Introduction for Up North

Martha Collins

In the fall of 2004, I finished a book-length poem I’d been working on for some years. During that time I wrote almost nothing else; now, on the other side of obsession, I had no idea how to even think about writing a free-standing lyric poem.

I don’t quite remember how the idea first came to me; I thought of sources and precedents only later. But as October approached, I decided I would write seven lines each day of that month; at the end of October, I would have a sequence of 31 little poems, or sections—half-sonnets, I remember thinking, and prescribed for myself a bit of form: the last word of the first would become the first word of the second, and so on.

I created other restraints as well. I was serious about writing each day; I couldn’t skip a day and make up, and I couldn’t skip ahead either. I did allow myself to scribble notes in the top unlined margin of the lined notebook where most of my poems begin, and I could of course revise; indeed, most days began with a close look at what I’d done the previous day. But I followed my own rules; I didn’t cheat.

I intended some thematic connection between the sections, however slight. And it’s also true that there were pressing personal concerns: my mother had died in June, and my husband was having major surgery in mid-October. Mortality was on my mind, and was one of the sources of the title I wrote down as I began the poem, “Over Time.” Of course the title also had a formal source, reflecting the day-by-day manner in which the poem was written.

In 2005 I was busy with final revisions of the book-length poem, so it wasn’t until the end of the year that I again found myself with empty poetic hands. Then, in mid-November, I thought: I will do that month thing again—in December, it would be. And then I thought: I will do one of these each year, in no particular order, until I have completed all the months. That I would finish in 2015 was both scary and exhilarating; it also, of course, assumed that nothing terrible would happen to me in the meantime.

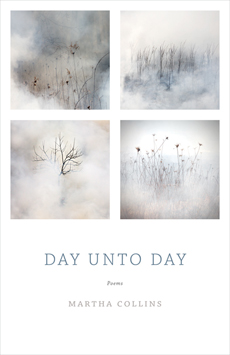

As it turned out, I began moving not quite randomly, but seasonally—October, December, April, July—and when I’d finished those four months, I briefly considered stopping. But I kept going, and after two more months realized there was a completeness to what I’d done. So I put the six poems together, and the result is Day Unto Day, to be published by Milkweed Press in March 2014.

Day Unto Day was not my first working title; at first I was calling the project Daily Meditations. Friends rightly pointed out that such a title might put the book in the religion section of the bookstore (though I wasn’t thinking “bookstore” then); but it had a literary source. I’d been aware, since college, of Philip Pain’s Daily Meditations and Quotidian Preparations for Death, published in 1668; according to the facsimile edition issued by the Huntington Library in 1936, it is “the earliest known specimen of original American verse printed in the English Colonies.” I realized early on that Pain’s little book (including its complete title) was the immediate source for what I was doing, and I was conscious as well of the larger tradition of meditative poetry. That my “texts” were only occasionally scriptural was beside the point: I was trying to do some “soul-making” in these poems, and intended them as a spiritual practice of sorts; I had no intention, in the beginning, of publishing them. It was relevant that the second and final title of at least the first six poems came from the 19th Psalm: “Day unto day uttereth speech, / and night unto night sheweth knowledge.”

As I wrote, I became aware of other sources. The month I began, I remembered, I was teaching Jean Valentine’s The River at Wolf , which features two distinct but intertwining sequences and so many 14-line poems that it’s almost possible to read the book as a sonnet sequence; from there, I think, came my seven lines, my sequencing, and perhaps my spareness. Much later I remembered that one of my students at Oberlin had written several lines each day during December 1997; it’s a pleasure to acknowledge the influence of Jen Liu.

Of course examples of calendric sequences are everywhere, when you start looking. I hadn’t read—and confess I did not in the beginning know about—David Lehman’s Daily Mirror and Evening Sun. And since then the idea of writing a poem-a-day-for-a-month has become so popular that the internet is flooded with blogs recording the poets’ progress. But I was conscious of nothing except poems of meditation when I began.

So where am I now? With Day Unto Day finished, I’ve begun and completed four sections of what I’m tentatively calling Night Unto Night, referring again to Psalm 19. Ultimately, I intend for all twelve months to claim the original “day” title; but for now the second half is a “night” sequence, and it begins with “Up North.”

A word about the poem. My form has changed from month to month: I’ve sometimes written six lines, and I once allowed myself anywhere from five to eight; the way I repeat a word or phrase has also varied. When I began “Up North,” the form changed more radically: deciding for the first time to use indented lines (not just “dropped” lines), I found myself hearing an echo of Williams’ triadic foot, and using shorter lines than I had before. Perhaps this diminishment also reflected the shift from day to night; perhaps I just needed to do something a little different. In this poem, the “repetition” principle changed too: instead of repeating a word, I repeated a whole line from the previous section.

I wrote “Up North” in Ithaca, New York, when I was there as visiting writer at Cornell. The title reflects more about the weather I anticipated than the actual geography: by the map, Ithaca isn’t very far north of Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I usually live. But I put myself “up north” in my meditations, even as I moved from day to night.

from Up North

March 2010

1

Up north is where I think

we go, ghost-trees frozen

with mist, snow

paving the roads, cold

as we will be, no

roads except into

those trees, no road.

2

On a white field, faded

text of weeds:

1 1 1

In the distance, in the dark

of dense trees: little patches,

as we will be, no

more, of illegible snow

3

Distance, in the dark,

disappears: all

is close, closing

in, here

is all there

is, there is nothing

in between, no between.

4

As a skier down

that mountain, I thought,

bird into

that mist, dis-

appearing into that _ _

is all there

_ _

5

That mountain I thought

was a cloud is covered

with snow, snow I thought

to drift into

drips from trees, trees

are going to work

again, drinking in.

6

Earth shifts

its bones, quakes open

again, drinking in

its own, scrawled sign

on fallen wall, dead

body inside -> body

bodybodybodybody

7

My friend is gone, is

body inside body

of earth, sea

of atoms, she is,

her husband said, in a state

of grace and will

be forever.

8

Waterfall sculpted

itself into water-

fall, using cold

to mold itself solid

and still, as if to

be forever

fall without ever falling.

9

Snow is turning

itself into water,

branches once thinned

to diagram lines have lost

their single white sentence,

roofs are setting themselves

free in explosions of snow.

10

Bird tree fills

with black fruit, grackles

empty, fill again

their branches, utter together

their single sentence,

last word a rough creak

of opening air.

11

If bucket comes up

empty, fill again

with all that is

and there’s enough

again: nothing’s not

for nothing: don’t forget

the extended wings.

12

Head as in headway or

headlight on high-

way, way as in

wayward or in the or on

the, onward

with all that is

heading my way

13

Rain all day, slapping

my back, draping my shoulders,

heading the way

I am going, warmed

by the rain of the all of the, why

was I thinking

snow?

14

Snow person, no person, person

of broken of sorry of finishing, what

was I thinking?

No one is shooting my bombing

my hurting my no

one is counting

me out.

15

One is counting, sun

this morning, two

for gorges filling

with snowmelt where two

have fallen, jumped

this month, not counted on no

three, still counting up

16

Instead of black-and-white winter

through my windows

this morning, too

many browns to count:

brush weeds

path fields skin

of the earth

17

Through my windows

brush-stroked clouds

on blue, trees

reddened with buds, fields

with sun, there’s

even a hint of green

on this day for green.

18

Last week a white oval

edged with lace, today

the pond gleams

in sun, there’s

a red-winged blackbird

fanning his tail, and

there, that first robin.

19

Red-winged blackbird,

same top branch, but one

tree down, crow drives

him away. Do I in my tower caw

like that, or do

I wait below

for your love-call, Love?

20

Same top branch, not one

but four, now one

again, my bird

sings his insistent

song, no chittery answer

yet but arriving crows

don’t chase him away.

21

Back with my love

again, my bird

for life, this first

spring day with its baby

green blades, why did we squabble

about nothing when we

are as grass?

22

. . . are as grass

the crocuses, snowdrops, young

coming up from under, but

not the cattle grazing the grass

that fattens them up, not us:

without roots, we grow

only old.

23

Without roots, we grow

up, like daffodils braving

the rain, then down, at last

into those ghost-

trees or (remember

October?) gold

slipping into air.

24

Slipping into air,

then into that gorge

of rushing white water, or

bursting into crude bouquets

of flame: thus the young

of the world we have failed

proclaim our failure.

25

Of my Love, without whom not,

I do not sing enough;

for the world we have failed

I do not do enough:

in this season (I had forgotten,

mea culpa), this season

of penance, I confess.

26

Looking for yellow spring, I found

body: molecules particles:

we are eaters made

to be eaten, I dreamed—

in this season I had forgotten

(mea culpa), this awoke me:

The rest is soul.

27

Friend I loved, body and fine

mind, is gone, her end marked

by shining words even

as speech failed. Her chosen last

words were I shall give

you rest: is soul

afterword, or silence after?

28

Afterwards, the silence after

the words: yard’s

half-blue again

with scilla, little hats

opened into stars, her

words opened my mouth, my

god I was that yard.

29

My red-winged bird still calls

from his tree, but now

(news today!) she-

bird answers, I

open my mouth, my door

for love, my Love for life, so

easy to frame, shut, but it’s you Love, there.

30

News today, with

one to go, as once

before, but bad

this time, death

breathing down my neck, soul

on hold, good (but listen to

those birds!) I was thinking snow.

31

Up north is where I’ve lived

these days, but I have some

place else

to go, my once

and future someone, you, no

one else but you, Love, be

home soon.

Martha Collins is the author of the forthcoming Day Unto Day (Milkweed, March 2014), as well as White Papers (Pittsburgh, 2012) and Blue Front (Graywolf, 2006). She has also published four earlier collections of poems and three collections of co-translated Vietnamese poetry—most recently Black Stars: Poems by Ngo Tu Lap (Milkweed, 2013, with the author). Founder of the Creative Writing Program at UMass-Boston, she served as Pauline Delaney Professor of Creative Writing at Oberlin College until 2007, and is currently editor-at-large for FIELD magazine and one of the editors of the Oberlin College Press.