A Window Into That In-Between Place That Has No Name

A Conversation with Elaine Sexton

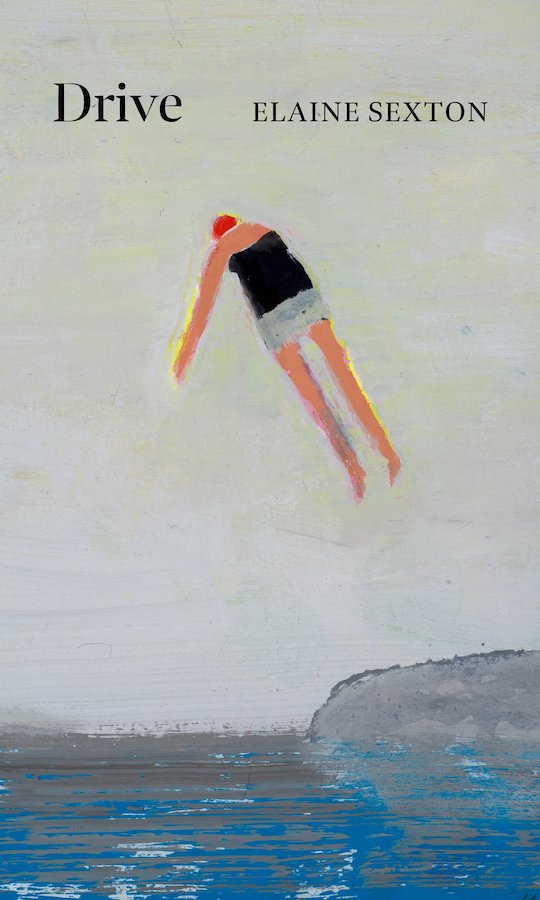

There is much to admire in Elaine Sexton’s new collection, Drive: her reverence for place, not just for the country (such as a small town in New Hampshire, a block away from the ocean) or for the city (mainly NYC), but for the liminal, the in-between places when she is traveling, neither here nor there, but in a space all to herself, where anything can happen, any memory can arise, anything can be retrieved or released. Though much of Sexton’s work is rooted in family, relationships, loss and the making of art and legacy (as when her mother passes down the art of sewing, which in Sexton’s world becomes the small books she sews together for her unfinished poems, and carries with her in her pocket), her work is also rooted in the places themselves, her connections to particular landscapes, streets, bodies of water— paradoxically deepened and accentuated by the very transit that takes her toward and away from them.

In the following conversation we explore Sexton’s new book, her beginnings as a writer, her creative life, and how her time between places invigorates her work.

*

Frances Richey: Congratulations on your new book, Drive. Where did the impetus for this book come from and how did you arrive at the title?

Elaine Sexton: The title poem for this book actually came from my previous book, the last poem I included in Prospect/Refuge. At that time I was spending a lot of time in the car, and making frequent road trips to and from New York City, where I live, to New Hampshire, where I grew up. My brother was gravely ill. Even at that time I started to think of this idea of transportation, of the body as a kind of vehicle, as the beginning of something. So, going forward, these ideas around the car were just beginning to take shape. That poem, and the poems in this new collection are about that in-between place, where we are when we are traveling, really a third place, of that time and space when you’re not really anywhere that has a name.

FR: The book does capture all the different aspects of the word, drive. As I was reading the book it seemed that the title was right for every poem, the title being the umbrella for all those poems. Did the title come first or did the poems come first?

ES: Well, as I said, the title poem was there in my last book, but I had just skimmed the surface of drive as a subject. I spend so much time in cars, trains, and various modes of public and private transportation, I kept coming back to that word, even though I didn’t consciously start out with the idea for the poems I wrote after it to be under the umbrella of Drive.

FR: It’s like using the last line of a stanza for the first line of the next stanza, or the last line of a poem for the first line of the next poem…

ES: Like in a crown of sonnets.

FR: Yes! Maybe you’re going to write a crown of books…

ES: Now that you say this, in some ways my four books are organically linked by transportation and locale. The cover of my first book, (Sleuth) is an altered photograph of my brother and me as children standing in front of an old Oldsmobile in front of a beach cottage belonging to my aunt, so the car as an object of metaphor was embedded in the title poem. My second book Causeway, also references transportation, as a road between two bodies of water, or thought.

I never consciously thought of my books as linked in this way, until now, but I do think of books, themselves, as vessels, containers for what possibly transports us.

FR: Stanley Kunitz believed that writers/poets have a handful of key images that show up over and over again in their work. I’m wondering if you have a sense of your own key images. For instance, I think one of your key images is the sleuth. Even in the poem in Drive where you were talking about the geese and you said something about, “are they tame?/No, I think they’re curious.” I don’t have the page open, but that was an image, and an observation that stuck with me. Going back to Sleuth, your first book, it’s always that sense of trying to find what’s hiding underneath the surface, trying to put the pieces of a puzzle together to figure out whatever the puzzle is in that particular book. That seems to me one of your themes. Do you have any others?

ES: To stay with the sleuth for a moment, that’s so observant. Curiosity as a climate is one, for sure, searching for what’s under the surface of things. In Sleuth I thought, loosely, of the poet as private investigator, looking at things not being what they appear. I always find this a source of delight or intrigue, when some- thing or someone surprises me, being other than what you expect. I’m thinking of “the mugger who looks like a parish priest,” and the woman “who is rich but looks poor” boarding a bus in “Public Transportation,” a poem from that first book. But back to your question about key images, or ideas. In terms of physical subject matter, I grew up in a small town in New Hampshire a block away from the ocean, and live in New York, so that kind of seascape or landscape, and the movement between the small town and the city are subjects and tensions I often return to.

I was just listening to a talk that Diane Seuss gave on Theodore Roethke, and, in particular, on personal landscapes, how Roethke drew so much from the acres and acres of greenhouses, which were his father’s business. And that she drew from impressions that began in settings like that of her grandfather’s barbershop. I developed a deep appreciation of the natural world from my mother, who grew up in Pittsburgh, at a time when the air was toxic, and smoke from the steel mills was so thick you couldn’t see the sun. As a child, by her side, I absorbed her relief in simply breathing, and felt lucky to have the sea. Through her I learned an acute way of observing things, material things, sewing and making, and a way of weaving the past, her past, and the present, her present, together.

FR: It’s funny you mention the sewing. I was thinking as you were talking that you are not only a writer of books, you are a maker of books, a sewer of spines of books. One of my favorite poems is “Sew,” about your mother. There’s something beautiful about the continuation or passing down of the art, even though it’s used with different materials. The thread is always there.

ES: This sewing theme also dates back to my first book, and one early poem, “Sewing a Sonnet,” about my mother and learning to thread a needle. So, again, sewing is another link between books.

Part of my writing, or really revising process, is in physically handling the text. I cut up my poems and sew or fold them into palm-size books. Emily Dickinson, of course, called these fascicles. My version of the fascicle is this simply-made book of a single poem I carry around with me for days and days and weeks while working on it. Making a poem this portable, I can always pull it out of my pocket and revise and refine it.

FR: So sewing is one of your key images.

ES: Yes.

FR: When I was thinking about your work as an artist, I was thinking about your collages, and how poems can be something like collages in their making. Would you talk about that?

ES: Yes. I think poems are very much like collage — setting disparate things side by side, like memory and experience, in unexpected ways. I believe poetry and collage are twin arts.

FR: You’re an art critic, you’re a lover of the visual arts, you write reviews, you make books, you write books, you collage. Is there a rhythm between the writing of your poems and moving from that to collaging, or reviewing, or going to museums for pleasure?

ES: You know, when I read a book to review it, or look at an exhibit or artwork as a critic, I focus on how it is made and finding a way to explain it or describe it, to put it in the context of other books or other works of art. When I’m looking at art and literature for pleasure, I’m also looking at it as a maker, what I can glean and learn from it.

I’m a teacher, so I am also hunting for things to use in class. They’re all of a piece: the learning, the making, the process. I sit up the moment I hear about makers, writers and artists, talking about their process. Even though we are all so different, we are often so much alike.

FR: How are we alike?

ES: We’re all a little OCD, a little obsessed. Don’t you think? We are always working. I think in words. I’m writing, even while experiencing almost everything. So as makers my guess is we are all completely preoccupied with the thing we are doing wherever we are, whatever we are doing.

FR: It’s interesting to me to see how different artists and writers manage their time or don’t manage their time. Chaos works for some people.

ES: I do have something to say about time management. While writing my first three books I had a day job as a magazine publisher. Eight to ten hours a day, my base of operations was an office. I did everything from there. My work for hire, and also the business side of poetry. Without that kind of confinement, it is hard to stay home, not to spend all my free time looking at art! I think of Frank O’Hara and his time management with his Lunch Poems.

FR: It certainly is a different animal. I had a day job for twenty years, and I couldn’t do any writing. It was so all-consuming. Was it hard, when you had your day job, to get your creative work done?

ES: The poems I wrote in those years were shorter, more compressed. I wrote one of the longest poems I’ve ever written, which is “Transport,” after that time. This appears in Drive. I prefer to read shorter poems. So when I write long poems I worry how patient readers will be with, say, a five-page poem.

FR: If it’s a good long poem, I think you can hold a reader. “My Mother Would Be a Falconress” by Robert Duncan comes to mind. It’s a long poem and I feel mesmerized every time I read it. Galway Kinnel’s poem, “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ Into the New World” is in fourteen parts, and I love reading that one too, out loud. I get chill bumps even thinking about that poem. And there’s Homer, of course…

I marked several places in your poem, “Transport.”

…There is an end

to a wave. That’s my view,

my range, those are my thoughts

as they downshift from the sky

to road to sea in a Fiat

which struggles to power

its way into Spain

over the steep pitch…

And further down into the poem:

skirting sharp curves,

as I become the sea

become the horizon.

Driving alone

voices in my head

wait to be heard,

those dying to speak,

enter the car…

I made a note when I got to this stanza: “Do you believe in ghosts?”

Do you?

ES: No. I don’t. The closest thing I can think of to a ghost is conjuring up the presence of my father, who died when I was three. So the reality of life and death came early. But I wouldn’t actually call it a ghost. Ghosts…the conscious brain knows they’re not there.

FR: Donna Tartt has a quote about ghosts in The Secret History:

“There are such things as ghosts. People everywhere have always known that. And we believe in them every bit as much as Homer did. Only now, we call them by different names. Memory. The unconscious.”

ES: Oh, I love that.

FR: There are two poems facing each other in the book. I’d read the first one before, “Sky Burial,” and thought it was about your mother. But then, the second one, ”My Dead” is clearly about your brother, and I wondered if they were both about your brother.

ES: “Sky Burial” refers to a very close friend, thoughts I had while wearing one of his shirts. He died, and very shortly thereafter my brother died, and they were both in their early sixties, so they live in the book side by side. I think it’s okay not to know who “Sky Burial” is about, but it is dedicated to him in the end of the book.

FR: You’re right. Your audience doesn’t need to know who every poem is about. I thought “Sky Burial” was about your mother but you could overlay that poem over any loss. It could be my father. They’re both beautiful poems:

My Dead

brother returns as

the old man in the sea

surfing. The waves change,

but always change

in the same way. My brother

will always be a comma

in a sea of commas,

a pause in the loose

language of waves…

When did your brother pass?

ES: My brother John died in 2015, and my friend Tom, in 2014. To your point, I can see how my brother may seem to be a kind of ghost, a ghostly presence. The comma. When you look at surfers they look like tiny commas out there on the waves.

FR: Do you have any rituals? Favorite pen, special paper? Can you only write in certain places?

ES: I do have a few rituals. I’ve never been able to keep a diary. But I keep a kind of commonplace book, notes and quotes and articles, things I want to remember and go back to. I have been making those one-page books I mentioned earlier, for over a decade. I cut up poems and paste them into these books, and it’s a kind of ritual. But I also make collages in this form as well.

Another daily ritual, that started during the pandemic, is list making. I’ve been sharing seven observations a day every day, every morning with another writer for over a year. These lists form a kind of skeleton, that often turns into the backbone of a poem. I find partnering with a trusted reader, and sharing work with peers is key. There’s something about having someone out there who’s waiting to hear from you, that keeps a ritual, like the list making, alive.

FR: Your life has changed a lot in the last couple of years. You got married.

ES: I don’t think anything substantive has changed, honestly, but yes, a year into the pandemic I got married. My partner Nora and I went to the town clerk out on the east end of Long Island, where we hunkered down that first year. Physical offices were still closed to the public. We went to a drive-up window. It felt like ordering a hamburger or something. We pushed the little piece of paper under the window… This all happened three days before this new book was accepted. So nothing changed, but a lot happened!

FR: With everything from Covid to the Supreme Court decision about Roe V Wade, there’s so much going on politically all the time. You don’t get into flat-out political poetry, but do you sense that these things going on around us are somewhere underneath the things you’re writing about?

ES: Yes. Of course. “On Rothko’s Dark Palette,” refers to the day the election was called in 2016. Several poems speak to what it is to be a woman in our culture today, “One Sings, the Other Doesn’t.” Others are about racism in the workplace, gun culture. A poem, “Ride,” that’s ostensibly about riding in a convertible, is really about decency, ending with the line: And decency is blind, unseen, until/ it isn’t.

FR: You know there’s this thing where you’re in the middle of something, like you’re in the shower or in the middle of a telephone conversation or a meeting, something where it’s hard to break away, and all you want to do is pull out your pen and paper as a line starts coming—have you ever had that moment where you just have to excuse yourself so you can get the line down?

ES: Yes, definitely. Again, I’m always relieved to have a fascicle in my pocket. Some phrase will come and I have a place to write it down. I’m not always unhappy when I get stuck in traffic, and I have a poem or home for a poem in my pocket.

FR: I love to ask this question of writers, so bear with me because it takes a minute. There was a science fiction movie in the 1960’s from a book by H. G. Wells, called The Time Machine. A Victorian English inventor travels far into the future and finds that civilization no longer exists. The inventor realizes he can help these lost future people create a new civilization. So he goes back to his time, takes three books from his library, and leaves for good to help create a new world. His housekeeper notices there are three books missing and she muses about which ones he would have taken. If you were that inventor, going far into the future to help create a new, humane civilization, which three books would you take?

ES: My mind goes straight to the poems of Emily Dickinson, and Whitman’s, Leaves of Grass. They’re timeless. The other that comes to mind when I think of civilization is a rich English language dictionary. People forget that dictionaries are authored. I love the reminder, noting the little tiny initials next to the definitions in the OED (Oxford English Dictionary.)

FR: Just one more question. I can’t believe I almost forgot to ask you this one. When did you start writing poetry?

ES: In high school.

FR: What got you started?

ES: I distinctly remember the first time I was singled out in a classroom for something I wrote. I was a sophomore. Something I wrote that was supposed to be a brief essay was really a poem. I did something in that piece without knowing what I was doing, and it was singled out for praise in class.

FR: Do you remember what that first poem was about?

ES: I don’t. All I remember is there was something incantatory about it. It was kind of song-like. It was the first time that I thought, oh, something that I wrote, made, created from scratch, could make an impression. After that, I was a closet poet for the next twenty, thirty years. I wrote and wrote and almost never showed my work to anyone. It took a long time for me to come out as a poet.

Elaine Sexton is a poet, critic, educator, and maker. Her most recent collection of poetry is Drive (Grid Books, 2022). Her poems, reviews, and essays have appeared widely in journals and online including American Poetry Review, Art in America, Five Points, O! the Oprah Magazine, Pleiades, Poetry, and Poetry Daily. She teaches poetry at the Sarah Lawrence College Writing Institute, and has been guest faculty at numerous colleges and writing and art programs in the U.S. and abroad, including New York University, Poets House, and Arts Workshop International (Assisi, Italy). A micro-publisher, her visual artwork has been exhibited and featured in print and online. Her iPhone photos have been exhibited at Carriage Trade, the lower east side (NY) gallery, will be, again, in “Society Photography X,” in 2023. elainesexton.org