Bruce Weigl

What it Means to Lose a Teacher Under Quarantine

“Write it down, just like you told me.”

SF

All of us are gathered here to celebrate the work and the life of our teacher, friend, and master of the arts of poetry and translation, Stuart Friebert. It is not ironic that what we have to offer him, now that he’s gone, are words, but they are words nurtured into deep meaning, and chosen with the precise care of the diamond cutter, because that’s what he taught us all to strive for: to nurture the words that you’ve chosen with great care. That was at the heart of his teaching and it remains clearly throughout his work in poetry and translation. Although I don’t choose here to write about my relationship with Stuart, that would be selfish and beside the point, I do want to say that I had the good fortune to be his student, and that apprenticeship shaped who I became as a writer and teacher because at his side I learned the most essential things about what poetry is, and why poetry is necessary.

During my undergraduate days at Oberlin, Stuart was most valuable to me as someone who would read my attempts at poetry and show me exactly where I was being insincere. He never hesitated to slash through long sections of my over-written poems, finding some kind of heart beating there, and then teaching me how to build something around that heart. If you know Stuart, then you understand what I’m talking about. If you don’t know him then let me say that he had that rare ability to teach you how to find your own voice, and for a poet, for any writer really, nothing is more important than that. Students of Stuart’s share in common the kind of sheer bravery it took to step down into his small office made smaller by the presence of a life-size papier-mâché gentleman, in the basement of Rice Hall. Because he was my first real writing teacher, I loved Stuart, worshipped him, and hated him sometimes too. His critical approach to my work was well beyond my understanding at the time, but he patiently discovered a way for us to work together. That too was one of his many strengths as a teacher: the ability to see deeply enough into his students’ writing that he could help direct them down a road that would be most fulfilling, but only if you worked hard enough, that was always part of the deal. In addition to the many first poems I wrote under Stuart’s guidance, I also began to read quite a bit more then I was used to. One night I felt my head was spinning and so I stopped and counted and realized I was reading nearly a book a day. During our conferences Stuart would often begin by saying, “Have you read…,” and before he could name the book, I already knew the answer, and I would remember the title and walk from his office to the library to find it. As his student in an Independent Study class, of which I took more than a few, I had Stuart’s undivided attention, and it felt good, even if the criticism was stiff. It was often stiff, and difficult, and sometimes even without mercy, but it was always honest, and to be able to count on that honesty is a rare thing in a writer’s life, especially a young writer. For that rigor I will always be grateful.

I will also be grateful for the many examples of Stuart’s poems that taught me so much about how to make a poem real and how to make a belief enduring. The arc of Stuart’s work as a poet can be looked at as a long journey towards, and then beyond, self-knowledge. In the best of his poems he has managed to strip everything down to its bare essentials in order to see clearly what remains of who we really are. Because he also read, wrote, and published widely in German, his regard for his native English is more inclusive than most other poets of his generation, and more imaginative in its focus on how to say a thing straight. I remember feeling free under the wing of that teaching and feeling like there wasn’t anything I couldn’t do as a writer, as long as I remembered what was truly important.

Although I have much more to say about my time with Stuart, as I said earlier, that is a subject for another time. Instead I want to proudly proclaim Stuart’s stake in contemporary letters. His wide range of writing that includes dozens of books of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, criticism, and translation represent a remarkable achievement; that he accomplished all of this while being a caring and devoted teacher is even more remarkable. It seemed to me that in class or in an Independent Study, Stuart would never hesitate to give up everything he held in his limitless imagination at that particular moment, for the sake of a single lesson learned. I came to admire what I saw as his selflessness as a teacher and came to recognize that he was not only teaching me to be a poet, but also how to live in the world without getting in my own way.

During the thirty years that I taught in three universities and a community college, it was to Stuart’s teaching that I most often turned to for guidance as a teacher myself. It pleases me to think that my own students, who have gone on to be publishing writers and teachers of writing, are doing so in such a way as to illustrate Stuart’s almost magical approach to teaching writing. I learned from him and they from me, as their students are learning now from them.

I like to imagine that this continuity, like the distinguished body of his work, is one of the ways to keep Stuart’s memory alive, which is how it should be. It seems to me that we need good teaching now more than ever, and that teachers should do more than teach their academic specialties. As Stuart did, they should also teach compassion, an unflinching devotion to the love of words, and a hardy work ethic to get one’s students through the initial years of study and youthful experimentation on their way to becoming writers in the world. Stuart taught us these things and above all he tried to teach us why poetry matters. I asked him that question once, groggy from sleep and grumpy over the fact that I had an early conference with Stuart for which I wasn’t prepared. His response was to take my question seriously. He spoke well beyond my allotted conference time while other students began to gather for their turn outside, while I sat there in my shame, and what I learned that day was that this question – why poetry matters – is not an academic question, that there are no theories involved really, no axioms to help us arrive at an answer, no algorithms to measure the depth of an image. I had my first glimpse that day of the beauty that can be found in the objective reality that surrounds us. I learned that day that for those of us drawn to a life of poetry, asking why poetry matters is the same as asking why being alive matters. I learned that day that poetry matters because it represents the possibility of opening up our souls in such a way as to allow others some inward vision there, some insights into the powerful way we share as writers the grief of the world and its joys. I learned that poetry matters because it teaches us a disciplined emotion, necessary to tell a righteous version of historical events in these troubled times. Poetry matters, our teacher told us, because it has the power to bring people from thousands of different languages together in a collaborative search for words that are pure and clear. Poetry matters for the way it keeps song alive in our lives, and for the way that the drum beat of poetry rocks our bodies into dance. Poetry matters the way bread matters. Poetry matters because it allows us to hear the bells, no matter what they ring out. I am forever grateful for these lessons, and in awe of how powerfully they represent what is most important and most enduring in poetry.

I clearly lied when I said that I wanted to avoid writing about my relationship to Stuart, so I want to add some lines from him here, a short poem of his from an early collection called Up in Bed, because it’s a poem that allowed me to see something amazing at the time, something that now I can call the beauty of who we are in our world, and that from even the most fractured and overwhelming experience one can discern a bright star of understanding. The poem is called “Out of Habit,” and I quote it in its entirety here:

Standing in the shadow of the table,

scarcely looking at the food I serve

you, What is this stone in the soup?

you ask politely. It came secretly,

it is not from this region, I say.

It feels sorry for itself,

it is natural science out of habit,

hinting a change in our magnetic field,

small but moving gravely toward your

spoon now. Can this stone mean so

little to you? Swallow it whole!

I am grateful also to the contributors to this Special Feature, including some of America’s most celebrated poets of the last twenty years, all of whom had the opportunity to learn from a master the complexities of our craft and sullen Art, as Thomas called it. These essays range widely in their focus but have in common the celebration of the enduring power of Stuart’s teaching, and they almost all point to single, particular moments during which Stuart led them to some insight into poetry that did nothing short of change their lives.

When I read these essays, I have to wonder about the energy Stuart must have had to so deeply engage and influence so many young writers for such a long time. He taught me many things as a writer and teacher of writing, but he never taught me how to maintain that level of energy. To the end I know that Stuart was alert and active and full of poetry with a level of focus and energy that I envy. That sentiment and many other are expressed beautifully in the essays gathered here, and each in its own particular way is illustrative of Stuart’s astonishing devotion to poetry and to teaching. There are too many essays gathered here – nineteen in all – for me to discuss each one of them, but let me say that they range from the wildly lyrical to the rigorously academic, from solemn observances to truly heartbroken goodbyes, and to joyous celebration for what we all once held in our hands thanks to the generosity and the deeply abiding kindness of our teacher.

Because I moved back to Oberlin after twenty-five years of teaching at three different state universities, I had the opportunity to spend more time with Stuart. When I returned, Stuart had already retired from teaching, although he was in regular contact with many of his former students, more than a few of whom would knock on Stuart and Diane’s door if they happened to be in town. Stuart had nearly retired from writing at the time as well and went through a brief period of believing that he’d already written and published enough. Fortunately, this feeling passed, and he had some remarkably productive final several years of his life, publishing more than a dozen books of poetry, prose, and translation. Eventually, Stuart and Diane became my wife’s and my double-date. This has nothing to do with poetry. This has everything to do with poetry. Those dates – most often dinner and drinks – were a feast for me. I relished the opportunity to sit across from my teacher again. I knew that I still had much to learn from him. I can remember those evenings in great detail, the way I can remember every inning of a few baseball games I played in more than fifty years ago. I can tell you that they were rich in the telling of the world, and not without many toasts to the great ones we professed to follow, and to each other. And what is distinctly Stuart’s as a poet is the way his poems are a clear invitation to the many of us out here trying to find our way. An invitation to see the world clearly by squinting through the haze of time and space. An invitation to be brave with words and honest about what we feel. This, you could say, is Stuart’s greatest legacy.

I want to offer my special thanks to Dore Kiesselbach who did the yeoman’s share of the work on this Special Feature and who provides an elegant closing essay. Thanks also to Diane Vreuls, for her permission to proceed, and to Stephen and Sarah Friebert for their encouragement. We are also grateful to David Young for his good counsel. Thanks finally to Danny Lawless for putting a roof over our heads, and for sharing space in these pages for our tribute.

Margaret Atwood

Stuart Friebert: An Appreciation

I first met Stuart Friebert in the 1970s, through FIELD magazine. FIELD – of which Stuart was a co-founder – was a poetry magazine, one of those paper mushrooms thrown up by the vast underground network of filaments that connected poets in those days. Stuart himself was a poet, and an editor of poets, and a translator of poets, and an appreciator of poets.

In fact he was one of the world’s great appreciators: the ability to appreciate is a gift, and Stuart had this gift in abundance. I’m sure many received written appreciations from Stuart of the kind I myself received: capital letters, superlatives, exclamation marks. These appreciations were the obverse of hate mail, except that Stuart didn’t underline words with colored pencils.

Why was FIELD called FIELD? I haven’t wondered that until now. Force field? Field of endeavor? Or “field” in the democratic sense: level playing field, with all kinds of things in them – crops, lost dimes, cows, buttercups, thistles, old shoes, birds, discarded bottles, beetles rolling balls of dung. And such was Stuart’s FIELD: abundant, varied, with always some unexpected treasure.

I first met Stuart in person in 1977, when he invited me (and, perforce, my one year old) to Oberlin College to give a reading. He was then what we know him to have been since: considerate, kindly, funny, interested, and wildly enthusiastic about poetry and writing. I think of him as the best sort of a certain kind of middle-of-the-continent American – with a down-homey forthrightness and four-square honesty that would seem implausible if it were in a movie. Stuart felt familiar to me at this first meeting, as if I’d known him for a long time. I’d had uncles like that, though they hadn’t gone in for poetry.

We kept up with each other after that, mostly through the mails and then the emails, over the years that somehow went by too quickly, as years do. It was amazing how much Stuart wrote over those years – not only poetry – and how consistently well. There were hidden depths – everyone has some, and you can’t be a poet without sadnesses; rather, you can’t be a human being without them. In some poets regrets can turn to bitterness, but this did not seem to be true of Stuart. He wished well, to so many people, about so many things. Another gift, the ability to be so single-heartedly positive about the achievements of others.

His translations, too, have given me a lot of pleasure. I have just enough German to know how good they are. Very few are able to enter the linguistic universe of another, and transmute, and bring back treasure.

A week before writing this, I received a package in the mail. It was from German poet Ute Von Funcke – Shadow of Shadows, Selected Poems, translated by Stuart, his last work. Ute enclosed a little note: I should think of this book as Stuart waving to me across the Atlantic Ocean, she said.

And so I do think of it this way, and I’m waving back. Hello and farewell, dear poet friend. It’s been an unmixed pleasure. Truly.

Sylva Fischerová

For Stuart: A Eulogy on Gratefulness

Being grateful is a virtue that costs nothing. What follows is none other than a eulogy on gratefulness.

First of all, I am grateful to Miroslav Holub for having introduced me to Stuart Friebert in the beginning of the nineties when the Iron Curtain had fallen and a new life had begun for all of us who had lived behind it. Second, I am grateful to Stuart for having invited me to his “translation school” in the beginning of this millennium. The idea of translating my poems into English was his – and I was reluctant at first, because Stuart, in spite of his Czech grandma, did not speak Czech, and I never studied English as a subject and had never lived in an English-speaking country: not a good combination. But Stuart replied immediately: “We can just try.” We did – and it worked!

To be honest, it worked, or began to work during a rather long process which was no idyll at all – on the contrary, we almost had fist fights via email which, however, usually ended with Stuart’s laconic statement: “Sounds translated.” – That was the gospel, there was no way around it. Not surprisingly, then, when The Swing in the Middle of Chaos, our first book of poems in translation published by Bloodaxe appeared, and David Vaughan, the British journalist and author settled in Prague, made an interview with me for Radio Prague, he began with: “When you read poetry in translation, you nearly always know that you are reading a translation. I did not have that feeling when reading this collection.” – Bingo! That was exactly the point. So I learned my lesson and now I’m passing it on: when translating Pindar’s Pythian odes, together with a former student of mine (and Pindar’s poetry is, to put it mildly, untranslatable), I told him a hundred times: “No, we can’t have it like that: ‘sounds translated,’ as Stuart would say.”

But I am grateful to Stuart for so much more than lessons in the art of translation. Thanks to him and to his efforts, I made a poetry reading tour across the USA in 2010, and also in 2014 (with the invaluable help of Robin Davidson from Calypso Editions). Inspired by the first trip, I wrote a “fictitious travelogue” Europe Is Like a Thonet Chair, America Is a Right Angle which has been translated into German, and the Polish translation will appear soon; during my second journey, I wrote “An American Quartet” – a poetic counterpart of the first book. Without Stuart, these works – trying to say something about the Old and New World as well – simply would not have been written. I also remember a moment when Wayne Miller – a former student of Stuart’s who was my host in Kansas City – explained to me the lesson he was taught by Stuart about what literature can look like: he quoted as an example Max Frisch’s Man in the Holocene. And that was Stuart – inspired and inspiring but at the same time highly critical: a radiant person sending energy in all directions, with his unique and inimitable sense of humor.

I am grateful to Stuart also for sharing with me – in addition to the pictures of birds & fishes & flowers and other creatures that ensoul the universe together with us – his favorite saying of Chinese poet Du Fu’s:

“Life is good if you have a job that earns you enough wine & time to write crazy poems.”

Once again bingo!

Coming to the end of my eulogy: I am grateful to Stuart also for his “olé!”, the final punctum of lots of his emails; and this is maybe something we should follow, and taste and toast: Let’s go on! – Let’s proceed! – Olé!

Marianne Boruch

Thoughts toward the rave for Stuart

When I began sending out work in 1979, everything went first to Oberlin College’s wonderful journal FIELD in the customary small batches. Except I was sending from Taiwan where my husband and I had landed teaching jobs. So, into those overseas tissue-paper blue envelopes I slipped the required SASE though not the standard E but a postcard, the airmail version. In near epic boomerang fashion, note after note came back in Stuart’s big magic marker: CLOSE! or ALMOST! Finally, and with no hope, I had 7 poems left to send. Grrrr. But unbelievably, yes! They (that is, Stuart, David Young, and Alberta Turner) took two.

Those postcards and Stuart’s big magic marker’s rapid-fire reply—faster than most email exchanges–were my introduction to one of the most valuable, loving spirits on the planet, opening to what seems a lifetime now of good feeling for which I’ve always been grateful. But here’s the thing: even Stuart’s rejections carried the unimaginable cheer and encouragement so characteristic of him. Those exclamation points (Almost! Close!). His relaxed loopy cursive full of warmth. Somewhere in my cluttered house, I still have those postcards. When we move or I die, these treasures will be found.

I’ve been rereading his poems these past few weeks, marveling again at how much of the world they welcome. An honest world full of beloveds and vulnerable wise guy malcontents and those burdened but rarely destroyed. A world where scientist-poets run serious labs to deepen what we know, worlds crisscrossed by languages and curiosity and history and lyric turn-on-a-dime insight, a world of common injustice and uncommon joy. An unshakable wit too, never self-serving, along for the ride.

In the last two years, Stuart and I picked up our correspondence in e-earnest. In one exchange last April he wrote:

Aside from minor insults re our being late-octs now, we managed to stay FREE & CLEAR

of the virus, but it’s more of a struggle to escape “Agent Orange’s” poisons (Spike Lee’s

moniker for the Trumpster)…. Just trying to accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative,

(we even bang out the whole song when really stressed) ….

His loss, so hard to bear.

But Stuart, you’ll still here. Fact: this sang out to me again earlier today–

… Now that I’m going step by step

evening comes on nice and slow by the time I’m in

the middle of the street, taking a little breath, closing

an eye. The best light’s gone. I remember I wanted

to force some things, I remember the cat’s limp but

little of the dog. I remember if you want to catch big

fish, keep to half-clear water, the middle. If you look

to shore, there’s a steepled house with an old man

tucked in bed reading all this while. Call him Doppel-

gänger but keep on going. Even if it’s really late, he

lights his dock, just keep on rowing, all the way to sea.

(from “Step by Step,” Stuart Friebert, Decanting: Selected & New Poems, Long Horse Press, 2017)

Ute von Funcke

Meeting Stuart

It was in spring 2017 when my publishers, scaneg Verlag, sent my third poetry volume, Woman Taking Flight, to Stuart Friebert, with whom they had been cooperating closely for many years. I didn’t know then that this would be the beginning of an intense, most wonderful partnership.

In a short time, I got an email, written in strikingly good German, with some translated poems attached. Vibrating energy, Stuart’s translations seemed like music, making transparent the essence of my poems. For me it was magic, a coup de foudre.

Only manifold experience, excellent knowledge of the German language, sensitivity and wide knowledge could have created this noble art of translating.

To and fro emails flew; our work was like a ping-pong match played on the huge Oceanic table.

We not only shared our work but many of his wide-spread interests too. There was hardly any field which he hadn’t knowledge of, be it modern art and music (he loved avant-garde composers like Hindemith and Luigi Nono) or world literature and science. And I loved his humorous anecdotes sprinkled in between our literary exchange. How exciting “listening” to his stories, e.g. the one of Peter Bichsel, a well-known Swiss author: Stuart and he sat at the bar of an Italian restaurant. An old farmer next to them asked Peter what his profession was. Peter said, “Author.” The farmer hugged him and cried “Wonderful! I myself am a reader.”

Later when Stuart was teaching the German language and literature at university he often travelled to Europe, sometimes with his family, e.g. Switzerland where they stayed for a longer time. He always said how thankful he was for the support of his wife, wonderful Diane Vreuls, and of his children; he knew that without their help he couldn’t have realized his many projects.

How happy he was to visit well-known German authors like Günther Eich, Ilse Aichinger, Karl Krolow, Günther Grass, and many others of a generation who named the horrors of the Nazi regime and fought against apathy and oppression.

I have wondered how Stuart had managed to invite writers even from East Germany to Oberlin, how they were able to get permission to travel to the USA at a time when the former DDR policy did not allow private persons, especially artists, to travel outside their enclosed region. Adventurous Stuart also succeeded in travelling behind the Iron Curtain to visit authors there, to give them a chance of publication, at least in translation, in America.

Stuart stood as a bridge builder between America and Germany for a long time. His reward was to see the rich results of his engaged work, and to have experienced the deep thankfulness of those writers and readers, present and future, who have benefitted from his efforts.

The true marvel is language, the most human trait we have.

“Time is short, be quick to love” is a line of an old prayer which Stuart recited.

* * *

Ute von Funcke’s contribution originally appeared in a longer form in Issue 82 of the online journal Offcourse edited by Ricardo and Isabel Nirenberg. It is republished here with gratefully acknowledged permission. The full version of the essay together with a link to Stuart’s many contributions to Offcourse over the years—poetry, prose and translations—may be found here:

https://www.albany.edu/offcourse/index82_permanent.html

Thomas Wild

You’ve Just had Friendship Redefined

Remembering Stuart Friebert

Ach was one of his favorite words. He’d write it with an exclamation mark, astonished or wondering; or, followed by three dots, impishly grinning; or, without any addition, in compassion for someone’s pain or sorrow. Ach is an utterly German word, you can find it from the eminent poet Heinrich von Kleist to the equally eminent comedian Vicco von Bülow, best known as Loriot. These three letters are untranslatable, yet you can sense them, they’re a sound on the threshold to a word, a poet’s best friend, unceasingly alive. All who encountered Stuart, in person or in writing, could experience this in every gesture, in every word: his curiosity, warmth, wit. A particular form of kindness that is delighted by the fact that this English word entails a Kind, a child, open and vulnerable, unruly, and full of imagination.

His first actual encounter with the German language is preceded by questions. Why German to begin with? The thought alone that he would have to defend this to his Jewish grandmother in Milwaukee in 1944 made him tearful. Will he bring the Germans to justice after the war, as his mother envisioned? He indeed embarks for Darmstadt, Germany, in the late 1940s as one of the first exchange students from the United States. What captivates him about German is its sound: Goethe, Heine, Büchner, Rilke. So he ends up arriving in this faraway country not as a judge but as a poet who he will have become one day. That’s how Howard, Stuart’s alter ego, experiences it in the wonderful prose memoir The Language of the Enemy (2015).

Years later, Stuart Friebert, now a professor of German at Oberlin College, is awarded a prestigious fellowship to do research in Germany for twelve months. Upon his return, he asks the president of the college for a meeting. He needs to pay back the stipend, Stuart opens the conversation. Why in the world? What happened? His superior wants to know. Well, Stuart replies in shame, instead of fulfilling his research plan he wrote two volumes of poetry. Across the table, a pair of eyes lights up. The rest is history: Stuart Friebert founds Oberlin College’s Creative Writing program, FIELD Magazine, the FIELD Translation Series and Oberlin College Press.

From that moment on, Stuart Friebert literally wrote and translated every single day of his life. He published fifteen books of his own poetry and four volumes of prose, mostly in English but several also originally written in German. He edited three seminal anthologies on American poetry and poetics. And Stuart published sixteen volumes of poetry in translation. The fact that distinguished German poets such as Günter Eich, Karl Krolow, and Kuno Raeber are available to the English reader is thanks to Stuart’s work. Collaboration was his favorite format in all of this, especially with the anthologies and most of the translations. Writing meant to Stuart, first and foremost, to be connected to something and with someone.

Stuart once invited me to write together what he called ping-pong-poems: he sends two opening lines, I add two of my own and send all four back, he continues with two further verses etc. until a poem, or something like that is there. He suggested we write in German. I loved this playful back and forth, the combination of corresponding and writing. Let’s send out a couple to some magazines, he suddenly proposed. I was hesitant, he persuaded me. A year or so later, we received printed issues of a fairly prominent literary journal that decided to take on one of our missives. After we’d opened the mail, we immediately called each other up. They had placed our ping-pong-piece between poems by Friederike Mayröcker and Elfriede Jelinek – a recent laureate of Germany’s national book award and the Nobel Prize, respectively. On the phone, we hysterically hoped the jokester in the editorial staff wouldn’t get fired because of this mishap granting us such a splendid giggle.

I never studied with Stuart Friebert but he must have been a superb teacher. Tankred Dorst liked to tell an exemplary story from the time when he was a writer-in-residence at Oberlin many years ago. He and Stuart team-taught a class on Romantic literature. At some point, Dorst asks the class: Which medium would the Romantics choose if they lived today? After a moment of silence and with a big smile on his face Stuart offered: Film! Sometimes, a two-line dialog between poetic thinkers can replace a shelf of textbooks.

Stuart’s ample correspondence would be worth its own publication, I assume. I can hardly think of anybody else who invited you with such charm, playfulness, and kindness to respond – without ever requesting exactly this. It’s now our responsibility who survive him to open up new possibilities for responding. Thank you, Dore, for this opening step!

The young people, including those who are not so young any more, must be many whom Stuart told simply through the way he spoke, wrote, moved: You can do this, to live a life out of love for language and literature. Just like that. As long as humor is involved! He loved to inscribe the books and journals sharing his latest works with “More words” – ironically and invitingly at the same time, like a motto.

In one passage of The Language of the Enemy, Howard articulates an experience that will accompany his life as it accompanies many who have experienced Stuart as a writer, mentor, playmate: “You’ve just had friendship redefined.”

Vijay Seshadri

Stuart Friebert

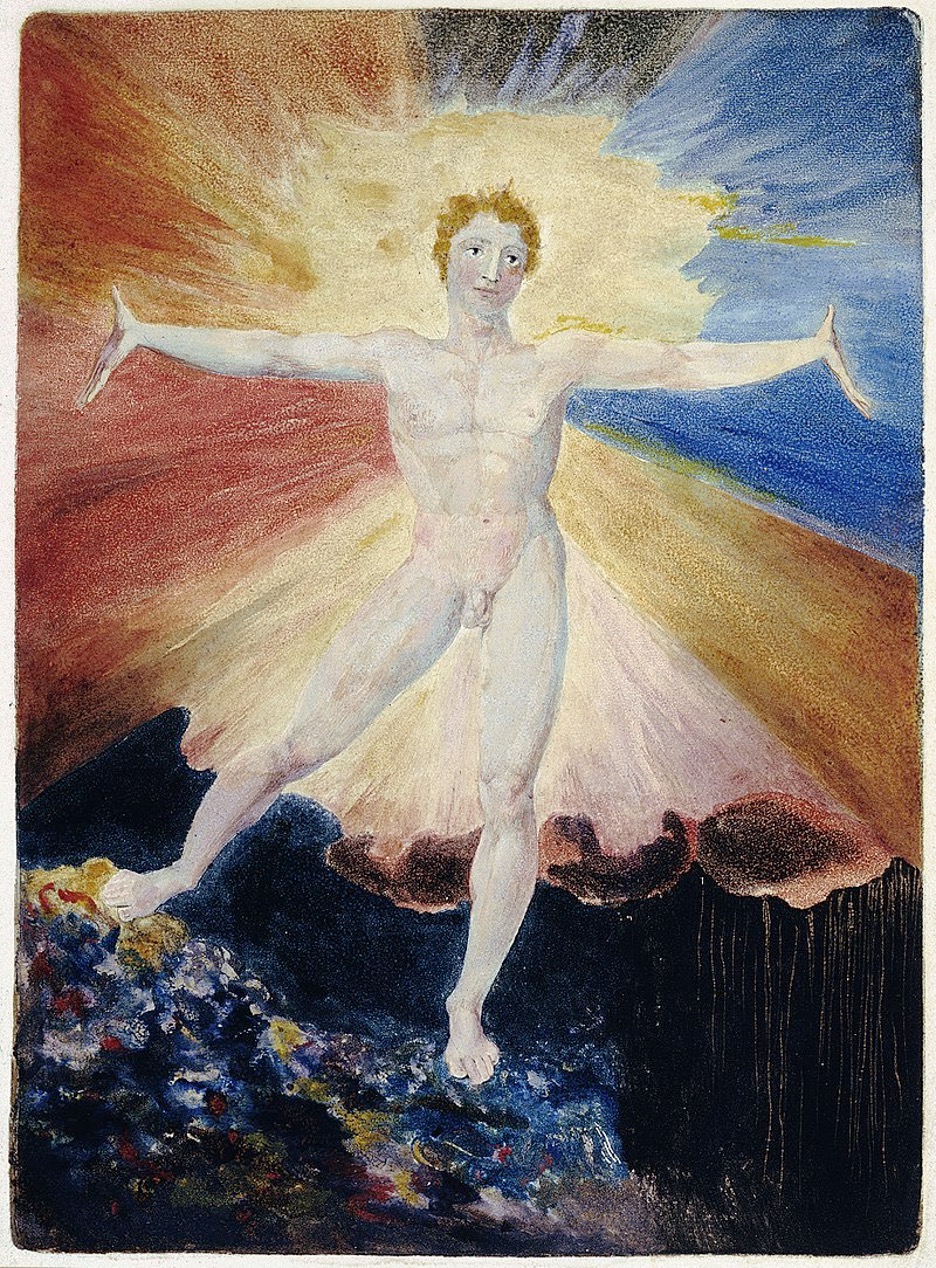

I didn’t know Stuart Friebert when I was at Oberlin; and our paths never crossed afterward. Among, though, the numberless people I haven’t known, Stuart had a dramatically consequential effect on my life. That was because of the civilization of poetry that he and David Young and others had just fashioned when I arrived at the college in 1970. When I think back to that civilization now, the resplendent, Vitruvian figure of the Blake-colored print “Glad Day” immediately pops into my mind—an association that isn’t at all far-fetched and is in fact just the opposite. From its birth, in 1969, FIELD magazine was a major force in American poetry in what might have been American poetry’s most glorious period. Highly individuated, clear, and decisive in its allegiances, beautifully designed and laid out, deeply committed to translation, especially translation from the other Europes, the northern, middle, and eastern ones, the magazine was at the center of the tremendous revolutionary poetic activity of that revolutionary period. The reading series at the college brought a long train of poets at the beginning or in the middle of their careers who would make the literary landscape of their era—among many others, Louise Glück (slender, grave, with one book to her name and no prizes), Margaret Atwood, Galway Kinnell, W. S. Merwin, Mark Strand, Tomas Tranströmer, Kenneth Koch, Amiri Baraka, Denise Levertov. (Mythic figures, still, to me, because of the age at which I encountered them.) Decades before creative-writing programs became commonplace, the college seemed saturated with poetry, saturated out of its own inner being, and in that saturation Stuart played a central part.

I came to Oberlin raw and excessively young, from a deep, though accidental, isolation. My family and I had been in the country for ten years, ten seething, tumultuous years for America. We’d hardly got our bearings, which might be why my parents, confined as they were to an occupational notion of our identity in our new world, took it for granted that I would become a scientist, a mathematician, or, at worst, a doctor. But I was almost immediately, almost helplessly, drawn to the powerful, luminous Oberlin poetry civilization that Stuart played such a large part in making. My curiosity about that world was intense and is still vivid to my memory. I hovered around its edges, I surreptitiously climbed its walls and peered into its secret gardens. I breathed its air in, which made me a poet, it turned out, long before I knew I was one. Stuart’s role in this might have been the most significant precisely because I didn’t know him. David Young, of course, was as crucial to that world as Stuart was, but I knew David my entire career at the college. David was the instructor of my first semester, first-year English 101 class, an introduction to drama. Later I studied Shakespeare with him. David for me was about the actual agonies of learning and writing and finishing, or not finishing, work. He was, and remains, for me, a person. Because Stuart was distant, he was a figure, an archetype, an embodiment not of pedagogy but of literature itself. I exercised my imagination on him. He had a Mitteleuropa glamour for me, and in my mind an associated way and style of being in the world. He was not in Lorain County but on the Continent, hanging out with Günther Eich and Vasko Popa. His duties to the world well-attended to, he was living his real life. I wanted to do that, too. I can still see him so clearly. He has an Amish beard and is wearing a loose black-and-purple-striped velour pullover and baggy khakis. His gaze is abstracted. He’s thinking of something and fashioning something in his head.

Linda Gregerson

Brief Reflection: Stuart Friebert

The poem was truly awful: portentous, mannered, overstuffed with a reaching-after-effect. The author was very young; perhaps no one had ever thought to tell her that poems didn’t have to sound this way. Stuart had kindly agreed to teach a guest workshop at UMBC, the University of Maryland Baltimore County, and a small group of aspiring poets had assembled for the purpose in an uncongenial cinder-block classroom.

The author read her poem aloud, upholstered as it was in artful obscurity. Silence. “I’m so sorry,” said Stuart, “but [and here he spoke with infinite deference, as though the problem were his own thick-headedness] could you just tell me what this poem is about?” The author blushed, gathered her confidence, began: “Noah,” she said. And then, fearing she was belaboring the obvious, “Of course.” And hesitantly, charmingly: “. . . had to decide.” A pause. Then further explanation: “Who should come and who should go.” Ah. The subject of all this grandiosity had been the loading of the Ark. And all this while, and as she continued, Stuart was writing on the page in front of him:

Noah, of course,

had to decide,

who should come

who should go . . .

And when this very young undergraduate at what was then a regional commuter school stopped speaking, he turned the page around and showed her the result: a lovely, disarming, and genuine poem, in her own voice. In one brief fifteen-minute patch of time, he had taught her more about poetry, and had taught me more about teaching, than others could have done in a lifetime.

Far more importantly, he had taught me once again, as he so often had before and would again, about the extraordinary power of listening. Stuart was a genius of a teacher; generations of students, friends, and even mere acquaintances have reason to thank their lucky stars for him. In the cause of poetry, he was a proselytizer unparalleled. “You’re taking it all away,” he’d said to me a year before; “You need to start writing poems.” “Stuart,” I said, “I don’t even know what a contemporary poem is supposed to do. I read plays. I read novels. I can read John Donne. When I open an issue of FIELD it makes no sense to me.” And so my instruction began.

Only a true believer in the art could possibly have imagined I had anything in me that could lead to poetry. Let’s call Stuart’s comment a generous misattribution. Nothing had ever indicated that I had a shred of aptitude. At stake was simply his unfaltering faith in poetry, his bred-in-the-marrow conviction that poetry is the breath of life, that poems are for everyone, that anyone with half a heart and the smallest spark of mindfulness not only can but needs to write poetry. It took me years of mortifying and ungainly attempts before I began to understand what he was telling me. I owe him all.

Martha Collins

Remembering Stuart

Stuart Friebert brought me good news, good cheer, and good advice throughout the nearly forty years I knew him. All of which was a lovely background to the fact that he changed my life in poetry at two different times, in two very important ways.

The first began at a poetry festival, where I was the least well-known poet in a line-up of readers that included Stuart. With his usual warmth and good humor, he suggested that I send some poems to FIELD. The magazine turned those down, but Stuart wrote: “Send more!” This time, when the reply came, Stuart had scribbled in the upper left-hand corner of the envelope: “Yes!! FIELD!”

I continued to publish in FIELD for the next sixteen years, always sending to Stuart, always receiving a reply that made me smile if not laugh. His abbreviations and exclamation points were enduringly funny, his comments always insightful. I don’t think that magazine editors are usually the best critics of one’s work: taste is taste. But I began, as I corresponded with Stuart, to trust FIELD in just that way. I was always delighted when, on behalf of the editors, he enthusiastically accepted my poems; but I also trusted what he said when the magazine turned something down or wondered about a line or phrase. His advice was always specific, and it was always warm. Through him, I felt I had found a poetry home.

And then, in 1996, he suggested that I apply for the impossible job of replacing him on the Oberlin faculty. As the shepherd of several job applicants the next spring, he introduced me to a thriving creative writing program with such enthusiasm that I ended up going to Oberlin for the next ten years, splitting a full-time position with Pamela Alexander.

Neither of us knew what it would mean to replace Stuart, though a note from an outside program reviewer had warned that it would take at least two people to do so. One of the founders of the creative writing program, he was for many years its director and often its only full-time faculty member. His work was heroic, and it was impossible to replicate.

I sadly never had the opportunity to work directly with him. But he’d left his mark on every aspect of the creative writing program, and while he wisely didn’t attempt to influence either the program or the magazine after he retired, his presence was a joy during my Oberlin years. I’ll never forget our delightful breakfasts, full of laughter and poetry and insights, often accompanied by a presentation of his latest book of poems or translations. If he’d done the work of several people while he was teaching and editing FIELD, in his retirement he put that energy into writing.

It was an admirable career, and he was an amazing person. I’m grateful to have known him and been supported by him for all those very good years.

Diane Louie

Six Brief Reflections on Tee Hee

There’s a lot of sly laughter in Stuart Friebert’s poems. And a lot of argumentation. A lot of detailed evidence with a lot of concurrent winking. The poems are the work of a grappler, a pusher and puller of meaning, details hovering like so many pinging electrons outlining some improbable life lived into precision and amplified spirit. As if the poet took G-d by the shoulder, shook some meaning out of the Universe for all of us down here.

I remember sitting in Stuart’s small office in the Rice Hall basement. Seated beside the bookshelves was a life-sized papier-mâché person. A sculpture by Norman Tinker, legs crossed, pensive. Stuart would ask me to read what I’d brought. Audience of two, one more pensive than the other. Hmmm, Stuart might say. That meant not too bad, maybe there’s something there. Ahhhh, he sometimes said. That meant good. And one time, under his breath: you might be up there with ... That was the best. To be in the company of Stuart’s regard was to be with people of letters, people grappling with life. Life given meaning by a papier-mâché jest.

His was a yes and no kind of teaching, which for me was ideal, the firmness and no-nonsense-ness. One time he told me I could not use a word – it might have been obstreperous, or obsequious – because it wasn’t my word. I was saying something about clouds. He was right. But still I objected, though not to his face. I was determined to find the vessel that could hold that word. Which is what he (wink wink) intended all along.

In 1979 Stuart accompanied me to the Datsun dealership in Cleveland so I could buy a car for my new life in graduate school, further in the midwestern heartland. Standing in the glass-walled showroom, Stuart explained with all his emphatic straight-faced enthusiasm that he was my brother looking out for me, and the salesman had better give me a good deal or else. After hours of test-driving, the salesman threw in four tickets to the Cleveland Indians, which for Stuart clinched the deal.

One recent summer visit after a picnic (“bulk your paddlers up”) we paddle-boated the length of Wellington Reservoir. While Diane and I pedaled, Stuart, with a bad hip, lounged and told stories. What a story teller! Uncompromising and a softy, both. Reverent and fierce, demanding and profoundly generous. In the poems he let juxtapositions do the work revealing the Universe’s madcap prank. In his emails, he signaled meaning with his parenthetical tee hee hee. In person, he alternately lowered his voice with the seriousness of it all, and then grinned with delight.

Stuart’s last email to me started with a question, which I didn’t realize was more than playfully rhetorical until after I understood it was his last email. Monarchs, Stuart, like you – your very name, French form of Stewart, from steward, guardian of the household. As teacher, mentor, colleague, friend … and sibling. We were – and in the generosity of your words, we are – so blessed. Miss you dear bro’

David St. John

Stuart the Redeemer!

When I arrived to teach at Oberlin College—my very first academic job and a part-time one at that—in the late summer of 1975, I still hadn’t met Stuart Friebert even though we’d corresponded a few times the previous year about things related to FIELD. Most often I’d write back-and-forth with Tom Lux, who I was now coming to replace after he ‘d left to teach at Emerson College.

Stuart had been away traveling during my whirlwind job interview late in the previous spring, though I’d been able to have a great leisurely hour with David Young (talking about poetry and FIELD, where I’d be part of the editorial board if I got the job) amid the other meetings with the scholars in the department and a few members of the Faculty Council.

Yet, it didn’t seem to matter if the conversation was about Wordsworth, or the history of Oberlin, or Milton’s daughters, or the one movie theater in town, or how to teach Eliot; in every instance the faculty or administrative person leading that hour’s interview would, inevitably, simply stop dead in their conversational tracks and say, “Have you met Stuart Friebert yet?” In each instance, I’d reply, regretfully, “No, not yet, but I’m looking forward to it.” The lesson I learned that very first day—and would continue to learn over the next two years—was that Stuart Friebert, even in his absence, loomed larger than life in the environs of Rice Hall.

The first few weeks of that fall semester were a blur for me, meeting my new classes and finding my way around a totally unfamiliar campus. I’d already discovered that the poets in my class were staggeringly good, and the best-read undergraduate students in poetry I could have ever imagined. Almost all were Creative Writing majors and so they’d had Stuart as their advisor. When I asked about their previous writing classes (they were juniors or seniors), they made clear that as freshman they’d all first been through “poetry boot camp with Stuart,” then a kind of poetry immersion in David Young’s brilliance, followed by Tom Lux’s legendary, electrifying lessons in “Poetry, Literature & the Art of Life As Recreation.”

I saw that I was, without question, the very new kid in town. I decided that I had to meet Stuart, so I asked one of the students, Marti Moody, to remind me where I could find his office. “That’s easy, “Marti said, “just go down to the basement of Rice and look for the line of students outside an office door.” Sure enough, for those first two weeks, every time I looked down the otherwise empty hallway toward Stuart’s office, there was such a long line of students that I never made it all the way to his door.

That Saturday, at the end of my second week, we were scheduled to have the first editorial meeting of the year for FIELD, where I knew I would see Stuart for the first time. I decided to go a little early to see if I could finally introduce myself before the business of the meeting began. It was one of those wickedly humid early autumn days, with heavy clouds rolling in, and by the time I walked from my car to the door of Rice Hall, I was already totally drenched by a midday thunderstorm. After I’d made it down the stairs to the basement of Rice, I stood there a moment to let an astonishing amount of water continue to pour off me—and my insufficient nylon jacket—before walking down the hall to the FIELD meeting.

I was still feeling slightly adrift in my new surroundings and new job. The sense of unfamiliarity was clinging to me more than I’d anticipated. But as I turned in the direction of Stuart’s office, I saw a large—looming—figure standing at the very end of the hallway, perfectly still, his arms outstretched to either side in a posture of benediction or waiting embrace. I felt exactly as if I’d stepped into the old Brazilian movie I’d once seen and become a lone sailor in his rickety sailboat at the moment he comes near enough to Guanabara Bay and Rio de Janeiro to see the statue of Christ the Redeemer in the distance, an image offering safe harbor, a little rest and consolation.

As I walked slowly toward the unmistakable figure of Stuart, his arms still open wide, somehow backlit as the storm broke and the sun began shining through the clouds (I never could figure out how he’d arranged that), I began to feel the same sense of relief, recognition and permission that his students must have felt as well. I knew things were going to be ok.

“David St. John,” Stuart said as those benevolent arms wrapped me in his huge embrace. “At last!”

Annette Barnes

The Appleseed Poet

In 2010 my email pal Stuart Friebert wrote:

wanna write a poem together, alternating lines? (an honorable tradition as you may know): see attached, your move!

I, a seasoned philosopher but neophyte poet, jumped at the chance. When I opened the attachment:

Tolstoy Learned To Ride A Bike & Play Tennis

At An Age When Most Of Us Cash in Chips

it was not, however, obvious what my first move would be. Then I remembered an extraordinary parade I had seen in Atlanta, Georgia and ventured:

But unlike Lester Maddox he did not ride

it backwards.

Stuart’s response:

You will strain to make any

connection betwixt them,

suggested it was not a good first move. But Stuart liked the idea of the parade, so he had us begin:

There we were, watching the parade, while he climbed up

on a curb stool to see what he could see. At first he seemed

(as I had been)

confounded by mothers in curlers marching behind infantine

baton twirlers and

so Tolstoy, according to Stuart:

thought of setting off into the forest in one

of his long lonely walks, smashing twigs in his way, cursing

under his breath.

The next image inspired by Miss Tall America throwing candies to the spectators:

but when the beauty queen threw a candle

to him from her guttering crown,

Stuart thought:

he shifted from one gimpy leg

to another to catch it.

It was at this point that I suggested bringing in a backward riding bicyclist. Stuart wanted it to be a clown:

Riding his bicycle backwards the clown pulled

off his jacket, turned a sleeve inside out, and flung it at Tolstoy.

When at 65 Tolstoy got a bicycle from England he spoke of cycling as a kind of “innocent holy foolishness,” which got us to:

who sensing a moment of innocent holy foolishness,

and the next is pure Stuart:

shouted out,

I see we are both not afraid of God!

While I supplied:

The brass band drowned out

the clown’s cry when

according to Stuart:

Tolstoy ran him down, separated him from

the bike, spun it in a circle like a top and somehow climbed aboard,

at which moment everyone and everything hushed, to see what might

ensue. Never to give false promises, Tolstoy whispered to the clown,

It was my turn and after several tries that elicited your Tolstoy: seems too quirky, I remembered Tolstoy believed in non-resistance to evil.

Did not Christ command to use no force against the wicked?

fortunately got nice “turn,” now we’re back on a better track, from Stuart. We ultimately finished the poem, coming up with two different endings. Am fond of both, Stuart said, what thinkest thou: after a loaf of bread & a jug of wine that is…OR we could send both versions out, see what happens…

We sent out one, which Plume accepted.

Stuart’s faith in his own ability as well as in yours and his pleasure not only in his success but in yours made him a beloved teacher and friend.

I hope in the woods where his ashes are finally scattered some wildflowers,

as he imagined, come up on their own thanks to bird-or ant! -providers, he having read that ants are great ‘seeders’ too.

Martha Moody

When I first met Stuart, I was terrified. It was 1973 and as an Oberlin freshman I ended up in a poetry writing workshop with upperclassmen who could pronounce the name Roethke. I loved that workshop—such brilliant, intense people! —but poetry mystified me. I felt like a fraud, and when I eventually met Stuart, the Head of Creative Writing, I could tell he knew this.

I didn’t feel comfortable with Stuart until a couple years later when I started doing poetry translations and met Diane, whose presence I found comforting.

I finished Oberlin and had a talk with Stuart. I told him I was switching to writing fiction. Stuart made a joke about losing me, but I knew he wasn’t serious. About a dreadful boyfriend he made some comment about youth. Those responses were gifts.

I stayed in Ohio, went to med school, got married, went into practice, had four sons. Stuart and I kept in touch. Stuart was a master of emails, all those dearies. My family met Stuart and Diane and liked them. Our third son chose Oberlin as his college to be close to them. Michael did yardwork in exchange for love and food.

Stuart’s fictionalized memoir, The Language of the Enemy, came out after my son finished Oberlin. The book describes Stuart’s time as a Jewish-American exchange student in Germany just after World War II. “Why do you love the language of the enemy?” his grandmother demanded. But in Stuart’s book, there was no enemy. There were people who’d behaved badly and a few who’d been heroic, who suffered varying degrees of loss, remorse, puzzlement, anger, and pride. In Germany, Stuart found real people.

That book made sense of Stuart to me. He liked us. He savored humanity. Of course, he was drawn to translating. To feel closer to the bigger world, my mother invited people from other countries into our house. Stuart invited people to his house of translation: I want to know you! Let me help you spread your beautiful visions!

My first thought after getting Diane’s message about Stuart’s death was How will I tell Michael?

Stuart made me think of a great blue heron—his height and canted-forward posture, his watchfulness, his attachment to fishing. After Stuart died, I delivered to Diane a stained-glass piece Michael had been making for her and Stuart. Diane and I sat in the breezeway with masks on (COVID-19) and she told me that Stuart was alive until he died, curious and joking and wondering out loud about heaven. He didn’t want to end up sick and debilitated. His death was a flying off.

It’s fall now and great blue herons are heading south. In the last week I’ve seen three flying, one by a road, one leaving a pond, and one over my mom’s driveway. Great blue herons are regal in flight but slightly awkward, necks curled up, legs streaming. There he goes, I think, goodbye. See you later.

Marilyn Johnson

Late Messages

He sent photos, jokes, links to poems, prose,

a little bagatelle.

ps in case you’ve not see zissss….

Holler if you DON’T want em (grin)

Slangy, outspoken in a humble way; eager to share good news from friends and loved ones, and generous, so generous. He published me, encouraged me, goaded me.

Yay, you’re VURKING

Hurry with yer new book: am aging FAST!

I did not write fast enough.

It’s uncanny, how his voice comes through in each phrase he wrote, each dashed-off abbreviation. His words and messages so alive, it didn’t matter that I hadn’t seen him in what, forty years?

I wrote to him in June about the new biography of e.e. cummings.

…survived op but died of lack o sleep is where i am,

typin lefty…if i survive have a super eec tale.

Oh nooooo, I wrote immediately. Hang on to that tale….

He did not write back.

I kept an email on my desktop addressed to him, with a link I wanted to share and the start of a note. As long as I keep it open, I can pretend we’re mid-conversation. You don’t take a spirit like his, an insistence like his, and just quit on him.

I haven’t begun to take the measure of what I owe him.

Does anyone know the e.e. cummings story…?

Wayne Miller

Two themes stand out. First: Stuart was an exceptional humanist, full of generosity, empathy, brilliance, and warmth. Second: he was for me (and certainly for so many other students and writers) someone who made essential shifts in my life that altered its course forever.

Three brief examples:

(1) In spring 1994 I visited Oberlin College, where I met with Stuart for half-an-hour in his office in the basement of Rice Hall. I left with several back issues of FIELD magazine (which Stuart had co-founded), a copy of A FIELD Guide to Contemporary Poetry and Poetics (which I couldn’t yet understand), and a surprising certainty that I wanted to study, among other things, poetry, and translation at Oberlin.

(2) About two years later, after a full semester of Stuart reading my underdeveloped poems, I found in my campus mailbox a copy of The Iowa Review with a post-it note in Stuart’s distinctive scrawl: “Here’s someplace you’ll publish one day.”

(3) The following year, Stuart brought in the Albanian poet Moikom Zeqo to visit his class in literary translation. That evening, Stuart invited several students, including me, to dinner with Moikom—who became, like Stuart, an essential friend and mentor, and whose work I’ve been translating for 23 years.

Moikom had been diagnosed with leukemia for some time when, this past June, his health began to decline significantly. Upon hearing the news, Stuart replied that he wished he could share just one more raki with Moikom, as they had done in Oberlin. I suggested that the three of us could have a drink on Skype, and Stuart jumped at the idea. But when I reached out to set it up I learned that Moikom had died suddenly at the hospital. I emailed Stuart and received no reply. They died a week apart.

My next poetry collection is dedicated to Stuart.

It was only upon reading his two memoirs in 2016 that I came to understand more fully what an astonishing act of bravery, forgiveness, and hope it was for Stuart, an American Jew, to have gone to Germany as an exchange student in 1949. And to have done so with an open mind. I can only barely imagine.

Stuart believed deeply—and clearly from a young age—that human beings are fallible and forgivable and full of essential value. I am in awe of his example, and I try (and too often fail) to live up to it.

Chris Santiago

Oberlin is a small town. One sees one’s professors going about their lives. Whenever I did catch a glimpse of Stuart in the wild—which was often—I was struck by how boyish he seemed. This was in the mid- to late-1990s, just before he retired. One summer I rented a house across the street from where he and Diane lived, and set the house on fire (the rented house, not his). As the fire department worked, Stuart came ambling by on his bicycle, screwing his face up at the spectacle but not slowing; he had somewhere to be.

Before Stuart, I wanted only to write novels and stories. Sylvia Watanabe once told me that Stuart snatched my file away so that I’d take his Intermediate Poetry class next instead of Intermediate Fiction. Without Stuart, I never would’ve been a poet. I still remember my first one-on-one meeting with him, in which he paged through the stack of poems I’d sent, and one by one, set each aside and said, gently, “Let it go.”

Until he came to the last poem. To which he said something to the effect of, “Maybe there’s a poem here.” Except the ending. It was a poem about my own father, and how as a child I was mesmerized that he could catch dragonflies with his bare hands, and not only catch them, but let them go a moment later, un-mangled.

But the ending wasn’t right. He handed the poem back to me and told me to revise it. “Good luck with the denouement,” he chuckled good-naturedly. Another time, while exchanging emails after college, he said he looked forward to one day holding a book of mine in his hands. “I hope I get it, ” he joked, “before I catch the cab!” (He was referring of course, half-cheekily and half-morbidly, to Robert Lowell, who famously died in a New York taxi cab.) Some poems of mine had appeared in FIELD, and he had reached out to give both a pat on the back and a nudge forward. That was the kind of mentor he was: devoted, tough, fierce, and self-effacing. He’s left us with a landscape that has his tracks all over it.

Pam Alexander

Poet to the Rescue

The bat must have gotten inside my second-floor Oberlin apartment the same way cold drafts did, through gaps in the old, dried-out siding.

The place didn’t have high ceilings or overhead lighting. Such cave-like conditions were no doubt fine with the bat. But, agitated by the lack of edible, flying insects, it flung itself repeatedly past my face. I knew its famous sonar system would prevent contact but was nevertheless disconcerted to be dived at, collisions averted at the last instant.

“Call Stuart,” Martha Collins said when I phoned her. She and I had come to Oberlin together when Stuart retired. I don’t know how she knew Stuart was the local bat expert and enthusiast, but she was right.

Arriving within minutes, he climbed the stairs with that luminous grin on his face. Bats! He loved them. I would bet he loved any creature you could name. And he loved people. You could read that in his face, too.

He put on a pair of leather gloves—not wimpy garden gloves, or even motorcycle gloves, but the kind you might wear if you wanted to train a hawk to hunt from your arm. They went all the way up to his elbows.

We turned on every available lamp and waited a few minutes for the bat to settle. It crawled to the top of a double-hung window and folded up like a doll-sized umbrella, pressed to the darkness that drew it.

Stuart eased his glove around the bat and held it out toward me. As our three pairs of eyes considered the situation, the look on his face was affectionate.

And then, because he was not one to stand on ceremony, he tossed it gently out the window.

Stuart. Got Things Done.

He founded Oberlin’s Creative Writing Program, for instance, and carried much of its teaching and administrative loads for many years. He founded FIELD and Oberlin College Press with David Young and was an editing mainstay of both. He did all that along with his own work of writing and translating, and he taught with a unique style that students told me was somehow both rigorous and relaxed.

What Martha and I always said about Stuart: it took two people to fill the position when he retired. I was and am grateful that I was one of the two and had the chance to spend some time with this joyful man. His kindness and humor were as legendary as his amazing energy.

Sharon Kubasak

Begin with the birds, I keep telling myself—two birds, a gift from Stuart for my office at Baldwin Wallace. A little chipped, he said, from Italy. Now I like to think his fingerprints are on them.

Stuart and Diane: professors, mentors, friends, second parents. They changed my life. And I became a teacher because of them.

I have been watching the birds more closely since Stuart died: nestling, intimate, trusting in their silence—a prayer, perhaps, a poem.

Two poetry manuscripts in hand, I first met Stuart to discuss Creative Writing at Oberlin. He did not laugh at the pseudonym but said Kubasak was a good name. This gracious restraint left me unprepared for Stuart’s daunting conferencing etiquette. Minimal words were spoken: “Yes” (rare), “No” (frequent), “Save this line” (intermittent). With this Gertrude Stein method of go-figure-it-out-for-yourself assessment, Stuart tested, and he trained. Years later, as outside reader on my dissertation committee, Stuart offered invaluable expertise (even consulting David Young). After the defense, still recovering from a trip, Stuart did not go to The Boardinghouse to celebrate. Instead, once home, he called my mother for a debriefing. Shocked I had not phoned her, Stuart called me at the bar, to tell me to call my mother. Which I did. Of course. Immediately.

In our kitchen, I imagine touching the birds. Picking them up. Holding Stuart’s brilliance, generosity, compassion, encouragement. His belief in me and my work in the intricacy of the feathers.

On vacation, in the Alleghenies, on June 23rd, not knowing he had passed, I was sipping and enjoying Stewart cabernet.

Then, too, re-reading Stuart’s work, I have noticed an observational helplessness. These poems whisper to each other—testaments to private spaces, a translucence of regret—the repeated recognition of what cannot be claimed, what should not be disturbed, what must be let go. And there is beauty in the tenderness that emerges.

Get in and get out, he advised about writing a 500-word review. The birds do not need 500 words to pay proper tribute to Stuart. And they do not need me to touch them.

Stuart did more for me than I could ever do for him. And he has always had my gratitude and love.

In “For Emily, Again,” Stuart quotes a Dickinson letter: “I hope you love birds, too. / It is economical. It saves going / to heaven….” On September 23rd, before leaving for school, I met a little bird standing in our garage. It looked at me, unstartled, gentle, as if to tell me thank you for opening the door. Then it walked out slowly, and then it disappeared.

Deb Bogen

It’s 1969. Stuart’s office is sunk halfway into the earth. It seems small and crowded, oddly sheltering, but this happened 50 years ago. What do I remember — really?

Still, in my mind Stuart is behind his desk looking at a terrified student. Me. An Oberlin outsider who couldn’t have gotten into this place on her own. I’m a “special student,” an exchange crafted by my Pitzer College philosophy teacher and Stuart. Who has graciously agreed to teach me. One on one. For a term. Because I’m having doubts about my philosophy major, maybe, I tell Stuart, I want to write poems.

So, Stuart has assigned something to prod me, to get me to try to write an actual poem. Mythology was part of that assignment (a goddess becoming a tree?) and I’ve tried to write the poem, the first real try that I will show to someone. Lucky me. That someone was Stuart Friebert, eternal encourager, teacher, exemplar, and literary hero.

On the day I’m remembering, or re-inventing, Stuart asked to see the poem, then leaned across the desk and snatched it from my hands. While he read, I tried to breathe. Then he looked up, smiled, swiveled his chair to face his typewriter and slid my poem into the roller. “Hmmm” he said, “I have a couple ideas.”

That sentence characterized the next 50 years of working with Stuart, first in person, later by post, then by email. I’m sorry I didn’t have the good sense to print those emails. Many memories and much wisdom lost to the ether.

But my favorite memory of Stuart has nothing to do with wisdom or generosity or even with poetry. It’s a hot Ohio afternoon. Jim and I have driven to Oberlin to see Diane and Stuart — we’re pretty close so we did that when we could. The four of us spend the afternoon gabbing, driving around Oberlin and surrounds, reliving Jim and Stuart’s and Diane’s early teaching days. We finish up at a lonely ice cream stand complete with picnic tables, blue sky, and an enormous sloping lawn. Jim and Diane wander off to chat, but Stuart and I stake out a table and plop down, licking our melting cones, trying to stop the rivulets from reaching our wrists and elbows. We don’t talk about poets or poems. Or translations. We don’t mention Raeber or Rilke or Celan or Krolow or Günter Eich. We don’t talk reviews or essays, or journals and we don’t go over my new poems, or his. We don’t even talk about Diane’s work, or David Young’s or Franz Wright’s. We just sit together in the big Ohio quiet, eating ice cream.

Dore Kiesselbach

Dear Stuart,

My goal within minutes of meeting you was to become more like you, and I changed my life radically to do so.

As an undergraduate at Oberlin, until we met, I could feel myself being comfortably and well prepared to open a door in the future, a door into the real world. The thought of making poetry had never crossed my mind. But there was a buzz on campus about the writing program you’d founded. A friend urged me to take an introductory class. The story sample I submitted had been handwritten in fifth or sixth grade. That’s where I was on the spectrum of readiness. You accepted me into that intro class perhaps because you knew how rasa my tabula was with respect to your areas of mastery, the most complex and challenging areas in all of letters.

The morning I met you, in Rice Hall, one on one for the first time, is possibly the most re/visited memory of my life. In a world of comfortable distant doors, you stood by an open one that was ready and at hand. The intensity and reality of the energy I could sense, without understanding, on the other side was of a quality unlike anything I’d experienced before, vastly different, and more appealing. At an institution designed to prepare students for the future you stood distinctly—and, for me, magnetically—apart, offering immediate access to the strange exhilarating tumult of the PRESENT, a bold pedagogical strategy that doubled as a moral stance.

Saying that I was instantly transformed by that meeting is not hyperbole. Within days I had mentally walked through that door and have never seriously looked back. Within a year, a straight A student, I’d dropped out of school and was hopping freight trains with Gary Snyder’s The Real Work in my knapsack, a needless flamboyance that you understood well, just as you understood my return.

I learned painfully and slowly, but after more than 35 years, the last 15 distinguished by a buoyant email exchange with you, I write this appreciation knowing, for better and worse, who I am as a writer and a human being in a way that I would not trade for anything on Earth.

At the end of the it day it was not the art you professed in all of its sometimes withering complexity that made the deepest impression on my life, although your technical lessons allowed me to shape a more honest and complete life project than I’d have dreamed of otherwise. No, it was your greatness of character that held and holds the most sway in my development.

Conduct always came first with you. Your dare-devil rectitude was a glorious astonishment to those who knew you, and a mystery that will endure in hearts and minds and on the page for many years to come. Although my conduct cannot match your own, I have become more like you than I ever hoped to be. Thank you.