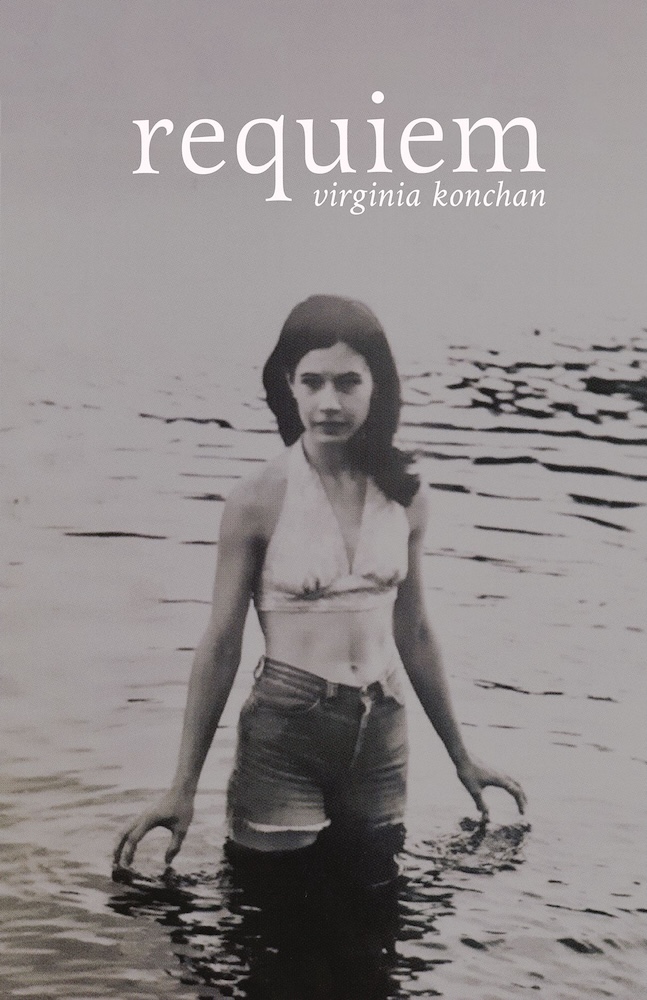

Virginia Konchan, Requiem.

Carnegie Mellon University Press. March 2025.

Reviewed by Heather Treseler.

“I have already faced The Worst… [and] can enjoy life simply for what it is: a continuous job,” Sylvia Plath wrote to her mother during her first Fulbright year at Cambridge University in 1956. Suffering from a dorm without central heating, standoffish dons, and a bout of “colic” for which she was hospitalized, Plath felt bleak that winter, according to her biographer Heather Clark, who vividly recreates her subject’s life in Red Comet, The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath. As an accomplished poet and fiction writer, and as young woman with outsized ambition, literary talent, and sexual hunger, given women’s culturally prescribed roles in postwar America and England, Plath wasn’t being hyperbolic in noting the sustained labor behind all that she had achieved—and experienced—by the age of 23.

I couldn’t help but think of Plath’s remark as I read Virginia Konchan’s Requiem, an electric new collection of poems that grieves for a mother and for a generational experience of early womanhood, with allusions to Plath’s poems and version of disenchantment. Indeed, fast-forward from 1956 to 2025: “continuous job” is still a refrain among women writers, and perhaps especially those from Konchan’s (and my own) “Oregon Trail” generation of Xennials, born between 1977-85, who have straddled the analog and digital divide; the radical escalation in the costs of education, housing, and healthcare; and the attitudinal shift from Gen Xers’ skepticism to Millennials’ optimism-against-the-odds.

When my peers describe their “continuous job,” they aren’t just referring to the day jobs they perform to pay the bills. They are denoting all the auxiliary tasks they do to keep that steady job, to write (often serving as their own copy-editors, designers, publicists, and distributors), and to maintain personal relationships.

Is this feminism under neo-liberalism?

Before there were supermoms, side-hustles, and GoFundMe, there were women of Plath’s vintage who—even when white and nominally middle-class—didn’t have access to the elite education, peer networks, and social approval of their enterprise enjoyed by many of their male counterparts. Plath and her contemporaries were expected, alongside their professional aims, to be dutiful daughters, supportive spouses, nurturing mothers, and pillars of their communities. Plath’s superficial compliance and rebellion from these roles shaped her life and suffused many of her poems and her wildly successful roman à clef The Bell Jar.

As I read Konchan’s Requiem, which adds to her four other books of poetry and her collection of short fiction, Anatomical Gift, I wondered: how much has changed for the woman writer since 1956? This seemed especially apt, given that Requiem firmly establishes Konchan as one of Plath’s heirs.

We see this inheritance stylistically, in Konchan’s associative leaps and range of learned references, and substantively, in her bristling insight into women’s psyches, their conflicts and longings. Like Plath, she explores the primal instincts hidden in civic life; the rigid cast of familial, social, and romantic roles; and the labor, affective and actual, that women are often tacitly expected to perform in the workplace and homeplace.

Konchan brings these dilemmas into the 21st century where “connectivity” enables a further blurring of private and public, the subjective and the social. This includes the curated version of our lives that many of us offer, on social media, for public consumption—even with its unseemly appetite for pathos, bathos, and erotic frisson. In “Pastorale,” Konchan writes:

Stalked by paparazzi of my own making

in a hyperlinked garden of forking paths,

I’m chain mail in search of an addressee.

… Serenity now, I say

to my alter ego, my father’s incipient

dementia, my mother’s brain tumor.

…

There’s no pill or product left:

I cordon myself off, to grieve.

I need a strong French cheese,

stern advice, a retirement plan

from all the helping industries.

Konchan’s book, galvanized by her return to Cleveland to care for her mother, entering hospice, and her father, struggling with his own decline, brings a postmodern sensibility (Diogenes and dive bars) and a Plathian jauntiness to a dire situation. Like Plath, she ironizes pop psychology’s doctrine of positive attitudes—and Teflon cheer—in terrible situations. In the triple rhyme of “grieve,” “cheese,” and “industries,” she frames the obscenity of mixing grief with the consumption rituals of “self-care,” indicting consumerism disguised as emotional regulation.

Konchan also animates midlife grief as an Xennial. “Stalked” by online presences, a “paparazzi of my own making,” she recalls the practice of “chain mail,” a feature of an ‘80s childhood, in which letters were addressed to cohorts of friends’ friends, a correspondence marked by the sunny trust of another era. (The other meaning of “chain mail,” armor of loosely interlocked metal rings, applies here too, given the narrator’s vulnerable defenses.) Similarly, when the speaker quips “serenity now,” she echoes both the comic imperative of Frank Costanza in the ‘90s hit sitcom Seinfeld and Reinhold Niebuhr’s solemn “Serenity Prayer”—both utterances inadequate to the pressure of caring for parents in acute need.

Alongside these cultural touchstones, Konchan grapples with supporting loved ones facing their mortality. Admitting that “there’s no pill or product left,” the narrator yearns for the space “to grieve.” But to do so, she needs “a retirement plan / from all the helping industries.” For millions of Americans without bounties of wealth, that space doesn’t exist. The resources of Medicare (and/or Medicaid) are often supplemented with the caregiving of daughters, sisters, aunts, or other female kin. Konchan looks candidly at this commonplace crisis and the socialized demands it often makes of women.

Indeed, while Requiem is centered on mourning, it articulates generational grievance—along class and gender lines—as much as private grief. In a nod to Plath’s “The Applicant,” Konchan’s own poem “Applicant” considers the sexual marketplace, but doesn’t have the “rubber breasts or rubber crotch” or the haunting query—“Will you marry it?”—of its predecessor. It does, however, take on the absurdities of wage labor, surveillance capitalism, and fairytale mythos: an appetitive network she longs to escape.

I am not well enough to perform my duties,

I said to my boss. He said, do them anyway.

As a teen, I worked at Bed Bath & Beyond.

I wandered around housewares, hoping to be

helpful to someone looking to buy a crockpot.

Later came jobs as a nanny, typist, and barista,

surrounded by the din of children and machines.

…

Do you think I was made for, or long to belong

to this world, a parade of melodramatic scenes?

Like the time my ex-husband and I wrote our

initials in the sand on our Kauai honeymoon,

then photographed it, thinking about forever:

the tide erased it, and later, my memory too.

Show me the way, Google, to my best life.

Watch over my ongoing commodification:

hold me in your gaze, the way lovers do.

Sick days can’t be taken with impunity in many service jobs—retail, childcare, or food service—and sacramental marital moments can go out with the tide and the data plan. Plath’s “Applicant,” which appeared in her collection Ariel, delivers a mock-sales pitch to a male addressee about a woman’s desirability: “It can sew, it can cook, / It can talk, talk, talk. // It works, there is nothing wrong with it. /… / My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” But in Konchan’s version, the final addressee is Google, which has replaced God as the purveyor of wishes. It alone will remember the speaker’s yearning, all her desires’ destinations. While in Plath’s poem the female is a complex machine of social, sexual, and practical labors, a “living doll,” in Konchan’s poem, the narrator resists the mechanization of her labor and yet wants, in the end, to be wedded to her search engine.

For all their truth-telling, Konchan’s best poems do offer the bracing linguistic transcendence one finds in Plath. If mythologies and machines—from God to Google—offer no relief from capitalism’s cruelties, there is, at least, the redoubt of thought and its compelling inscription: the expressive freedom valued among our most sacred rights. In one of the book’s closing poems, “Gloria Patri,” originally featured in the New Yorker, the narrator finds refuge in an unlikely setting.

Glory be to god for this quiet, cheap hotel room:

only music the mini-fridge’s vibratory drone,

creaky plumbing groaning through the walls.

We underestimate the perfect peace of objects.

Before me was another traveler: after I leave,

hundreds of others will arrive, anonymously,

drink sink water from disposable plastic cups,

recline on bleached sheets, stare into the void

of a generic landscape painting across the bed

while contemplating the disaster of their lives.

. . .

I’m at an age where everyone around me is dying.

I’m at an age when the recited script isn’t enough.

Glory be to god for logjams, the antediluvian dark,

for being a supply of goodness outpacing demand.

The hotel room prompts the narrator to mull souls’ passage through its temporary habitation; she joins a loose congregation of fellow-travelers who have studied these same walls and its generic art, taking reprieve from their lives. In hailing the “supply of goodness outpacing demand,” the narrator also dreams of living in another system of exchanges, beyond the rudimentary ones that shape our material lives and fortunes.

Fittingly, the poem turns to a psalm in the Gideon Bible that the narrator finds in the nightstand: “whoever dwells in the secret place of the most High / will abide under the shadow of the Almighty.” The narrator meditates on this portion of Psalm 91: “a freely given gift whose only precondition is belief / … put there for safekeeping, for salesmen like me.” Here, the poet acknowledges the vast spiritual hunger, the force behind faith—and the shoe leather effort in the “continuous job” of living—that Plath also recognized. Konchan expresses that yearning with an inflection attuned to her generation, offering us the unsettling power of her secular psalms: postmodernist songs to grace our passage.