Remedios: Tommy Archuleta in Conversation with Amy Beeder (and five poems)

Remedio: Añil del Muerto

To aid safe passage, pick the blue-green leaves when the flowers

have fully bloomed. Air for one day and one night prior to

mashing. Coat the tip of a wooden stake with the pulp before

driving it into the foot of the loved one’s grave. Bury the rest of the

pulp at the base of the headstone. Pray ceaselessly as before.

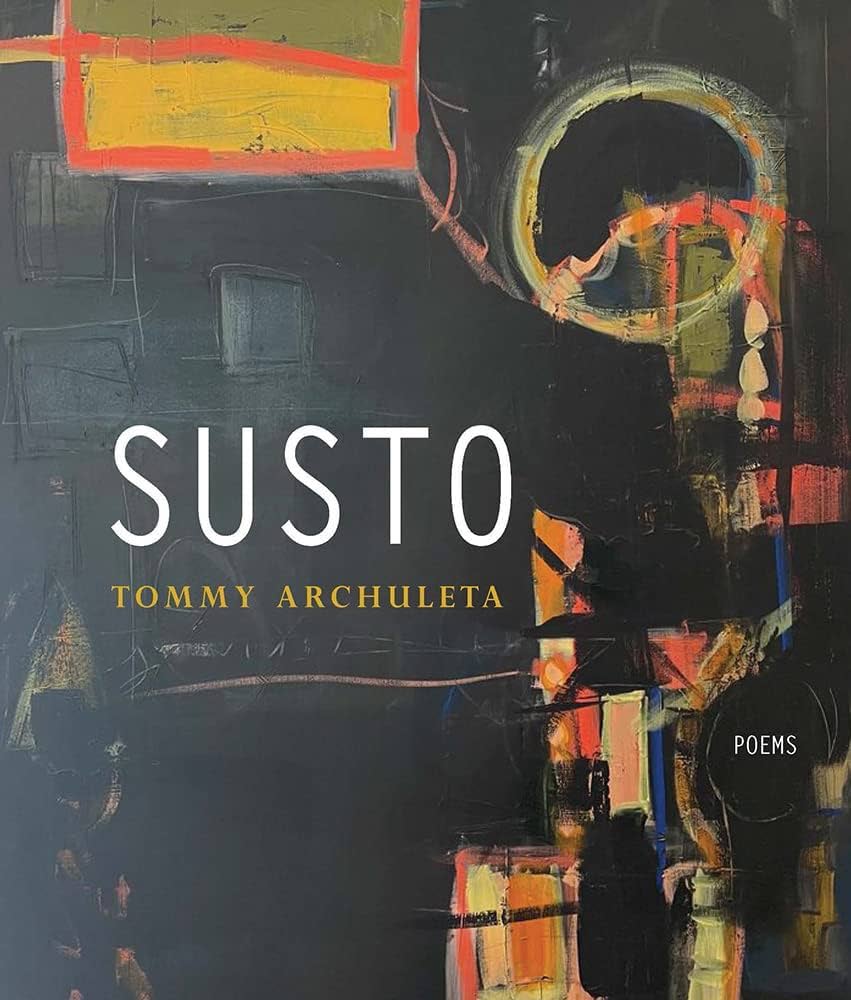

These Spanish folk remedies appear throughout Tommy Archuleta’s haunting, incantatory debut collection Susto. In his words, they serve as “mojóns, or cairns” that “amount to the blood and bones” of the work. I had the privilege of speaking with Tommy about his book―as well as dreams, form-as-mosaic, New Mexico wildfires, his job as a mental health and substance abuse counselor, why St Raphael is the darkest angel, and so much more. The poems that follow our conversation are from Oneiromancy: A Pocket Dictionary, a manuscript in progress.

AB: There are several things that excited me right away about Susto: the setting and the subject first, then the form, and finally the voice, which seems both prophetic and appealingly human: Dana Levin has called it “oracular…yet bemused.” First, though, for readers yet unfamiliar, would you speak a little about the title and your impetus for this book?

TA: I wrote very little between 2010 and 2014. I left the MFA program at UNM spring of 2010 because I had little interest in studying Proust, Hopkins, nor did I possess the wherewithal to teach English 101 to undergrad business majors. This may well secure me a seat in literary hell. Anyway, in the summer of 2010, I took a job working as a medical technician in a drug and alcohol inpatient facility in Santa Fe and, after work, I’d rework the short germs now and then that surfaced while participating in Lisa Chavez’s poetry workshop.

Then, my mother dies of congestive heart failure August 17, 2013, which totally kneecaps me. The waves of grief for months afterward would send me to my knees every time. Food tasted funny after she died. Sometimes I’d sleep for over 12 hours, other times I’d go without sleep for two or three days. Bobby Bly felt strongly that grief and loss can provide a doorway for some men to a world of emotions they hadn’t at all know about. Mom’s passing did just that for me.

As such, I wouldn’t revisit MFA germs until January 2014, when I enrolled in the masters-level professional counseling program at New Mexico Highlands University. I’d rise at 4:30am Sunday through Saturday, write for three hours and then head into the day. I’ve pretty much stuck to this ritual since then. By spring of 2016 roughly forty or so short lyrics had amassed, all of them direct descendants of the aforementioned germs. I prayed for a title for the collection that was forming, but none came. Then, in the spring of 2017, I took a required course on the 5th edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual published by the American Psychiatric Association. Prior editions weren’t much interested in culture-based conditions—not so with the 5th. Meaning, at the tail-end of this massive volume, page 836 in fact, I found this:

Susto (“fright”) […] is an illness attributed to a frightening event

that causes the soul to leave the body and results in unhappiness

and sickness, as well as difficulties functioning in key social roles.

AB: It’s a wonderful title, and it’s interesting that you mention Bly’s theories about men and emotion. That kind of struggle did resonate throughout your book; in fact, it seems to me that images of return in Susto often represent a kind of waking of the spirit, a coming to terms with grief and loss, like the homecoming in “A stone a leaf a stash of cranes:’

Soon you will know

every window back home

once nailed shut now

opens and closes freely

That every saint you snapped

in two now stands

whole on the sill

I found those themes as well in a short essay you recently shared about your job as a mental health and substance abuse counselor for the New Mexico Corrections Department. Would you speak a bit about ways that being a counselor intersects with or informs your work as a writer?

TA: My being a mental health counselor has much to do with my being a person in recovery who has enjoyed twenty-four years plus of continuous sobriety from alcohol and all illicit drugs. And the sobriety piece, especially in the early going, had much to do with obtaining my first library card from the Santa Fe Public Library. Honestly, I never ventured far from the poetry stacks, where I found Gary Soto. Soto led me to Sherman Alexi. Alexi led me to Whitman, and Whitman led me to the Salvation Army Thrift Store where I found a Royal typewriter for twenty-five dollars. That typewriter cranked out my first published poem in the Manzanita Quarterly (R.I.P.), Spring 2004.August 2004, I entered the College of Santa Fe (R.I.P.) as a full-time traditional student, thereby commencing my second cathartic, spiritual experience next to getting sober: Dana Levin’s poetry workshop.

Now, that’s a long-winded way of saying, I don’t know.

What I do know:

I know that my favorite toys as a child were the mini-memo books my maternal grandfather often gave to me that came with their own matching mini-pens.

I know those pens loved to write in blue ink only.

I know I’d spend much time writing whatever word came to mind sans caring if the order made sense or not.

I know I stopped writing when I found the cure for adolescence: Johnny Walker Black.

I know I came this close to dying an alcoholic death (yes I really was that bad).

I know that journaling those first few years of sobriety rekindled my love for writing.

I know that for some of us recovery folks, writing equals Higher Power.

I know that not all wounds are meant to heal.

I know that I’m a wounded healer working steadily toward healed-healer-dom.

I know that I’m an un-convicted felon that offers mental health support to convicted ones.

I know that I love my counseling post at the state pen.

I know that I love my father, whom I refuse to bury while he’s still alive.

I know a strong correlation lives between Creator, Creation, Creating, and Creations.

I know that if it weren’t for doubt I wouldn’t know what faith looks, tastes, or feels like.

AB: Here’s the beginning of “C[andling],” a poem that appears in this issue:

Word arrives:

The fire’s miles wide head will make the outskirts of town by morning

I’m dared to burn these dead palm leaves

Believe says father and the wind will die down

and from another, “Bonfire”

All this snow black as the holy dark

The rose window opened only some

No way can you see the altar from here I know I know

But it’s there alright

Somewhere inside the bonfire

One of the things I admire about your work is the presence of landscape, and particularly what I feel is an effortless intimacy, in contrast to how Northern New Mexico seems often to function as exotic or affected foregrounding. Can you speak a little about how you see place in your work? I’m particularly interested in thoughts about the wildfires―always a part of this place, but now more so.

TA: Where Susto is concerned, its development, and so forth—the eastern slope of the Jemez Mountains, the Black Canyon, Cerro Pelon, and the valley landscape of the Cochiti Reservation—all of these could be viewed as main characters in this work.

Parents, even, of the many roots and plants who also star in the book.

In this way, the Cochiti valley and surrounding mountains and hills are extensions of that other mother present, but not rendered per se, concretely: mother earth.

Another mostly cloaked character of Susto: the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, namely the genocide, slavery and other atrocities inflicted on the Cochiti people at the hands of my forefathers. I fear I have yet to forgive them. Perhaps some day I shall. Perhaps Susto is something like a sole step taken in that direction—I don’t know….

∞

Years ago, I fell in love with the way Wendell Berry is in love with William Carlos Williams.

It’s as if the latter validates still the former’s more lyrical self as a “poet of place.”

One had the means to live anywhere else but home, but no. The other, same.

So we have place as geographic locale. Ok.

Lately, though, place as emotional state has been ringing my bell[s].

How about place as psychic state and/or spiritual place? O yes, most definitely.

Example: b/c I do all I can to write for two hours every morning, save grave illness, I write the morning after the night pop falls, again.

I write the morning I receive word from the prison that yet another inmate in “supermax” commits suicide while I lay sleeping.

I write the morning the woman I love texts me that her father’s cancer has returned.

I write the morning the Sandoval Fire Department calls and says volunteer evacuation of the Cochiti Reservation is now in effect.

And let’s not forget place as point along any one of the impossible stages known as the human

lifespan.

You wanna know what I think?

I think Williams and Berry surrendered to Poetry at such a depth that Poetry had no choice but to teach each of them how to “see. ”

Speaking of fire…

∞

I could’ve grown up to be a convicted arsonist, easy.

The “place” of the first fire I built: the living-room of our home on San Jose Avenue, age 9.

I recall vividly mom scolding me for “stealing” matchbooks at restaurants and motels.

This pattern was tied to another: threatening me with Hellfire if I didn’t stop “playing” with them.

My 9 year old response: I wonder if Hell has PopTarts and Sugar Pops and Orange NeHi Soda…?

In fact, these very memories came reeling when pop and mom and I voluntarily evacuated our Cochiti home when the Las Conchas fire of 2011 came within 10 miles of us.

And again they arose when pop and I evacuated last year when the Cerro Pelon fire came within

5 miles of our home.

Anyways, living here teaches you how to talk to fires of all types and sizes.

How to pray to them.

Thank them now and then for what they give you, take from you, and for what they leave for us

to find after they die.

Lean into suffering. Befriend it.

These sentiments of Thich Naht Hanh…

I think Poetry teaches us to do these things.

I also think She demands from us way, way too much.

AB: One review called this a book of “untitled poems.” When I first read it, I thought of each first line as the title, but I could absolutely see the book as one long poem as well. How do you think it, overall, in terms of form? And does it matter?

TA: As the Muse slowly kept sending me short lyric after short lyric, subsequent draft after subsequent draft, I began to experience this work as mosaic. This view strengthened when the work began prompting me to start arranging the “tiles.” Honestly, the present order of the tiles and remedios wasn’t arrived at until the second to last draft of the manuscript. And, so, because the work spoke to me as mosaic in the early going, I view this work as a book-length poem today and always.

Now, does my view of the book’s form matter? I’ll say, no. Let me also say that what matters most to me is that those who lend their attention to this work find within its pages an understanding friend or two, or three or four, et cetera.

AB: Why is St Raphael the darkest angel of all?

TA: Of the seven “fallen” archangels, antiquity has Raphael as the only one gifted with the power to heal, thereby making him a “wounded healer.” And healers, as is well known, must be willing to go to places sometimes void of light.

It’s funny, but most trauma survivors that I know personally, and those that I have treated, report that the emotional, psychological, and physical forms of pain teach one how to dance with the Dark.

As mental health counselor and substance abuse counselor for the New Mexico Corrections Department, the past four and a half years have introduced me to forms of darkness Hollywood has yet to render, and likely never will. At the same time, my clients, especially those assigned to segregated housing, aka “supermax,” continue to heal parts of me I had no idea were ill and failing.

AB: Were the poems in Susto originally written in this sequence? (If not, what were some of the first or last poems?) Are there ways in which certain poems opened up the collection, shaped it, or completed it for you?

TA: I love how deeply your questions cut. They hit bone, they do!

It’s like you’re the poetry detective questioning me, your unshaven, unkept, hellhound suspect.

Fact: the only sequential thing I can be accused of is that of living year after impossible year since birth—that first complicated traumatic event we all must survive—and barely, so!

When I started to write again after mom’s passing, sometimes a line or three would surface. Mind you, I wouldn’t wake with any sense that I should start writing again, or that it might be a good idea

for me to do so. I had no say-so in the matter, looking back:

You healers born mute—

which root

first seized you

Other times, the thing would work itself up from my guts to my throat in the form of a metered rhythm. I part blame thirty-plus years of drumming for this. Part blame her highness, The Muse:

__ /__ __ /

/ /

__ / /

Other times, I’d skim the little pages of the mini-composition notebooks I loved so much during my MFA days at UNM. I’d scribble down religiously the “germs” that would come flying out of the mouths of my workshop comrades, to include my captains, Chavez and Levin.

As the day mom died fell further and further back in the calendar, each dawn got in the habit of sending me what I then called, and still call, tiles. Tiles that might someday offer up a mosaic of sorts, depicting….

Well, depicting, at that time, what I called I haven’t the fucking slightest

∞

Years before Billy Stafford left for good, he gave us all a poem bearing a first stanza that describes, handily, not only my Susto experience, but also how poetry happens, to at least some of us:

Your exact errors make a music

that nobody hears.

Your straying feet find the great dance,

walking alone.

And you live on a world where stumbling

always leads home.

Mistakes, wrong turns, formal and/or informal vows to abort, public and/or private manuscript burnings, swearing never to write again, post-rejection slip ice cream binges—all these factors and scores more were part and parcel of the massive heap of rough stone I quarried, a.k.a., the first draft. As crucial to Susto’s unfurling were the trusted sherpa services of one Dana Levin, whom I showed the first draft to circa summer 2016 at The Tea House, Canyon Road, Santa Fe, NM, USA.

Dana: Ok, here’s what I have to say about this (fingers lightly drumming the table): Keep going.

Me: Really, keep going…?

Dana: Yes–no matter what, keep going. Listen, trust what you’ve been given so far. Trust the work itself. It’ll guide you if you allow it to.

Me: But, but…I don’t know where this is going, where it’s taking me.

Dana: You don’t need to know. You just have to keep writing. Also, it’s ok to not know.

I’m convinced that a great many of us thirst for permission to continue our craft. Perhaps this is one reason why the heart and earth’s core swap locations when yet another rejection email arrives in one’s inbox. Flash-forward a dozen or so drafts, and there it is, in a box stored away in a dark corner of the garage: mom’s cherished books on curanderismo. Just handling them filled me with the strong sense that now a few, maybe more, remedios need to be added. As such, these were the last tiles to surface.

∞

Fact: I still have no idea what the Susto mosaic depicts.

Fact: I’m still learning how to dance with not knowing, a.k.a., Darkness.

Fact: I touched a frog once. It was spring. Nighttime. I must have been twelve or so.

AB: I understand that the five poems in this issue of Plume are part of a new book. Would you mind speaking a bit about your next project?

The only thing my ex-wife left behind, fall of 2019, was a copy of Rose Inserra’s Dictionary of Dreams. Which I may or may not return. We’ll see. Who isn’t drawn to dreams? Plainly, C. J. Jung was drawn to them, and so it’s his insanely exhaustive take on dreams that I hold dear.

And because he’s dead, I’m guessing he won’t mind too much if I simplify here his take:

- they tell us where we’ve been

- they tell us where we are

- and they tell us what our future might hold

And because I too am drawn to dreams.

And because I work with the dreams of my clients as a mental health therapist.

And because, too, of the long, shimmering presence of dreams throughout Poetry’s history.

I suppose for these reasons a voice decided to up and surface one day during the tail-end of the covid shutdown.

A voice I for one had never heard before.

One steeped in the waking life waters of smart-assery.

One darkly humorous, too, at times, which couldn’t be more unsurprising, I suppose—given the overarching theme of dreamwork.

Perhaps, too, Oneiromancy: A Pocket Dictionary, a chappy through and through, is an attempt to follow the example of my sherpa’s sherpa, one Louise Glück (second namedrop bomb, sorry and not sorry).

An example that says, essentially, among scores of other things:

Learn how to give yourself permission to continue, and soon you might find the wherewithal to reinvent yourself on the page.

Oneiromancy: A Pocket Dictionary

Dreams: they are the facts from which we must proceed.

C.G. Jung

A[rchitect]

I catch you staring at the moon

Which is to say never is anyone truly alone

And the more I stare at you the more the moon darkens

Not true I never said night resembles the last hour of life

Love and loss are tricks of light played on us by the Architect says father

If by Architect he means From dust to dust then so be it

Now the moon is writing a poem

It’s about some poet most poets have never heard of

Manhandling fire and smoke one moment

Shadowdancing with a torn page from the Inferno the next

What gets me is the Face it—love is just another word for loss reference

So I keep on staring

Now you’re leading our horses to water

The herd still hours away from settling

B [onfire]

I vote we keep The earth as swallow as

Finch as trowel as a floating

Starstrewn gown minus Mary

The cellist drops a full octave

The notes land splash and fastlike

O you brought May Loss & Afterglow Never Touch my favorite

Doesn’t the robed figure look awfully familiar though

Another octave goes bye bye

And what’s all this about collecting bad children in long wooden carts

All this snow black as the holy dark

The rose window opened only some

No way can you see the altar from here I know I know

But it’s there alright

Somewhere inside the bonfire

C [andling]

Word arrives:

The fire’s nine milewide head will make the outskirts of town by morning

How dare you dare me to burn these dead palm leaves

Believe says father and the wind will die down

I google instead the distance from navel to lung

Lung to tongue

Tongue to Nova Scotia

Father: So much for the control burn that was your loving mother

A stand of elms motions to RIP the valley’s finest horses

Seconded by the Pope who hasn’t eaten in weeks

Maybe war wouldn’t exist if all countries like Vanda orchids

had aerial root systems

Maybe the burn scars of years past will heal us

Preferably with something post-Jungian to say

*Candling: a single tree or small stand of trees burning from the ground up.

–U.S. Forest Service

H [ope]

I’m heading south in the pitch dark the fog just lifting

Something falls somewhere behind me

I strain to say your name but it comes out as Careful where you step

Like clockwork praying is out

There is one hope though (maybe

That’s what fell just seconds ago): earthworms

Boy do they know how to party

It’ll be firstlight soon one says to the other

All this talk of communing by taste over touch

At this age what hurts today won’t hurt tomorrow

O look weeping softly in the azalea bushes an AK-12

The fifth generation of Kalashnikov rifles

Right where the young soldier threw it

W [omb]

Finally the others have drifted off to sleep save one

The pull to leave and search for something

Anything numb for now

A white dove lands nearby

No it’s a crow

White as the robes she wore when I last saw her

It’s not the wavering hum so much

It’s all the warm darkness what’s left of my heart wants back

Wants it like anything alive craves water

And more than overexposure to florescent lighting

More even than never returning

I fear giving in to the cold don’t you

The cold encasing what some call despair I call discipline

Tommy Archuleta is a native northern New Mexican. He works as a mental health therapist for the New Mexico Corrections Department. Most recently his work has appeared in the New England Review, Laurel Review, Lily Poetry Review, The Cortland Review, Guesthouse, and the Poem-a-Day series sponsored by the Academy of American Poets. Susto, his full-length debut collection of poems, published by the Center for Literary Publishing, is a 2023 Mountain/West Poetry Series title. He is also the author of the chapbook, Fieldnotes (Lily Poetry Review & Books, 2023). He lives and writes on the Cochiti Reservation.