A Note From Lisa Rose Bradford:

Sadly, Juan Gelman has left us, dying yesterday, January 14th, just one day after I received an email thanking me, in his typically extraordinary way, for my joy and beauty. Though his death is crushing, his poetry will live on, proffering joy and beauty to his readers for generations to come.

And as he is very much alive for me as my friend, I have left him in the present tense in my introduction, as his today will continue to be my present.

Approaching Juan Gelman’s Today

Hoy (Today) is the latest volume of poetry by Argentine writer-in-exile, Juan Gelman. Though selections of Gelman’s verse have been published in more than a dozen languages, the poems of this captivating new work have yet to be translated. Poet and critic Jorge Bocannera recently stated that Hoy is “one of the most revealing works of our times, a sort of Guernica of the written word, […] a showcase of tiny polished gems.” Gelman’s musing on art and justice are composed in a profoundly unsettling manner, exhibiting once again a perception and an artistry that have established him as Argentina’s foremost contemporary poet.

Originally entitled “Condenas” (convictions), these poems were sparked by the sentencing of those who executed his son Marcelo, whose body was found in a barrel filled with cement in the San Fernando River after being “detained” in the clandestine Automotores Orletti center, active during the military dictatorship of Jorge Videla. Each text in this collection forms a different layer of the poet’s present thoughts: the ceaseless pain of losing a son, the ambivalence of justice, the world’s perversity, and the saving graces of passion and beauty.

Appearing in May of 2013, this volume distills the best qualities of the poetics of his 20-plus books of verse published since 1956. These poems are written in a surge of word play, neologism, concatenating rhythms, chiming assonance, unorthodox grammar, and breath-filled slashes. At first sight, one might classify them as prose poems, particularly considering Baudelaire’s “dream of the miracle of a poetic prose, music without rhyme, supple and muscular enough to accommodate the lyrical movement of the soul, the undulations of reverie, the bump and lurch of consciousness.” These meditations are nothing if not supple and muscular, and the extreme condensation of thought and image can only be read from a lyrical mindset. Though they seem to flow toward narrative or scene, expectations constantly “bump and lurch” as the gaps and appositions from sentence to sentence must be sutured by the reader’s imagination.

Questions often drive these texts: “How much blood does it take / to go from knowing to contradiction / from forgetting to horror / from injustice to justice?” and conclude with ironic or enigmatic statements: “To counter reckless death, strings of spittle unfurl against a copy of the bleeding line.” Many of these haunting images are quite startling, bordering on the surreal: “the flight left a dusty dew in the pulse of a child,” and their accumulation becomes vertiginous: “Oblivion founders in movements of desire / the dawn that trembled during combat / the crescent cut by the protracted night re-lifed.” Questioning his own part in history, Gelman composes many lines that wax metapoetic, or perhaps, metajudicial: “The void toils away at its dispossession so a body can become another body, a dazzling word, a labial dizziness.”

The 280 roman-numeraled texts speak to friends, to his dead son, to power, to justice, to reason, with the exception of the closing poem, where Gelman considers once again the potential of the poem:

And?

if poetry were a forgotten memory of the dog that mauled your blood / a false delight / a fugue in me major / an invention of what can never be said? And if it were the denial of the street / horse manure / the suicide of two keen eyes? And if it were just some anywhere that never sends word? And if it were?

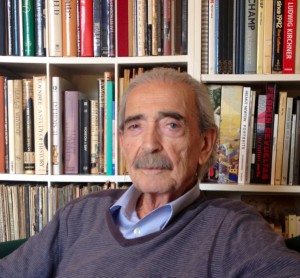

Photo by Paola Stefani

“Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream,” stated Adorno to amend his dictum regarding poetry after the Holocaust, yet how does the survivor find a voice to bear witness to torture and murder? To give voice to memory? To express the barbaric? Certainly not through conventional language; but the question lingers: can verse invent “what can never be said”? Gelman does not flinch; he generates poems of passion, a passion that points to writing as an erotic alliance with the reader.

~ Lisa Rose Bradford

From Juan Gelman’s Hoy, Seix Barral, 2013

Translated by Lisa Rose Bradford

LIX

The cry gathers around a birth that is never quite born. World catastrophes penetrate the mouth and alter its decrees of tranquility. It burns, suffers, belches smoke, offers thanks for what was lost, spent. Gazing at its invisibility it goes blind. Birds full of forest bathe a hand in the sunlight where a rusty caress lies trembling / black star / they can fathom its light.

LX

Some decentered gestures never touch the horizons of the flesh. Nor shrieks, nor the hell that reveals how handsome spectacles cower through the lectures on guilt / nor healthful air nor the order of the parts, that would be love of what is not / so it may be. The harp has fallen silent in a corner full of pleas conversant with their danger. The images are singing, carping, furying in the deflagrations of the words and no one can bring a single facet of the secret back to life. To counter reckless death, strings of spittle unfurl against a copy of the bleeding line.

LXXI

Chance severs the guts of corruption, Power passes by and sutures the gash. Beneath still lie beating the impotence of the poor, alphabets for the ineffable now fled, treaties of a tamed and docile reason. Lying alongside the human rights of the past, those of the present bleed unsheltered. Cruelty claws with capable nails. The country’s chasms paints them red with fingernail polish and its institutions give a standing ovation. The garden watered by Love shudders with fear. What’s the worth of a life not lost in future salts. It preserves its ruins and so survives.

LXXII

The heart’s elastic leap to its never having been performs time’s oeuvres with utter resolve. Who do they think they are those hours gone by? Do they not drag the ebb and flow of a death bereft of bones? Seas that may as well keep them, bring what they may. In the longstanding sadness there is the love that is there, lost flames embrace its affliction. Learn to keep your hands from programmed knowledge, faithless beasts. The vertical axis does not separate the war from the horse, desire from the thing desired, the tender heart from its hardness. We are orphans of letters that can no longer be sent.

LXXIII

When God gathered together all the letters to begin the world, one of them was absent. Faint / she is searching for a mouth as a haven. Not even fasting helps to behold her, ever traveling in her thirst for justice. In the eye she hewed her absence, no decree to found her and no one finds her sound. She shines within, unseen her vertigo where I am cantering in you. Private voids remain invisible, no matter how many edicts are issued. Thought packages get manufactured to ensure more blood on the streets and still one of heaven’s vaults in the prehistory of this night continues to sing. We hunger for the secret of a pain made of wood that we toss into the fire.

LXXXV

Thinking gives shape to a flower that’s a diversion for death. Hand in hand they sit at the foot of the most severe of autumn trees and nowhere else can so much valor fit. Upon the linen tablecloth a bowl of soup falls silent and no one opens the open door. Outside dogs bark beyond their dog and the decisive discourse comes to an end. The moon travels on waters that move from the heart to midnights of the winched, immobile in another winding down.

De Hoy, Juan Gelman

LIX

El grito se organiza alrededor del nacimiento que no termina de nacer. Catástrofes del mundo penetran en la boca y le cambian decretos de la tranquilidad. Quema, sufre, echa humo, agradece lo perdido, fue. Mira su invisibilidad y queda ciego. Pájaros llenos de bosque airean una mano donde tiembla la caricia oxidada/astro negro/adivinan su luz.

LX

Hay ademanes descentrados que no tocan los horizontes de la carne. Ni sus gemidos altos, ni su infierno que enseña cómo los bellos espectáculos retroceden en las lecciones de la culpa/sin aire saludable ni el orden de las partes que amor serían de lo que no es/para que sea. Se calló el arpa en un rincón de súplicas que saben su peligro. Las imágenes cantan reniegan furian en las deflagraciones de la letra y nadie resucita un solo rasgo del secreto. Se derraman hilitos contra la muerte irresponsable en una copia de la línea borrada.

LXXI

El azar corta las entrañas de la corrupción, pasa el Poder y cierra la heridaza. Laten adentro impotencias del pobre, las letras de lo inefable huido, tratados de la razón domada. Al lado de los derechos humanos del pasado sangran sin abrigo los derechos humanos del presente. La crueldad usa uñas buenas. Los agujeros del país las pintan con esmalte rojo y las instituciones felicitan de pie. Tiembla el jardín que Amor regaba. De qué vale la vida que no se perdió en sales del futuro. Cuida sus ruinas y sobrevive así.

LXXII

El salto elástico del corazón a su no sido ejecuta con intención obras del tiempo. ¿Qué se creen las horas que pasaron? ¿No arrastran flujos y reflujos de una muerte sin huesos? Mares que mejor quedárselos, traigan lo que traigan. En la vieja tristeza hay el amor que hay, fuegos perdidos abrazan su aflicción. Quiten las manos del saber automático, animales sin fe. El eje vertical no separa a la guerra del caballo, al deseo de la cosa deseada, al blando corazón de su dureza. Estamos huérfanos de cartas que no se pueden enviar.

LXXIII

Cuando Dios juntó a las letras para empezar el mundo, faltó una a la reunión. Vaga/busca boca que la abrigue. Ni ayunos sirven para haberla, viaja y viaja esperando justicia. En el ojo cavó su ausencia, ningún decreto la establece y nadie encuentra su sonido. Brilla adentro y no le ven el vértigo donde yo en vos cabalgo. La nada propia es invisible por más anuncios que le pongan. Se fabrican paquetes de pensar para que haya más sangre por las calles y todavía canta un firmamento en la prehistoria de esta noche. Tenemos hambre del secreto donde el dolor es de madera y se echa al fuego.

LXXXV

El pensamiento hace una flor que entretiene a la muerte. Las dos se juntan al pie del árbol más severo del otoño y en ningún otro lugar cabe tanto valor. En el mantel de lino calla un plato de sopa y nadie abre la puerta abierta. Afuera ladran perros más allá de su perro y se acaba el discurso decisivo. La luna viaja en aguas que van del corazón a medianoches del sacado, muy quieto en otro acábase.

Lisa Rose Bradford has published three book-length translations of Juan Gelman’s verse, one of which, Between Words: Juan Gelman’s Public Letter (Coimbra Editions, 2010), received the National Translation Award. She teaches comparative literature at the Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata.

Juan Gelman (1930) was born of Jewish Ukrainian parents in Buenos Aires and grew up amid a myriad of languages, acquiring a fascination for words early on in life. Author of more than 20 books of poetry, he has received numerous prizes including the prestigious Premio Cervantes. Having worked as a journalist and a translator in Argentina, Spain, France, and Italy, he is presently living in Mexico City.