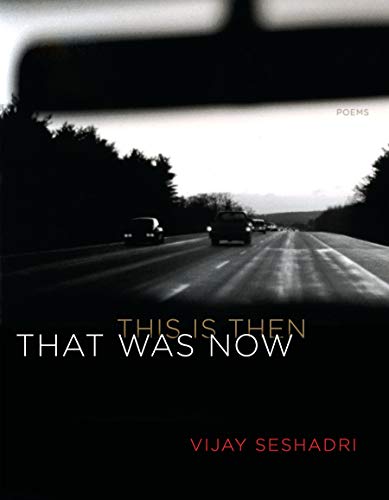

On That Was Now, This Is Then by Vijay Seshadri

John Wall Barger

Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf, 2020. 80 pages. $24.00.

“Eternity,” Heraclitus wrote, “is a child playing checkers; a child’s kingdom.” Nietzsche responded, “And as the child and the artist plays, so too plays the ever living fire, it builds up and tears down, in innocence—such is the game eternity plays with itself.” In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche outlined three progressive stages of human development: camel, lion, and playing child. The camel carries a burden, the lion howls in wrath. The playing child, for Nietzsche, is the culmination of the human spirit. Once the playing child stage is achieved by an individual, the disruptive, illogical, natural, innocent force of play can be used as an powerful instrument to disrupt traditional values and modes of operation within culture.

Vijay Seshadri’s fifth collection, That Was Now, This Is Then, is restlessly ludic. He mercilessly satirizes his fellow humans, including himself. His poems play with form and meaning and rhythm and tone, making the reader work to arrive at ambiguous, complex resolutions. Even the book’s title, with its inversion of “now” and “then,” promises a mischievous game. Often philosophically distant, with an unreliable “I” voice, the poems can be ironic, arch, witty. But then, as with the elegies in the second part of the book, they can be surprisingly heartfelt. Nietzsche’s playing child contains two important characteristics: first, he builds and destroys; second, he’s free of moral ends. Seshadri’s poems, too, build spaces just to disrupt them. Never sententious, the poems seem to be enjoying themselves, turning on a dime from funny to serious, as if these were not separate categories. “Man,” Heraclitus says, “is most nearly himself when he achieves the seriousness of a child at play.”

Some of Seshadri’s poems work like fables: short tales of non-heroic protagonists dragged into mysteries by supernatural visions. But Seshadri prefers ambivalence to fable-like moral lessons. A speaker moving through the city is piqued by something he sees, leading to existential questions about love, hate, God, being, the universe. In “Trailing Clouds of Glory,” from Seshadri’s last book, Pulitzer Prize-winning 3 Sections, the speaker, “on the F train / to Manhattan,” watches a poor undocumented Guatemalan family. Their son, a boy of three, scowls at his family, reminding the speaker of his own son: “when my son came out of his mother / after thirty hours of labor—the head squashed, / the lips swollen, the skin empurpled and hideous / with blood and afterbirth.” Seshadri, while addressing the bad treatment of immigrants in America, playfully disrupts the narrative of the poem. The child—who, in the language of the poem, is both the newborn son and also the Guatemalan boy—speaks in “a voice like Richard Burton’s.” Also, rather than the trite maxim of a fable, the child voices a barrage of wrathful wisdom from Shakespeare and Wordsworth.

Similarly, some poems in That Was Now, This Is Then begin with a Seshadri-like speaker, then take figurative, comical detours. “Robocall” opens with the speaker struggling to write, interrupted by his phone. It turns out to be a call from the supernatural, “the 1-800 voice of the One,” that says, “If I am He or She or They Who are here / when the last star hisses out, why am I talking to you? / I was thinking of you this morning, but why you? / Para español oprima número tres.” The speaker laments, “When will they just let me sit under my guava tree?”

In “Enlightenment,” Seshadri creates a spiritual fable reminiscent of Prince Siddhārta’s renunciation. A renunciate believes that lasting happiness can’t be found in the possession of material wealth or power or fame, so they give it all up and seek answers elsewhere. Seshadri parodies his renunciate, perhaps all renunciates, for going overboard in search of meaning through religion.

‘It’s all empty, empty,’

he said to himself.

‘The sex and drugs. The violence, especially.’

So he went down into the world to exercise his virtue,

thinking maybe that would help.

He taught a little kid to build a kite.

He found a cure,

and then he found a cure

for his cure.

He gave a woman at the mercy of the weather

his umbrella, even though

icy rain fell and he had pneumonia.

He settled a revolution in Spain.

Nothing worked.

The world happens, the world changes,

the world, it is written here,

in the next line,

is only its own membrane—

and, oh yes, your compassionate nature,

your compassion for our kind.

The renunciate—like Buddha, who, after leaving his palace, lived the life of a wandering ascetic, longing to be of service—wanted to help people. He taught a child to make a kite; gave away an umbrella; resolved a revolution in Spain; “found a cure, / and then he found a cure // for his cure.” Unfortunately, “Nothing worked.” The poem ends elliptically, without a clear sense that the renunciate has helped anything. Is wanting to help an end in itself? A kind of redemption, regardless of effects? Perhaps, the poem suggests, enlightenment is just a matter of giving over to the world. Not fighting it. After all, the source of compassion is the world, not humanity. No matter what you do, “The world happens.”

In “The Estuary,” Seshadri again takes aim at our human obsession with making meaning. The poem begins with a brown bear on a salmon run. The bear, “furred like the forest from which he emerged,” lives a holistic, undivided existence. The bear is integral to the world: “Creation impinging on a consciousness / clear and crystalline.” Then the poem shifts abruptly to the world of humans:

Stay down on the pavement where you just fell in a heap

like a bag of laundry, just stay there. Move even a

little and you might damage something else.

You’ve already done plenty of damage.

Stay down, supine. Stay down,

and let the giant buildings loom over you, let them

in their abstract imperium stun you with their indifference.

Wasn’t that the reason you built them in the first place?

Seshadri is satirizing human arrogance. Aristotle, in his History of Animals, created a hierarchy of nature which had a powerful influence on the western notion of humans’ rightful place in the world. He ranked all beings on a scale of perfection, from minerals to plants, animals, humans, and gods. Humans fell below the gods but, of course, above animals. Animals have a “sensible soul” but can’t make meaning or form beliefs. What separates humans from animals is their “rational soul,” their ability to use reason. But, Seshadri seems to ask, where has our fanatical reasoning gotten us? In “The Estuary,” the human creates damage every time he moves. Unlike the bear, the human is overwhelmed by his environment, the “abstract imperium” of the buildings above him. He tried to master nature and could not. So he built a city, a space he could control, but now cowers with anxiety and powerlessness beneath it. Seshadri’s image of the pathetic man on the sidewalk “in a heap / like a bag of laundry” echoes Lear’s vision of a human as “a poor, bare, forked animal.”

“Mir ward alles spiel,” says Nietzsche. To me, everything is play. But perhaps for Seshadri there are limits. In “To the Reader,” the final poem of That Was Now, This Is Then, he seems to let down his guard, leveling his gaze at us readers. The poem describes a potential communion between writer and reader: “I’m writing this so I can tell you that what you’re thinking / about me is exactly what I’m thinking / about you.” Seshadri—perhaps responding to the ongoing debate on the relevance of poetry in our alienating world—points out the deceivingly simple potency of reading as an interpersonal connection through imagination. “What you’re reading is exactly what you’re writing, / by the light of a taper, deep inside yourself, / at your walnut secretary.” He’s proposing a kind of poetic Eucharist: “We correspond 1 to 1, and there is a grandeur in this.” Such grandeur echoes the profound, shared delight that abounds in Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights. The poem, any poem, provides a communal space between people. Through art we meet, outside of time, on the page. In our lonely estrangement, such a bond between people can be a balm for our loneliness. “What if,” Ross Gay asks, “we joined our sorrows, I’m saying. / I’m saying: What if that is joy?”