Writing Internationally: Ian Haight in conversation with Tzveta Sofronieva

Tzveta Sofronieva is the author of over twenty books, including Multiverse (2020), a collection of new and selected poems written originally in German, Bulgarian, and English. Ian Haight, author of the collection of poetry Celadon (2017), is also the co-translator, with T’ae-yong Hŏ, of Spring Mountain: Complete Poems of Nansŏrhŏn and Homage to Green Tea by the Korean monk Ch’oŭi, both forthcoming from White Pine Press. Excerpts from Homage to Green Tea are included in this feature, along with new work by Sofronieva.

Haight: Tzveta, you live and work in Europe. How do you make and maintain connections with an American writing community?

Sofronieva: Reading books from the U.S., corresponding with American authors, supporting their works in Europe… Also, literary festivals and residences, like the IWP Iowa where I was last fall, play a big role because they allow for the cultivation and creation of common projects. Translators connect me with other poets, like Michael Heim did. A big impact on my knowledge of contemporary American poetry and my connections with poets in the U.S. has been my American publisher and himself a poet, Dennis Maloney, who keeps me apprised of intriguing new voices, sends me books from his press, and recommends books from other publishing houses. Magazines and online journals also keep me in step. Social media is less important for me; I rarely discover a new voice there. Books and personal meetings and letters remain my preference. In Berlin there are several English bookstores, and a huge international community of authors; quite a number of American poets live or spend a lot of time in Berlin.

Haight: Your collection Multiverse is an international text in several ways. How did working with the editor, Jennifer Kwon Dobbs, contribute to the internationality of the book?

Sofronieva: Dennis Maloney, fully aware of the complexity of the project, proposed that we have an editor for the book. The choice of Jennifer Kwon Dobbs came naturally–she is an author with the same press, and her work as an academic and as a poet is situated between English, Korean, and German. The press was interested in a chronological sequence, and we partly kept this, but Jennifer strongly supported my wish not to stick too much to it. She carefully discussed with me some details in the poems to be sure I intended certain unusual language usages or helped me determine if I might need to change it for the American reader. For me this is the main feature of a good editor: giving you the glance from aside and at the same time the full freedom to be the maximum of yourself in a book.

Haight: In your poetic reflection “Writing the Multiverse” in Code Switching in Arts and in several discussions about international literary projects, you describe discrimination on the basis of language, and in doing so, you introduce the word “tongueism.” Could you talk a little about this word?

Sofronieva: Like race, nationality, origin, gender, social status, age, professional occupation and more, language serves as grounds for open or, very often, subtle but undeniable discrimination. I use the word tongueism because we need to differentiate between a discrimination of a literary text within a literary multilingualism framing, and a discrimination of a person/an author based on language, the later called linguicism. Editors continue to read a text differently when it is created in an adopted language. Each time when we face literary multilingualism, we need to look for the emergence of a poetic innovation and the strategy towards an addition of an aesthetic feature. Pre-assuming linguistic insufficiency of a text created in an adopted language is an act of tongueism.

There is also a hidden tongueism behind a cultural representation narrative—discussions are often not about the text as a literary work but as an element of something else. In Germany we have fought against the misuse of prizes and projects that seem to be noble and supportive but in fact humiliate the work of the writers who adopted German as a literary language. It is strange for me to hear about books described as so African American, Latino American, Native American, and how the conversation about them is moved completely to an out-of-literature space. This is needed at times for social reasons but how it is done is of great importance. Often the literary quality is discussed in a way that makes debatable if the text would be in the conversation if not for the label. The innovative literary strategies coming from the riches of the trans- and polylingual writing (no matter if in a mono- or multilingual text) are mostly taken out of the focus. Labeling is for me an act of tongueism.

Editing and translating are not only literary but also political acts.

Haight: The title Multiverse is a word that came to you from quantum mechanics. What are your thoughts on the relationship(s) between poetry and the natural sciences?

Sofronieva: Multiverse stands at the core of my poetic work and, in my view, is a powerful concept for the analysis of multilingualism in literature. It mirrors the diversity and the sheer number of possibilities of verses in poems. It implies the difference in the literary strategy and the many paths toward understanding ourselves, the riches of our abilities to impart and inspire. It expresses the complexity and multiplicity of the Anthropocene aesthetics. I proposed for the understanding of literary multilingualism the term otherverse for texts that are written as multiple originals. The analysis is then distinct from the use of clones and parallel realities in science fiction and of alterverses in gaming or alternate universes in cosmology, so that we can work holistically and not slip into relativist attitudes. But most of all I suggest this term to stress the otherness more than the similarity or the alternation. And yes, this idea comes to me naturally from Physics. Poetry, learning poems by heart, was part of my childhood and primary school, long before my education in science. But scientific thinking and knowledge are present all the time in poetry. Remember Lucretius’ “De rerum natura” (“On the Nature of Things”). Listen to the lyrics of the English lullaby “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” from the early 19th century English poem by Jane Taylor “The Star.” To me, poetry becomes richer and deeper when it incorporates more knowledge. And this is even more so when we see how structures of thinking and invention in poetry and in science often go hand in hand.

In science we deal all the time with movement. In principle we cannot observe objects; we can observe only interaction between objects. Poetry is also ruled by interactions: between words, between word, sound and meaning, and more. Both science and poetry are in search of language; they name things, enlarge, and create language realms. One of the challenges for us is to accept a legacy of experiences of others without rejecting or abandoning our own experience. I prefer to intertwine poetry and knowledge in a subtle way. I like to find a poetic way to express complex and condensed scientific knowledge. The stars shiver because of the air we need to breathe to be alive; and we find the stars beautiful because they sparkle. In the deceit that they twinkle are complementarily combined the wonder of the air/breath and the wonder of the stars/cosmos. This is pure poetry to me. Curiosity is the magical word that brings us into movement. And movement is the magical condition when we feel alive.

Haight: You’ve worked a long time in translation and helped with the editing and publication of American books of poetry in Europe. Have you observed anything unexpected in the process of editing and translating for publication in the United States?

Sofronieva: I was surprised that being a poet in the U.S. is seen as an academic career. To be a poet has always been for me simply a way of existing, and I shared this view with many poets in the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s. I was astonished how much creative writing had moved to academic circles. I guess in Europe we have more possibilities to remain independent freelance authors. I also felt the struggle with the danger of tongueism in times when English becomes more and more the possession of an international body of writers who are not native speakers. I have experienced tongueism in Germany and there I had expected it somehow as one expects it in Great Britain and in France or Russia—all these old still-suffering-their-historical-fixation-on-dichotomies cultures. But North America, both the States and Canada, was in my experience different. In the 90s, great American poets would not question my poet’s right to a certain image in English. The situation has improved in Germany while in the U.S. there seem to be a kind of “America first” attitude in the literary field, too. But perhaps these thoughts come from a higher sensibility based on non-literary developments that make me worry about the future…

Haight: You have a cycle of poems called “More Future.” The cycle offers a variety of futures to consider, and one of the poems was included in the AGNI issue on the possible futures of translation. You’ve also spoken about a kind of “future perfect” during your recent residency at the University of Iowa. What are your main concerns about the future?

Sofronieva: The problem with the future is that it comes very quickly, as Einstein joked. Dictionaries define the word future as the time that is to come, but also—in its original use from the 14th century—as the time after death. It seems that future has something to do with the fear of death; and that it is constantly there, continuously happening—each moment we speak we have already entered it many times. In Iowa I talked of a future perfect because a lot of dangers seem already irreversible. Nowadays, many of us fear for life on Earth, not only for our lives as individuals. We have shaped our world into a form irreversibly damaged, and we have a word for this: Anthropocene. Within the limited space of our irreplaceable planet, while resources dwindle amidst a growing thirst for their possession and the ruthless struggle to redistribute them, in conjunction with crises in climate and energy sources, in a time of misunderstandings and drifting-apart paradigms and languages, rampant nationalism, constant wars, and loss of democratic elements, as we turn the planet into a garbage dump and establish money as the only measure of life—as if people eat money, sleep on money, pee money etc., humanity seems to suffer from the neurotic anxiety of a hyperactive, unaware, and unrestrained teenager. In our hyper-performative age, image displaces reality, and indifference grows in tandem to a thirst for performance and self-staging, for the medialization of everything that happens to the point of a total neutralization of meaning. Fear seems to have taken over to such an extent that we have begun to ignore it.

The reading of the past and the present depends on visions of the future. The past is a graphic with different parameters which we must and can analyze and depart from together. It is not the system of the future. We do write anew old cultural narratives now, and bring unheard voices into sound, precisely because we want a future of fairness and respect. We increasingly feel the lifesaving need for multilingual senses and emotion knowledge. There are no perfect times, and we learn to live in the irreversible state of the hatreds and catastrophes we have already created. But we could perhaps still decide that an acceptable future is possible and shape the present accordingly—or am I a modernist and a dreamer?

Haight: Deutschlandradio called you a poet involved in a tender search for the aesthetics of the Anthropocene. How would you describe the aesthetics of our time as they may relate to a possible future for poetry?

Sofronieva: Hybrid, multilingual, trans medial, protean, with an honest approach towards technology and cultural representation. The human craving for performance, our need for a stage, all our social conflicts which emerge from the despair that is inherent in the loss of life-sustaining conditions—these cry out for comfort, for narration, for imagination, for artistic skill, and for analytical insight and constructive criticism. Poetry can reflect the danger we inflict upon ourselves, the exponential increase of this danger, its anonymity, and the indifference that blurs it. We finally, as Erwin Schrödinger was asking for hundred years ago, get a chance to distinguish between a sharp photo of clouds and a picture that shows something foggy not because of the weather, but because the photo itself is out of focus.

Haight: Could you talk about your next project? What are you working on now?

Sofronieva: I have just finished texts for and about the theater, two of which are currently performed by the Emergency Theater in Sofia. Now I’m working on a new collection of poems in German. I’m also preparing my next book of poetry in English which will include mainly translations from German but also a cycle of new poems written in English while I was in Iowa, and new self-translations of some older Bulgarian poems that are related to the topic of the new book. Literary multilingualism can be well compared with the multiverse in Physics as I discuss it in “Writing the Multiverse,” and it enables me to integrate the time dimension in a productive manner, and several space dimensions zooming in and out. The text we call a self-translation is in fact an otherverse. I am happy that some of these poems are features in this issue of Plume.

Poems by Tzveta Sofronieva

Author’s translations from the Bulgarian

Fleur

I lived in a glass house but when I grew taller

my father rose and broke the ceiling—

and from his wounded hand dew fell on me.

My mother’s tears soaked into my roots

and hidden legends poured into me.

I live now in a world so much unlike the former,

with fresh air and true light, with different voices.

When I see a false sky I break it by myself.

I can recognize the cuckoo’s syllables,

and spell the words of the songbirds.

Цвета

Живеех в остъклена къща, но стигнах ли високо

баща ми се надигна, разчупи тавана –

от порязаната му ръка падна първата роса върху ми.

Сълзите на мама по корените ми попиха

и преливат у мене премълчани предания.

Цъфтя сега в свят, различен от предишния –

и въздухът е друг, и другояче пеят птиците.

В тичинките си пазя любов.

Като срещна лъжовно небе, сама го чупя.

Разпознавам гласа на птиците от кукувичите срички.

From the poetry collection: Sofronieva, Tzveta, Зачеваща памет (Conceiving Memory), © 1994, Edition Avantgarde, Издателство Прозорец, Sofia.

Meteora

The colors of the sea flow over the mountains.

In Kalambaka, miles inland from the coast,

the monks were lifted with ropes and nets

over the crags of a petrified sea.

That is a fairy-tale place–Meteora!

The Aegean is caught up in the dryness here.

Far away from the overcrowded cities

the monasteries float, vigilant,

over the towering columns of the pinnacles.

We are not sure about the name of the settlement,

all we know it is full of stories. Let’s set off.

Метеора (Каламбака)

Там рибите преливат в музика от цветове…

В Каламбака, на мили от брега,

монасите ги вдигали във въжени торби

над зъберите от предишни риби.

Това е чудно място – Каламбака!

Егейското море е вързано на сухо тука.

Далеч от всички мъдри и големи градове

манастирите стърчат на куц крак

върху дивите зъби на планината.

Не сме сигурни за името на селището –

неясна е последната съгласна.

Ала е в Гърция. Да тръгваме.

From the poetry collection: Sofronieva, Tzveta, Зачеваща памет (Conceiving Memory), © 1994, Edition Avantgarde, Издателство Прозорец, Sofia.

Attention Difference Syndrome

Skin embraces skin, senses embrace the senses.

He deals with cells, he answers to the question

whether patients or research fill his days.

And I miss opportunities and planes, loose pens

and friends, transform the losing

into an art. I join in the hyperactivity of the day.

Touching requires a different organization of the brain

as, for example, writing. This makes us sensitive and matchless.

Does this sensation match?

Attention Different синдром

Обвива кожата кожа, сетивото сетиво.

Аз се занимавам с клетки, отговори той на въпроса,

пациенти или изследвания изпълват дните му сега.

А аз изгубвам, превръщам губенето на химикалки

и самолети, на сходни хора и предмети, на отдадености

в изкуство от върховен ранг. Вписвам се в синдрома на деня.

Погалването изисквало по-друга организация на мозъка

от, например, писането. Това ни правело различни хора.

И не забравяме ли приликата?

From the poetry collection Sofronieva, Tzveta. Разпознавания. (Discernmennts /Recongnitions) Издателство Жанет 45, Plovdiv, 2006

Author’s translations from the German:

We are

ten miles upward, a breath can’t find oxygen

ten miles under us rage six hundred degrees

in Fahrenheit, or it would be another number

different units don’t change our universe much

we are ourselves verses of a discernment

caught in our own wholly imaginary nets

sharp feelings next to gentle senses

a search for breadth is like drawing breath

a volcano pins flying machines to the ground

what do birds set their minds to in an ash cloud?

we carry a lot of fears, mostly because of confusion

yet poetry, if we believe Pushkin, ought to be a bit silly and dense

wir

zehn kilometer nach oben ist jeder atem verflogen

zehn unter uns toben sich fünftausend grad aus

nach celsius gemeint, sonst wären es andere zahlen

unterschiedliche einheiten ändern kaum unser all

wir selbst sind kleine gedichte einer wahrnehmung

gefangen nur in den eigenen frei erfundenen netzen

scharfes empfinden hand in hand mit sanftem spüren

weite suchen gleich eine sicht weite haben

eis vulkane halten fliegende cyborgs am boden

wofür entscheiden sich bei aschewolken die vögel?

viele ängste besitzen wir, vor allem vor verwirrung

aber poesie soll nach puschkin ein wenig dumm sein

first published in Wortball, Hausacher LeseLenz, © 2010 Tzveta Sofronieva

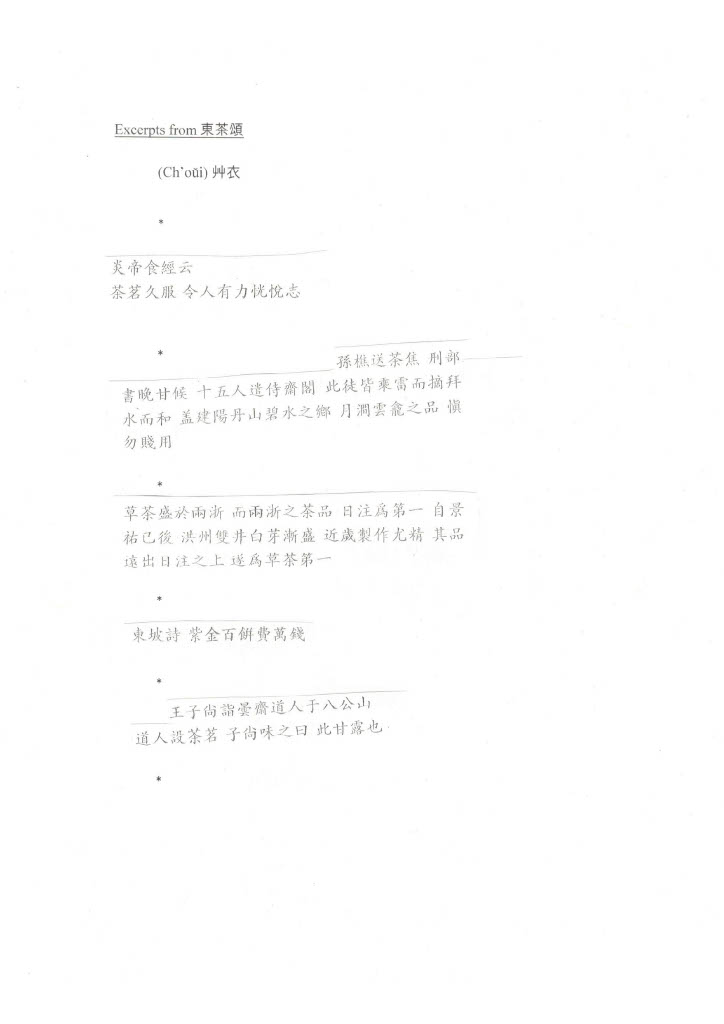

Excerpts from Homage to Green Tea

By Ch’oŭi, translated by Ian Haight and T’ae-yong Hŏ

Always drinking tea gives man strength and a pleasant heart.

—from The Book of Food by Shennong

*

In the essay, “Sending Tea to the Minister of Justice” by Sun Qiao,

we find these words: “I’ve sent fifteen packages of green tea with a

lingering flavor to be offered at a shrine. The leaves were picked

during The Season of Thunder, so be mindful of water for the tea’s

harmony.”

Generally, the land of this tea—the red mountain in Jianyang County—has pure water. Moonlight on Mountain Streams and House of the Clouds are quality teas from that land; one should not use these teas carelessly.

*

Zhejiang Province in China produces leaf tea, and the quality of Infusion of Sun is prized. Since the Jingyou Era, Two Springs and White Sprout teas from China have grown in popularity; lately, agricultural knowledge has increased, so the quality has improved. Their quality is much more than Infusion of Sun—hence, the tea leaves have become known as most precious.

*

One hundred cakes

of golden-purple tea

cost ten-thousand coins.

—from a poem by Dongpo, untitled

*

King Zishang visited a priest from Tanji. On Eight Proverbs Mountain, the priest shared tea with the King. After drinking the tea, King Zishang exclaimed, “This is heaven’s sweet dew.”

photo cred: Heike Steinweg

Tzveta Sofronieva / Цвета Софрониева, a physicist and historian of science by training, is the author of over twenty books, including Multiverse (2020), a collection of new and selected poems written originally in German, Bulgarian and English and A Hand Full of Water (2012), translated from the German, the recipient of a 2009 PEN/Heim Translation Fund grant and the 2012 Cliff Becker Book Prize in Translation. Her poetry has been translated into twenty-one languages. She was awarded the 2009 Adelbert-von-Chamisso-Förderpreis for her poetry written in German and a Bulgarian Ministry of Culture Award for her contribution to the Bulgarian literature (2020). Her play “The Value of a Human” based on her book Anthroposcene (2017) is currently performed in Sofia with the support by Bulgaria’s National Cultural Fund. She was 2023 IWP Writer in residence in Iowa.

Ch’oŭi (1786-1866) was a Korean Buddhist monk given a traditional Confucian education, making him a uniquely trained scholar of his period. Ch’oŭi is considered one of the first pre-eminent experts on the subject of green tea in Korea.

T’ae-yong Hŏ has been awarded translation grants from the Daesan Foundation and Korea Literature Translation Institute. With Ian Haight, he is the co-translator of Borderland Roads: Selected Poems of Kyun Hŏ—finalist for KLTI’s Grand Prix Prize—and Magnolia and Lotus: Selected Poems of Hyesim—finalist for ALTA’s Stryk Prize. Working from the original classical Korean, T’ae-yong’s translations of Korean poetry have appeared in Agni, New Orleans Review, and Prairie Schooner.