Oh What Worms They Are: An Interview with Hailey Leithauser by Amy Beeder

Last month I had the pleasure of talking with the poet Hailey Leithauser about sound in contemporary poetry, mortality, “praise of the lowly,” stage fright, and so much else―

AB: You and I have already discussed your admiration for poets whose work is, as, as you put it, ‘unashamedly embedded in music’, and the relative lack of this in contemporary poetry. As a poet known for sound, what are your thoughts about where such poetry stands now?

HL: I want to be very careful how I answer this one because I don’t want to sound like I’m thrashing the many, many excellent poets who do not make music a dominant aspect of their work. Some of my favorite poems rest more on their use of metaphor or narrative or tone of voice than on sonics, so please don’t misunderstand this as some sort of blanket condemnation.

But that said, I am finding what is for me a painful dearth of music – not just formal end rhyme, but internal rhymes, assonance and consonance, anaphora and all those lovely tricks of the trade – in much of what I’m reading to point where it is not unusual to work my way through a stack of magazines or screen a hundred manuscripts for a book prize without finding a single musical poem.

AB: Why do you think that is?

HL: I think it’s because writers have the mistaken idea that music in poetry forces it to be light, or trite, or conservative, that it can’t take risks, as Editors are so fond of saying, or that if the sound is too prominent you can’t say anything, and in this current hideous political climate that’s the last thing people want. Of course, it isn’t true, you can be serious or cutting edge or political as hell and still ring up and down the musical registers. Sound can work wonderfully in a poem for irony or shock or dark humor – I’m thinking of Frederick Seidel, Kay Ryan, Todd Boss, a poet I recently discovered, Jay Hopler, and there are still formalists out there, so there are still plenty of poets for inspiration, but, sadly, you may have to go looking for them.

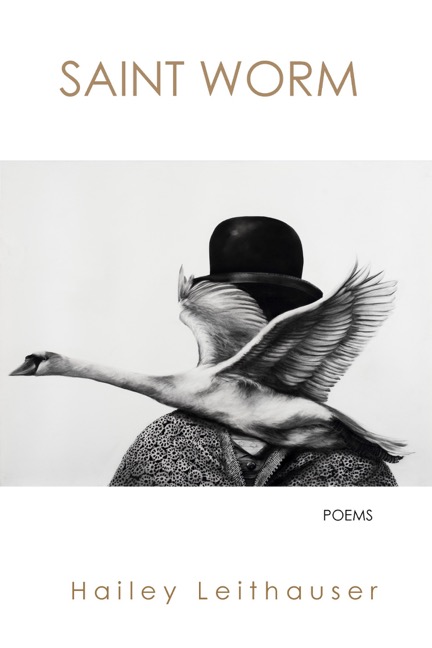

AB: Yes, a feeling that such poetry “can’t take risks,” whereas I believe that music, as an altitude or rhetorical device, only adds more possibilities. Take, for example, “I Shall Name the Worms.” I can’t imagine this poem working—its subject matter, its tension and brilliant dark humor―without your signature use of sound. That poem is from your forthcoming Saint Worm, out from Able Muse this month. What can you tell us about this book―its inception, its process, its cast of worms?

HL: Originally I had written a manuscript called The Cannibal’s Song, which wasn’t quite coming together. I was at a loss for what to do with it, what the book should be, so I decided to simply cut half of the poems, no attempt at a theme, just take the best 50% and see what tumbled out.

It was right after I did this, I was reading Kenneth Koch’s poem, “Fresh Air” and came across his line “Oh what worms they are!,” which immediately set off one of those lovely pyrotechnic bursts in the brain — What a perfect subject because A) I could write a praise poem about the lowly – one of my favorite themes – and B) It gave me justification to write the short, squiggly, irregular lines I so love. I remember I got in the tub to think it over, not a clue what the poem would be about, and while I was soaking away, the first sentence – “I shall name the worms who feast on me: Eloise and Dot, Old Alphonse, and Cecily.” popped into my head out of nowhere. Total surprise to hear these words – I mean where the hell did that come from – but I kept going with it until I had written what still seems to me a somewhat odd and very lyrical poem.

After that more ideas for worm poems came to me, “Saint Worm” because I had always been mystified why people venerated the bones of dead saints, since after all, the power of a saint was all in the spiritual realm, and I imagined their bodies as being consumed more or less by some inner spiritual fire, “Bookworm” because, really, if a word drunk such as myself was going to write a bunch of worm poems there damn well had to be a bookworm in there, “Eminent Worm” because I loved the idea that no matter how powerful you may be, no matter if you are some great Eminence Grise pulling strings off in your ivory tower, the worm always finds a way in, “Coy Worm” because I’m all on board with Marvell’s impatience over his prudish lover, and so on from there.

Once I was well into the process of writing the eight worm poems, I came to realize what I was doing was working out my own sometimes overwhelming, stomach-punching terror of death and I was surprised to find the idea of the consumption of the body being not a destruction, but a release from the body, a de-construction so to speak — That’s what Fuenmeyer’s gorgeous cover art makes me think of, a soul escaping from the body — and that idea was quite comforting. For me that’s the theme of Saint Worm, not death per se, but being mortal, having the knowledge of death, living with that knowledge. Of course not all of the poems are about mortality directly, quite a few are on completely different subjects, but most of them spring from this awareness of it. And since it is a rather awkward subject, death, the only way to write the poems was in a humorous, albeit darkly humorous, tone of voice which is best heightened and expanded by the use of rhyme and music.

AB: Another thread that intrigues me: the songs. “The Cannibal’s Song,” (featured here), “The Pickpocket Song,” and “The Hangman’s Song.” are all spoken by outcasts, who nevertheless find worth—even grandeur—in their occupations. From “The Pickpocket Song,” for instance:

Only we dippers can psalm such a trilling,

cash-clips and coppers, all harmony belling.

Keen-fingered lifters, join in with them

each bracelet, each necklace, each pearl-circled pin,

topaz and lapis, square perfect carats

swearing their ritzier whisper and pitch

over and over the nimble thumb-catch

Noble this music, good, noble, and able.

Grandeur for soul, chums, glad glory for table

Add to that (throughout the manuscript), snakes, toads, a monster, a sin-eater, twice-eaten Tolland Man, and of course, all the worms. Can you speak a little about your predilection for the worthy outcast or abject?

HL: Yes, yes, what I referred to before as “praise of the lowly” – I do love to write those poems! They’re so much more interesting to write than about pretty little things, things that have been exalted and admired right into the literary poor house.

I can remember the exact day I learned this; it was when I first started writing again and I had gone to the seahorse exhibit at the National Aquarium in Baltimore. I spent the whole afternoon ooh-ing and ah-ing over these lovely, lovely seahorses and sea dragons – elegant, lavish, exotic – and all I could think about was what wonderful poems I would write about them, and then I got home and… nada. Everything I came up with was clichéd and boring and stale. I ended up instead writing three pages of rhymed couplets about a freshwater gar.

And, truth be told, I think people identify more with a gar or a crow or a pickpocket than with a gladiator or a gazelle. Plus, most importantly, the language is so much more powerful when you’re talking about that sort of thing; the subjects better lend themselves to the richness of Anglo-Saxon speech, all those gorgeous gutturals and open vowels. I recently had a longish poem about frogs in the Connecticut Review where the frogs got to “wheeze and jug / and whoop”… “throb / and chirrup and croak” – Try getting those kind of sounds into a poem about a dumb old butterfly.

AB: Do you find that meaning, then, is inherent in sound?

We all have visceral reactions to sounds, and there is information, emotional data, inherent in those reactions. There’s a reason that the word for spring is “spring” and autumn is “autumn,” that we skip, leap up, and are dragged, bogged down, that a slap is quick and sharp while a wallop is longer and deeper, that a skink skitters quickly and a walrus waddles slowly. Just think about the verbs associated with a bell – it can tinkle, it can peal, it can knell, it can toll – completely different emotions because of the way we physically react to these words. Cheerful vs joyful, pondering vs musing, awkward vs clumsy — there are shades of meaning in the sounds and it’s the most effective way to make someone experience a poem the way it should be experienced — the frantic shock of the ball turret gunner who “woke to black flak,” daffodils which “Out-did the sparkling waves in glee,” the autumn guest who “walks the sodden pasture lane.”

And you can also use these effects unexpectedly, surprise the reader by using happy sounds where you would expect sad ones, or mix heavy words in with light ones to create ambiguity or tension, a feeling that something is not right as Plath did in “Tulips” when she wrote that the nurses “bring me numbness in their bright needles.”

This all seems almost too obvious to talk about, such basic stuff, that you’d think it shouldn’t have to be mentioned, but so often I see poets, especially newer poets, getting too concerned with some set of specific facts they want out there, focusing on literal rather than poetic accuracy, and forgetting to let sound do some of the heavy lifting for them.

AB: I’m also a big fan of your first book, Swoop. What was it like to win the Emily Dickinson Award? Did it change things for you?

It was unbelievable, a complete shock. I remember I missed the phone call because my cable had been down all day – fucking Comcast – and then about 5:00 it came back up and I heard the voice mail from Stephen Young at the Poetry Foundation that he’d been trying to reach me and would call back the next day. It didn’t even occur to me it was Swoop, they hadn’t sent any kind of finalist notification. I thought maybe one of my poems in the magazine had won one of their annual awards so I called Sandra Beasley – she’d won their Friends of Literature Prize a few years before — and asked had they phoned her to let her know. She immediately said No, it’s the Emily Dickinson, you’ve won, but I didn’t believe it; after so many finalist and runner up spots, it was an impossible dream. Then about 9:00 the phone rang and I saw it was Stephen again and I knew, calling that late, that I’d caught the brass ring.

As far as how it changed things for me, I’d been publishing pretty steadily for a decade – I’d always been lucky with magazines, even in the beginning — so there wasn’t much difference there, but finally getting my first book was huge. Back then I was a coordinator for a local reading group, Café Muse, and every month I’d be meeting and having dinners and drinks with wonderful writers and we’d all be schmoozing along, the visiting poets and some local writers and me and I’d be the only one without a book and I felt like I should be off eating at the kids table. The other writers never made me feel that way, but Lordy, did I crave that external validation. So it was a much, much needed boost for my self-confidence.

And one thing that did change significantly was giving readings, traveling to give readings. That’s always been an issue for me, I’ve had terrible stage fright in the past – the first reading I ever gave was at the 92nd Street Y when I won the Discovery. I’m sure there was over a hundred people there, maybe two hundred, including my father, and when they called my name, I couldn’t go on. They had to put the next poet on in my place while a couple of the sound crew back stage patted my hand and helped me to stop hyperventilating. Even now I have to read first on the bill or there’s a real danger I won’t be able to get up on stage, and I always have a drink right before I get up, but when Swoop came out I felt I had a responsibility to Graywolf to get out there and help promote it, so I had to start dealing with that. I think I gave a dozen readings the year it came out; my favorite was when Rick Kenny invited me to Iowa to speak to a class and give a reading at Prairie Lights. I loved reading there, the energy of the place, so I’ve learned it doesn’t have to be pain and agony every time.

AB: What are you reading now? More than one book? Are they piled are your bedside table? Do tell.

HL: Piled on my bedside table? They’re piled on just about every flat surface in every room in this house — I’m talking Collier Brothers territory – piles on three dressers, two desks, a coffee table, kitchen island, end tables, they’re in every room, every bedroom, the kitchen, family room, living room, my office, in closets, even the master bath.

I do have an excuse. A friend of a friend works for a major newspaper and they receive and discard hundreds of books a week, she says they’re scattered all over the floor, so she culls out all the poetry books and some others she thinks I might be interested in and every week I get a supermarket sized bag of them. And since a lot of them are review copies I can’t pass them on to books stores or Value Village, and I can’t make myself toss them in the trash. Every time I pick one up to throw it away I think about the hours of agonizing work the author went through to make that book happen and I just can’t do it. And so the piles grow to the sun.

But as to which ones I’ve ordered myself, or I’ve set aside to investigate, on the top of the pile next to the bed, I have Carruth’s Toward the Distant Islands, Natalie Shapiro’s Hard Child, Goldbarth’s The Love and Wars of Relative Scale, Jane Houlihan’s The Mending Worm, Reckdal’s Nightingale, and the current issues of Agni and Parnassus. Oh, yes, and a book whose cover I saw on Facebook, The Impatient Virgin, an old potboiler from the 30s that I bought just because I want to frame the cover.

AB: With Saint Worm coming out this month, are you working on anything new?

HL: Two of the poems published below, “Glove Song” and “Splitsville” are from a new ms I’m having a lot of fun working on, a collection of love poems entitled Glove Shove Dove.

*Release date is September 27 2019 from Able Muse.

Splitsville

Let’s dodge this popsicle stand, Pollywog,

let’s make the slip like an Exxon oil slick,

like the mud-slapped shanks on a milkshaked nag,

like a popped ragtop up Route 66.

Why not drop drapes on this hick whistle-stop,

I’ve got an AWOL itch, swoop-the-coop jerk,

a hit-the-bricks drift to leg out the map,

to shudder the dust of this one-plug burg –

and not strolling stag, but with plum boojum,

so chalk your Hancock, my bored paramour,

to warm my arms down a bare thoroughfare;

be my fleet coquette, thief-thick on the lam,

from mean streets to easy, high hog and scrub,

clinch-fit, canoodled, till hoof-it is run.

Glove Song

Adored One, here is

my cheek, sallow

and cold and ready

for scolding, Treasure,

here is my mandible

that waits to be

swatted a bright

candy apple. My

Soft One, My

Hare Down, here tickles

a heartbeat, where

are your pistols? O

Fawn Skin, My Supple,

the moon’s in her velvet,

she’s gracing the lawnleaf,

Cherished, Lost Mammal,

I’m pacing the dawn light,

my hand stands alone.

Arrhythmia

The heart of a bear is a cloud-shuttered

mountain. The heart of a mountain’s a kiln.

The white heart of a moth has nineteen white

chambers. The heart of a swan is a swan.

The heart of a wasp is a prick of plush.

The heart of a sloth gathers moss. The heart

of an owl is part blood and part chalice.

The fey mouse heart rides a dawdy dust-cart.

The heart of a kestrel hides a house wren

at nest. The heart of a lark is a czar.

The heart of a scorpion holds swidden

and spark. The heart of a shark is a gear.

Listen and tell, thrums the grave heart of humans.

Listen well love, for it’s pitch dark down here

*From Saint Worm

The Cannibal’s Song

Today I found some flowers, three, in a row.

Yellow, yellow, yellow.

How poetic it made me feel, all that sunlight pouring

evenly into their beggars’ mouths, into the brave, beggarly

cups of their hands.

Another man or woman might have walked on past,

not stopping to notice the mouths,

not stopping to notice the hands,

interested only in her own internal life,

biting his lip against the yellow brightness,

however,

as I may have mentioned, I have the soul of a poet.

Love of the world fills me like rain fills a battered rain barrel.

So much love that I carry a small knife wherever I go,

so much love I carry a small, silver fork, a spoon,

ornate and profound cutlery spilling from my pockets,

napkins, salt and pepper shakers, a Murano glass,

graceful to the hand, etched with shepherds and cloud-colored lamb.

*From Saint Worm

I Shall Name the Worms

worms are the words but joy’s the voice

– ee cummings

I shall name the worms

who feast on me:

Eloise and Dot,

Old Alphonse,

and Cecily.

What shivaree

this mob shall see!

– my lithesome Dot

and spotted Eloise,

and kicking off

his crutches, what

palatial bacchanal

for Old Alphonse

with never far behind

divine,

intemperate,

dear Cecily.

They will have

a tambourine

or three,

a painted set

of antique

castanets

and emblemed

bugles bright

as winter sun.

Their dance

will start, for once,

at one

and last until

it’s time for tea when

they may pause their

clubby folderol to

ask,

I wonder what pool sap

has set us

to this task –

a secretary, cook,

a cop, a cellist,

a micrologist?

And

did she

ever dance as we

or sing or fling

her questions at the stars

with eyes as wide

as plum jam jars?

Did she often stop

at evening light

to watch a bat

or laugh beneath

the gentling

of a trembled willow

tree? Did she

place love in

her palm, or did

she roam in rain

alone?

The moon will rise,

the sea will sigh,

the freckled smile

of Eloise will widen

as she chomps,

and Old Alphonse and Dot

will flap their gums

in a confederate

fair harmony

echoed by a single,

softened

afterthought, wafting

late, one half-

flat note,

unshepherded, almost

unheard

and unperceived,

from tiddled,

gassy Cecily.

*From Saint Worm