing beside the bed, this “friend of the family.”

But he never touched my boys, she’d said, digging into the my.

My mother believed in nothing and to nothing was delivered.

While I drove through Pennsylvania near midnight without a place to sleep.

The message said She’s passed.

While firebirds circled the chimney.

Gone as she wanted to be gone.

Despite everything or because of it.

Four sons dead and yet she’d continued.

When I finally slept it was a dreamless sleep.

Fine then, I thought, waking to a ceiling washed by parking lot lights.

Just go.

I see traces of Stevens in almost every poem, beyond the obvious titled poems. I’m intrigued by how you read him “by ear” in your early years, most likely honed by the wonderful sound game “A Few Questions for M” you played with your mother.

JD: It wasn’t until college that I thought much about subject matter. Once I did, I felt a second level of kinship with Stevens. Like him, I have sympathy for both the philosopher’s search for a world that conforms to ideas and the poet’s need for the world to change them and for the world and the poet to be subsequently changed by the imagination. In both cases the real is ephemeral but vital. The actual that “The Snow Man” touches briefly is both vital and insufficient. The imagination falls away; the real arrives. But immediately the imagination begins transforming it again. It is this cycle that Stevens traces over and over.

When you’re deep inside the writing, the world occasionally brings you flowers. My friend Robin Magowan had leant me a journal that contained an essay by Lanny (Langdon) Hammer, whom I’d met briefly 45 years earlier and became reacquainted with through Robin. I’d been remembering New Haven, where I was born and lived for four tumultuous years in a basement apartment on Blatchley Avenue. I’d been tracing on maps and in historical photos walks that my three brothers and I took with our mother in the year(s) leading up to our dramatic escape from our abusive, alcoholic father who was no doubt suffering from what we now call PTSD. Lanny’s essay was about Stevens and New Haven and walking, and it served as permission to write four or five more “Wallace Stevens” poems.

NM: In the title Fearless Now & Nameless, the Now indicates a shift from a fearful “before” and Nameless is that blissful, joyous freedom of anonymity of “the last one standing” running throughout the book. I think of Bachelard’s “there are reveries so deep they rid us of our history, of our name” and this book is like a reverie…. such a curious, intriguing title… do our fears name us, or…?

JD: My early life was governed by fear. A few of the many reasons for that are in this book. No big deal, really, in a world such as ours. Minor, local trauma. But those events were psychologically debilitating, nonetheless. I have overcome some of those fears. For example, all the way through high school, I was unable to speak in front of a class. I’d just sob until the teacher realized he or she couldn’t coach me out of my fear. In my early twenties, to work on this problem, I signed on for back-to-back community radio shows–8 consecutive hours of talking in front of invisible people. Gradually, I got to a place where I could make a living talking in front of people. It turns out I had a lot to say.

Maybe we aren’t so much named by our fears as tattooed by them. I should say here that the character who is “fearless now & nameless” in the book is only a version of a future me, not me entire.

By the way, I’ve always loved Poetics of Reverie by Bachelard. It’s a good thing I didn’t think of that line, or I’d have four epigraphs to consider! But that is what happened in this book. This is as close to a deep reverie as I’ve come since the early 1990s when I wrote the 42-page poetic sequence “The Ochre World.” I also think of a related line Bachelard wrote (which seems also to explicate Martin Heidegger’s “man dwells poetically”): “Consciousness rejuvenates everything, giving the quality of beginning to the most everyday actions.” Lately I’ve thought that as memory wobbles and fails, the world, unburdened of our easy dismissals, our carelessness, begins to shine with newness again.”

NM: Do you consider Fearless Now & Nameless a radical departure from your previous collections?

JD: This book feels like both a progression and a return. There are aspects of it—family poems, narratives, meditative poems–that feel like my first book. There are touches of the disjunctive from my second book, Scrimmage of Appetite, some of the tenderness of Preliminary Report’s closing poems, the eccentricity of Improbable Creatures. the humor of An Amiable Reception for the Acrobat. All of my books feel to me like anthologies written by multiple poets. I don’t have a signature style. I’ve always enjoyed writing in multiple modes, forms, voices. Federico Garcia Lorca is probably a model for that approach. Pablo Neruda. Fernando Pessoa, too. “Inspired by Pessoa, who I began reading in 1983, I write “as” other people, both real (Wallace Stevens) and imagined (Chuck Calabreze). I have three poems–each written by a separate “heteronym”–I have three poems in the new anthology of poetic responses to Pessoa out from Mad Hat press, In the Footsteps of a Shadow.

NM: Can you tell our readers about the Clap the Houses Dark project and terrific album?

JD: Thanks for asking. Clap the Houses Dark is a project that started when the poet, composer, and guitarist Greg Glazner and I spent a week in his Sacramento home studio writing a song called “Over the Transom.” Greg had been working on integrating poetry and fiction into his musical career for twenty years. He had figured some things out by the time I showed up in his studio to write together. He’d started out creating settings for stories and poems, but he was always disappointed by the results. More recently he’d begun composing the sometimes spoken, sometimes sung words along with the music. Suddenly the poems had the pleasure and force of songs. In two of the three lyrics I wrote for our debut album, I returned to the kind of dramatic monologues I’d written in my first book, Dangerous Amusements. This past January, with the help of the poet Tommy Archuleta, we formed Clap the Houses Dark. When we got together for the first time in April, we went straight into the studio and recorded the album. It’s now out on all the major platforms—Spotify, Amazon Music, iTunes, and YouTube. Search for us. We’re the only Clap the Houses Dark out there.

NM: Jon, this interview has been an amazing pleasure, a dazzling embarrassment of riches, a light in this crazy world. Thank you for taking the time away from your busy life to hang out with us at Plume.

After Therapy, I Reimagine Our Life Together as a Series of Movie Scenes

To say disaster is another name for Man is

to generalize from the particular man I have become.

Meanwhile, these dishes are smashable, that door

slammable. Here, I want to stop and say I long

for the time before I became the problem, the trouble

banging on the midnight door, wanting to get

back in, ready to claim, dear Jesus of the skewed paintings,

Muhammed of the crimped Mustang, Buddha

of an emptiness big as a billboard, that I am forever

changed, here in my bedazzled jumpsuit,

my vague hair in a man-bun, my eyeliner a wreck.

After the credits, the outtakes in which I fumble

every important line and you sneeze out your gin fizz,

there is that long silence before the lights come up

in stages, a stale metaphor for my psychological growth.

See, it’s a spectrum, from Lost Cause to Manimal

to Fortress Defended to a dynamo of carefully chosen

“I” statements. Like these: What I hear you saying is x.

Is that correct? As we move from indie drama to rom-com.

From rom-com to a fable filmed in the Australian outback,

desert in all directions and yet we slog inexorably

toward the horizon beyond which we have imagined

a glorious beach, waves breaking green to white froth,

emblems of hope and renewal, though the soundtrack birds

are, ominously, Brazilian. And my newly inscribed

adulting is as ephemeral as words traced across your back,

the I ♥ you, that, in the opening scene, made you turn

and smile over your tanned shoulder, but now

suggests a cutaway to terns lancing the waves

full of hope though they come up fishless again and again.

Is that a fair assessment? Am I reading you correctly?

What I’m feeling from you right now is what the room

must feel at 3 am when the ice maker shudders

and clatters, spilling cubes into an empty tray.

Listen here to music by Clap the Houses Dark

Screenshot

Jon Davis is the author of six chapbooks and seven previous full-length poetry collections, including, most recently, Above the Bejeweled City (Grid Books, 2021) and Choose Your Own America (FLP, 2022). Davis also co-translated Iraqi poet Naseer Hassan’s Dayplaces (Tebot Bach, 2017). He has received a Lannan Literary Award, the Lavan Prize from the Academy of American Poets, a Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown Fellowship, and two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships. He taught creative writing and literature for thirty years, two at Salisbury University and twenty-eight at the Institute of American Indian Arts. In 2013, he founded the Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing at IAIA, which he directed until his retirement in 2018. From 2012-2014, he served as the City of Santa Fe’s fourth poet laureate.

In January of 2024, Davis and poet/guitarist Greg Glazner formed the band Clap the Houses Dark. The band includes bassist Jon Lucero and a roster of drummers including Tommy Archuleta, Mikey Chavez, and Jon Trujillo, who is also the band’s sound engineer. Their first album, Clap the Houses Dark, which mixes poetic language with complex rock compositions, is streaming on all the major platforms.