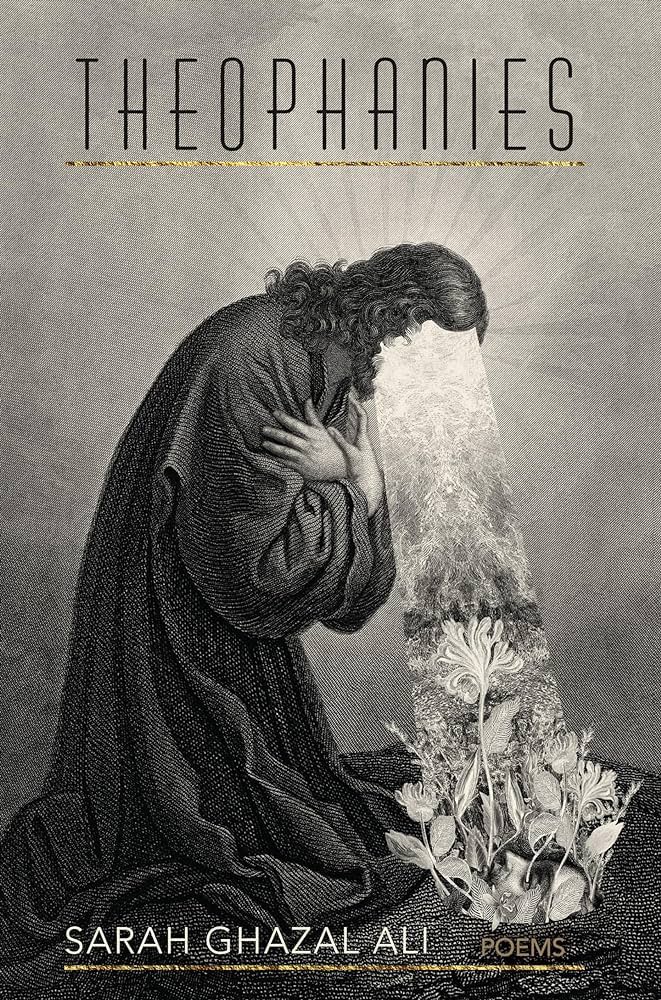

review of Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali. Alice James Books.

by Jane Zwart

Sarah Ghazal Ali.

Alice James Books

$18.95 trade paper (100p)

ISBN 978-1-949944-58-7

All of us who read poetry, I suspect, have stanzas to which we return for reassurance, stanzas that lend our hopes backbone or our griefs consolation. I’d also be willing to bet that all of us poetry readers have writers we gravitate toward not so much for reassurance as for the assurance we hear in their voices: an ease in their telling of things, a command in the way they wield language.

And it is not that Sarah Ghazal Ali’s debut, Theophanies, is short on compassion or craft—on the contrary, it is long on both. I will not go back to her poems, however, for my own reassurance or for her assured voice. Instead, I will go back to them because of their unsettling ambivalence. I would not say, even, that these poems tender comfort—at least not inasmuch as comfort would let us make peace with the news of Nabra Hassanen’s sexual assault and murder, on the one hand, or, on the other, permit us to judge Mary Magdalene, who declares “I am my only / witness.” Nor do the poems in this book impart certainty, enshrining a single approach to the Qu’ran or the Bible or “The Story of the Cranes.” Even the seemingly personal poems in this collection hedge, their portraits coming with facets (“Daughter Triptych”) and their stories in time-stamped installments (“Motherhood 1999”). That said, the discomfort Theophanies stirs up is tender, and the doubts it confesses are wise.

And these poems are tender and wise, first and foremost, by virtue of their flickering. In fact, the theophanies that the book’s title promises are holograms, shifting between visions of the divine and figments of the speaker’s imagination. Take the poem “Annunciation.” Its title leads us to expect a poem focused on the annunciation that Renaissance paintings typically depict: Gabriel’s telling the virgin Mary that she would bear the Messiah. But in Ali’s poem. Sarai—the patriarch Abraham’s long-barren wife—shows up in Mary’s stead. The poem begins

My pillaged body

is not as interesting

as my virginal sister’s.

So Sarai, simply through her role as the poem’s speaker, unseats Mary in this “Annunciation.” But then the poem’s flickering begins: Sarai summons the more “interesting” Mary back, standing behind her, almost out of view. The older woman, admittedly, soon usurps the spotlight again before allowing Hajar, her maidservant, to make a flash cameo. And in these repeated substitutions (of Sarai for Mary and Mary for Sarai and Hajar for Sarai), we see in microcosm Theophanies’s tendency to swap the figures and images before us, to court uncertainty.

However, the uncertainty that Ali’s poetry courts—thanks to its figures taking turns shifting in and out of view—is a subset of wisdom. Specifically, “Annunciation” contains the two-sided wisdom that while difference matters (a “pillaged body” is not a “virginal” body), difference does not forbid connection (Sarai claims, looking past centuries and potential jealousies, Mary as her sister).

But there is even more canny ambivalence built into this poem—and into Ali’s collection as a whole. Later in “Annunciation,” Sarai insists,

They visited me first,

you know. God

& two angels came

with glad tidings,

announced I would flower

with a boy. But

all you remember

is what came next—

I hung my head & laughed.

Here, too, Sarai nods futureward, toward Mary, even as the reader has to peer in the opposite direction: backward, past the expected subject of the annunciation—the virgin mother—to the barren mother in a more remote past. What’s more, Sarai needles her listener, the “you,” for not looking back far enough, for missing the way that the eruption of the divine into the mundane recurs. She chastises us first with the remark “They visited me first, / you know.” But even once we get closer to this earlier visitation, we stop short, according to Sarai. “All you remember,” she accuses, “is what came next”: her incredulous laughter on hearing that she “would flower / with a boy.” This poem’s speaker, then, is not just the recipient of annunciation; Sarai is also a messenger. That is, she assumes the angels’ place, visiting us in annunciation, making us the subjects of an unsought revelation. And, in so doing, she makes us her subject. More: she makes us subject to theophany.

The poem “Matrilineage [Parthenogenesis]” furthers this claim of connection and recurrence. Adopting the form of a family tree but making light of biological constraints, this poem grafts women from the Qu’ran—Hajar, the maid whom Sarai sent to Abraham’s bed; Asiya, the Pharoah’s daughter who raised the Israelite Musa as her son; Maryam, the mother of Jesus; Khadijah, the prophet Muhammad’s wife—into “a mother line” around “an i inherited.” The wisdom here, once again, hinges on ambivalence, for the lines in this diagram signify both distance and proximity; they, like “Annunciation,” preserve dissimilarities but also characterize these women as kin.

Along with the ambivalence in “Matrilineage [Parthogenesis],” though, it is tenderness that shapes this poem, which invokes the order and breaks the rules of family trees. What but tenderness, after all, would bend the laws of genetics to make rivals sisters? What but tenderness would sideline the laws of ancestry in order to position the prophet’s wife as the offspring of his mother and foster mother? It is tenderness, as well, that we see in this volume’s opening poem, where Ali writes,

My faith gets grime under its nails,

unburies maybe-mothers

to suckle them sacred.

“Matrilineage [Parthenogenesis]” enacts exactly this work. Too wise to be certain of itself, this poem furthers the ambivalence at play in Theophanies with its diagram of “maybe-mothers.” And too tender to leave them in the ground, the poem also “unburies” these women and “suckle[s] them sacred.” The speaker, then, swaps the roles of mother and child, and she treats corpses as one would newborns. That is, she answers binaries and their mutual exclusions with flickering reversals, at once scandalous and reverent. She unsettles what we think we know in order to make us reliant on the heart that clenches over graves and cradles. No wonder the words “womb” and “tomb” prove interchangeable throughout Theophanies.

So when the poem “Fatal Music” declares, “I love most that object which evokes another,” you wouldn’t be wrong to hear that as a declaration this debut volume makes. Theophanies, taken whole, does love the reach and flicker of evocation. It loves word play and metaphor. It loves stories that evoke other stories, lives that evoke other lives. And it loves “the mirror [that] window[s],” evoking, from the speaker’s reflection, the “refract[ion of] others, foremothers.” Of course, what becomes clear as one reads Theophanies is that love is not just Sarah Ghazal Ali’s response to these evocations; it is also their source.