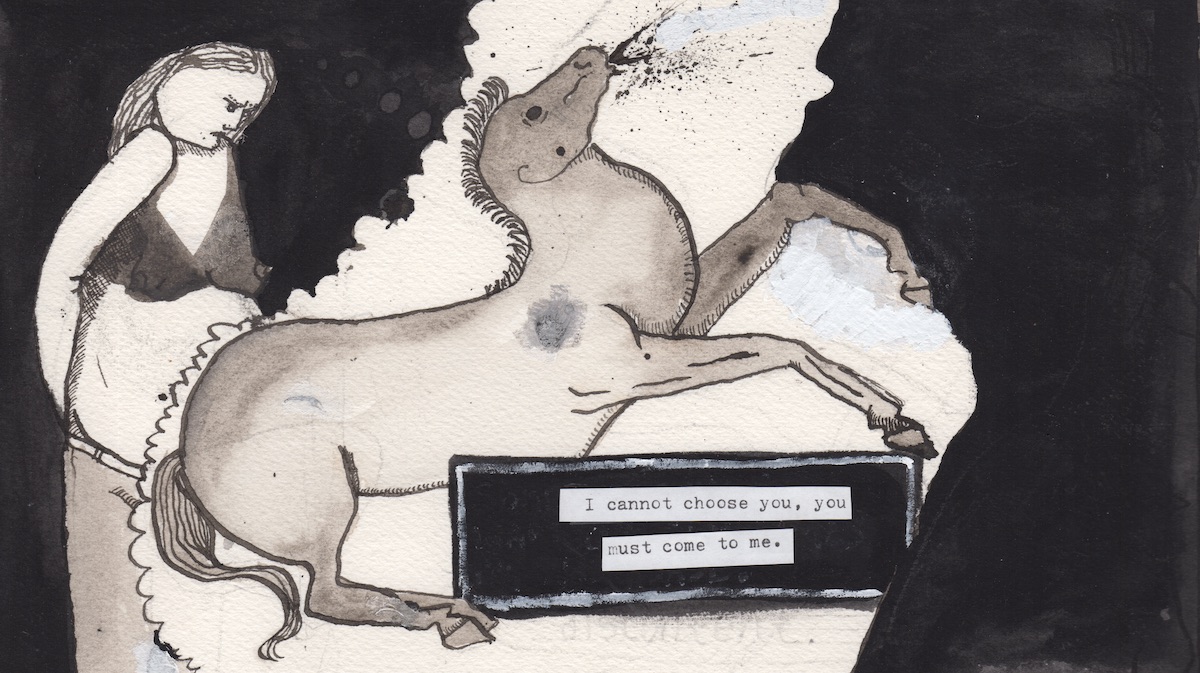

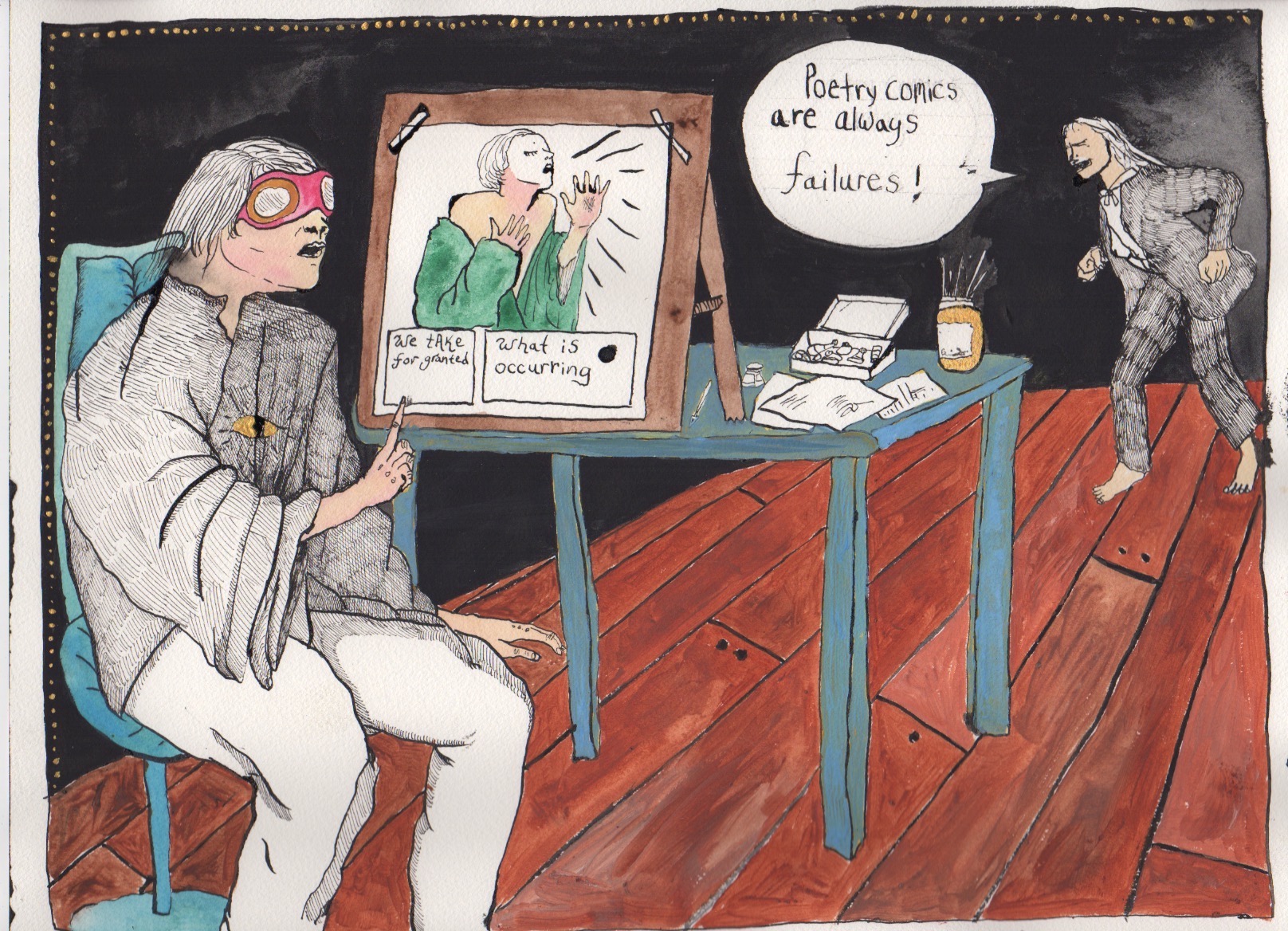

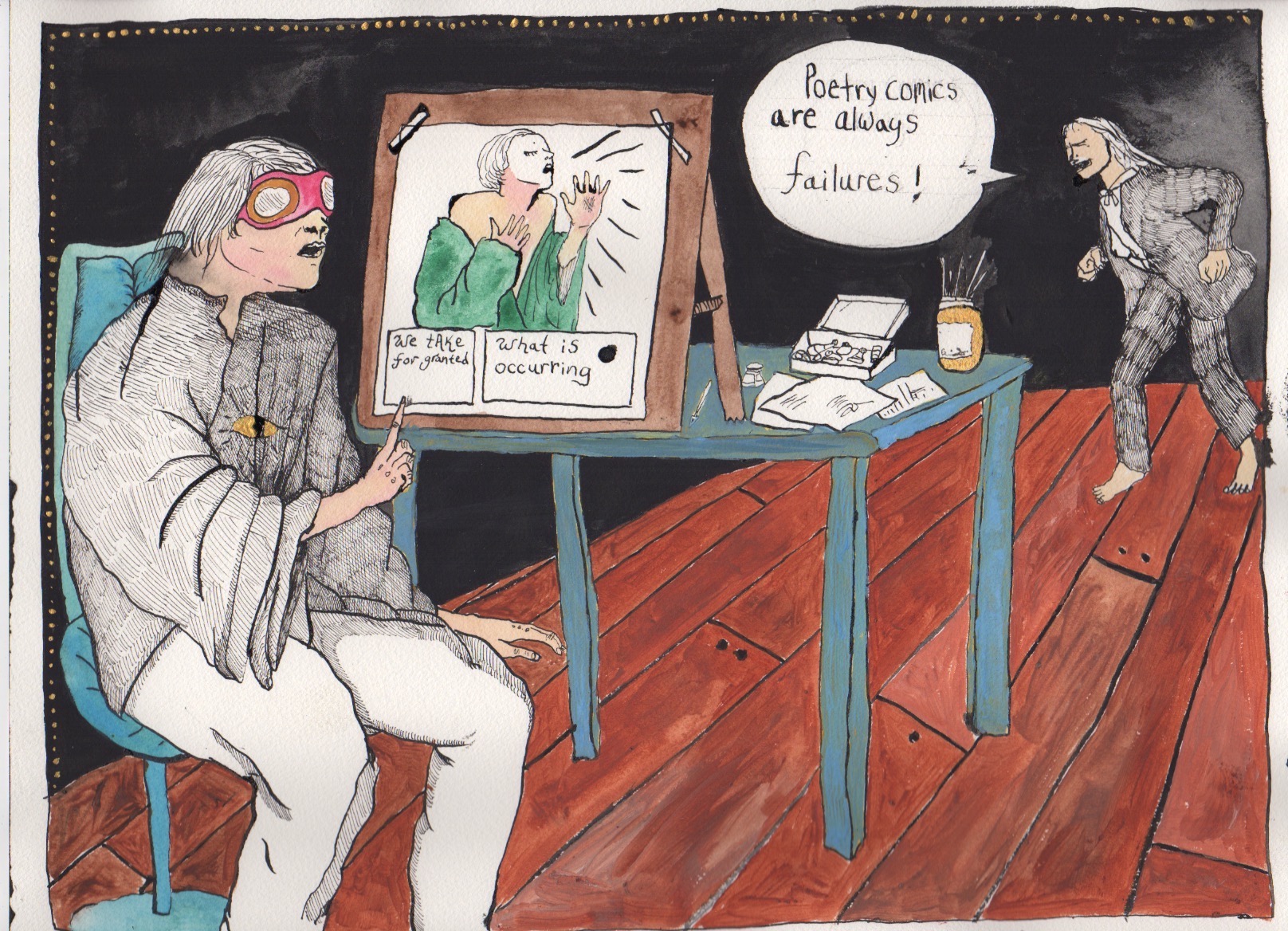

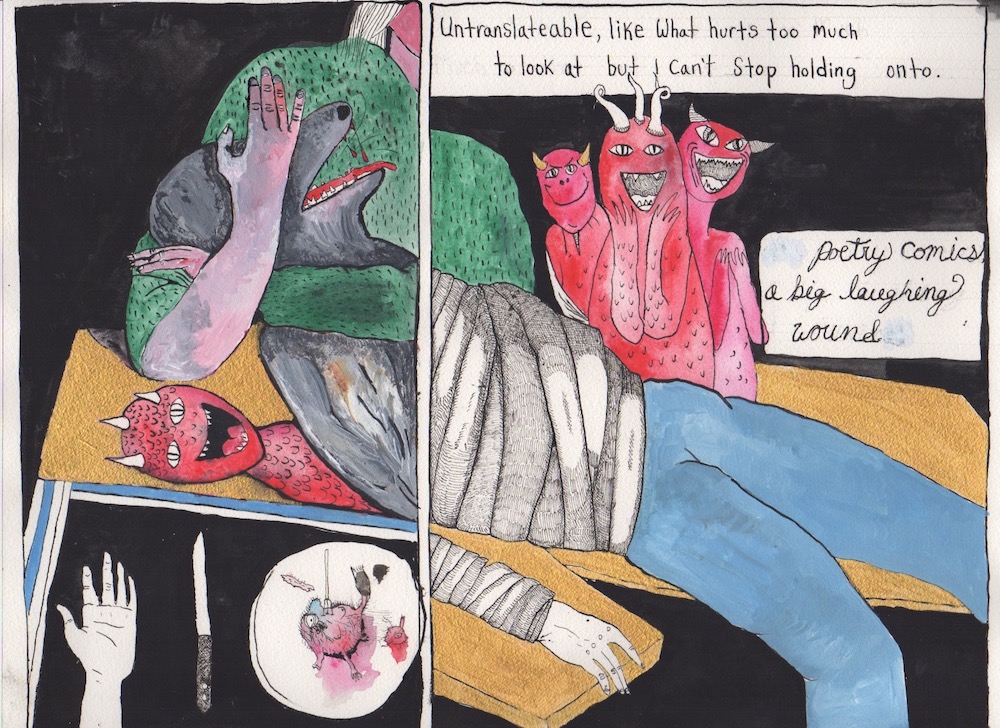

In addition to her gift for writing moving, lyrical poetry that captures her subjects with memorable, raw imagery, Bianca Stone also possesses a commensurate artistic gift for drawing and painting, particularly when it comes to her poetry comics. In her essay “Why I Make Poetry Comics,” which is essentially an ars poetica, Stone explores her difficult obsession, her agon, with the genre of poetry comics itself, a genre she finds “troubling” and “close to impossible.” Her struggle to capture what she finds so difficult as an artist and poet translates into deeply evocative images and captions that are as much epigrammatic poetry as they are “poetry comics.”

–Chard deNiord

Why I Make Poetry Comics

Bianca Stone

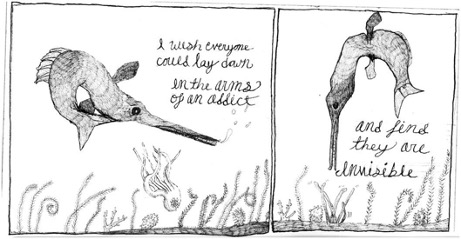

I think some part of me that was always emotionally stunned beneath a tarp wanted to make poetry slide into art, from very early on, as relief. I recall finding a red notebook from my childhood, small enough to fit into your pocket, of which I had written on the cover “The People of Distress.” On every tiny page a new distinct figure was drawn with a name underneath it. I have no idea or memory of what any of it meant then, but it mixed itself between metaphysical and childish text that seemed to be imitating poetry blurbs, which were about me. The great poet Reginald Shepard said in his essay Why I Write, “My aim is to rescue some portion of the drowned and drowning, including always myself.” I, too, stand in this position of rescue, from the watery and languageless depths, to save some element of myself and those I love. It seems as if, all these years later, I am still inventorying these sinking people of distress in the form of poetry comics.

People ask me, What are poetry comics? And one might as well ask, “What is poetry?” “What are comics?” They are not easy answers. But the questioning is important. And I am always grateful. I would rather make friendly philosophical quarrels about the function of language than I would defend the thesis of poetry comics. I would rather scrawl the absurd onto paper, thrust it into someone’s face and demand they feel something indescribable, rather than write a clear definition and send them on their way. I would rather mirror their bizarre situation of being alive with an inadequate mouth than reflect some false sense of fixed meaning toward them. We have television for that.

What I want to do here is simply explore poetry comics with you, because I, myself, am exploring them, as I have been forever. I don’t know what they are, or why they matter or how long I will stand them. I know that we shift and evolve in our genre bending, in our expectations of art. I know that poetry is shifting, as it always has, while also holding fast to its fundamentals, its core, its strange specific soul. I know that poetry comics are just one branch on a tree of human exploration. I know that poetry comics are not poetry. And they are not not poetry. Poetry comics confront two sides of our brain, and like existentialism, reject a systematic philosophy, or any vow to define the world of human existence with a neat formula that limits metamorphosis.

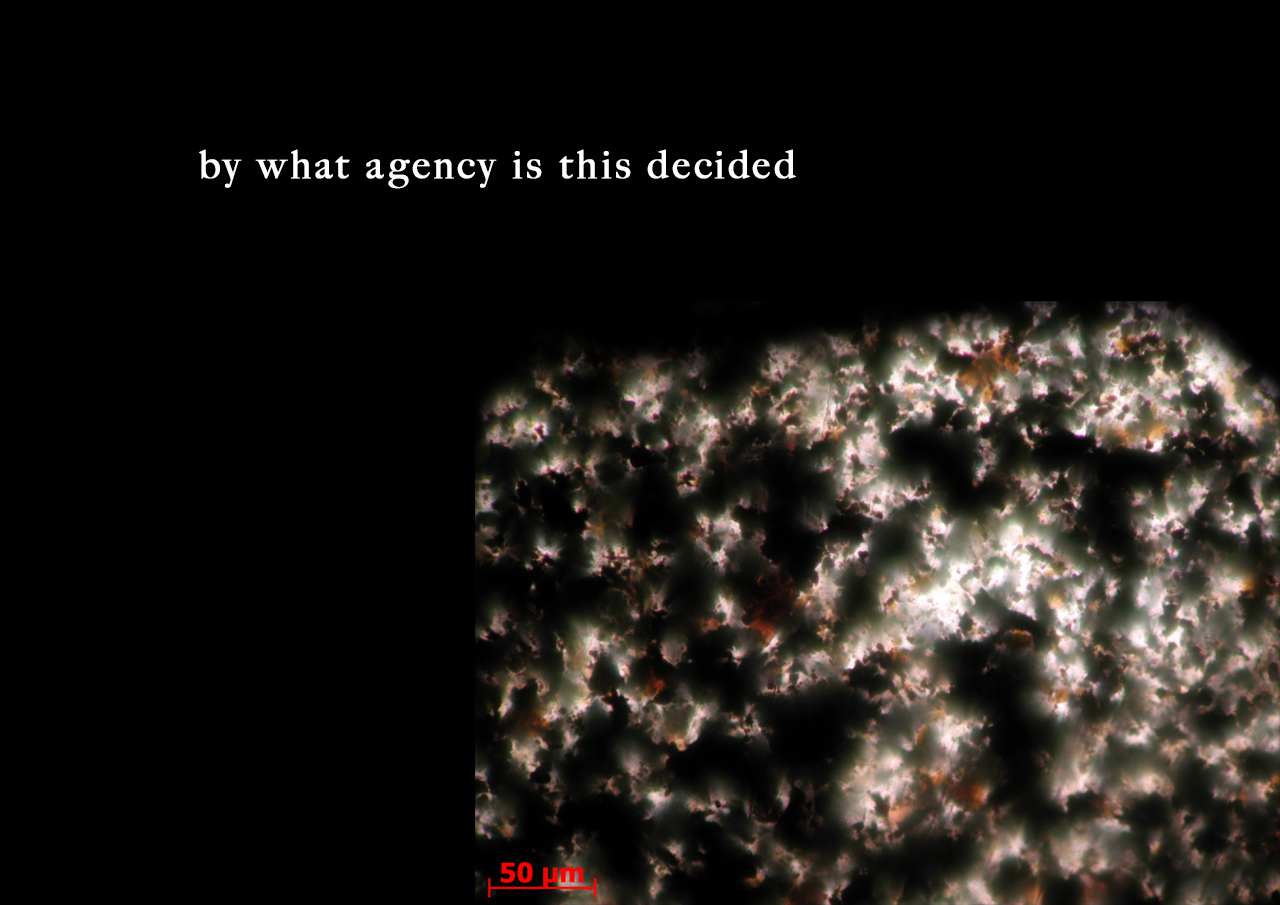

To practice poetry comics is to talk about poetry comics. Poetry comics—which will always be, in some way, unloved and feared, just as poetry is. “The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.” Camus wrote. There is a human need born out of the practice of poetry, and it is absurd. The profound silence of the world that is always at the periphery of our consciousness, no matter how hard we attempt to ignore it, wants to be looked at. We are filled with an excruciating longing that no one outside of ourselves will ever be able to quench. This is a fact we somehow know inherently as an unreachable goal, yet here we are, obsessed with the impossible task of still trying.

Poetry Comics and the Dyad

Poetry comics are born out of confrontation, raised in absurdity and kept in the unruly containment of the panel. They embody a contradiction of two vastly different modes of communication: pictorial and typographical. They are the child of each of these genres, with (for me) the stronger genetic features of poetry. “[The image] … drops down references in different registers than the text does,” says Claudia Rankine about using images in her books. “It seems like a door but the door actually is leading right back into the text.” The confrontation of image and text demands the reader to reconcile two opposing forces: picture and word. The results of the disparity between text and image, that are not joined simply to inform, often seem abstract and strange. But to be effective, the poetry comic must engage with the absurdness of human experience, which by its very nature is contradictory. Finally, to be reachable to the reader, the poetry comic contains its incongruous self in the panel—which is its frame, its stanza. Even if that panel is simply a canvas, or the confines of a book’s page.

My friend and poetry comics colleague, Alexander Rothman, is much better, (and more sane) in his attempt to define the poetry comics genre (or as he prefers “comics poetry”). He notes too that

“…some paratactic order underlies all poetry, where we hold a

thing in the mind, turn to another, hold it alongside the first. Something

bounces between them. They complement each other, or contradict each

other, or reinforce each other or change each other. They resonate. And

since we’re talking about a hybrid form, it’s worth saying that this is how

successful hybridization works, too, in terms of its constituent parts.

Really it’s the foundation of human thought. We know by comparing, I and thou.

So, comics poetry. It asks, what else can comics do?”

The genre of poetry comics was born out of a realization that the two genres function similarly. Poetry comics are poetry because they disassociate, dissolve logic, syntax and information-giving. (They are based in the lyrical, not the narrative.) They are comics because they are always in some sense, relying on an element of image and sequence, even if that sequence is within a single frame. (Poetry comics might also be comics because they are irreverent and dramatic—almost camp, almost opera, linking and unlinking meaning.) But this new genre’s potential is much greater than the fact that (poetry and comics) function in underlying, similar fashions—mainly that they rely on negative capability, which I will expand upon later—the impetus of poetry comics born of a realization of their mechanistic similarities.

It is true that poetry comics insist on confronting a deeply fraught relationship with mind and language–an anxiety about our inability to truly communicate with one another. Matthew Zapruder says of poetry in general: “In following what is beautiful and uncertain in language, we get to a truth that is beyond our ability to articulate when we are attempting to ‘use’ language to convey our stories or ideas.” Poetry comics are an extension of this intellectual effort to convey the contradictory nature of human existence. The mediums of poetry and image are each uniquely situated to communicate something beyond language. Together, they have great mystical potential, they push against comfort, are impossible to do without failing, and like visions, like fever dreams, they exorcise something to the page. “There is a sense in which both the poetic and the mythic image at once reveal and conceal,” Allan Watts claims in his book, The Two Hands of God. Dualities, he explains, “illustrate the inner unity of opposites.” Watts acknowledges the power of the image and the power of the poem to both conceal and reveal, as opposed to logical, prosaic language. Watts knew that such a discussion couldn’t fully be explored in the confines of normal language. He needed images that functioned like poetry.

Poetry comics deal in (to use a comics term) “closure,” which is, the “phenomenon of observing the parts but perceiving the whole” (Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics, pg. 63). The reader makes up the missing pieces themselves, and the artist trusting the reader to comprehend and create meaning between two outwardly disparate ideas, or in the case of comics, panels. Think of a picture of a clock sitting on a bedside table. Then the next panel a smashed clock on the floor. We can, in our minds, create the action of waking up to an alarm and smashing it in that small white “gutter” between panels. We can place a human into the picture. A scenario of emotion. But this is a simplistic version of the power of closure. And this is an instance of image at work. Poetry functions in much the same way, through language. In poetry this is called Negative Capability.

Keats’ famous letter in which he talks about the idea is well known, but always worth looking at again: “At once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason—” This was a moment of acknowledging the massive importance of “closure” in poetry, to focus in on a negative space as being paramount to form. What it seems to do, is access some “truth” without the anxiety of science and logical narrative frameworks. More was left open, free to become. And to be a great poet, you must accept the beauty of “half knowledge”.

The more logical cues the poet removes from the writing, the more unintelligible it is to the learned reader. Most people cannot overcome that barrier. They cannot understand why things that should not be together are together—it is nonsense to them. But it is not nonsense that the poet is after; the poet must find a frequency of knowledge. She must divine access to her core experience and hum it back to the reader with the hope that it gets through. It is the blind feeler, the separate pole that wants to illuminate the absurd contradictions it cannot reconcile, and the unbearable suspicion that we can never fully express ourselves to another person.

Like negative capability, what is taken away, tiny cues in grammar, or perhaps assignment to whom is speaking, to what is speaking—is what makes poetry. “The art of comic is as subtractive an art as it is additive,” Scott McCloud writes in Understanding Comics. “And finding a balance between too much and too little is crucial to comics creators the world over.” We focus mainly on what we add, more than we take away, however. It is often much harder to let go of lines that are ruining a poem—or even a whole poem that is ruining the book—than it is to see that what is absent makes more whole.

The Absurd, Contained

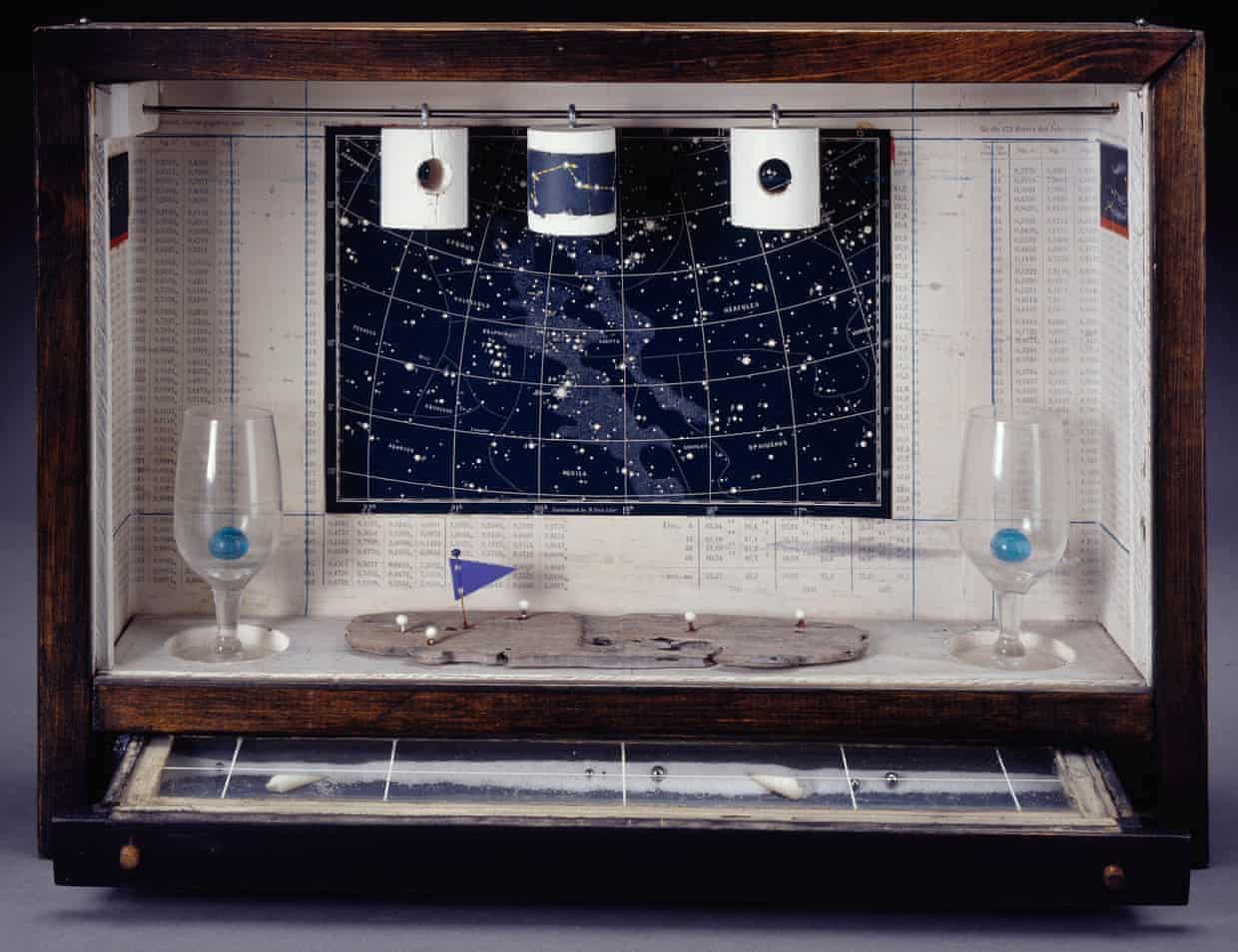

Containment comes in the form of the box, the room of the page, the confine of the panel. The poet will learn this first: that the poem must be contained in white space. You break the line. You make a shape from words using figurative air. Figurative white space. The negative space. All poems—no matter their merit—rely on the negative. The poet learns this first: that the stanza means “room” in Italian. That words are given “rooms” in a house you’re recklessly decorating. It is like Joseph Cornell’s obsessive boxes, his “assemblage art:” boxes filled with items that represent the vastness and movement of butterflies, ballerinas, outer space—all imprisoned in glass-door cases; the clattering together of ephemera in careful, dreamlike 3D collages. It is a containment for the disobedient, the rule-breaking method of communication.

Untitled (Celestial Navigation), 1956-58. Courtesy of Quicksilver/The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/Vaga, NY/Dacs

The poet Ann Lauterbach, in her essay about the great artist Joe Brainard (whose work helped to spark my obsessive interest in image and text), says of Brainard’s choice of favorite things: “He seems to have been drawn to forms of containment, in which the unruly or rupturing experiences of life are brought into the kind of reductive clarity that we often associate with classical modalities.” Poetry comics are defined by their employing of panel, sequence, negative space. They are the gesture at infinitude, enclosed, in what feels almost nostalgic, like a medieval tapestry or litany of images on a cave wall, a tragic, yearning, darkly humorous. It is a caged dance.

The acceptance of uncertainty in your writing is the very acceptance of the instability of language. “I love engaging other senses while you’re reading so that you are brought into the text full-body,” Claudia Rankine said in an interview about her hybrid works of poetry and image. “I love the freedom that is created when the text and the image are in juxtaposition—that it creates a kind of associative field that I can’t control.” The contradictory and conflicting instances of Meaning. As Rankine understands so well, in using image in virtually all her books, she honors the complexity, the shadow absurdity, of human culture. She knows that engaging multiple senses creates an “associative field”—an associative field is multiple concepts joined by some broad idea—and here, milling in a “field,” which is something traditionally bound by fences or stones. We see again the uncontrollable within a containment. “Losing the arrogance of dominion over the poem, to an invisible hand, the poet campaigns for a passage over which the poet has control.” Barbara Guest writes in her poetic statement “Invisible Architecture”: “Yet the unstableness of the poem is important.”

Either way poetry comics are twoness. An entwining.

Poetry, like a compound word, finds its electricity in polarity. “It is by their syllables that words juxtapose in beauty,” Charles Olson says, “by these particles of sound as clearly as by the sense of the words which they compose.” The very phenomenon of juxtaposing syllables, even for the sake of sound alone, creates meaning or Dyad, the basis of creative process, the language of humanity, the partnership of awareness between seeming opposites, such as image and text, sense and nonsense; absurdity and illumination.

But the dyad is also misunderstood. We find ourselves only in anguish. How can we forget so often the opportunities of every moment? Opposing sides need to be acknowledged in order to make music. In my darkest depressions there is a pole opposite of profound understanding. For each incredible joyful occurrence, the horrible opposite looms in the back of my mind, making joy more vivid and incredible. One end of a pair is not the whole picture. Together they make the thing true. In the grip of duality, we see limitation and division. Polarized thinking, we call it.

Poetry Comics deal in their two separate methods of human expression, at once clumsily, at once elegantly. One cannot fathom how they move at all. They are like giraffes. Coming upon them you find that which you don’t understand but also that which resonates. “It’s absurd,” you say. But we are in the kingdom of absurd with poetry and comics. And while some aspect of the neck of the giraffe makes you uncomfortable, it nevertheless infuses you with a sureness in the goodness of the universe. What is absurd, could not be any other way. Albert Camus says in his essay “An Absurd Reasoning,” “the magnitude of the absurdity will be in direct ratio to the distance between the two terms of my comparison. There are absurd marriages, challenges, rancors, silences, wars, and even peace treaties. For of them the absurdity springs from comparison.”

For a poetry comic to be successful, it must convey an uncertainty that stirs something both intelligible and unknown in the reader/viewer, that is, that’s inherently ironic in its perplexing but also entertaining ability to wed mystery with meaning in its art and text.

I Am Troubled by Poetry Comics

I find something deeply unsettling about a word beside an image. Alone, it’s as if it is the first Word ever uttered. Like I shouldn’t be seeing it. Like the planet shat into being at the exact moment a random word was pronounced. A word like “what” or “bun.” And from that, meaning-making was born. It is as if, in some way, poetry comics is an intersection of ignorance and knowledge, sparking awareness.

[line from Barbara Guest’s Invisible Architecture]

I do not warrant poetry comics since I can’t understand or categorize it beyond everything that is already here. And only a handful of examples seem to resonate. Yet, I consider poetry comics, somehow, representative of an essential truth. An unceasing divorce. A problem in front of me at all times. A predicament of the current state of existence. And I’ll admit, as much as Camus might have, to the “conscious dissatisfaction” it implies. In fact, I kind of hate poetry comics.

The part of me baffled by what always seemed like unrelievable limitations around me looks toward the seeming randomness of poetry for relief; in that part of me that looks into the mirror of poetry comics that reflects the unstable design of Being alive and the physical power of the human mind. The imagination in its capacity for language and art desires a kind of translation on the page that holds up to the face of another and asks “You too?” “You?” “You?”

The existentialist might say this question is the curse of meaning-makers. If myths are our way of reflecting ourselves, and relieving an anxiety about why we are in existence, then so too the poem. Maybe when we find a coherent frequency between two opposing poles, we bridge between anxiousness and transcendence. We are for a moment in unity with the contradiction, at home in it.

“Everything that originated from the tree of knowledge carries in it duality,” says the mystical Jewish text, Zohar. To have been awakened into consciousness is to be given the anguish of Two. But with it comes creativity.

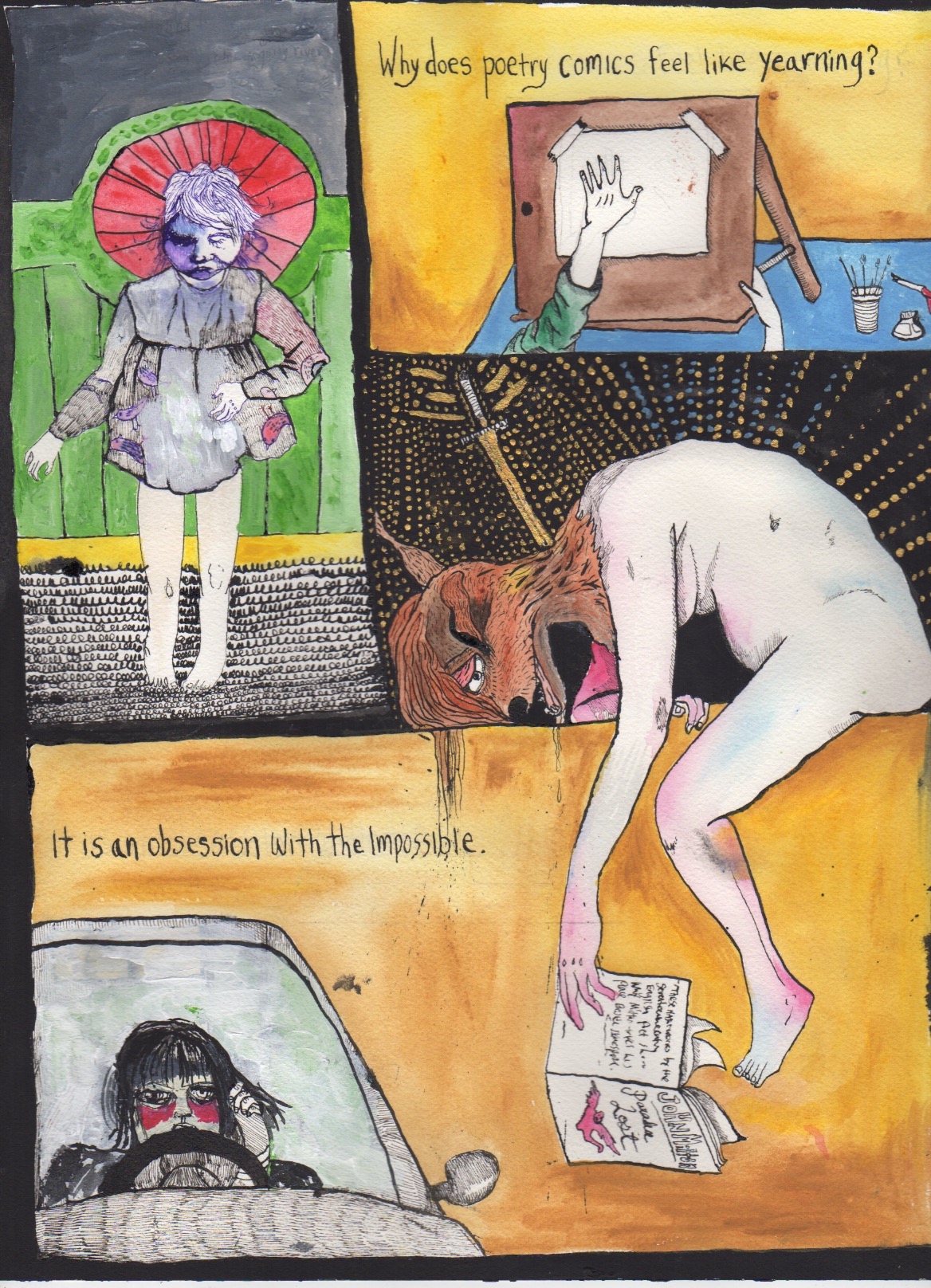

Why does poetry comics feel like longing?

It is an obsession with the impossible. “We turn to God only to obtain the impossible,” Camus wrote in The Myth of Sisyphus, quoting Les Chestov. “As for the possible, men suffice.” Reginald Shepard opined in his essay “Why I Write,” echoing his teacher Alvin Feinman’s view of poetry “as always close to the impossible.”

The results of poetry comics are always failures. But arguably so is all art. We expect God in our art. We expect new, emotional answers. But our art can only ever gesture. It is longing, tragic. It can’t be anything but our own voice echoing back at us. Even when the voice in art comes back unfamiliar and breathtaking, (the ultimate goal of any artist) we are also unsettled by it. When I come upon something that seems entirely in tune with genius, I sit in awe—then anxiously start searching for its flaws. If I can’t find something in the art itself, I move on to the artist, then to the context, then to culture, then to Nature itself.

Perhaps poetry comics are a metaphor for an anxiety of disconnectedness from Nature itself. The philosopher William Barrett said that “man has come to feel himself an outsider even within his own human society. He is terribly alienated: a stranger to God, to nature, and to the gigantic social apparatus that supplies his material wants.” This separateness from nature must in fact, be an insidious artifice, one based on our insufficient complexity of thought: how could we possibly be separate from that which we are? And yet, the separateness is there, an undeniable chasm. This chasm, this gutter.

Psychotherapist James Barnes writes in his essay, “How the Dualism of Descartes Ruined Our Mental Health,” that we need to consider “mental disorder on a metaphysical level, and not just within the confines of the status quo.”

“In the face of an indifferent and unresponsive world that

neglects to render our experience meaningful outside of our own

minds – for nature-as-mechanism is powerless to do this – our

minds have been left fixated on empty representations of a

world that was once its source and being. All we have, if we are

lucky to have them, are therapists and parents who try to take on

what is, in reality, and given the magnitude of the loss, an

impossible task.”

This claim redounds on poetry and art profoundly. Writing poetry and poetry comics comes to facing my confusion over duality and my anxiety over separateness, specifically what they mean exactly. The truth of the matter is that there is separateness in everything, and yet it is not what we think it is, because we have denied ourselves ways of talking about it. Our idea of Meaning, is one based in logical, scientific, Cartesian analysis. Poetry is one of the most powerful tools for exploring absurd and logic-defying concepts, or what Allan Watts called “the inner unity of opposites.”

Poetry comic are near impossible to draw and write. The act of putting poetry and images together deserves reflection partly because of the intense difficulty—the rarity—of making image and text function together as one effectively. What is it exactly that makes it effective? Certainly there is something that triggers a poetry comic to life, at least some of the time. As for the absurd, Camus observes that “in its distressing nudity, in its light without effulgence, it is elusive. But that very difficulty deserves reflection.”

The friction I struggle with when I am making poetry comics—the subtle shift from something “working” to not-working, the seeming randomness of it all—feels like I am dealing with Camus’ “light without effulgence.” It is a constant frustration and discomfort to make poetry comics. It is a yearning that pervades and defines my whole impetus for drawing and writing: the chaos of it all, the nonsensical nature of trying to convey. It can help to have poems clash with something else, in an attempt to extend their reach, (music, image, texture) to get more out of the task of what? human prayer, desperation to communicate, the longing to join with something? Poetry comics are like letters to the inscrutable universe. The page, with its rectangles and blank space, is the envelope. I have somehow always been cataloging the People of Distress in a state of longing, searching for someone to pick up the little red book and say, “Yes, I see you.” Because of this, I am telling you now, I see you, out there, reading this article and perhaps feeling no closer to poetry comics than when I started, but that doesn’t matter. You made it to the end and I see you, little person of distress, I have you now in my book. I’m carrying you around. “The cosmos is seen as a multi-dimensional network of crystals, each one containing the reflection of all the others, and the reflection of the others in those reflections…” Alan Watts says. I like to think this, therefore: that in the center of each of these reflections a single word shines. A word that means everything reflected back, in a constant absurdity of other and self. All the People of Distress that want to be recorded are already put down on that cosmic, black inked paper, waiting to be read.

So, make something uncertain today.