I had the pleasure of interviewing Reginald Dwayne Betts in a conversation that ranged from poetry, race, and erasure to Dunbar, Du Bois and Mos Def. We talked about prison, the language we use to describe it, and what happens when we frame the narrative of incarceration as being singularly “rooted in the experience of black men.”

AN: I’ve been thinking a lot about the title of your latest book, Felon, which was just published last fall. You’ve written a memoir and two previous books of poetry, all of which explore, in their own ways, what it means to be convicted of a felony, what it means to have been incarcerated at a young age and for a long time, and what it means to live in the aftermath of all that—and to have to keep answering for your mistake despite your many professional and creative successes.

In a 2018 essay for The New York Times [https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/16/magazine/felon-attorney-crime-yale-law.html], you wrote about coming home from prison and trying to keep quiet about it, “as if,” you wrote, “muteness could save me.” Instead, you found yourself having to tell and retell the very story you said you wanted to erase. What does it mean to you now, to be able to claim that word, “felon,” as the title of your book?

RDB: I’m not sure. The title of the book works with the artwork and the poetry. Juxtaposed with the art, the word felon says something about erasure, about loss, racism. There are levels that I’m hoping to explore.

And then, the poems in the book, the crimes and tragedy and loss and love and all that other stuff, that’s me hoping to reveal the lie of a word like felon. We imagine it characterizes people fully, but it fails. And if people recognize their life in moments of this work, their loves in moments of this work, their family and neighbors, then I’ve succeeded. If you read this work and it all still feels so much like the account of the other, I’ve failed.

AN: You mention the cover artwork by Titus Kaphar from the Jerome Project, a series of oil portraits of incarcerated men named Jerome who shared the same first and last name as the artist’s father. In the portraits, the person’s face is covered in tar, the amount of which roughly corresponds to the amount of time they spent in jail.

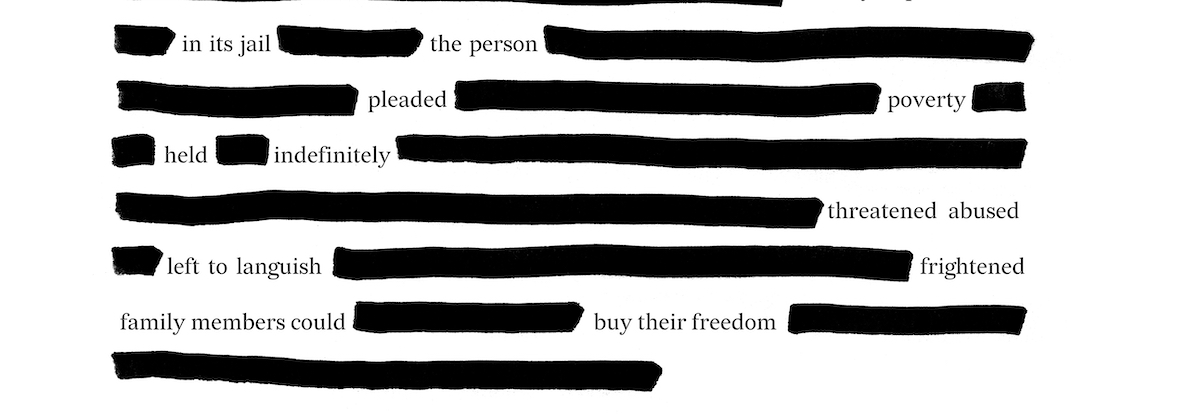

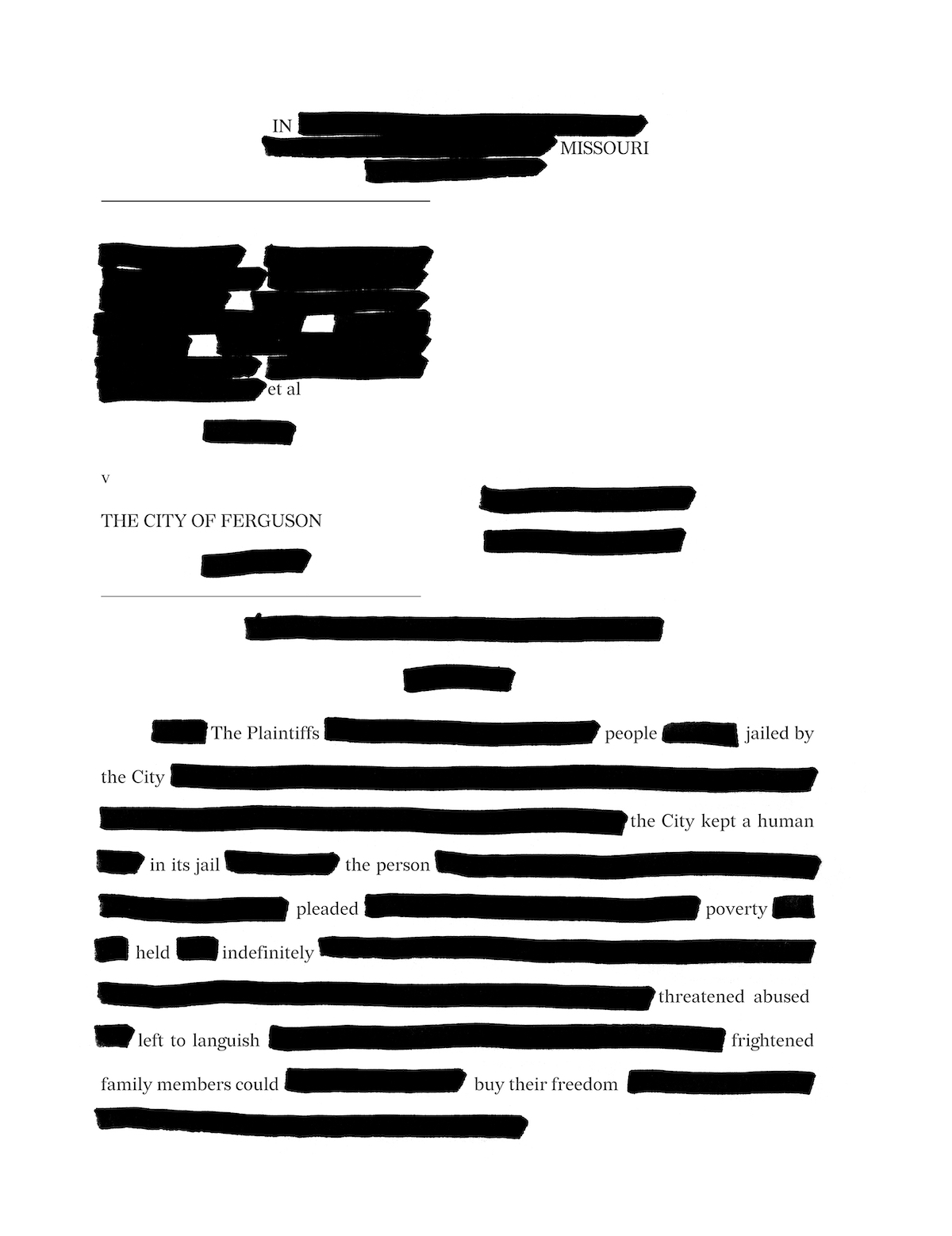

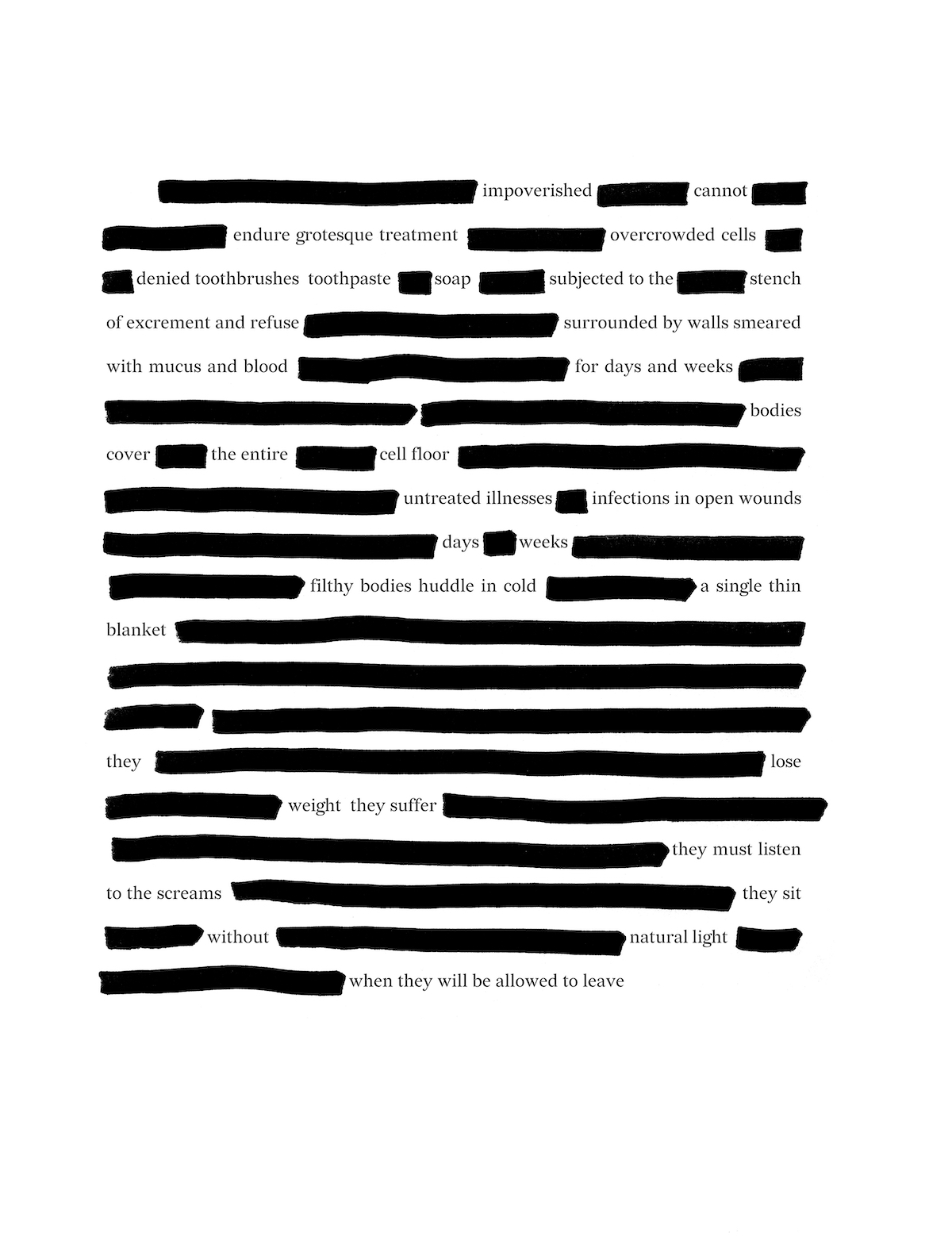

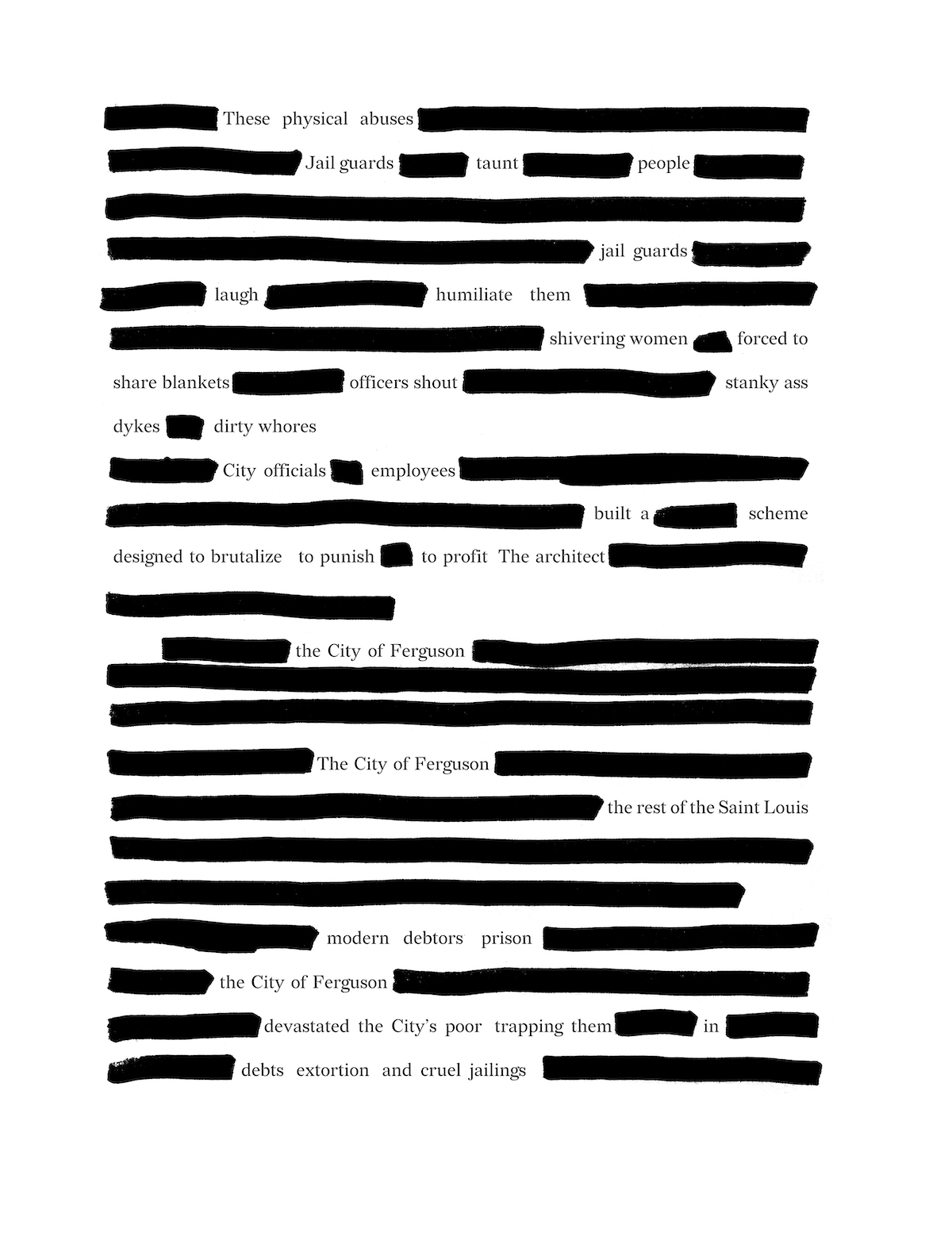

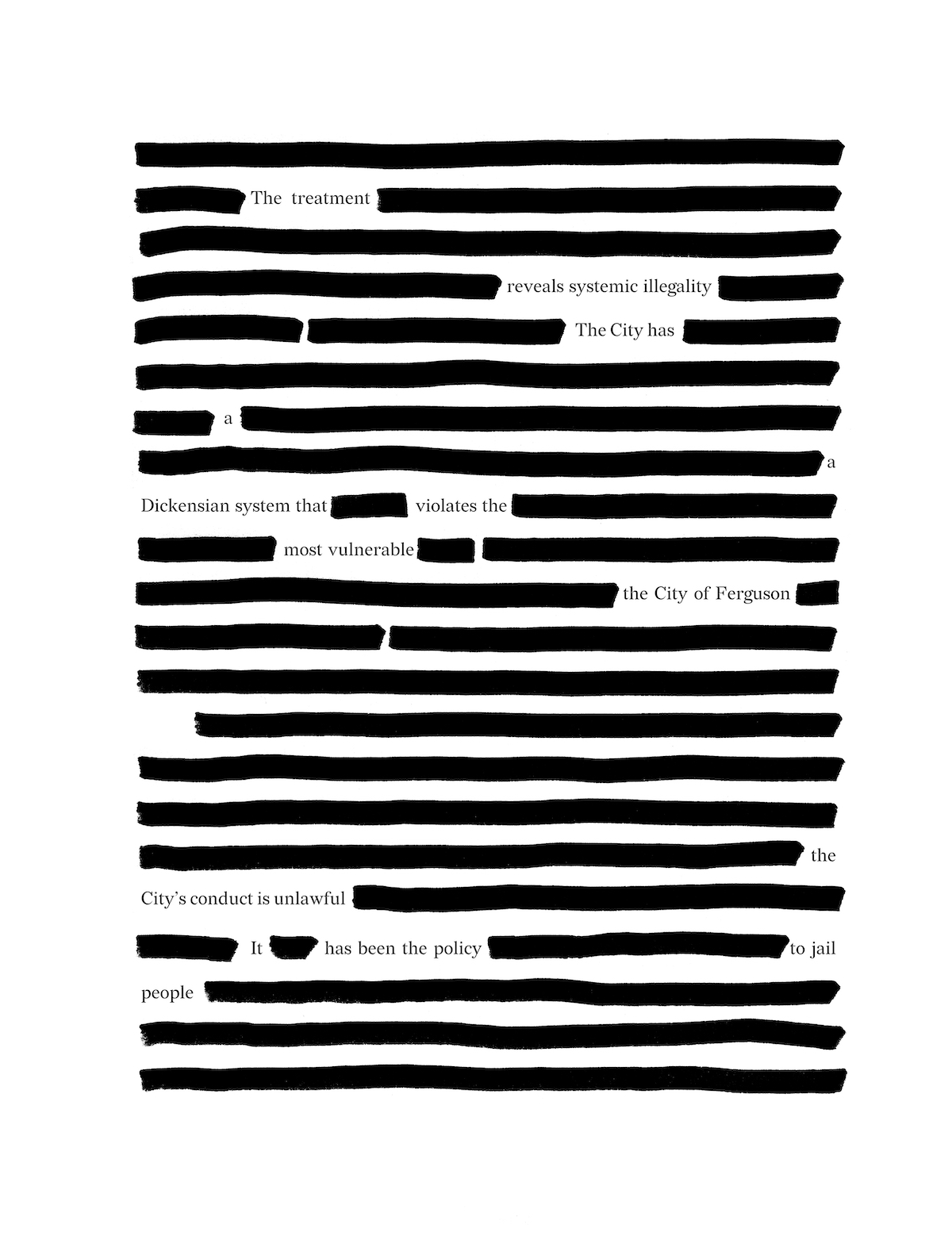

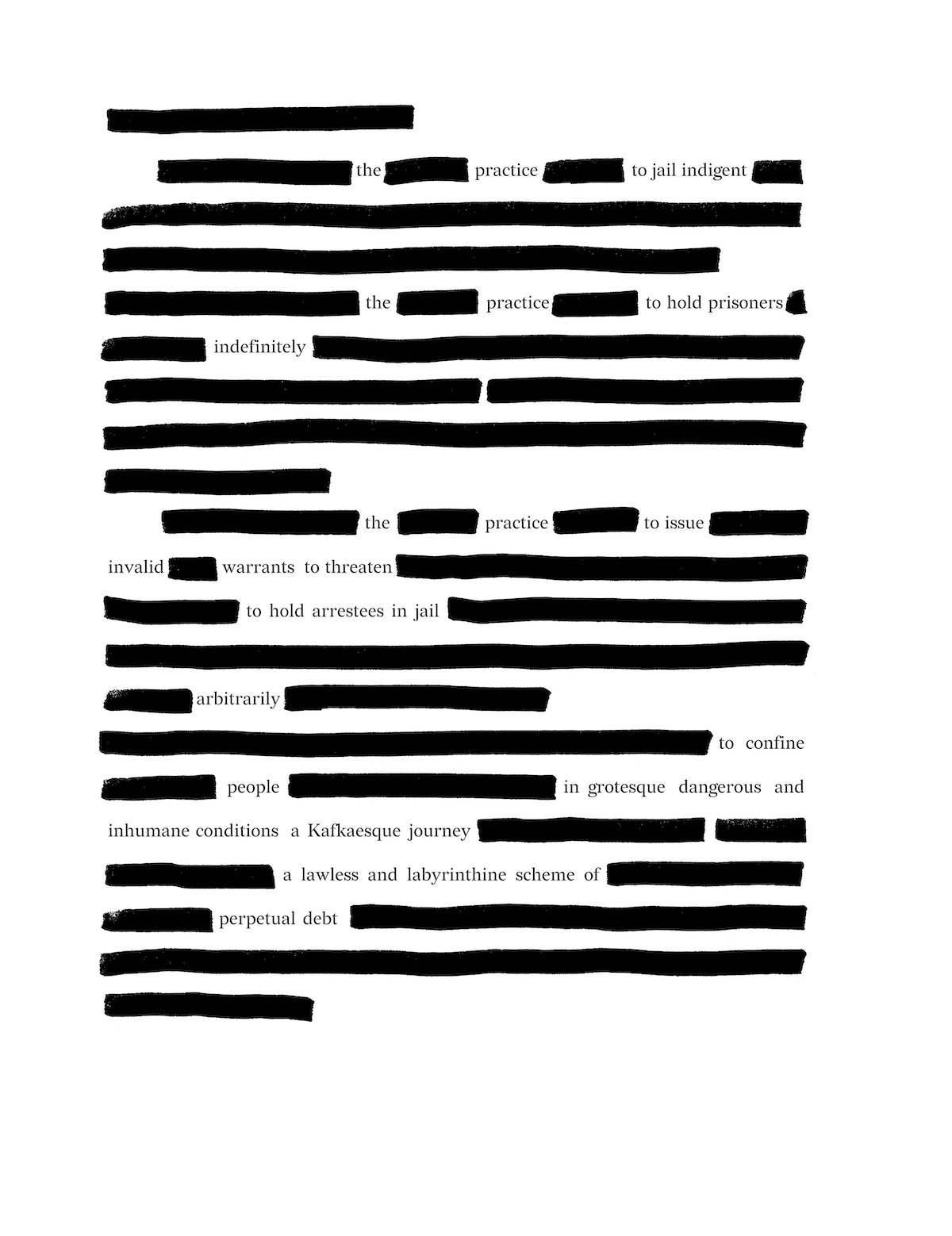

In your book, too, erasure becomes a powerful method of revealing loss and systemic racism. I’m particularly struck by your redaction of a class action complaint against the City of Ferguson.* When I read the following lines from your poem, “In Missouri,” they rise for me from the page in bas relief:

Can you talk about the work this kind of erasure is doing throughout Felon? Do you remember a point at which you decided that this was something you had to do?

RDB: I wanted to start with the cover. The way the word felon interacts with the artwork from the Jerome Project. Announcing how, on one level, the state’s use of prison and the public’s use of language erases the identities of people, reducing them, in a sense, to being understood only as absent.

It’s wild too, cause unless you’re really paying attention, you might end up thinking this book, this idea of incarceration, is rooted in the experience of black men. But it ain’t. See, I done did the thing society does: left Black women, Native Americans, white folks, Latinos, Asians, the entire spectrum of humanity that gets caged out of that cover, intentionally, not to double down on incarceration as an experience only significant to the lives of Black men, but to think about how the framing of the question as so is another form of erasure. That’s some meta shit though. And I don’t know if it comes across. But in a book that is deeply invested in the I, it’s important for me to recognize that the I is all those multitudes.

And so a poem like Missouri, in using redaction there, I am using it as a tool of revelation, and as a way to take a class action lawsuit that contains the multitudes of those harms, that as a form says this suit is representing these named folks and all the folks similarly situated, and say something in their voice about a particular fucked up part of incarceration. But I don’t know if there was a point where I felt that it was something I had to do, as much as it is all, the art, the poetry, a part of trying to be alive in the world.

AN: One of the things I’ve always noticed about your work is the degree to which it does reach out, the way it generates conversation with other writers and artists across and through time. In the “Publication Acknowledgments” portion of Felon, you talk about “having something of the desire of the quiltmaker.”

You’re just as likely to weave in lines by and shout-outs to musicians like Nas, Public Enemy, Tupac, and Springsteen as you are to reference films like Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, and other writers from Paul Laurence Dunbar and Etheridge Knight to contemporaries like Jericho Brown. And there are many more, of course, who we come to know only by their initials, or by names like “Fats,” “Juvie,” and “Star.”

In one of your “Essay on Reentry” poems, the one dedicated to the writer Nicholas Dawidoff, the speaker writes:

But we wear the mask that grins and lies.

Why pretend these words don’t seize our breath?

Prison, inmate, felon, convict.

You’re incorporating here words from Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask,” and in your acknowledgments you say the following: “I think Dunbar is the poet that made Dubois’s veil make sense for me—which is to say, Dubois, in my mind, has always alluded to Dunbar.”

What does it mean to you to have this kind of community (communal?) dialogue with other artists? Also, you’re making me think more about the ways in which the word, felon, embodies Du Bois’s idea of double consciousness, and also the many ways in which your book works on that word to expose/unveil/unmask, even deconstruct that reality.

RDB: As much as I am a poet, my reference point as a writer is Pete Rock and C.L. Smooth’s They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.), which flips a sample from Tom Scott and the California Dreamer’s “Today” into a legendary cut. I remember listening to Mos Def’s “New World Water” and hearing him say “cash rules everything around me.” That moment in time built a bridge between the Mos Def song and Wu-Tang. A kind of intertextuality happens when the artists do this. And this is what I’m after, ways to for my work to be invested in the past as well. I think the allusion that happens when I thread a Dunbar line into my poem is a kind of door to the Dunbar poem, a nod and an introduction to the community, so to speak. This is and has been integral to my writing, because it’s a way to worry over influence and acknowledge it.

To your latter point, and I think the two points are related, but the experiences of people we label felon does embody Du Bois’s veil. A bit different from Du Bois’s veil though, in a way, because we are not seduced into believing that we lack the markers of race in the way that we might be seduced into believing a criminal record no longer matters. But this question of the word felon and how it echoes Du Bois’s veil is also a reason for me to assert a different lineage, so that even as I wrote about incarceration, I can move with other currents of literature that remind me that this work is not provincial in that way.

AN: Do you see collaboration as an extension of this kind of intertextual discourse? Maybe “cross-textual” would be a better word? Could you talk about The Redaction, a project you have been working on with Titus Kaphar? Your work together was exhibited last year at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and features your poetry “in combination with Kaphar’s etched portraits of incarcerated individuals” [https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5056].

I note that the redacted legal documents in Felon are also set in a new font called Redaction, which strikes me as wonderfully subversive. You are literally redacting the documents with Redaction.

RDB: On some level, I would just say that Titus and I are out to create a body of work that is cohesive, that doesn’t rely on references to our other work to have value or meaning. Someone else might point out the various ways that it’s intertextual, but I know our first goal was to make sure we were creating art that stands on its own and isn’t dependent on the echoes of our practices.

When Titus and I went about thinking through the Redaction Project, it was all about finding ways to ensure that neither the visual art or the poetry was serving as a substrate for the other. And, in pursuing that, I think we were pursuing the creation of something that might be intertextual on a broad level but, you know, on a very specific level we were out to create a series of works on paper, a larger project, that had its own integrity. The ways in which it becomes intertextual were meant to be rooted in the way we referenced the mugshot, the legal documents — but not our past work.

There is always a tension between what we intend work to do and what it actually does. And so, I was pleased with your previous question — delighted really, because it affirmed for me that someone was seeing what I was doing. And wanted to thank you for it. We hope that readers pay our work that kind of close attention. But people don’t always see what you want them to see. And so if you plan this elaborate thing and no one sees it or notices it, is it actually an intertextual discourse? I hope it still is. I hope there is room for readers to invent the ways in which my poetry means and that the process of that inventions doesn’t preclude my poems from meaning in the way that I want them to be, which is very much as a thread in this giant thing we’re calling life.

AN: Since you mention the “tension between what we intend work to do and what it actually does,” I wonder if you might comment on the idea that writers shouldn’t veer from the lane or lanes of their own experience. I’m talking specifically about persona poems which attempt to embody the voice of the/an other, but in so doing, draw widespread criticism for appropriating that voice rather than speaking from it.

Does it ultimately depend on the dynamics of who is writing from what voice—and whether the assumed persona is working to destabilize traditional power structures as opposed to reinforcing them? Is the answer not to try because failing means further marginalizing that voice? And where does that, then, leave the imagination? How can we have meaningful conversation around this issue, especially when it involves matters of race?

RDB: A few minutes ago I finished reading Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country. A novel, the book does a lot of important historical and emotional work around how Black folks in America have historically confronted racism. It’s a good book. Kind of science fiction, but running right alongside this country’s history, using art to dramatize the lasting effects — and getting a good number of things in there, from lynching to redlining to the economic legacy of slavery. And it’s all done quite seamlessly. Oh yeah, Ruff is white.

When people do it right, we have no need to answer questions about what lanes folks should be in. The question, the way we deal with it, is always about how we castigate people for getting it wrong. Maybe that’s legit. But that doesn’t change the reality: get it right and you got it right.

The novelist has more practice with this. More experience believing the job is about seeing others. Maybe the poet, the contemporary poet, in a world of narrative first-person poems and lyric “I”s, believes that the voice always has to be them. But if that’s the case, the poet is robbed over their superpower: their ability to notice and distill a world — not their ability to notice and distill their world. Such a selfish move, I think, it would be if poets believed that every “I” needed to be them. And frankly, I don’t even think of it as persona. For me, persona is when you are naming and acknowledging and making it clear that the voice is specific, locatable, as opposed to just a speaker that isn’t named, one that becomes, if the writer does it right, the reader, every reader, each time they utter the word, “I.” while they read your work.

So I guess I’m saying write what you want, all of it, and be whoever you want to be on the page, because otherwise what art might do is constrained. And that would be sad.

AN: What are you working on now?

RDB: Turning Felon into a solo show. There is this notion that poetry books have a narrative that can be tracked by a reader. Sometimes that’s true, but sometimes it’s not. And Felon lacks that narrative. But I wanted to create one with some of the poems. So I’ve developed a script and am slowing going through the process of learning the pieces by heart, the pieces that will be in the show. And I’m looking forward to bringing the piece to the stage.

AN: Ok, I promised the last question would be my last, but I can’t help it: where do you plan on performing the solo show and what’s the projected timeline? I realize that may be an impossible question to answer in the middle of a pandemic.

RDB: Planning on where to perform a solo show is so challenging. New Haven has an amazing drama scene, so I’d love to perform at the Yale Rep. And more broadly, I want to tour it. New York, DC, San Francisco. Within prisons across the country. Honestly, this started out as a challenge to myself, a way to control how a narrative might unfold within a poetry collection. Now, it’s become a way for me to have belief that the world will, at some point, invite the kind of intimacy that theater demands. So I’m preparing for that tomorrow.

*Felon notes that “In Missouri” is one of four poems in the book “redacted from legal documents that [Civil Rights Corps] filed to challenge the incarceration of people because they could not afford to pay bail.”

THREE POEMS FROM FELON

Republished with permission from W.W. Norton & Company

Blood History

The things that abandon you get remembered different.

As precise as the English language can be, with words

like penultimate and perseverate, there is not an exact

combination of sounds that describe only that leaving.

Once, drinking and smoking with buddies, a friend asked

If I’d longed for a father. Had he said wanted,

I would have dismissed him in the way that youngins

dismiss it all: a shrug, sarcasm, a sharp jab to the stomach,

laughter. But he said longing. & in a different place, I might

have wept. Said, once, my father lived with us & then he

didn’t and it fucked me up so bad I didn’t think about

his leaving until I held my own son in my arms & only

now speak on it. A man who drank whisky like water

once told me & some friends that there is no word for

father where he comes from, not like we know it:

There the word father is the same as the word for listen.

The blunts we passed around let us abandon our tongues.

Not that much though. But what if the old head knew

something? & if you have no father, you can’t hear straight.

Years later, another friend wondered why I didn’t name

my son after my father, as if he ain’t know, Some things

turn your life into a prayer that the Gods will certainly answer.

Essay on Reentry

for Nicholas Dawidoff

Of prison, no one tells you the time

will steal your memories – until there’s

nothing left but strip searches, the hole,

the fights, & hidden shanks, the spades games.

You come home & become a parade

of confessions that leave you drowning,

lost recounting the disappeared years.

You say fuck this world where background checks,

like your fingerprints, announce the crime.

Where so much of who you are betrays

guilt older than you: your pops, uncles,

a brother, two cousins, & enough

childhood friends for a game of throwback–

all learned absurdity from shackles.

But we wear the mask that grins and lies.

Why pretend these words don’t seize our breath?

Prisoner, inmate, felon, convict.

Nothing can be denied. Not the gun

that delivered you to that place where

you witnessed the images that you won’t

let go: Catfish learning to subtract,

his eyes was a heroin-slurred mess;

Blue-Black doing backflips in state boots;

the D.C. kid that killed his cellmate.

Jesus. Barely older than you, he

had on one of the white undershirts

made by other men in prison, socks

that slouched, the shackles gripping his shins,

boxers. Damn near naked. Life waiting.

Outside your cell, you could see them wheel

the dead man down the way. The pistol

you pressed against a stranger’s temple

gave you that early morning. And now,

boxes checked have become your North Star,

fillip, catalyst to despair. Death

by prison stretch. Tell me. What name for

this thing that haunts, this thing we become.

Photo cred: Gioncarlo Valentine

Reginald Dwayne Betts is the author of four books. His latest collection of poetry, Felon, was published in October 2019 by W.W. Norton. He has been a Guggenheim Fellow, an Emerson Fellow at New America, and a Fellow at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies. He holds a J.D. from Yale Law School.