In his first book of poetry, Analects on a Chinese Screen, Glenn Mott claims that the most interesting thing about him is that he is in China. I beg to differ. Mott’s China is not like the China others are “in.” It is not place but the perception of place that offers itself as the real. In other words one can be in China, but what that means, what China “is” will be dependent on who you are, what you can decode, encode, process, “take in,” or attend to. Analects on a Chinese Screen was not a tour book, or the Middle Kingdom of a Sinologist, or the frontier of transnational investment opportunities, and not a monolithic state either, but a complex entanglement of layers filtered through a series of shifting proximities, a convex China, one that has been uprooted and redistributed on the page to reveal multiple angles of Chinese interactions internal and external.

Reading Mott’s work we are not asked to untangle China, that trope of an enigmatic or mysterious “Cathay,” but instead to think through the weave of being in relationship with the “imaginaries” of China, from the complexities and subtleties of historical, aesthetic, and ideological palimpsests. Like a linguistic version of Robert Rauschenberg, Glenn Mott’s poetry redistributes these layers as surfaces in order to locate depthlessness, boundlessness within his lines, so that we may draw new perspectives out of the wreckage of old questions.

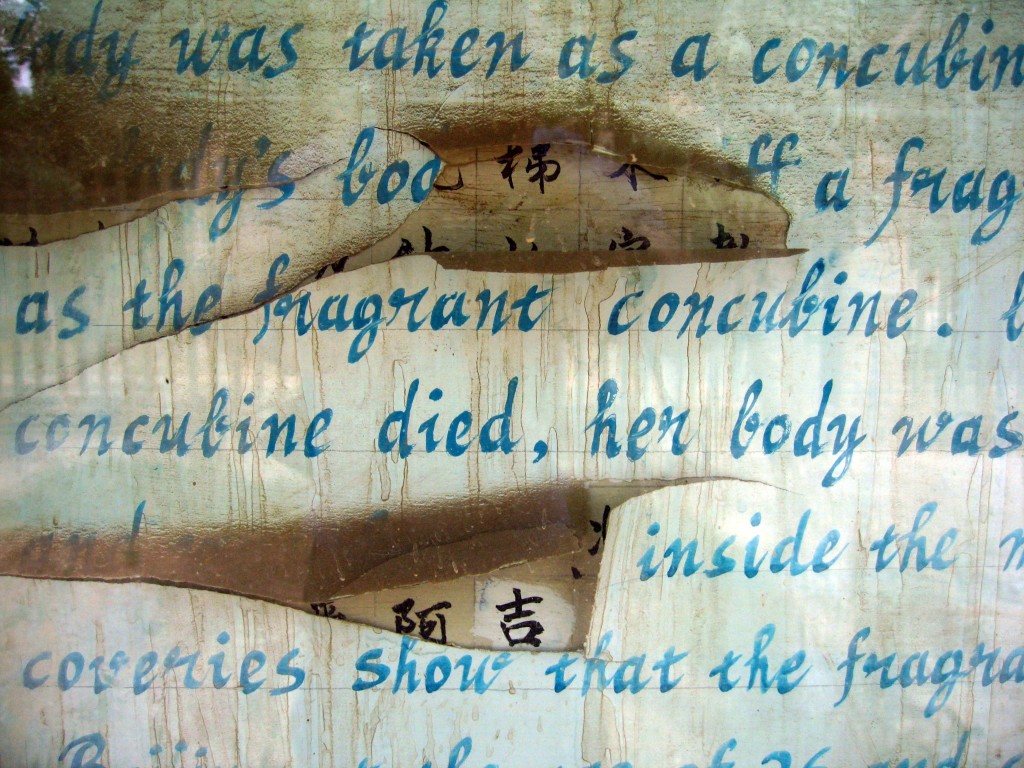

In the present series, Mott not only continues the work he began with his first volume, but extends it considerably. For instance, Chinese and English co-emerge throughout with greater frequency and variation—characters and Chinese phrases pepper the text, sometimes with translations, sometimes without, and in many cases, this reader is not sure if the characters are Chinese or Sinophonic English such as in the line: “In Guizhou we are colored men (白人), pronounced Byron,” but he follows this homophonic play with a piercing ambivalence toward what I see as the transpacific Orientalism of the Romantic tradition: “Spiritual junkies. We are the cold / whites around the yolk.” This language play continues in lines like, “Wǒ is me” where Wǒ (我) is not figured as “me” but is—as it means in Mandarin— “me.” It’s the rendering of a China blues. Such sound play also takes place within his English more generally through a forceful and imaginative use of lineation and pervasive enjambments leading to music we did not hear in his earlier work: “no more. Who conforms to loss / is accepted on a cross. Joy imitates / joy, boy. The way, the way. So says Old Tzu. / And so say I, old Jew with no regret.” There is an unflinching confidence to Mott’s prosody in this series, presencing something about the period between this work and his last book, something that has enabled a new resonance to mature. This assured footing may be most palpably felt in his translations of the Tang dynasty poetry included here. The voices in these poems come through as living poetry—not artifacts—as immediate and resonant, and yet coming to us from a distance that is given the space it needs to be so, like the space the temple bell punctuates in Zhang Ji’s “Night Mooring.”

Finally, it is worth mentioning that this series opens the possibility of a confident spiritual ambivalence—or is it an ambivalent spirituality—for we have poems here that open into such scales and measures but do not close them down into directives or teachings. Take for instance his poem dedicated to the poet Che Qianzi (affectionately known to his friends as Lao Che).

FOR LAO CHE

to turn from reason

is to wake

from the bottomless

intelligent noise

of meaning

to second thoughts

in strangeness

and with error

within elm

an elm

not the shadow

of another season

what is found

goes with itself

to be rid

of reverence

released

on tendril fact

which was there

before attention

I could not quote from this poem without jamming the door halfway open, so I leave it here in full in the hope that, swung wide as it is, the work can be seen as the gesture it is, a space where words open between us, and remain so, as an invitation to walk through.

Jonathan Stalling, 2014

DENY THE ROOSTER

A hundred names in every thousand here is

Wu Ming (无名), pronounced nameless.

In Guizhou we are colored men (白人),

pronounced Byron, or Bái sè de ren.

Spiritual junkies. We are the cold

whites around the yolk.

To those who don’t test me as a piàn zi,

a cheat, I happily pay the foreign tax.

We are treated well

by those who don’t use us as ATMs.

But give what gifts you have.

Sometimes the 白人will be

grateful for conversation.

And that will be worth a higher

price for simple dishes, of salt

and oil, peanuts and cucumbers.

WUHAN GIRL

In every marriage there’s room

for a translator.

I think about that earnest man

and his earnest jottings

who is able to pay for his jawboning

by working on Maggie’s Farm

and will leave it unwelcome

and in abundance

no more. Who conforms to loss

is accepted on a cross. Joy imitates

joy, boy. The way, the way. So says Old Tzu.

And so say I, old Jew with no regret.

In every house there is room

for an old chair that says VE RI TAS.

Do not sit there, brother,

unless you like the truth.

Don’t believe I’ll go back home

I do believe I’ll dust my broom.

And after I dust my broom, any one

of you round eyes, Lord may have my room

I’m goin’ to call up in Wuhan,

just to see if my baby’s over there

Gonna change my name

from Joe to Zhou.

I’ll always believe,

my baby’s in the world somewhere.

DON’T SAY

Still, it all came true

So maybe you’re mad at the truth.

The guy in the lobby who asked

Is this the next one? Don’t say.

He was a prophet.

If you’ll tire of me yet.

The question in that taxi,

If we last that long, I say.

Don’t say let me in again

And I’ll never let you go.

AGENDA

Not long after the end

of the last cultural revolution

I was riding my bike down

some translation of a street

Autumn just beginning, with cooler

nights and crickets wrapping

up their business in the back lots.

I was my own father, then

And wanted no parent to tamper

with my creation.

No father who I am, no

mother that conceived of me.

LIU YUXI, “INSCRIPTION ON MY HUMBLE DWELLING”

The mountain doesn’t have to be high as long as it was climbed by an immortal.

The famous mountain doesn’t have to be high as long as an immortal lived on its top.

The enchanted water doesn’t have to be deep. As long as a dragon lives in it,

it will be enchanted.

This is my humble abode.

Only my virtue makes it smell good.

Only my virtue makes a fragrant house.

Only by virtue does it not smell like shit perfumes.

Traces of moss climb up and make the steps green. Green steps, maybe lichen.

The color of grass enters the bamboo curtain,

Famous scholars stop by to chat and laugh with me.

Among us there are no simpletons and we are all free to be jackasses here.

I can play on a simple zither and read the Diamond Sutra.

No lousy music disturbs my ear. No noise that is not noise.

Doing deskwork deforms, fatigues my body shape.

In Nanyiang there was Zhuge Liang’s hut, sage advisor, chief of staff from Warring States Period.

In Xishu there was the pavilion of warrior Ziyun.

Confucius say, Who the fuck says it’s humble? Where the fuck is the humbleness?

A sacred mountain doesn’t have to be high as long as an immortal lived on its top.

An enchanted pond doesn’t have to be deep as long as a catfish hides at the bottom.

APPRENTICE TO AWARENESS

Thinking was

An early experience

Of gratitude.

My traditions

Leave behind nothing.

To explain them, I forget words

Altogether. And it seems

We have often asked

The same questions.

To live together,

And if necessary,

Use words.

Opening the grammar

Of occurrence to each

Who is there.

TO SEEK A PRONOUN

Working again

in fluency

To turn out focus

letting noise in

Not to travel

without ceasing

And now let’s

look at materials

Letter and white

space for thought

To keep opaque

the inner distance

Where we would

otherwise move.

FOR LAO CHE

to turn from reason

is to wake

from the bottomless

intelligent noise

of meaning

to second thoughts

in strangeness

and with error

within elm

an elm

not the shadow

of another season

what is found

goes with itself

to be rid

of reverence

released

on tendril fact

which was there

before attention

LI BAI, “DRINKING ALONE BY MOONLIGHT”

—after the source in wild grass script

Want a poem fetch a jug

Lift a cup invite the moon

Nip strange on sorghum wine

In the air blossom willows

Drunken Li Bai and the monk

Upstairs takes a pronoun

We are a congress.

Arc light the crescent wires

Bring the crock back home

Put truth to truth.

Ourselves against I double

Wǒ is me that shadow.

Three parables we

And a harsher land

Of sex

For a Vuitton bag

I read or random

Tells of new Spring daze.

Want a moral Confucius say…

Need a poem send your cup

No cadre brother no mistress

We three meet again

Across the river

To tipplers heaven

Mix glad scatter

On starlight row.

EVERCLEAR

getting meaning

after what’s gone

a matter of not

meaning to know

it is plain we are

periodic like the day

through an open

window or gate

and what to have done

having known

what to look for

not knowing

RED WHEELHOUSE

If we are the pure

products

of America,

then

let us go crazy.

If not,

then let us shut

up

about it

and

each have our

reason.

GO

Hold all

See but the return

Constant to know

Not to know constantly

Is too

He who.

She wanted

Everything she could

And was

She felt

So the world

Wishes.

ZHANG JI, “NIGHT MOORING”

Moon down

Troubling my sleep

This night boat drumming

Against Maple Bridge.

First frost then

The quite craven raven

Is a Suzhou crow.

My knowledge was never

particularly actionable.

The kind of work I did

involved no magician.

Fisherman now moving

Light under bridges.

Monk at Cold Mountain

Temple sounds midnight

On the bronze bell.

Aboutness.

Glenn Mott is the author of the book Analects on a Chinese Screen (2007), is managing editor of the Hearst newspaper syndicate, and was a Fulbright Scholar at Tsinghua University in Beijing (2008-09). He has also held teaching posts at universities in Shanghai (1991-93) and Hong Kong (2010). While working in China in 2009 he organized a program at the U.S. Embassy on “Law and Journalism” bringing together two of China’s most high profile human rights lawyers, Mo Shaoping (who represented jailed New York Times researcher Zhao Yan), and the self-taught legal defender Pu Zhiqiang (who is currently under arrest in Beijing for his rights work). The program spurred several more workshops with Chinese journalists and legal scholars in the cities of Guangzhou, Xiamen and elsewhere. Earlier this year he worked with the Academy of American Poets to make Poem-A-Day available in syndication to news publications. He has edited Paul Laurence Dunbar Selected Poems (1997), and is currently working with Yunte Huang on an anthology of modern Chinese literature for W. W. Norton.

Jonathan Stalling is an Associate Professor of English at OU specializing in Modern to Contemporary American Poetry, Comparative Chinese-English Poetics and Translation Studies. He is a Contributing Editor to World Literature Today is the co-founder and an editor of Chinese Literature Today magazine and book series. Dr. Stalling is also the founder and Director of the University of Oklahoma’s Mark Allen Everett Poetry Reading Series and is the author of four books including Poetics of Emptiness, Grotto Heaven, Yingelishi, and the forthcoming book Lost Wax. Stalling is also the translator of Winter Sun: The Poetry of Shi Zhi 1966-2007. Dr. Stalling’s work in interlanguage poetry and translation is the topic of his recent TEDx Talk: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7de8ENdf1yU