Philomath

by Devon Walker-Figueroa

Milkweed Editions

paperback 104 pages

ISBN: 978-1-57131-522-9

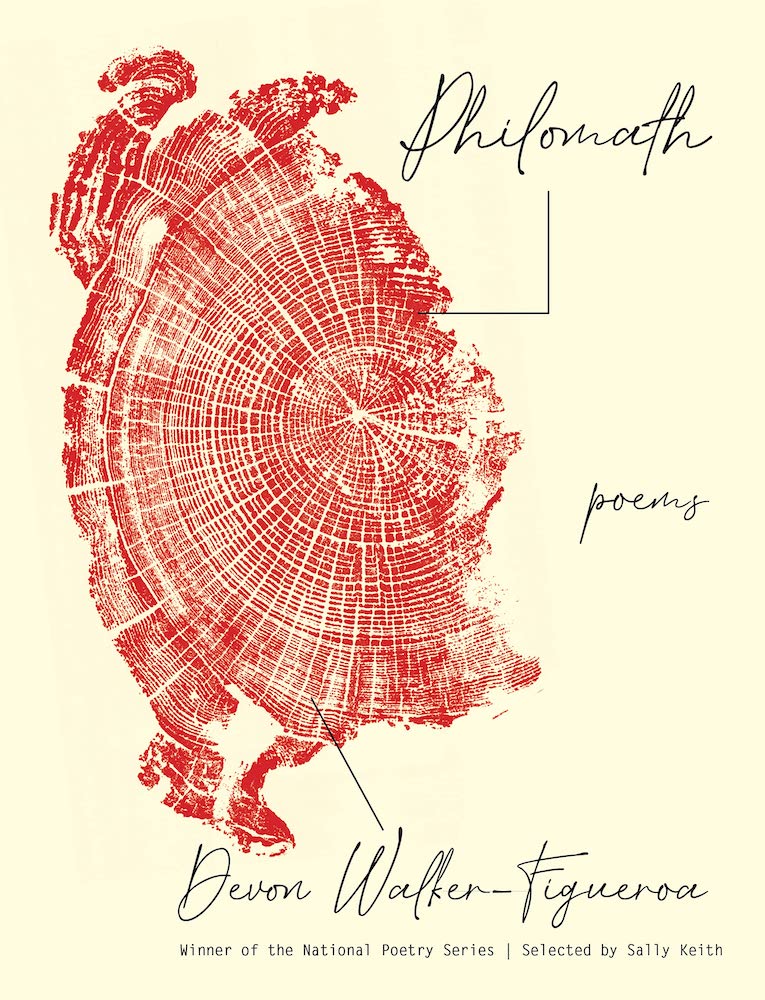

The poems in Philomath, Devon Walker-Figueroa’s 2021 National Poetry Series collection, evoke her origins in western Oregon, a landscape suggested in the cover art by Erik Larson, a stark woodcut of tree rings on a decayed stump. As she revisits the farmlands and vineyards of King’s Valley, “a place known for its dead / settlers & Xmas trees” where there exists an entire cemetery of “land-claimers,” Walker-Figueroa mines bits of her childhood and young adulthood—as an infant listening to “the chirr of locusts, their low- / lying electricity in the field,” a seven-year-old “in the last summer / of the cedars’ lives,” or a young teen who “runs through yellow meadows.” A recurrent theme is the pain of losing her mother. The sequencing of individual poems and the often-fragmented style typify Walker-Figueroa’s process of assemblage, pulling together vivid images of experience like dream shards, powerful and haunting.

The book takes its name from the town of Philomath (which means “love of knowledge”), a place that retains only a ghost of the idealistic nineteenth-century pioneer spirit in which it was founded. In the title poem, which opens the collection, the poet offers glimpses of high school delinquencies and struggles, like her friend Megan, who is beaten by her stepfather and drinks red cough syrup to get high, and the 4-H club members, “who raise up pigs / to pay for college.” The speaker goes to the library, to “check out / A Season in Hell because they don’t / have Illuminations & never will.” Walker-Figueroa, characteristically layering images and references, includes a quote from the Rimbaud as the epigraph of Part II: “Hymns are not allowed here. The air will not hold them.”

Among the place details and childhood memories, the poet-speaker keeps returning to the experience of losing her mother, such as in the three “Out of Body” poems. In the first of these, the speaker’s role is to “keep an eye / on what is left” as her father burns her mother’s possessions after her death. The burning feels like a cremation, and the daughter is physically pulled into the process: “what the air cannot hold / it leaves on the tongue.” The fragmented form of the poem creates a gasping, stuttering narrative mirror. In “Out of Body” #2, “There are times I think I can hold / it inside me forever / this air.” In “Out of Body” #3 the poet declares her physical engagement with her mother’s burned possessions: “all that I did not say remains in my mouth.”

More than half the poems in Philomath spread across the page, leaving gaps of white space like the brokenness of loss, suggesting that the poet is searching for words, and that something always remains unsaid. As in the “Out of Body” poems, with similar formatting, “My Materia” focuses on the disassembling of a life and the reassembly of the pieces, the ultimate task of Philomath. “My Materia” references Umberto Boccioni’s painting of his mother, a kind of broken Madonna. The figure is a patchwork of flat planes, with the hands most prominent, offering a visual challenge like the smoke-blurred images in “Out of Body.” The poet picks up on the Madonna feel of the painting, focusing on her mother’s hands as she prays with her daughters:

she held my hand, my sister’s, we a chain

our murmurations long— a kingdom a kingdom a kingdom become

echolalic sin and syntax refracted as the folded hands in her

favorite oil painting.

The multi-part “Persistence of Vision” begins by retelling the story of the martyr St. Perpetua, then informs the reader that Cape Perpetua, named for the saint, was a favorite lookout of her mother’s. “Perpetua” suggests “perpetual” or “perpetuity” and echoes the “persistence” of the poem’s title, as in enduring. But “persistence of vision” is a specific reference to a characteristic of human sight in which two separate images, a bird and a cage, say, are perceived to fuse into a single image when rapidly alternated. As the poem instructs, this can be demonstrated with a thaumatrope, “stem between the palms,” rubbed together “as furiously as possible.” Was this wishful thinking on the daughter’s part? Walker-Figueroa’s poetic techniques—fragmented text, tight turns, and piled-up images—cannot produce a single, coherent vision of her mother. Rather, “Persistence of Vision” depicts the poet’s mother becoming almost a deity: “My mother’s / fists flew high and at their highest lifting burst / open, released a brief bronze haze of lately-turned / earth.” The poet prepares for another kind of scattering when she addresses her mother’s ashes:

I drive to the lookout you never tired of. Cape Perpetua. The sky

is rare, as in, unburdened of rain, and I

buckle up the bag of you, as if a bad

driver could still disassemble you.

The reader of Philomath experiences the loss of the speaker’s mother, like the geography of western Oregon, in shards and pieces. Late in the collection, in “Beginning Wax to Bronze at Chemeketa Community College,” Walker-Figueroa states plainly that the mother died from a “ruptured heart” in “Good / Samaritan’s Emergency/ Room.” In “Next to Nothing” the poet moves toward elegy with the image of an armchair “that holds the shape of / nobody on earth.” The poet describes her vain attempts to photograph her mother’s hands in the act of playing the piano. Half the images “proved over-/ or double-exposed, the other /half full of hands, uncaptured—all / hyaline.” The double-exposed or blurred photo—like the luminous hands in the foreground of the “My Materia” painting or the burning images in the “Out of Body” poems—suggests one of the collection’s major themes: the struggle to see clearly what is most important.

The poet ends her brave and fragmented story with “Gallowed Be.” With its twisted allusion to the Lord’s Prayer, the title also suggests the fear expressed by Lear’s advisor Kent in Act 3, Scene 2 of King Lear: “The wrathful skies / Gallow the very wanderers of the dark / And make them keep their caves.” Lear is also the source of Walker-Figueroa’s epigraph to Part III. “What are you there? Your names?” spoken by Gloucester who has been blinded, a question that might be asked by the speaker or reader of the poems and events in Philomath.

The rhyme, tight rhythm, and recurrent “no one is to blame” refrain in “Gallowed Be” suggest a hymn or benediction. However, the poem is full of self-deception:

I tell

myself the story that I’ll visit

distant cisterns, let their sallow

walls win me over, lift my low

life & lowly frame of mind.

But the poet loses faith in that story. In the end, when her sister says “this place is lame,” the poet tries responding that “no one is to blame, but the sky is / so hollow it swallows every name.” The stark image of a swallowing sky recalls the rising smoke from “Out of Body” and “Persistence of Vision.” This ending does not forgive or bless. Like Philomath’s other poems, it conveys an overwhelming sense of loss.