Nancy Mitchell: Hi Ani and Luljeta! What a great treat to chat with you both about these amazing poems. Thank you!

Ani Gjika: Thank you and Daniel for the opportunity!

NM: I’m wondering, Luljeta, as you write poetry in other languages do you write in English as well? If so, was there a particular aesthetic objective in having Ani translate these poems?

LL: I have tried to write in English, and I often write a first draft in another language because doing so creates twice the magic. But whether I do that or not, the poem needs to go through the hands of an expert to whom the English language comes naturally. Despite my progress in English, I don’t believe I could ever write in a perfect, vital English. I have wondered why that is and the answer is that at my age, 46 years old, language is no longer an arbitrary connection but a way, a system of thinking which by now has been perfected in the language to which I belong. This system becomes less and less flexible the older one gets. The logical attitude, for example, is so different from one language to another. Particularly, the syntax, which is the skeleton of a language, its temperament. This is why, I think, children find it easy to adapt quickly to another language. If I were twenty years younger then, yes, maybe then I would be writing in English.

NM: Can you two talk about the origins of this collaboration?

LL: I met Ani for the first time in New York City, in January 2010, when my book Child of Nature was first being promoted. What impressed me most at first was that Ani came from Boston specifically to hear me read. Then we met several times afterwards both in Tirane, Albania and in Peterborough, New Hampshire. We had lots of time to get to know one another. I was also one of the first people to read the manuscript of her book Bread on Running Waters which I truly liked and which allowed me to understand her poetic sense. It didn’t take me long to realize that I was dealing with a deeply intelligent woman, who asked a lot of herself and who possessed both a strong literary intuition and a great sense of humor. Very passionate! And it’s not of less importance in translation that we both come from the same cultural background, and in this case, it would be hard for Ani to fall into the typical translation traps.

AG: Gosh, I’m not sure that what Luljeta says of me is true, but as for the sense of humor and passion, I think we’re both cut from the same cloth in that regard and I enjoy our e-mail exchange so much so that translating her has never felt like work for me but more like the very basic, raw form of creative process I crave and am surprised by when I’m writing my own poems. As Luljeta mentioned, we first met in 2010 when I attended one of her readings in NYC. I had discovered her work only a few months before that. I was completing an MFA in poetry at Boston University at the time and was studying the art of translation with Rosanna Warren. For the final project in that class, I translated about twenty poems by three different Albanian poets. Luljeta was one of them. It was a real joy to meet her in person because I admired her poetry instantly, especially when I rediscovered it in my mother tongue.

NM: Your poems put me in mind of the lines The town may be changed/ But the well cannot be changed, from the Wilhelm/Barnes translation of The I Ching; maybe because your poems seem to draw from the primary source, the eternal well of shared consciousness which is impervious to the temporal vagaries of zeitgeist, politics, and boundaries which attempt to, but cannot separate life from life?

LL: Thank you for this confirmation. It makes me feel good to hear it. There’s nothing political in these poems just as there’s nothing clearly defined historically or geographically. And this was done on purpose. Since when I was a child, I have thought that politics are the effect, never the cause. Historical events, just like personal ones, similarly, are results and momentary. They are never enough to build a “literary case” through them. And if we refer to the cause, then we need to search inside the microcosm, inside human nature, which is very complex, unpredictable and existing in all places at once. In another poem, I speak of my childhood curiosity toward broken toys because this was the time when I was free to pull them apart, to split open their guts sort of, in order to understand how they functioned. It’s like being a doctor, who, in order to understand a disease, needs to first find out its origin. And when we go back to the origin, we find we are all so similar with one another… what they call universal.

NM: Wow and yes! We would have been fine childhood playmates; I too, took dolls apart, and when disappointed that I could find no soul, wanted to move on to dead birds in hopes they might reveal it; my parents could only go so far to indulge me.

Am I wrong to intuit that you were born with knowledge of this source, and, when, as a child, your “eye” was opened to it as you write in ACUPUNCTURE, it was this new vision rather than a reaction against/response to social realism, which was the impetus for your first poems?

I was a child when my first teacher

mispronounced my last name twice. That pricked me like a needle.

A small needle in the earlobe. And suddenly

I saw clearly—it affected my vision.

I saw poetry,

the perfect disguise.

LL: Without exaggerating too much, and despite the fact that this has not been proven scientifically, I believe that each one of us inherits a kind of archetype, emotional and informational archives. And some people simply do not rummage a lot through there, but some others do.

NM: I know what you mean; when I was ten I saw a re-release of the movie Gone with the Wind. I remember the stunned moment I realized that every woman was destined to be a Scarlett or a Melanie, and I felt my fate impress itself on my young consciousness as a seal to scarlet candle wax on a love letter

LL: I remember when Naomi Jaffa, The Poetry Trust’s Director after introducing me at the Aldeburgh Poetry Festival last November, asked me, “And how old are you? 900 years old?” You can take that as a compliment, or not, because the attributes don’t belong to me really. In another poem, “Vertical Realities”, I’ve said that “There are three generations inside me/who dictate what I should or should not do”. Survivors, in general, (and it could very well be said that I’m “a survivor” like several others who come from communist or fascist dictatorships) if you really look into it carefully, find it difficult to create an identity because the identity of the group to which they belong is many times more powerful than the one they want to create. Take Hebrew literature, for example. Singer, who is one of my favorite writers, was able to create successfully, in my opinion, the dominant power of survival cultures over the individual.

Whereas the poem which you were referring to above, is an attempt to give an answer through poetic arguments to one of the questions every writer asks themselves: “why do I write?” And one of those answers is to create an identity. Things like Ford cars, Alfredo sauce, espresso “mocha”, all the way to sticky post-it notes – they each have a patent, an authorship, a name. It seems that we’re in an eternal war to survive anonymity, each of us within our own means.

The biographical element in this poem is that I would truly get frustrated when people used to mispronounce my name. And in 90% of the cases this would happen because my last name is difficult to pronounce even in my own language. And terribly long so that it ate up several boxes in the class roster. When I became a teacher myself, I made similar mistakes with my students’ names and encountered similar frustrations in them. Are names so incredibly important to us? But you made another interesting observation when you mentioned, as a counterpoint, “social realism”, because the art of social realism used as a propagandist tool, aimed precisely at crushing one’s identity or, rather, at creating a collective one. And since this goes against human nature, social realism was destined to fail as a movement.

NM: The lines “the perfect disguise” triggered another childhood memory: as a child I was awakened by a thunderstorm to thousands of postage-stamp sized images of byzantine paintings (which I later saw in a college art history class) of the infant Jesus flashing in my room’s dark, while a man’s voice boomed as if through a megaphone “Behold the Rain Fall Upon You.” I should disclaim here that I had seen the Ten Commandments that day—we got out of school to see it; in “living” color, fifty cents admission—so most likely this experience was the product of an inflamed imagination rather than a divine visitation. In terror I kept my eyes shut the entire night, and the next day I felt cast out into rain, culled from any ordinary childhood. Thereafter, I felt a split between surface life and an under-life. For fear of ridicule I never told anyone, but wrote about it poems, “the perfect disguise.” I’m wondering, did you feel similarly isolated with your gift of vision?

LL: Probably not in such a poetic way as it has happened to you. I didn’t even realize that I had a gift until much later. But I remember that when I was little or fairly young, I always ended up alone because of the strange turns I would give to a conversation, turns that were confusing to everyone else. On top of this, I used to always feel a certain melancholy for no particular reason and I’d try to mask it in every possible way so that for some time, I even tried writing funny poems, but this was also a reasonable despair which I believe came to me from the fact that I was often able to see the end result of things before I even attempted to engage myself in them. This was simply a clarity, a clarity that to a certain extent, was unhealthy. Considering my passion for the work of detectives and investigations (I often think about starting to write thrillers) I am convinced that the strength of my creative work is my analytical ability; this is where I need to rely on.

But is there something sacred, something truly divine in poetry? Something that cannot be explained through curiosity, intelligence, or even analytical ability? Building a metaphor is such a pure situation. We could come up with a hundred formulas for a metaphor but none of them can help us create as powerful a metaphor as that of Yehuda Amichai’s, for example. This must be what they call “inspiration”, a kind of holy spirit. Truthfully, luck, a gift.

NM: Am I correct in that this vision has an X-ray quality to it? For example in LIVE MUSIC, bread, universally called “the staff of human life” is full of air holes despite its smooth crust on the outside.

LL: I’m happy to hear that. And I’m grateful for your astute reading. This metaphor is key to this particular poem. I’m talking about imperfections, those we tolerate within a tight circle, within a family, ourselves, but which on the outside become much more challenging. A live pub where neither the music nor the language are original, where the food is of second hand quality and even the voice of the singer is too low, suggests an environment where people have low expectations and this is a safe way to face and deal with existence without feeling sorry for yourself. And in fact, in another poem, I go a little further and use the German word “schadenfreude”, which means “the pleasure derived from others’ misfortunes” which acts as a kind of grease, man’s consolation to accept life as it comes because someone else has it even worse.

Just think how more than half of reality TV shows, programs and movies all around the world suggest a reality of small but achievable goals. Non-dramatic standards. Even on American TV you often find such programs and I know well that this is not an American reality. But such products of the media act as a consolation for a large number of people who feel unfulfilled. And the media sociologists know fairly well what they need to be offering the public.

NM: I’m intrigued by how these poems work as a conversant body. Can you talk about the mirroring of the sudden “vision” of ACUPUNCTURE in CHILDREN OF MORALITY

Moral was easily pointed at by a seven year old’s ink-stained finger,

perfect examples of vice or virtue

there where time lays its eggs on a swamp

and speak to how the last line twists the theory that at seven years a child begins to reason; in this poem, “time” is “where” this “reason” will be hatched from the swamp of the primordial knowledge that archetypes will inhabit a body in every age that needs to lay blame:

Where I grew up, moral had a form a body and name:

a Cain, an unremorseful Mary Magdalene, a Ruth, a Delilah and a Rachel.

to

And strangely, even the second generation didn’t disappoint:

their descendants wee another Cain, another Ruth,

another Mary Magdalene who never grew up;

LL: By the way, finally, while searching on the internet, I found some epitaphs from citizens of ancient Rome and what impressed me especially were the qualities that were considered praiseworthy at the time, like: “man of honor”, “just man”, “devoted wife”, “clean-living”, “dutiful, honorable, chaste and modest”, “never during bitter times did she shrink from loving duties”, “faithful spouse”, “good mother”, etc., and I notice how much the perception of human virtues has changed through time. In our time, we rarely hear of these qualities mentioned as virtues. It seems that virtue, today, has to do more with one’s ability to adapt, the pragmatic aspect of life, than it being a source of inspiration for the community. To put it another way, human virtues today are related to a more horizontal logic, or pragmatic logic than to a vertical one.

And the poem to which you refer, suggests a microcosm, the small town where I grew up where morality was simple, clear, in fact, stereotyped through particular individuals. Outside in the larger world, it becomes very difficult to morally orient oneself because out there people have other goals and relationships take on priority. Even art and literature do not seek heroes anymore, or absolute evil, but the ordinary man, complex and still vulnerable.

And, to continue with the poem: I grew up in a Muslim family, with a religious culture that was interrupted because of communism and despite this, the references (Mary Magdalen, Ruth, etc.,) are taken from the Bible and not from the Koran. So even I have made a pragmatic choice in this case because the reader is more familiar with biblical references even though this is simply a case of naming things.

NM: In THE RAILWAY BOYS, aren’t the boys, before They grow blurry and quiet, in possession of this same “knowing” by essence rather than by name?

“What’s north like?’

“The people wear fur and have blue veins”

“and south? What have you heard?

“People there think with their hearts and speak in gestures.”

I very much love that poem. Why, I do not know, but while I was reading it scenes with Bjork from the movie Dancer in the Dark were flashing across my mind’s eye. If either of you can shed some light on that, I’d be grateful; otherwise I’ll just chalk it up to the power of these absolutely transcendent, magical poems! Thank you both very much for this experience.

LL: Thank you! For me, too, this is a favorite poem. This poem deals with how one’s childhood geography informs and affects the shape of their personality. Are the people who grow up near the sea, near train stations, in places with exits, different from those who grow up in the continental steppe or isolated villages in the mountains? I think they are. In truth, this whole poem has its origin in country music which, when I heard it for the first time seemed incredibly melancholic to me. I would call it an intelligent kind of melancholy. It can be associated with the American prairies, endless fields which make you feel a certain despair about the idea of life which can be read clearly as if it were written on the palm of your hand. Without any turns, surprises or exits. Lives that are recyclable. Endless monotony. This kind of music created this perception for me. Whereas in another poem titled “On the Other Side of the Mountain”, I talk about how people who live on mountains have way more illusions than anyone else, believing that “on the other side of the mountain, life must certainly be better”. In this case, what’s impossible creates hope. On the contrary, living near the water, creates the illusion of the possibility to leave, the possibility of change. So what can we say of people who grew up where the entire world crosses, near train tracks, with the endless temptation to leave, escaping on top of a train? That they have the right to dream? I believe so. I mean that poetry has to do with the psychological impact of one’s homeland, including here also the landscape itself.

JANUARY 1st, DAWN

After the celebrations at last everyone sleeps:

people, TV channels, telephones

and the year’s recently-corrected digit.

Between the final night and the first day

a jagged piece of sky

as though seen from the open mouth of a whale.

Inside her belly and inside the belly of time,

there’s no point worrying;

you glide along with it; she knows her course.

Inside her, you are digested slowly, painlessly.

And if you’re lucky, like Jonah,

she’ll spit you out on an island at some point

along with heaps of inorganic waste.

Everyone sleeps. A sweet hypothermic sleep.

But those few still awake

might hear the melancholy creaking of the wheelbarrow,

someone stealing stones from the rubble

for new walls going up just meters away.

THE RAILWAY BOYS

Of course they’re blonde, all blonde,

but easy to distinguish one from another

through the grease, smoke and coal dust.

They ride the train’s whistle, effortlessly, as though riding buffalos.

They know each whistle’s routine.

From a distance, they can tell which train

rides toward the cold north

and which one toward the south;

which railcar carries mail, addresses in longhand,

and which one passengers riding never to return.

When the freight train arrives,

they hurry to climb on top of wagons, enjoy a piece of sky

lying on their backs on wood logs.

This is only half of the journey; now

they’re closer to the first star than to their homes.

This is the first test of manhood.

Everything else comes later, behind a broken boxcar,

with the girl with rust-colored hair.

Who was she? The first lover has no name of her own

but a baptismal one and a beautiful buck tooth.

Same as the second lover… the third… .

All clothes are excessive for the one prepared

to wear his own father’s clothes*,

they’re excessive for Aaron’s son,

Aaron whom,

the only blasphemy

would keep away from the land of milk and honey.

Of course they’re blonde, all blonde,

the railway boys. For them,

everything is possible. See how the first railcar returns

last, and the last one first,

when the locomotive switches lanes?

“What’s north like?”

“The people wear fur and have blue veins”.

“And south? What have you heard?”

“People there think with their hearts and speak in gestures”.

On hot rails,

the air, like a concave mirror,

magnifies their slim bodies like the words “fur”, and “heart”.

They grow blurry and quiet.

And against his will, each one of them

will marry the wrong girl,

the one whose eyes are full of a long winter.

Among naked trees

it’s impossible to lose the way home.

With time, train whistles died out;

buffalos turned into white, fluffy pups.

And the sleeves of the fathers’ never-worn cloaks

point to a north and south that seem equally impossible.

*In the Bible, God ordered Moses: “And strip Aaron of his garments, and put them upon Eleazar his son: and Aaron shall be gathered unto his people, and shall die there”. As punishment for his blasphemy, Aaron would not see the promised land, but his own son would.

ACUPUNCTURE

Among personal objects, inside a 2,100 year old Chinese tomb,

archaeologists found several acupuncture items: nine needles,

four gold and five silver.

Long before diagnosing the cause,

ancient masters knew

pain is fought with pain.

It’s quite simple: a range of needles pricking your arm

for a properly functioning heart and lungs.

Needles on the feet – to ease stress and insomnia.

A little pain here, and the impact is felt elsewhere

like a country’s administrative capital, outside geographic borders.

Once, a group of explorers set out to plant a flag on the North pole.

At the heel of the globe. In the middle of the Arctic.

And before the mission could finish successfully

a world war had begun.

With scorching helmets, glory quenched thirst.

The impact was felt on the brain; on the short-term memory lobe.

When Russia used ideology as acupuncture – a needle over the Urals,

it impacted the pancreas that controls blood sugar:

America paid tenfold for whiskey through Prohibition

and Joyce’s “immoral” Ulysses

stood in line at post offices waiting to be burnt.

The universe functions as a single body. Stars form lines of needles

carefully pinned to a wide woolly back.

Their impact is felt in the digestive tract. How can you begin a new day

without having fully absorbed yesterday’s protein?

I was a child when my first teacher

mispronounced my last name twice. That pricked me like a needle.

A small needle in the earlobe. And suddenly

I saw clearly – it affected my vision.

I saw poetry,

the perfect disguise.

CHILDREN OF MORALITY

It was the Europeans who taught indigenous people shame

starting with covering up intimate parts,

shame and a need for locks.

Other civilizations were luckier.

Moral was handed to them ready-made from above,

inscribed in stone tablets.

Where I grew up, moral had a form, body and name:

a Cain, an unremorseful Mary Magdalene, a Ruth, a Delilah and a Rachel.

Moral was easily pointed at by a seven year old’s ink-stained finger,

perfect examples of vice or virtue

there where time lays its eggs on a swamp.

And so, I received the first moral lessons

without chewing them like cough syrup;

everything else was more abstract,

under a chaste roof.

And strangely, even the second generation didn’t disappoint:

their descendants were another Cain, another Ruth,

another Mary Magdalene who never grew up;

clichés were simultaneously risk and shelter for them,

like dry snow for Eskimo igloos.

Now I know so much more about morals, in fact, I might be a moralist,

with an index finger pointing like part of the rhetoric.

But without reference. What happened to those people?

A door opened by accident; light broke through by force

and, as in a dark room,

erased their silver bromide portraits

which were once of flesh and bone.

THE DEAD ARE WATCHING US

On the way to the Promised Land

everything set aside for tomorrow would spoil and rot –

mulberries, meat, even water. Tomorrow, to those people,

was a test of their faith.

But nothing was promised to my people

even though they’ve wandered for forty years.

They live in the Present Continuous.

Their epidermis hung on the line to dry.

As soon as they wake up

women turn on the radio; listen to music.

Music has a short incubation period.

As if it were a tumor, a taste for it brings more shame

than bruises on the face.

Nothing lasts for tomorrow.

They are fresh bait for sharks, who,

when wounded,

bite even themselves.

Their measurement is yesterday, tradition. They fear the dead,

“The dead are watching us. Be careful!

During the day, with hands soaked in mortar,

in the middle of sleep, at night…”

They hang a dog tag on their necks, for every occasion,

reduced to three elements: name, number and ancestors’ loans,

so that fate will easily identify them.

Or at least,

they’re grateful when fate brushes past them,

because they could have been Limoz, the hermit,

who used to find warmth in a cave

burning scraps of paper for hours on end,

or Dilaver with Down syndrome written in his eyes and heart.

Their thin skin

cannot bear the joke

of being “the chosen ones”.

But sometimes, on a full moon,

or as it’s otherwise known, “Wolf Moon”

they can see clearly. A moneylender’s fiendish chuckle

broadens their faces.

According to their calculations, what’s delayed today

will certainly arrive twofold tomorrow.

LIVE MUSIC

Nothing consoles you best before sleep

than this pub of cheap beer and live music,

the callous voice of the singer and lyrics

thrown forcefully together inside rima pobre*.

An argument in the corner,

marks the only difference between week days

and Friday night. That and the phosphorescence of free,

platonic sex. What happens on board, stays on board.

At the edge of the table, wet receipts

with a circled digit at the bottom

are indulgence’s shortcut from purgatory to paradise

(not worth questioning any of this).

A sweet apathy of nothingness and a mockery

latches on to the singer.

“Oh man, she started too high, won’t be able to reach the refrain!”

“You think so?”

“You wanna bet?”

when nobody really needs to hear a refrain.

They’re here precisely for the holes

the large holes in an amateur pub,

as inside artisan bread

with its smooth crust on the outside.

Exiting here is even less ceremonial.

Picture exiting a barber shop,

where, sympathetically, after a haircut, according to ritual,

the barber gives you a fresh slap on the neck:

“Get up now,” he urges you, “it’s someone else’s turn!”

*rima pobre: rhyme between words that have the same grammatical structure.

1 JANAR, NË TË GDHIRË

Pas feste, të gjithë flenë më në fund:

njerëzit, stacionet televizive, telefonat

dhe shifra e sapokorrektuar e vitit.

Midis natës së fundit dhe ditës së parë,

një copë qiell i dhëmbëzuar

si i parë nga goja e hapur e një balene.

Në barkun e saj dhe në barkun e kohës,

nuk ka arsye të vrasësh mendjen;

ti lëviz bashkë me të; ajo e di se ç’rrugë merr,

dhe brenda saj tretesh ngadalë dhe pa dhimbje.

Dhe po të jesh me fat si profeti Jonah,

me siguri, dikur do të të teshtijë në ndonjë breg,

bashkë me dhjetëra mbeturina të tjera inorganike.

Të gjithë flenë. Një gjumë i ëmbël hipotermik.

Por, ata të paktë që janë akoma zgjuar,

mund të dëgjojnë gërvimën e trishtuar të qerres

qe vjedh gurët nga një rrënojë,

për një ngrehinë të re, vetëm pak metra më tutje.

DJEMTË E HEKURUDHËS

Padyshim janë biondë, të gjithë biondë,

për të dalluar lehtësisht njëri-tjetrin

midis grasos, tymit dhe pluhurit të qymyrit.

Ata ngasin sirenat, lehtësisht sikur ngasin buajt.

Ua njohin huqet.

Prej së largu e dallojnë lehtë se cili prej trenave

shkon drejt veriut të ftohtë

dhe cili prej tyre drejt jugut;

cili prej vagonave ka postën, adresat e shkruara me shkrim dore

dhe cili prej tyre pasagjerë që shkojnë për t’mos u kthyer.

Dhe kur mbërrin treni i mallrave,

ata marrin vrull dhe ngjiten mbi vagona. Shijojnë një copë qiell

të shtrirë, në shpinë, mbi lëndë druri.

Kjo është gjysma e rrugës; tashti

ata janë më afër yllit të parë se sa shtëpisë.

Kjo është prova e hershme e burrërisë.

Të tjerat vijnë më vonë, pas vagonit të prishur,

me një vajzë me flokë ngjyrë ndryshku.

Kush qe ajo? E dashura e parë nuk ka një emër

por një stërdhëmbësh të bukur dhe një emër pagëzimi.

Dhe as a dyta…as e treta…

Cdo rrobë është e tepërt për atë që është përgatitur

të veshë rrobat e të atit*,

është e tepërt për të birin e Aaronit, të cilin,

blasfemia e vetme

do ta mbajë larg tokës ku rrjedh qumësht edhe mjaltë..

Pa dyshim janë biondë, të gjithë biondë

djemtë e hekurudhës. Për ta,

gjithcka është e mundur. Shihe se si vagoni i parë kthehet

i fundit, dhe i fundit i pari,

kur lokomotiva ndërron kah?

“Si është veriu, vallë?”

“Atje njerëzit veshin gëzofë dhe kanë damarë të kaltër.”

“Po jugu? C’thuhet?”

“Atje njerëzit mendojnë me zemër dhe flasin me gjeste.”

Mbi shinat e nxehta,

ajri, si një pasqyrë konkave

zgjeron kurmet e tyre të hollë dhe fjalët “gëzofë” e “zemër”.

duke i bërë të heshtur e të paqartë.

Dhe kundër vullnetit të tyre, të gjithë ata,

do të martohen me vajzën e gabuar,

atë që ka një dimër të gjatë në sy.

Midis pemëve lakuriqe,

është e vështirë ta ngatërrosh rrugën për në shtëpi.

Me kohë, sirenat u zbutën;

buajt u shndërruan në ca kone të bardha leshtore.

Kurse veriu dhe jugu kullojnë njëlloj të mundur

prej mëngëve të mantelit akoma të paveshur të etërve.

*Në Bibël, Zoti e urdheron Moisiun: ”Zhvishe Aaronin nga rrobat e tij dhe vishja të birit, Eleazarit dhe aty Aroni do të bashkohet me popullin e tij dhe do të vdesë” . Si ndëshkim për blasfeminë e tij, Aaroni nuk do ta shihte më Tokën e Premtuar, por i biri po.

AKUPUNKTURË

Midis sendeve personale, në një varr kinez 2100 vjeçar,

arkeologët gjetën disa objekte akupunkture: nëntë gjilpëra metalike

katër prej ari dhe pesë argjendi.

Shumë më përpara se të analizohej shkaku,

mjeshtrit e lashtë e dinin

se dhimbja luftohet me dhimbje.

Është fare e thjeshtë: për mushkëritë dhe funksionimin e zemrës

ndihmojnë një varg gjilpërash të ngulura në krah

E ato në shputë, lehtësojnë stresin dhe pagjumësinë.

Një dhimbje të vogël këtu, dhe efekti ndjehet diku larg

si qendra administrative të shteteve, jashtë kufijve admistrativë.

Dikur, një tufë eksploratorësh, u nisën për të ngulur një flamur në pol.

Mu në thembrën e globit. Në mes të akullit. Dhe pa mbaruar mirë misioni,

një luftë botërore kishte nisur.

Lavdia shuante etjen me helmeta të nxehta.

Efekti qe në tru; në lobin e kujtesës afatshkurtër.

Kur Rusia përdorte ideologjinë si akupunkturë- një gjipërë mbi Urale.

Efekti qe në pankreas, kontrolli mbi sheqerin në gjak:

Amerika e Prohibicionit e blinte wiskin dhjetëfish.

dhe Uliksi “imoral” i Xhois-it,

priste radhen per t’u djegur në zyrat postare.

Kozmosi fuksionon si një trup. Yjet krijojnë vargje gjilpërash

të ngulura me kujdes në një kurriz të madh leshtor.

Efektet e tyre ndjehen në tretje. Si mund të nisësh një ditë të re,

pa përtypur mirë proteinën shtazore të së djeshmes?

Dhe më pas, veshi. Mësuesja ime e parë

e shqiptoi dy herë gabim mbiemrin tim.Ishte therëse si një gjilpërë.

Një gjilpërë në llapën e vogël të veshit. Dhe krejt papritur

pashë qartë, Efekti qe ne shikim.

Pashë poezinë,

fshehjen e përkryer pas anonimatit.

FËMIJËT E MORALIT

Ishin evropianët, të parët që u mësuan indigjenëve turpin

duke filluar nga mbulimi i pjesëve intime.

Popuj të tjerë, kanë qenë më me fat

Morali u ka ardhur i gatshëm nga lart,

i shkruar në pllaka guri.

Atje ku unë jam rritur, morali kishte formë, trup dhe emër:

një Kain, një Maria Magdalenë e papenduar, një Ruth, Dalilë e Rashelë.

Morali tregohej lehtësisht me gishtin me bojë të një shtatëvjeçari

shembuj të përkryer vesi e virtyti,

atje ku koha i lëshon vezët mbi moçal.

Kështu, pra, mësimet e para të moralit, i mora pa i përtypur

si shurup për kollë;

çdo gjë tjetër ishte më abstrakte,

nën një çati tjegullthyer.

Dhe çuditërisht ata s’të zhgënjenin as në brezninë e dytë:

pasardhësit e tyre,

ishin një tjetër Kain, një tjetër Ruth, një tjetër Maria Magdalenë,

që nuk rriteshin; klisheja ishte njëkohësisht rreziku dhe mbrojtja për ta,

si dëbora e thatë për igloot eskimeze.

Tani di shumë më tepër për moralin, madje mund të jem një moraliste,

me gishtin tregues, si pjesë të retorikës.

Por pa referencë. Ç’u bë me ta?

Një derë u hap padashje, drita çau me forcë,

dhe si në një laborator filmi,

ajo shkërmoqi portretet e tyre në bromid argjendi,

që dikur, mund të kenë qenë prej mishi dhe kocke.

TË VDEKURIT PO NA VËZHGOJNË

Në rrugën drejt Tokës së Premtuar

çdo gjë që ruhej për nesër, prishej, qelbej:

manat, mishi, madje dhe uji. E nesermja, për atë popull,

ishte prova e besimit.

Ndërsa këtyre njerëzve, edhe pse sorollaten për dyzet vjet,

nuk u është premtuar asgjë. Ata jetojnë në të Tashmen e Vazhduar.

Epiderma e tyre e varur në tela për tharje, në oborr. Sapo zgjohen,

gratë hapin radion; dëgjojnë muzikë,

muzika ka periudhë të shkurtër inkubacioni

edhe pse gjëndrrat e saj janë më të turpshme

se shenjat mavi të rrahjeve në fytyrë.

Asgjë nuk mbetet për nesër.

Ata janë mish i freskët për peshkaqenët, të cilët,

kur janë të plagosur,

kafshojnë edhe vetveten.

Masa e tyre është e djeshmja, tradita. U druhen të vdekurve,

“Të vdekurit na vëzhgojnë. Kujdes!” Ditën, me duart me llaç,

në mes të dremitjes natën…

Matrikulën prej inoksi e mbajnë të varur në qafë, për çdo rast,

të thjeshtuar në tre elementë: emri, numri, dhe pengu i të parëve,

lehtësisht për t’u identifikuar nga fati.

Ose së paku,

duhet të jenë mirënjohës kur anashkalohen prej tij,

sepse fare mirë mund të ishin Limozi që ngrohet me letra në një shpellë

apo Dilaveri me sy e zemër mongoloide.

E paretet e tyre të holluara,

nuk e pëballojnë dot gjithë këtë humor,

-të qenit “të zgjedhur”.

Por nganjëherë, në hënë të plotë

ose siç quhet ndryshe në “Hënë Ujku”

ata mund të shohin qartë. Një nënqeshje djallëzore

prej fajdexhiu u zgjeron fytyrën.

Sipas llogarisë së tyre, ajo që iu është vonuar sot,

do t’u kthehet patjetër e dyfishuar nesër.

LIVE

S’ka asgjë më ngushëlluese para gjumit

se ky klub me birrë të lirë e muzikë live.

kallot në zërin e këngëtares, lirikat

e rrasura me forcë brenda rimave pobre*

që derdhen si mishrat, jashtë grykës së korsesë.

Po kështu edhe birra. Një zënkë atje në qoshe,

bën ndryshimin e vetëm midis ditëve të javës

dhe të premtes mbrëma. Dhe fosfori i një seksi të lirë

platonik. Çfarë ndodh në bord, mbetet në bord.

Në cep të tavolinës, faturat e lagura

me një shifër e rrumbullakosur në fund,

janë indulgjenca që shkurtojnë rrugën nga purgatori në parajsë.

(nuk ia vlen t’i vësh në dyshim)

Një apati e ëmbël hiçi dhe qesëndisje

kapet pas gruas që këndon.

“Aha, e filloi shumë lart; nuk e kap refrenin!”

“A thua?”

“E vëmë me bast”,

kur askujt nuk i duhet një refren. Ata ndodhen këtu pikërisht për vrimat,

vrimat e mëdha në një klub amatoresk

si brenda një buke artizanale me kore të lëmuar

që ta bëjnë të lehtë qenien.

Dhe daljen, akoma më pak ceremoniale.

E keni parash daljen prej berberit,

që me dashamirësi pas qethjes, sipas ritualit,

të jep një shuplakë të freskët në qafë:

“Ngrihu tani, është radha e tjetrit!”?

*Rimë e varfër- rimë midis fjalëve të së njejtës kategori gramatikore.

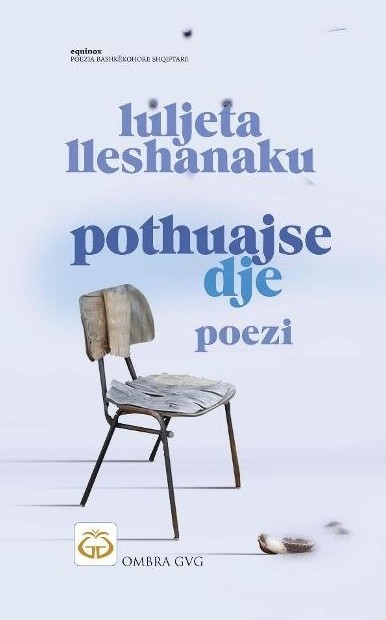

A winner of the Albanian National Silver Pen Prize in 2000 and the International Kristal Vilenica Prize in 2009, Luljeta Lleshanaku is the author of six books of poetry in Albanian. She is also the author of six poetry collections in other languages: Antipastoral, 2006, Italy; Kinder der natur, 2010, Austria; Dzieci natury, 2011, Poland. Haywire: New & Selected Poems (Bloodaxe Books, 2011), a finalist for the “2013 Popescu Prize” (formerly the European Poetry Translation Prize) by Poetry Society, UK, is her first British publication, and includes work from two editions published in the US by New Directions, Fresco: Selected Poems (2002), which drew on four collections published in Albania from 1992 to 1999, and Child of Nature (2010), a book of translations of later poems which was a finalist for the 2011 BTBA (Best Translated Book Award). Lleshanaku was also nominated for the European poetry prize “The European Poet of Freedom, 2012”, in Poland.

Born and raised in Albania, Ani Gjika moved to the U.S. at age 18. She is a 2010 Robert Pinsky Global Fellow and winner of a 2010 Robert Fitzgerald Translation Prize. Her first book, Bread on Running Waters, (Fenway Press, 2013) was a finalist for the 2011 Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize, 2011 May Sarton New Hampshire Book Prize and 2011 Crab Orchard Series Award. Poems and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in Ploughshares, AGNI Online, Salamander, Seneca Review, World Literature Today, Two Lines Online, From the Fishouse and elsewhere.

Nancy Mitchell, a Pushcart Prize 2012 recipient, is the author of two volumes of poetry, The Near Surround (Four Way Books, 2002) and Grief Hut, (Cervena Barva Press, 2009) and her poems have appeared in Agni, Poetry Daily, Salt Hill Journal, and are anthologized in Last Call by Sarabande Books and Make it Sound True, a teaching exercise using sound as a poetic device is included in The Working Poet (Autumn House Press, 2009). She teaches at Salisbury University in Maryland.