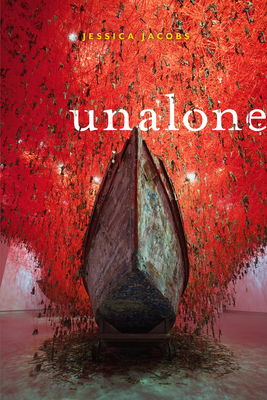

NM: Thank you, Jessica, for talking with us about unalone, forthcoming from Four Way Books in March 2024, which Sean Singer praises as a “fascinating, crafted and authoritative book.” The arrangement of unalone follows the Book of Genesis as it tracks your journey/genesis to a palpable spiritual connection and community that has radically changed the trajectory of your life and work. Was there an initiative moment: “How it finds you: at attention: /the hair on your forearms, up/the nape of your neck, your whole scalp /prickling…” or a growing awareness of this presence?

JJ: In 2011, I spent a month alone in an isolated cabin in New Mexico’s high desert, finishing the poems that would become Pelvis with Distance, a biography-in-poems of Georgia O’Keeffe. There was no internet, no phone, and my closest neighbors were five miles away by foot. As I read and wrote and followed the runs of deer and elk, as I spent hours watching light move across the canyon floor, the silence made way for large questions: Why am I here? What qualifies as a life well lived? What choices can I make that serve more than just myself?

NM: The desert has a long history in literature and in both the Hebrew Bible and New Testament as a place where God speaks. Did that occur to you while you were there?

JJ: Having walked away from any formal practice or study of Judaism as a teenager, at that time, I had no idea that going to the desert was a biblical act.

NM: If I’m correct, the Torah was given to Jews in the desert.

JJ: Yes, it was given to the Jews at Sinai, after they were freed from their enslavement in Egypt. My own far smaller journey was less a moment of revelation than an upsurge of open questions. And upon my return, I found that literature, the closest thing I’d had to religion at that point, felt suddenly thin. I wanted to tap into more tested sources of wisdom and began to explore, reading up on the tenets of Buddhism and learning about the life and teachings of St. Ignatius. But before I gave myself to another tradition, I felt I should spend at least a little time learning about my own. So, in my mid-thirties, I read the Torah all the way through for the first time and was astonished by how this ancient text seemed to speak so directly to my life and the larger world. And because I can’t fully understand something without writing about it, I began drafting poems in conversation with these stories.

NM: As most of the poems are prefaced by epigraphs from the biblical text, the conversation following in the body of the poem is believable and nuanced; slang, juxtaposed with biblical text gives the poem texture and distinguishes the speaker’s voice: “It’s the tense/ of done and dusted, of bet/ your ass and bottom dollar…” from “Elegy in Prophetic Perfect.”

JJ: I’m a fan of the elevated diction and cadences of scripture in translation, as well as the intricacies and repetitions of Biblical Hebrew. But I was writing these poems to better understand how these stories informed my contemporary life; so to communicate that to myself, as well as to a reader, I needed moments of daily language. As I wrote and revised, this contrast also provided a kind of generative tension.

NM: I’m intrigued by the investigations of the binary self that run through unalone as in “In the village of my body, two people//vie for the throne, box-sprung/ and gold-leafed though it /is.—”

and of a Binary God as in “Covenant Between the Pieces”

And God didn’t

even have a definite name

—bound to Abram was אֵ֣ל שַׁדַּ֔י El Shaddai,

whose meanings are slippery as that channel through the animals:

“God Almighty” and also “The Great Breast,”

each integral to the other:

Does unalone suggest it’s possible to reconcile opposites or at least integrate them: “balance, etched on one side; on the other, integration.”?

JJ: Growing up, much of my early life was coming to terms with disparate, often contradictory-seeming parts of myself: the bookish geek and the multi-sport jock, the queer kid longing for connection and the introvert who was most at ease in solitude. At this point in my life, when I’m thankfully far more comfortable in my skin, I’m most interested in integration, in learning how these facets might best join to make a whole.

NM: Is this some of the impulse behind your founding of Yetzirah?

JJ: When I began writing these poems, I wanted to learn from poets who’d done similar work, to be in conversation about the ways in which connecting with these texts and this tradition could be life-changing. Given my admiration for affinity-based groups like Cave Canem and Kundiman, I was surprised to find there was no such group for Jewish poets. Yetzirah was created to fill that void, and at our inaugural conference last summer many participants said it was the first time they felt they could show up fully as both a poet and a Jew and further explore the relationship between those parts of themselves. I felt the same way and I’m honored to be a part of this growing community.

NM: Thank you, Jessica, for this wonderful conversation, and for sharing these three featured poems from unalone with Plume. We look forward to its debut from Four Way Books in March 2024!

How Long Before

To move in the wet heat of Florida summer is to be carried

in the mouth of an animal. But inside my parent’s house,

kept chill as a mausoleum, my mother paces and weeps

in a ragged nightgown she refuses to change, her hands

two anxious dishcloths trying to wring themselves dry.

Because I am not the person I’d like to be, I shut the door

on this, on my father’s poor job of pretending

not to cry, and, between fences draped in air potato vines

beetle-eaten to a path of tattered valentines, run

as though I could leave any of this behind. As Joseph tried to

when he named his first son Manasseh, He-Who-Makes-

Forgetting, a word that hints at memory evaporating

like water from a sizzling street, that heat

hungry as the silverfish swimming

my childhood books, leaving holes in all the old stories.

But to name someone after what you say you’ve forgotten

is to make of them a neon arrow to the relentless past,

one you’ll someday return to. This is not that.

The mother I’ve lost is lost for good. The only cure

for such decay is its completion, when she’s forgotten

even forgetting. In the mountains I’ve made my home,

vine barrens of kudzu, invasive as her illness, mask

every gall, burl, and blight. So come, high-climber,

you foot-a-night-vine. May all her buried memories remain

for her unmarked, unnamed. Cover it all

with your nullifying green, be a sea that waives over everything.

And if it brings her peace, let her forget even me.

Like Water on Its Course

“Because you sped toward your anger like water speeds on its course, you shall no longer receive the

abundance that was meant for you.”

—Jacob to Reuven, his firstborn son (Rashi on Genesis 49:4)

א.

Every page, every day, a rigged game: each human a character

pricked by sentience, conscious of the joystick’s jerk.

Even before birth, Samson was blessed into service,

his parents’ given holy notice. God’s will conducted

the command center in his head: There’s a lion in the vineyard,

Samson; tear it asunder. Here’s the jawbone of an ass; there,

the faces of your enemies; and here’s the arc of the swing.

The more chosen you are, the less free you are

to choose. And by chapter’s end: betrayed, shorn, blinded,

and dead by his own God-directed hands—

but a murderer, too. That fact just as true.

Or is a sin compelled somehow less sinful?

ב.

For if not to God, aren’t we captive

to our minds’ wiring, our bodies’ chemistry, the family

we’re born to? The anger that is my birthright—

passed down from my father and his father unto him,

corrosive, self-starting—it biles up in me. A surge of fury,

I grow strong with it: my scalp singes and tightens, my muscles

flex and sing. I try to soothe it with reason, to bury it

in my chest, but it burns there like a second heart.

ג.

The lion was the only kill Samson hid

from his parents. Left to rot until bees hived the mighty ribs,

when Samson plunged wrist-deep into the remains,

he emerged with palmfuls of honey—a false balm

that roiled his gut. For whether Samson was gripped

by God or rage, the lion he killed was just as dead.

ד.

Which part is God: my temper or my tempering of it?

I need to believe it’s both, that even the worst of me

is somehow holy. That I can channel what I cannot change.

In the Breath Between

“Everything can be taken…but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in

any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

—Viktor E. Frankl

All is foreseen, said Rabbi Akiva,

and freedom is given, holding

in each hand the tail of a horse

straining away from the other.

Abandoned, enslaved, imprisoned,

and exiled—the first horse

was everything Joseph suffered.

Yet when he could have killed

his betraying brothers with a nod

of his head, he forgave them instead,

saying, It was not you

who sent me here, but God. His choice

of mercy was the second horse.

If all that happens

is fate, who we are

is the meaning we make from it.

And in that breath

between what’s done to us

and what we do with it

is the crucible of our becoming.

You can learn more about Jessica Jacobs at https://jessicalgjacobs.com