The Voice of the Dragon

A Conversation with Katy Didden

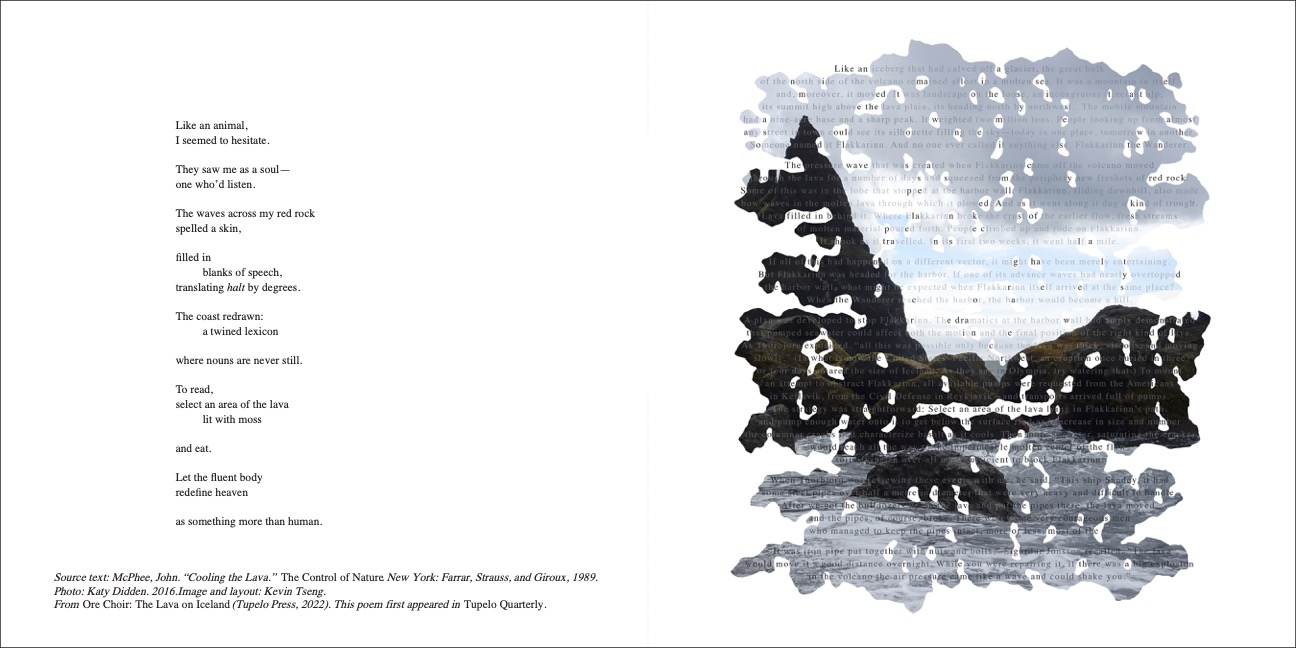

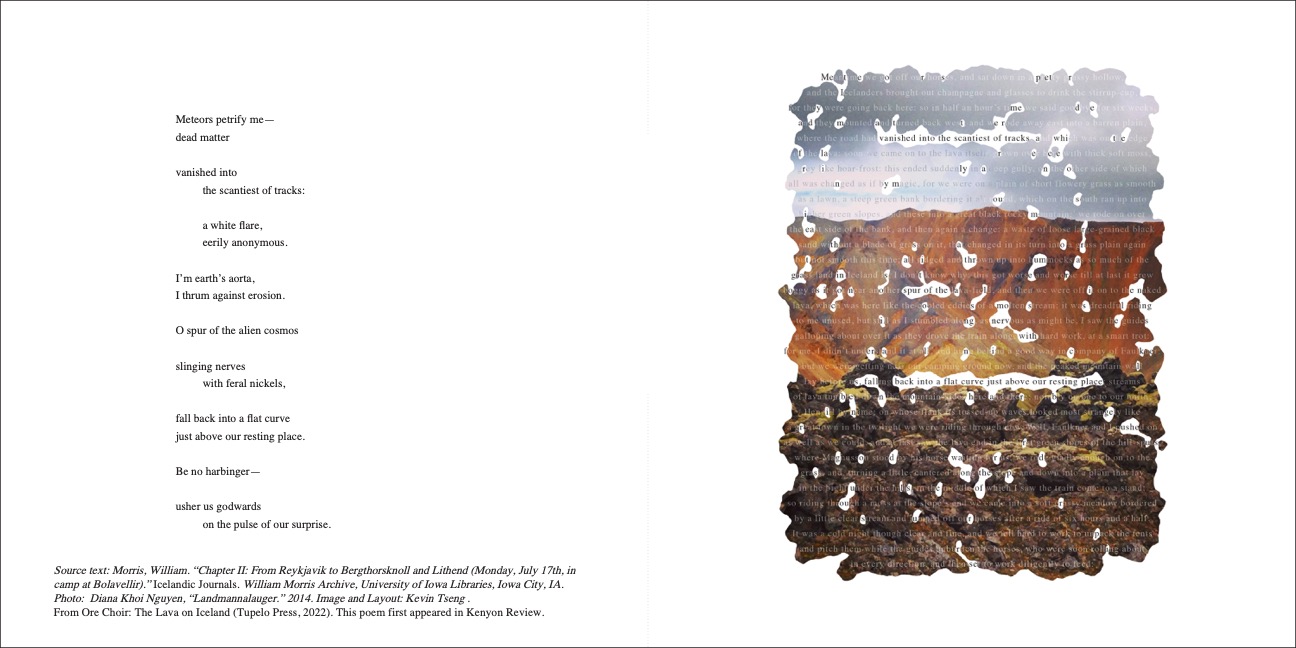

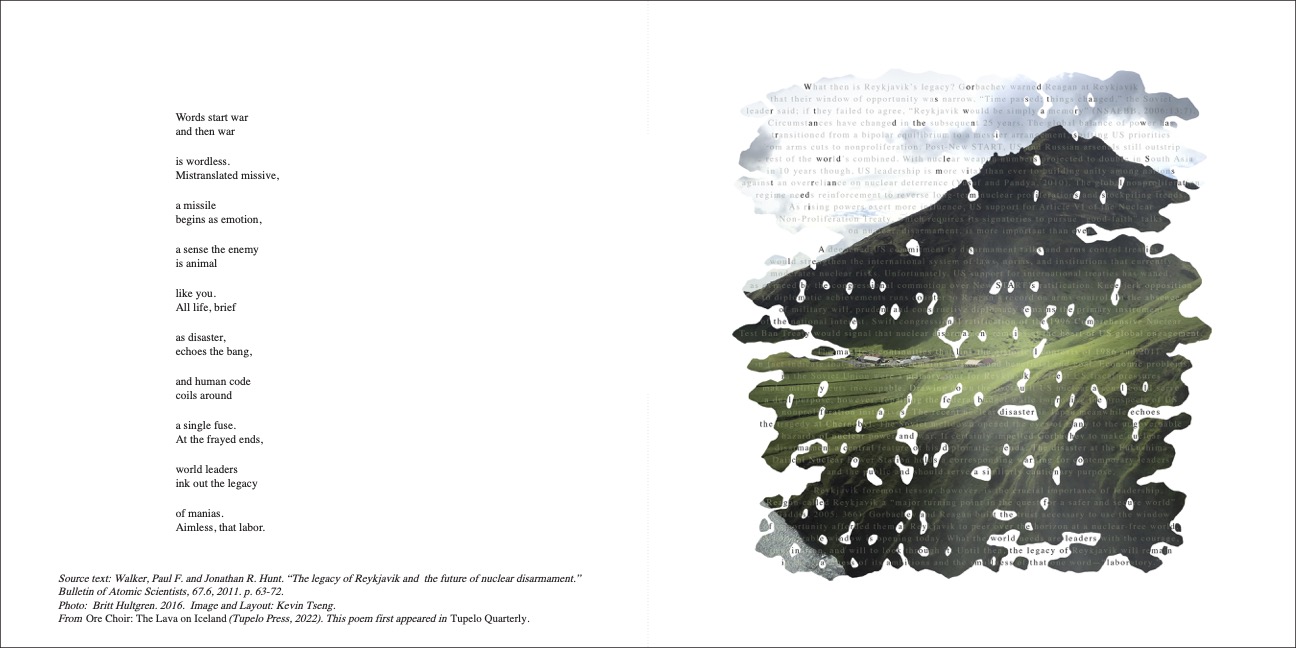

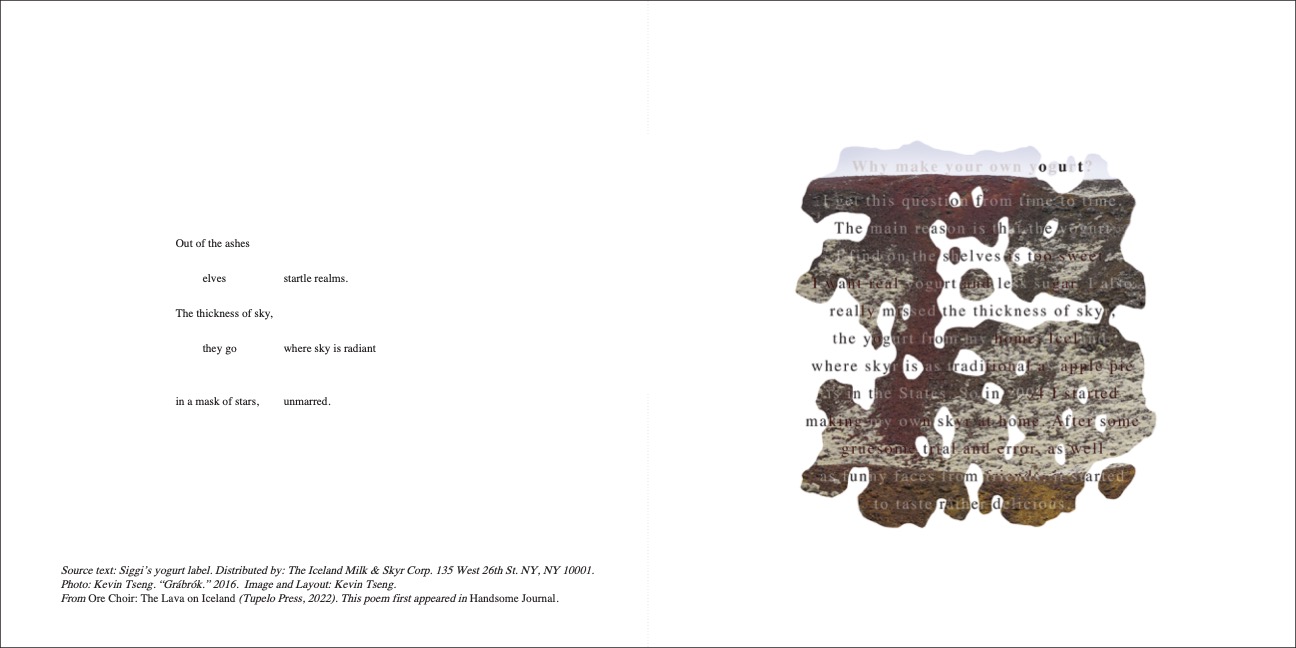

Katy Didden’s new collection, Ore Choir, is a book to savor on many levels. It is at once a collection of lyric voice poems that are also erasures; a hybrid book that includes a composite for each poem of the source text used for the erasure overlayed with a landscape of Iceland. Finally, there is a section of scholarly facts and notes in the back that would satisfy the needs of researchers who want to know more about Iceland, volcanoes, and Norse myths that provide a backbone for some of these poems. But the determining factor around which all other elements of Ore Choir coalesce is the voice: singular, oracular, unsparing, wise, speaking from deep time to our time, a voice that sounds a warning. The voice of lava, the voice of the dragon.

Katy Didden and I met in 2015 as fellows at MacDowell where we had a chance to read each other’s work. At that time I read a couple of the erasures that appear in Ore Choir. Seven years later, we spoke again in early 2023 about all of the above and more.

FR: I love your new book, Ore Choir! And I re-read your first book, The Glacier’s Wake. The two books seem related.

KD: Thank you!

FR: So, Iceland. It seems to be more than a country in Ore Choir. It seems to be a living, breathing being. Is that what you intended?

KD: Yes. I just listened to this really cool lecture by an art historian from Iceland, Æsa Sigurjónsdóttir. She introduced the concept of “Icelandicity,” which is studying how the country of Iceland figures into the global imagination and how people project onto it symbolic or mythical resonance. She discussed this in terms of Icelandic artists, looking at the extent to which they play into or against what she’s calling this Icelandicity. When I heard that term, it seemed like a useful vocabulary for talking about Ore Choir. I’m also investigating why it is that Iceland appeals to artists and writers around the world. It could be that I’m just an example of what she’s calling “Icelandicity”! But I hope I’m also participating in trying to understand it. I’m interested in how Iceland has a global impact that’s cultural but also physical—what happens to the world when volcanoes erupt? Of course, that happens in any volcanic country, but for this project I was looking at Iceland because it has unique volcanic characteristics, and it’s a place where you can walk beside a divergent plate boundary (the Mid-Atlantic Ridge runs through Iceland, separating the North American and Eurasian plates). I’m drawn to this volcanism because I’m interested in what it means for the earth.

FR: I’ve heard that it’s kind of a mystical place, and otherworldly things happen there.

KD: Yes, I think that could be true. I don’t want to over-romanticize it, but to me, maybe the answer is the geology of Iceland, the relative youngness of the land, and that it’s such a volatile volcanic island. There are such extremes between the lava and the cold in the north and the Northern Lights.

FR: You didn’t have that experience then, that experience of something out of the ordinary…like stepping into a different frequency.

KD: It did feel like I connected to the landscape and there was something clarifying about being there, because there is a starkness to things, and the contrasts between land and sea, and between the dark, volcanic rocks and sulphur pools, or green moss, or blue glacial water flood the awe chambers of the brain. It’s also a country where poetry feels close at hand. When I was there, the sagas and Icelandic poems came up in conversation a lot. Maybe that’s because that’s where my mind was at the time. One thing that stays with me is that when I was at a residency in Olafsfjordur, I asked someone who lived there to tell me about the tradition of hidden people, and he said he didn’t exactly believe or not believe in them, but he liked thinking of some presence in the landscape looking back, and I loved that sense of the world seeing.

FR: Who are the hidden people?

KD: This is from Wikipedia: “Huldufólk[ or hidden people are elves in Icelandic and Faroese folklore. They are supernatural beings that live in nature. They look and behave similarly to humans, but live in a parallel world.[3] They can make themselves visible at will.”

FR: I never thought to ask you these things when we were together seven year ago. But now I wonder how it happened, that the lava led you to Iceland. Lava is the life blood of Ore Choir, at least in my reading. In one poem the lava says, “They saw me as a soul…”, and in another poem it says, “I’m the earth’s aorta…”

KD: If I go back to your question, why lava…Your first insight was that The Glacier’s Wake and Ore Choir are siblings. In The Glacier’s Wake I was working on voice poems in the voices of a sycamore, a wasp, a glacier…and I just found writing in those voices incredibly generative. I don’t know about you, but in my training as a poet I’ve been discouraged from personifying nature. I think some people feel you risk sentimentality and people are skeptical, and I think rightly so. To me, a question that is vexingly productive is, on the one hand, I don’t want to project too much on something that’s mysterious, but I do want to reimagine a relationship to the natural world. I’ve been inspired by the writer Amitav Ghosh. In his new book, The Nutmeg’s Curse, he argues that it’s becoming harder to hold onto the belief that the planet is inert, that it exists only to provide resources. He says “the earth can and does act.”

Another poet whose work I love, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, often writes in the voices of different creatures, like marine mammals or coral. In a recent conversation with Adrienne Maree Brown, Gumbs talks about poems in which she wrote in the voice of a manatee, and she says, in that process, “it’s not to make the manatee more human; it’s to try to dissolve the idea of what human is because [that idea is] blocking the communion and right relationship that we have to create.” And when I heard that, light bulbs went off, and I thought, yes, that’s my experience in writing in the voice of lava. It’s not that I’m trying to make it human, although it’s kind of the only way I have to understand relationship in some ways.

I think of the lava more like a dragon. That’s the voice that I hear. I recently listened to an interview with Bjork and Robin Wall Kimmerer for Art Forum, which I highly recommend, and they also talk about the animacy of the living world. Bjork speaks about rocks as living beings.

What I took away from that was aha! Even though I was shocked by how consistent the voice of the lava was, and I thought of it like a dragon, an oracular voice, a booming voice, it’s kind of slippery, it’s not easy to pin down.

The other thing I had to contend with was at the beginning, when I started this, the lava was very jokey. It was making puns, and things like that. Then I became so attuned to eruptions that were happening across the world, and I would hear about people dying, and I just had to have a different sense about the destruction of the lava. It moved me, and I wondered “how do people contend with something this terrible and beautiful?” Ultimately, having this dragonesque voice made more sense because it’s terrifying.

FR: One of your poems has the line, “The lava IS the dragon.” I also loved, “I clot the sky with gold.” “I unmake eternity, rewild gold.”

This gets to erasures, lifting out of texts lines and phrases like “unmake eternity.” “I clot the sky with gold.”

I confess, I had not seen the word rewild before.

KD: And I see it everywhere. It came out of the process. Today it’s a principle of sustainability, rewilding.

FR: Clearly, we’re reading different things.

KD: Ha!

FR: We’re doing a little cross-pollination here. That’s one of the real beauties of your book. A lot of people are reading what you’re reading, but then there are people like me who are not. So that’s another gift that the book gives, this deeper knowledge along with a fitting language that may be new to some of us.

KD: There’s so much to read. There’s so much to read!

FR: So Iceland is beautiful and terrible and slippery and an aorta…

KD: And literary. I think it’s extraordinary. There’s a statistic that says one in five Icelanders publishes a book. It has a long history of storytelling and poetry, and valuing literature. And their literature is very much connected to the landscape. I have all these pet theories about that.

FR: Tell me a pet theory.

KD: Well, one is, I went to visit this place called Thingveller. This is the site of one of the earliest governments in Iceland, the Alþingi, and it was a proto-democratic structure. As I understand it, the different families or clans from all over Iceland converged at this one geographic spot at midsummer, which was where you could actually see the tectonic plates separating–a beautiful vista, with shallow water–you can imagine people gathering at this site to share news. And they had what they called the law rock where someone would read out amendments to the law and the godar (chieftains) would negotiate systems of government, rules, and treaties. You can still see the sites where the leaders would have their camps, and I couldn’t help imagining the poets who were there to recite the stories—and I wondered if they’d tried to impress each other to keep the crowds entertained. It’s very much tied to the landscape because they would perform against this natural tectonic amphitheater.

In my book, the translation I have of the Völuspá stems from the Poetica Edda where Odin resurrects this seer, the Völvá, from the dead so she can recite the poem predicting Ragnarok, the end of the world.

FR: Does Volva mean veil?

KD: The Völva is the seer or wise-woman. The original poem was composed after the Eldgjá eruption of 939 CE, one of the largest in history. You can imagine people trying to make sense of the terrible destruction as the result of an eruption; this tragedy is intertwined from the start of Icelandic society. At the heart of Norse mythology, Icelandic literature, there’s been this connection between the landscape and the volatility of the landscape and poetry.

FR: And what were you saying about Odin?

KD: In the poem, The Völuspá, Odin resurrects the Völva from the dead and asks her to tell the story of the end of the world. To do so, she begins with the origin of the world. It’s a poem that starts almost like Genesis: “In the beginning there was the yawning gap.” And she talks about formlessness and how things were formed and then she talks about the lives of the Gods and eventually she predicts the death of the Gods in the same poem. So my poem is a translation of that poem and also references another poem in the Eddas where Odin gains his own power of prophecy and insight.

FR: When I met you seven years ago, you read me two or three poems you were working on. Did those poems end up in this book?

KD: Oh, yes.

FR: Back then, as I listened to you read, I wasn’t thinking about lava, or Iceland, though you may have told me all that. I was just struck by how beautiful the poems were, and how surprising, with unexpected images and language. There was an otherworldly feel to them. I knew that they were erasures, and it seemed like something so difficult to me, as a writer, to draw those powerful lyrics from a prose text.

I’ve waited seven years for this book! You had already started when we met. How many years did this project take?

KD: This is about a ten-year project.

FR: Were you writing through the pandemic?

KD: No. The book had been accepted before the Pandemic. I didn’t make any changes after it was accepted. Working with this kind of form, you’re doing a lot of editing as you go. I did revise these poems during the process, but not as much as my other poems.

FR: Yes, because they’re erasures. Would you talk about your experience making erasures? I don’t know whether to use the word doing or making or writing…

KD: Ha! Exactly. Such a great dilemma! Sometimes I say composing.

FR: Did you find yourself surprised by certain phrases, words, thoughts in the manuscripts you used? Did you go into the manuscripts knowing what you wanted to find there and to say through the voice of the lava or did you just go into the manuscripts with no agenda except to discover as you went? I wondered if the mood and tone of the poems was somewhat dictated by your choice of manuscripts.

KD: Those are such good questions, because this process takes so many different steps. I think that as far as selecting the first texts, it was very intuitive. But I did try to find texts where the excerpts would stand alone and would fit with the other excerpts that I curated. So many of the first texts referred to lava in some way. There’s one poem where the text is from a murder mystery. And even in that excerpt, a dead body is found on a lava field. So finding the source texts was intuitive—I’d follow up on conversations with friends where they’d tell me about something they knew about Iceland, or I’d remember a historical event, like the summit between Reagan and Gorbachev in Reykjavik, then I would find a text. In terms of how that impacted whether I had an agenda when I went to the source texts that came from poem to poem. The more I worked on them the more I did bring my own impressions or ideas for the poems and I became more and more engaged with the subjects and the source texts. For example, I wanted to write about the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2010, when volcanic ash clouds caused prolonged closures of air space in Europe. When I found a source text about that eruption, I wanted to write a poem engaging with that article’s arguments about risk. So you’ll see the poem is about that.

Even when I would have a sense of the subject I wanted to write about, the process is so intense that it really was a give and take, so sometimes I would go there and I would have a word that I wanted and I would find the word, but quite often I might have a word I wanted but it would not be there. And there was no way for me to make that word, so it was almost as if the lava was pushing back, or it felt like how lava must push through hard rock and create an opening. That’s how it felt moving through those texts trying to find language. And especially because when I write I like to work with rhyme, and it was sometimes like the rhyme was also insisting, giving direction to the path, so there was this other layer happening. It was really a give and take. Toward the end of writing the book, I found myself wanting to assert a little more control and really engage with the source text.

FR: So you weren’t going to be pushed around by the source texts.

KD: Yes, although ultimately they did push me around.

FR: Of course they did. And they won, right?

KD: Yes. And that’s what I wanted. That’s actually why I went there. Using this process got me outside of my own control over poetic sound.

FR: Which poem came from the murder story where the body is found on a lava field?

KD: [Two go out], on page 36. The source text is an excerpt from Arnaldur Indridason’s Arctic Chill, translated by Bernard Scudder and Victoria Cribb.

FR: Would you read this poem to me?

KD:

Two go out

on the lavafield.

One invents a city,

one a fort.

One plans a feast,

one a siege.

The rocks

start to shine

in their eyes.

A plume of steam

rises

like a hired gun

out of the ruin.

FR: Hearing you read that poem gives me chill bumps. And then I look over at the visual on the opposite page of the composite of text, erasure choices and a photograph of an Icelandic landscape to find where ‘hired gun’ came from.

KD: I used individual letters…

FR: But they were in order, right?

KD: Yes.

FR: And on what page is the poem about risk?

KD: [Some scan situations] That one is on Page 58. The source text is “Inhabiting a Risky Earth: The Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2010 and its impacts” by Katrin Anna Lund and Karl Benediktsson. It was published in Anthropology Today, February 2011.

Some scan situations

for threat—

the whole landscape covert—

(an eerie appearance).

This taints the real

with the remotely possible:

a dream where planes

fall like rain.

Fear disorders

how we see strangers

and bullets fly

faster than reason…

Will you lean on each other

when I wreck the seasons?

FR: I hear your rhyming there, too. It’s wonderful to hear you read them!

When you start an erasure poem, are there any rules you have to follow?

KD: I think erasure practitioners love rules, but we don’t all follow the same ones. There are practitioners who would not go down to the letter. They would only go down to the level of the word. And there are others who would allow themselves to move vertically down the page as well as horizontally. For my erasures I did have to move horizontally across the page, always right to left, and I was allowed to go down to the letter.

FR: Any other rules?

KD: For my poems I didn’t want to have a lot of phrases from the original text, so I just intuitively tried to space things out.

FR: And some poets go vertical?

KD: Yes. One poet who is writing beautiful erasures these days is Lisa Huffaker. She creates these gorgeous diagrams of circles and arrows that guides you how to read the text all across the page. But there are so many poets exploring erasure.

Some other constraints: I started to pick longer and longer source texts, and my collaborator, Kevin Tseng, gave me some limits on that. It was very important to me that you could see the source text, and have an index so people could look at the original, and he suggested I limit the size of the source text in order to do that.

FR: Ore Choir is a collection of lyric voice poems, it is erasure poems, it is a hybrid book, and it includes a section of scholarly information about the texts, and several pages of full color glorious pictures of Icelandic landscapes that were used in the composites. Have I left anything out?

KD: Laughter. It’s many layers.

FR: When I think of you and your collaborators, I think of the lines in a poem on page 48:

Co-dreaming

these trans-

formational odes.

That’s what you and your collaborators were doing. Co-dreaming.

KD: Yes. That’s what I was hoping. I think that poem is an ars poetica for sure.

I would say that the process of making this book was mystical. I think the use of erasures is a mystical process. It’s almost like working with a ouija board where you’re listening to the rhythms that are coming forward and trying to navigate towards whatever word or letter comes next.

FR: Would you say more about how the process was mystical?

KD: First of all the process was an absorbing method of working so that when I was involved in working on a new source text I would quite often be so absorbed that if I heard any noise or someone called my name I would jump out of my skin. And then the fact that the voice was so consistent was also very mystical to me because I’ve always struggled to know my own voice in poetry. It always feels like when I’m approaching the blank page I have no idea how to find the voice and begin the poem. It’s a real struggle for me to find that. But in this process I never had to struggle to find the voice. It was very consistent, which was so strange.

There were these moments when I would get into the source text and I would have my own agenda and I would want to use a specific word and the letters wouldn’t be available to make the word I had in my head. But it almost felt like a kind of translation where if I sat with it long enough, a word would emerge that was even better or that had more depth than I could have imagined for the point I was trying to make. I had experiences of the hair standing up on my arms when I would find a word that fit the scheme.

FR: Would you give an example of not being able to find the word you wanted, and then having a word emerge that was not only better, but that had more depth?

KD: I was working on the poem [I adore canoes], which is an erasure of T. Thordarson and G. Larsen’s article: “Volcanism in Iceland in historical time” Volcano types, eruption styles and eruptive history” from the Journal of Geodynamics. This is probably the strangest poem in the book, because I didn’t know why it seemed right that lava would love canoes, but I liked the sound of it as a first line (now it makes me think of a pivotal scene in Sara Dosa’s Fire of Love, when Maurice Krafft tries to canoe an acid lake). I was trying to convey how the sound of rowers on the surface of the water, an action that was such a contrast to lava’s own disruptive progression, gave the lava a kind of joy. At first, I was looking for the word “opiate,” but I didn’t have any “p” available in the small section of the sentence that was available to me. I had a lot of “l”s and “i”s, so I looked up “li…” in the dictionary, and I found the word “lithic,” which relates to lithium, which is of course a healing medicine for some forms of mental illness. Lithic can also mean “turn to stone,” which is what lava does. So it seemed that the text yielded a far more resonant and precise choice of words than opiate.

FR: One of the things I jotted down in my notes was that in the process of making/ composing these erasures you seemed to become the lava, or Iceland, as if there was a merging of you with the voice you were writing from.

KD: Right. I would hesitate to say Iceland because I’m an outsider, but definitely I was trying to inhabit lava in some way. What’s interesting is that it’s almost like I’m asking lava’s opinion on these human difficulties. And because lava is on such a different time scale, it was like asking an oracle. It was taking this deep time perspective on issues like loneliness or art or history or leadership or government or climate change or nuclear war. Things like that. By consulting the lava, mostly I was just having this more cosmic perspective about these things that seemed immediately troubling.

FR: So when you talk about lava as being oracular, you are talking about back in ancient times when people went to the Oracle of Delphi with questions of import.

This really was, I’m not going to use the word journey, it’s used way too much…

KD: …an exploration, a meditation, an inquiry…

FR: Yes, an inquiry, And you are a person who could give me the entire etymology of the word inquiry, right?

KD: Not off the top of my head, but I bet it’s a good one.

FR: So the lava is almost speaking from the place of eternity? It has nothing to do with time?

KD: It’s funny, because someone read my book as being all about time. So in fact, because lava is operating in a different time scale, it makes our sense of time and how we are attached to time more apparent. The lava is not attached to time as much because it’s operating on deep time.

FR: What does that mean…deep time?

KD: So the way I think about deep time is theologic. The fact that you can look at a rock that’s millions of years old, and you can even hold it in your hand; that there’s this convergence of human time scale with…the span of a human lifetime or the generations around a lifetime…we’re encountering all these things that have been here long before humankind existed, and will be here after humans are gone…so deep time is thinking about how brief a thing humanity is. That’s kind of what I mean by it.

FR: I liked what you said earlier about one writer believing the earth can and does act, which implies it has its own consciousness, its own intelligence. In some ways your poems do pierce through barriers most of us don’t think about. Maybe the people who are reading the same things you’re reading are thinking about these things. Maybe the climatologists are thinking about these things.

KD: There is new thinking about this. I’ve been working on an essay that asks; what is the use of poetry in the face of climate change? Trying to come to terms with the key words, 2 degrees celsius. In the climate world, that’s the tipping point. If the global surface temperature rises above 2 degrees celsius, we’re going to face all kinds of consequences we might not have been able to imagine. My essay asks, how does a poet define that term? In order for us to think about that, we have to re-think everything. To stop this from happening would require a complete restructuring of our economy. What does poetry offer in the face of that? In the essay, I make some arguments about non-linear thinking.

FR: Let me ask you some basic questions. When did you start writing poetry?

KD: I think I wrote my first poem when I was seven. It was a poem about my grandmother. About a rainbow. But I really started getting into poetry in college. I had taken a fiction workshop and it was almost like wearing a shirt that kinda fit, but didn’t feel right. And then I took a poetry workshop and it was like, ohh…this is how my mind works. This is it. I did my undergraduate thesis on Marianne Moore. I think Ore Choir, as strange as it sounds, is my most Marianne Moore-esque book. She was someone who did a lot of research, and she also used language that she pulled from texts that she used in research. This book is all about that and it’s also very interested in precise vocabulary. I was also very interested in other erasure practitioners, like Mary Ruefle and Tom Phillips. Early in this project, I got to meet the poet Jen Bervin when she gave a reading at my school, and the way that she approaches her books, not just the erasures but her other projects as well, were influential. I’m also a fan of the poet a. rawlings, and that poem about co-dreaming transformational odes is an homage to her.

FR: What drew you to Marianne Moore?

KD: I was trying to choose a poet for my undergraduate thesis. I was always drawn to Elizabeth Bishop and I thought it would be interesting to look at her influences. So I went to look at Moore, and I found her poem; Poetry…I too dislike it, and something about that just drew me in! That was how it started. I did my undergrad in St. Louis and Moore was from there originally. I think her poem, “The Fish,” as soon as I read it, it unlocked all these doors in my brain, and I wanted to keep going.

Katy Didden is the author of The Glacier’s Wake (Pleiades Press, 2013) and Ore Choir: The Lava on Iceland (Tupelo Press, 2022). Her poems and essays appear in journals such as Poetry Northwest, Ecotone, 32 Poems, Diagram, The Sewanee Review, and The Kenyon Review, and she is one of the co-creators of Almanac for the Beyond (Tropic Editions, 2019). She is an Associate Professor at Ball State University where she teaches Poetry and Creative Writing and the Environment.