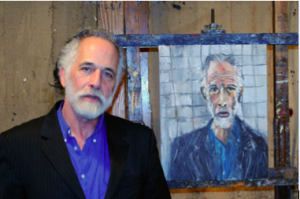

Ira Sadoff with Michael Hafftka painting 2011.

Mitchell: Ira Sadoff, you’re one of American Poetry’s most distinguished senior poets, of whom the esteemed, elder poet Gerald Stern has said, “Nowhere else in American poetry do I come across a passion, a cunning, and a joy greater than his. And a deadly accuracy. I see him as one of the supreme poets of his generation’s culture.” As well, you’re a man of letters whose essays have had a great impact on the culture and conversation in contemporary poetry. You’re been and continue to be a beloved teacher and mentor to generations of now established and aspiring poets. I thought we could chat about the personal and cultural forces which have shaped the trajectory of your career and your poetry.

Sadoff: Well Nancy, I sure am senior. I’m 71. I was born in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn; my parents were second-generation lower middle-class Jews. We moved frequently around the city (which probably contributed to my being something of a loner, often relying on my imagination for companionship). I felt the transiency of friendships, which in my adult life made authentic and loyal friendships both more precious and rare. I ended up in a suburban Long Island high school, Glen Cove, segregated almost as much by class as by race (and like most suburban schools it was motored by cliques, conformity, measuring someone by how he or she dressed or which expressions he or she used). That was probably the first time I felt like an outsider but also, since my father had abandoned our family and we became suddenly impoverished, I came to understand how much class position contributed to confidence and self-worth.

Ira Sadoff: Baseball in the projects 1950

Mitchell: Was there a galvanizing moment in your childhood when you knew you were going to be a writer?

Sadoff: I don’t remember any. As a young person I never felt I wanted to be — or was destined to be — a poet, though one of my neighbors recently reminded me that I showed her poems when I was thirteen. I used to love drawing and was headed to Music and Art when my parents moved out of the city into the suburbs. It wasn’t until my junior year at Cornell when, half-consciously desperate to find a means of personal expression, I took my first poetry workshop. I had no special gifts, had not read any modern poetry (which is where many “gifts” actually come from) except Allen Ginsberg. I was deservedly given virtually no encouragement from my teacher, A.R. Ammons, who was a very good poet but had few skills in teaching the craft of poetry. But writing poems gave me my first real opportunity to feel engaged: I just loved doing it. When told I wasn’t good enough to become a poet I took fiction-writing classes and wrote stories. I then took my MFA at Oregon in fiction writing and published two stories but in the interim had stopped writing poems.

Mitchell: Did you find that same engagement, connection with writing fiction, or was poetry always beckoning?

Sadoff: At the time I really just wanted to be a writer, and if I couldn’t be a poet I still was overjoyed and received enormous pleasure and reward from writing fiction. I remember the precise moment fiction writing caught fire for me in grad. school. I was taking a course in American Lit. from Burt Sabol (who’d recently graduated from the Iowa Writer’s workshop): he generously asked to see a story of mine. In conference he went over the story line by line, not only editing but also showing me the power of timing – missed opportunities, moments where I could dig in deeper or moments when I had talked my way out of a scene. I’ve carried this knowledge with me my whole writing life.

I continued to write and publish fiction until I was fifty and I could see the imaginative limits of the work: my almost involuntary fidelity to autobiography, a cautiousness – based on the myth that sincerity and an allegiance to subject matter had the highest priority – proved to limit my artistry as a fiction writer. I wrote and published a novel when I was thirty and it was my transposed personal story. I kept trying and failing to write another novel but the work wasn’t compelling enough to complete even a draft. I couldn’t find my way out of this dilemma in stories either so I put my prose energy into writing essays.

Mitchell: When did you begin to write poetry seriously?

Sadoff: During my first teaching job at Hobart and William Smith when I was twenty-two. My colleague, Jim Crenner, became my first real teacher (and virtually the first poet I’d met).

When I shyly showed him a poem I had written, he said this work’s strong because… this writing is weak because… now read these writers. He was so generous, reading many a poem of mine, and soon I was absolutely driven by passion for the art. In my own autodidact way I started reading everything, catching up. Good writing then no longer seemed like a gift from the Gods but an attentive laboring. Every day I woke up at five in the the morning to write for four hours before teaching.

Mitchell: Ah, Jim’s Crenner’s generosity changed your life. You were so lucky!

Sadoff: I absolutely was and I’ve always aspired to bring that generosity and rigor to my teaching. I know how much it means to be taken seriously. That’s also why I’ll never make judgments about “talent” in a young poet. There’s almost no way to know.

Mitchell: What was it about writing poems rather than fiction that made it a more fulfilling means of expression, your art of choice?

Sadoff: The short answer: I had access to my imagination and the joy of play. Working by association I felt both a sense of freedom and discovery. I could become a better listener to suggestion. I hope this skill has translated to a strategy of my poems would be the arbiter of what I actually rather than willfully felt. I also loved the joy of shaping a poem: I could see how the process was sculptural rather than intellectual and it suited my tactile temperament.

Mitchell: Were you lucky enough to have encouragement from and influential friendships with other poets as you were starting out?

Sadoff: I had some early encouragement from literary magazines but other than that I was a kind of self-made poet. While at Hobart — this was in 1969 I think — Jim and I started THE SENECA REVIEW, and then I started corresponding with other poets, learning my craft because I had to make judgments. I began developing some poetry friendships, Charlie Simic and Phil Levine among those who became lifetime friends.

Mitchell: How nourishing for a young poet to be in conversation, develop friendships with established poets, and be in close, daily proximity to the poetry hum, via teaching and editing THE SENECA REVIEW.

Sadoff: Retrospectively I feel very fortunate to have grown up during a prosperous time (assuming you were white and middle-class). I didn’t worry about making a living, just finding meaningful work. It was a time when counter-cultural values were ascendant and becoming a poet seemed like one plausible way to change consciousness.

Mitchell: So, making art at that time was both a personal and conscious political act?

Sadoff: Yes. The poetry I admire most questions authority and convention, attempts to integrate or wrestle with the fissures between private and public life: it’s what Blake called Vision. Periodically in American Poetry, you’ll find the dominant aesthetic a private or transcendent poetry, mostly written by white middle-class people who have the luxury to feel insulated from the forces that shape them, their values and their art. But I started writing during a bold and exciting moment in American poetry and history: the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, the second wave of feminism, all pressurized our views of experience and the function of poetry. The Sixties brought doubt to our unbridled belief in reason and the Enlightenment Project, in the American Dream, in universals, in the absolute wisdom of the fathers. Our philosophers were Nietzsche, early Freud and Heisenberg, those who recognized the force of subjectivity, desire and entropy

Mitchell: What an incredibly dynamic era to be coming of age, and into one’s art; seismic shifts which artists were struggling to find forms with which to express them.

Sadoff: The dry rhetorical academic poetry of the Fifties was dying out; we discovered what would later be called the new Internationalism – recognition of the great poetry written and translated from other languages. The most influential poets were Neruda, Lorca and Vallejo, Rilke, Ritsos, Trakl, Apollinaire, Desnos, and Eluard, Transtromer, Popa, the post-War Polish poets like Herbert and Milosz. Robert Bly’s THE SIXTIES and George Hitchcock’s KAYAK made many of these poets widely available for the first time.

The often willfully naïve and transcendent view that politics belonged to sociology and not our daily experience was exploded by poets like Neruda and Bly, James Wright, Adrienne Rich, Charles Simic, W.S. Merwin, James Tate, and many others – after all, we had an immoral war to face, the destruction of our cities, the more visible oppression of minorities, the oppression of women in the workplace, the kitchen and the bedroom. These poets modeled for my generation of writers a new and necessary way of speaking.

Mitchell: And to think that those revolutionary poets are now established in the canon of contemporary poetry; we owe so much to your generation for radically enlarging the frame of reference, the consciousness, and aesthetics of poetry.

Sadoff: Their poems were mostly characterized by a faith in the image (sometimes called the deep image) and surprising metaphors and juxtapositions, in embodiment, in the irrational and the dream life (hence the neo-surrealist movement), a return to the “direct treatment” of the thing, to poems that didn’t gloss their own meaning. I wouldn’t personally take credit for this change but I was happy to participate in the shifts: they were enormously important to my development as poet and person.

Mitchell: How were your poems using the deep image?

Sadoff: Perhaps “Disease of the Eye” from my first book, SETTLING DOWN, was the earliest example of the kind of neo-surrealist influence I can think of:

DISEASE OF THE EYE

Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night,

in the middle of my own house, to discover

some woman has had her clothes in my closet

for years. She has even slept in my bed.

I feel like a child in an old movie,

asking myself where have I been. A film

covers the eye, and I can only recount events

out of sequence, in a haze. This is not clear

enough. It is as though I were a doctor

looking into my eyes with a strange

light, chasing the pupil into an endless tunnel

which is not endless. The pupil shrinks

like a schoolchild who does not know

the answer. I demand to know everything

below the skin. Who’s the stranger sleeping

in my hands? What does a wife mean at night?

Something strange is going on

in my bed. I ask my wife, “Who is this man

you married?” She answers, “He has eyes that run

behind the lid.” For this ailment

the doctor recommends the following:

cover the eyes with a cold compress of hands.

The stranger will disappear. The lights

will dim, but you’ll know where you have been.

Mitchell: Surreal indeed-it’s a conversation between the selves, the layers of consciousness via the mediating the image, isn’t it? Do you agree that this consciousness of the selves within the self has been a consistent characteristic in your poetry?

Sadoff: Absolutely. I’m really interested, and suppose I’ve always been more interested, in asking more questions of a poem and its competing feelings than dispensing wisdom or solving problems. To think of poems with an arrival point is to reduce experience. What a revelation to know that we have many feelings at once. That poem knew more about me then – I was twenty-three I think – than I did. Which is, I guess, how it should be in poems. For me these imagistic poems helped me mediate a controlling intellect. The aspiration of those influential poets was to embody, to acknowledge feeling precedes knowing, and to incorporate what we called the “darkness” (a shortcut for mystery, the irrational, and the unknown).

Mitchell: Yes…in the same way imagery in surrealistic paintings disables the mind by refusing a reference or representation on the conscious level. How did this exploration change the shape of the poem on the page?

Sadoff: Formally this verse solidified the trend toward free verse and away from received forms; it often moved away from traditional punctuation, toward fracturing the line through line break, and suggesting more open-ended closures. We were critical of the ideology of new criticism’s faith in paradox and transcendence (which we saw as serving the soul over the body, “organic” unity over complication).

Mitchell: Yes, there was a longing for a Whitmanian wholeness, an organic connection, to “the starry dynamo.”

Sadoff: Right. The “truth of experience,” and finding a language and form that would reflect the breaking of artifice and boundaries. Further, there was a movement toward more direct speech using more fissures in syntax, extending the line. Also we refused the strategy of emphasizing the more obvious, clangy surfaces of alliteration and onomatopoeia, the ornate diction that had made poetry seem decorative or “pretty.” In subject matter we saw a turn toward the erotic, toward acknowledging an untamed interior life, but paradoxically also a turn toward the social.

Mitchell: Maybe there was a sense of a shared interior life…a shared consciousness? How did your own poems track these changes?

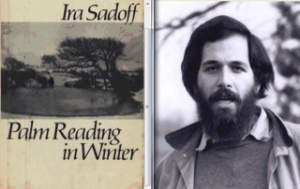

Sadoff: Again retrospectively I can see the first stylistic changes in my work came with the second book, PALM READING IN WINTER (just reissued by Carnegie-Mellon as part of their American Classics Series). Jon Anderson’s IN SEPIA literally changed my life. I was so moved by the intelligence of the poems, the austerity and music, I wrote a long review for SENECA. I was teaching at Antioch College at the time and Jon thought I’d so captured his aspirations that he decided he and his wife and child and dog would come visit me for a week. It was a wonderful, eye-opening week, and it served as one of my first deep friendships with another poet. It allowed me to put more conviction in my poetry. That’s when I wrote more direct poems like “My Father’s Leaving,” and “Depression Beginning in 1956.”

MY FATHER’S LEAVING

When I came back, he was gone.

My mother was in the bathroom

crying, my sister in her crib

restless but asleep. The sun

was shining in the bay window,

the grass had not been cut.

No one mentioned the other woman,

nights he spent in that stranger’s house.

I sat at my desk and wrote him a note.

When my mother saw his name on the sheet

of paper, she asked me to leave the house.

When she spoke, her voice was like a whisper

to someone else, her hand a weight

on my arm I could not feel.

In the evening, though, I opened the door

and saw a thousand houses just like ours.

I thought I was the one who was leaving,

and behind me I heard my mother’s voice

asking me to stay. But I was thirteen

and wishing I were a man I listened

to no one, and no words from a woman

I loved were strong enough to make me stop.

Mitchell: I’ve loved this poem for a long time … the static images, frozen in memory “The sun/was shining in the bay window,/ the grass had not been cut.” …the precision with which the mind etches, documents shock to distance from it. It seems out of this moment is a burgeoning awareness of the selves within the self which I mentioned as a characteristic of your work. “But I was thirteen/and wishing I were a man I listened/”… so beautifully vulnerable.

Sadoff: Thank you Nancy.

Larry Levis, 1979 Aspen writer’s conference

Photo by Kurt Brown

Mitchell: Would you go so far as to say that this poem was a “threshold” poem, “I opened the door” which lead to other changes?

Sadoff: For a while, Yes. Actually I’d written many poems about my father’s leaving before then and Greg Orr suggested why don’t I just let the camera roll on the event without commentary? That helped me really live inside that moment. In the closure I coupled that strategy with a conviction based on what dramatic evidence the poem had provided me.

I’d say the next most dramatic change in my poems came during the time I was writing GRAZING. I consider the poems in that volume the most adventurous I’ve written, breaking the fourth wall, using collage, interrupting sentences, fragmenting narrative, using more fissures in syntax. Also extending the range of emotions I could use within a poem, which I would call a kind of wildness. At the time I was reading the language poets and though it may be difficult to see the influence in the work, I was challenged and nourished by poets like Lyn Hejinian in her MY LIFE. I began thinking more about the urgency of associative thinking in poetry, and realized my feelings grew out of a lifetime love and appreciation of jazz: the syntactical response to what’s already in the air or on the page, and then following it both through improvisation and the memory of what you’ve heard. I’ve written, for the AMERICAN POETRY BLOG, a blog entry about it: http://blog.bestamericanpoetry.com/the_best_american_poetry/2012/09/mr-pc-imagination-and-improvisation.html

Mitchell: Can you give an example of how this works in jazz?

Sadoff: Yes; David Murray’s DEEP RIVER riffs off a John Coltrane tune, MR. PC (PC is for Paul Chambers). If you listen to the Coltrane first https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jv5j_Lx2R4g. you’ll hear the improvision on Murray’s DEEP RIVER: https://www.song365.name/track/david-murray-mr.-p.c.-268584.htm

Mitchell: Whoa! I can hear those connections!

Sadoff: Murray didn’t exactly make this adventurous Coltrane cut sound tame, but Murray took the changes and created endless melodic invention from them, varying speed and rhythm with an almost manic propulsiveness. While writing poems during this period I not only began to trust the language in the poems but I was able, in the best of them anyway, to write more associatively, a little more wildly, and to forefront the medium the way a painter would make use of paint. After all, an audience is moved – that is to say changed – by the words we use, how they’re arranged on the page.

WHEN I COME HOME

after the Xenia tornado of 1974

In Cincinnati the river is the color of nausea,

and in Xenia the tops of houses

have been taken off and rest in the river.

When I come home and she’s not home,

the worry thickens, I think she must be sick

not to want me. I still have a picture

of that naked girl on fire in My Lei,

her arms high in the air, her hands

screaming, and behind her, her mother

waving a handkerchief on a stick. And behind them

the whole village running from their village,

napalm scorching their thatched huts to slag.

Xenia means friendship. Xenia means flower.

See what a name means.

To be afraid of Xenia is to be afraid of the other.

The sky is mud and thunder. The air is green,

thick with pollen, my wife and I swing on a porch swing,

listening to the frogs and crickets, thinking,

The elm tree is a thing of beauty. The elm tree’s actually an oak,

but we can hear the stream unfurling.

We enjoy the wetness of it. The essence of it, dripping.

We are only twenty-one and twenty-two, singing.

I still have a picture of her, her arm

wrapped around my arm, her lips on my neck, pursed.

When I come home and she’s not home,

the story of the world is not of interest. I am

speechless, going back there, to the four room cabin

in the dense Ohio wood, still further back,

waiting to disappoint, failing to predict how to soothe.

The sick are nothing but plasma, whereas the healthy

play the saxophone and saturate the river.

The world is not as heavy as the door to my room, open.

She lost her wedding ring in the crack beneath the buckled floor,

so she’s free. I think about fire dropped on a child,

the funnel spinning, coming closer, the sky white as knuckles,

a snow of splinters, how I’m behind the couch, waiting.

I can feel the blood rush in and my skin on fire.

To listen to my heart, you’d think we’d seized it, the music,

the state called rapture. Where the river runs in summer,

nothing but a few flies and stones to disturb it. The two of us

sitting and listening, unprepared for what comes next.

This is only a story, so I can say what I want. I can hold back

the ending for a moment, when I come home from school,

when we call out, when the bloody soldier burns away

attention span, when a helicopter wheels him off to heaven.

Mitchell: Yes; I can see how jazz influenced the leaps, empathetic connections via imagery between the self and others and the parallels of the private and larger worlds blown-to-bits:

I think about fire dropped on a child,

the funnel spinning, coming closer, the sky white as knuckles,

a snow of splinters, how I’m behind the couch, waiting.

I can feel the blood rush in and my skin on fire.

This must have been a thrilling, liberating poem to write.

Sadoff: It took a long time to take out ritualized writing and responses, to let the leaps stand, but yes, I knew after I’d written it that the poem had advanced my work. At this time I also became impatient with poems dictated by subject or narrative poems dictated by chronology: most of them seemed willful and predictable. You knew as much at the beginning of the poem as you did at the end. I began to feel, and still feel though I rarely execute it, that if you’re writing poems you’re using a very particular medium and that part of your job as an artist is to advance the medium beyond a priori conventions. It just makes sense that when you think of Pound’s “make it new” he’s embracing the way the Modernists changed poetry, the way we write and think about it. In my view we should still be doing that.

Mitchell: Wasn’t it about this time that the neo-formalist backlash to this kind artistic adventuring reared its head? A backlash that you so boldly challenged in your essay, “Neo-Formalism: A Dangerous Nostalgia” which essentially split the American Poetry scene into two camps … a civil war of sorts, a glorious ruckus, a huge, passionate controversy.

Sadoff: Yes, though I think that poem was written a couple of years before the essay. Sometimes I’m a little too passionate about the art for my own good. I remember reading Foucault and Derrida in the late eighties: their work reinforced my understanding of the contexts of poetry. The art’s never written in a vacuum: it’s no accident that the Romantics’ obsession with the self and subjectivity occurred during the beginnings of the industrial revolution: institutions, church and state, failed to reflect the needs and values of the culture. So here we were during the Reagan administration, the AIDS crisis, a time of terrible entropy; it’s in this context that Conservatives fought on so many fronts to try to retrieve concepts of universality, patriarchy, and the nuclear family. You saw the ideology reflected in Christopher Lasch’s attempt to rescue patriarchy in THE CULTURE OF NARCISSISM, in films, the neo-classical movement in painting, and of course in poetry.

Someone then sent me a review copy of Robert Richman’s THE DIRECTION IN POETRY. Of course the poems were terrible, nostalgic in subject matter and almost fascistic in the editor’s insistence on singsong meter. It was the artistic equivalent of suggesting that we compose music as Bach did, with the same harmonic limitations. Or that we compose in sonata form. But music’s everywhere in our speech, it’s multi-cultural in every sense: our meters are variable, not anarchic, but in varying meters the music does grow out of our improvisations and associations. If you can’t hear different musics in John Ashbery’s poems, by example, (he uses various rhythm structures and levels of diction to create those cadences and competing stances) you’re not listening carefully enough. And my own opinion is that we’d have a lot of difficulty naming many great poems written now in fixed forms. The last great formal poet was Elizabeth Bishop, and with the exception of “One Art,” her greatest poems are the late ones written in free verse. I think the pre-modernist cliché (perpetuated by Frost) that writing in fixed form liberates content is mostly nonsense, one that’s perpetuated by exercises in writing workshops to this day. Or, ok, maybe not complete nonsense but rather it’s true in a limited and pretty desiccated way: that counterpoint worked for Mozart, where the steady left hand created tension with the freedom of the right hand. But it was an Enlightenment idea and doesn’t really apply to the multiplicities of rhythms we experience in our music and speech today.

Anyway when I sent the essay to APR (a magazine that’s been very generous over the years in giving me a platform for my views) I knew it would be provocative and I expected it to be met by some challenges. I didn’t expect it to have the lasting effect it apparently has – both negatively and positively – but the essay, substantively re-written in HISTORY MATTERS, still basically reflects my views, not only about poetry but the oblique but inescapable relationship between poetry and culture.

On principle I’ve tried not to be political (with a small p) in anything I write, which is to say worrying about whether people would be angered or approve of what I say. I’ve made a lot of enemies and I’m not proud of that, though most of my critical work sings the praises of poets I love. We know that in private most poets are much more free and authentic about what they feel about other poets, but people worry about how saying x and y might affect their “careers” or, more honorably, affect their friendships. So we get reviews of friends reviewing friends, writers inviting readers to their campuses as a commodity exchange.

Mitchell: You bring up a good point. I wonder to what extent “career” considerations have impacted poetry itself, especially as creative writing programs have been assimilated into academia. Most university teaching positions require publication, an MFA plus a PhD, and the track to tenure can be slippery if one doesn’t mind their political manners. Maybe “making it new” and being authentic is too risky?

Sadoff: The whole MFA question has been batted around a lot. I think because writing, like painting, is a mentoring art (a good writer/critic can save a writer time and put some important questions in a students’ head) grad. programs can help one become a better, more ambitious artist. The dangers of these programs are pretty well known: consensus workshopping and the desire to please authority can certainly dampen adventurousness in the writing process. It’s also true that when teaching steers toward mechanics, separating the craft from the art the result is an empty well-made exercise. The larger issue for me is the kind of careerism some programs engender, encouraging students to send out their poems, publish books, establish their own presses before the students learn the art. Beyond the economics of the academy, encouraging that kind of worldly ambition is all about a hunger for fame and recognition. That’s a cultural problem and speaks to the emptiness of American life, its self-absorption and celebrity culture.

Mitchell: Ah, sadly, yes. Do you address this emptiness in any of your recent poems?

Sadoff: Yes, not intentionally, but the subject comes up. Sometimes you’ll see it in the desire for community, sometimes feeling melancholy or envy for those who belong, sometimes receiving real pleasure from the solitude. “I Never Needed Things,” a poem I recently published in THE NEW YORKER reflects all of those feelings.

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/02/29/i-never-needed-things

(Readers can also hear Ira read the poem aloud on the NEW YORKER website.)

Mitchell: That’s a terrific poem. Ira, you’ve been so generous to share some of your newer poems with Plume; again, thank you. I love these poems, and in them I see the characteristic “energetic syntax and the astonishing range of idiom and tone,” which Alan Shapiro has praised, as well the “unpredictable weaving together of individual and collective life, the insightful, almost seamless integration of personal experience in all its unredemptive anguish with the heterogeneous realities of American culture.” What do you perceive as the most significant shifts in these new poems?

Sadoff: In my most recent poems, though they seem to be more representational, I still try my best of follow the language: I begin with a line or an image and then ask what’s next. I try to ask as many questions of a poem as I can, not to close it off before the most difficult and urgent questions posed have been advanced. I look for opportunities for disruptions. They often serve as metaphorical episodes that I hope intensify the poem’s progress. And ultimately that’s what I’m after in poems – intensification. To feel fully, to inhabit, to move beyond the narrow confines of the self, but not to solve or advise, and certainly not to re-write what I’ve already written. In the present tense, though you might not know it from the above comments, I try not to be too self-conscious about what I’m doing. Though I’d like the poems to continue to be adventurous I’m obliged to follow the poems where they authentically take me. I always want to honor authenticity, which includes the shifting and partial selves we inhabit, so that the poems display some inner necessity, poems that really need to be written.

Mitchell: You know, these new poems are intriguing, paradoxical; although they’re maybe more representational/narrative than your earlier poems, they lead us into darker terrain. And because you try to “ask as many questions of a poem as I can, not to close it off before the most difficult and urgent questions posed have been advanced” the poems reveal their mysteries. For instance, in “Wilderness” (below) we follow the speaker into

this great wilderness, a snow-patched meadow

above the tree line — the air so thin

hiking left me out of breath

in this green, unkempt site just off the map

which is linear enough until “just off the map” alerts us that we have left the beaten narrative path and find ourselves observing a “fangle” = fantasy + tangle of almost mythic/primordial beasts. Here, in a reversal of the Darwinian sequence of reptilian-to mammalian evolution, it’s the surfacing reptiles which scare off the warm-bloods. (Why do I see Bly’s face here?) It seems that in the speaker’s immersion in the moment references to the self-in-context begin to blur.

I couldn’t tell you where I was

or how I landed somewhere glorious: I can’t describe

the jumble of sensations, the dizzying changes

in the light, clouds appearing, passing, and shading

the muffled ball of sun.

For a moment the speaker is suspended on the precarious brink of transcendental dissolution, pulls back in a flash of self-awareness: “I didn’t think I could take this in, / how it all just came to me, slid into my horizon.” The speaker struggles to believe that grace is given, not earned by personal suffering: “Was this scene more precious because/of what I’d brought with me, years of wanting, striving-for what-all those years with holes in them?” Even if he could accept an unconditional “amazing grace’ he cannot, because to do so would leave the “others” behind.

my friends from Bensonhurst: strap marks on their flanks,

knife fights on the buses, break-ins, little balls of white bread

they considered breakfast, the whispers

behind their backs: What imbeciles you are. Where’s their gift?

Whether the “I can’t forget” is the self-admonishment of “you musn’t forget,” or the speaker’s inability to forget is moot; he cannot forget. And the speaker, in a stunning acceptance and integration of “the shifting and partial selves we inhabit,” surrenders to the knowledge that grace and its attendant bliss, whether given or earned, will never absolve him of the responsibility incumbent upon him witness for those who are “still waiting for it.” A modern day Moses, he returns from the mountaintop to “drive back home to a more familiar wilderness:/ my cluttered desk, street noise, all those voices calling.”

Sadoff: Thank you Nancy. You’ve taught me something about that poem and its ambitions and the function of memory in my work as bringing me back to community. Memory can serve to connect us with other humans by making us more empathetic, or it can paralyze us and make us feel overwhelmed. I think in that poem both those feelings surface.

Mitchell: In the poems “Between Shifts” and “SHHH!” the speaker’s tone is that of an understanding, wiser self, who is, if not ready to forgive the younger self for fuck-ups, then will make allowances. The speaker acknowledges that these blind missteps were committed in innocence, under the barometric pressures of personal history, under the cloud of “before the fall” which looms darkly in the future. I don’t want to spoil our readers’ pleasure by the same degree of analysis with which I indulged myself with in “Wilderness,” but would you say that this is a relatively new tone, one that has been developing over the past years?

Sadoff: Oh Nancy I’m not so sure. I know it comes up more often these days. I suspect these changes in the work reflect changes in the life: growing older, looking back, seeing that younger self wrestle somewhat blindly, or at least incompletely, with some of life’s struggles. Now that I think about it, I seem to almost want to guide that self through the labyrinth of difficulties, navigate with, as you say, generosity and honesty. To be as honest as one can be with oneself.

Mitchell: The penultimate poem in this sequence, the exquisitely haunted “Chambermaid” inhabits and moves “beyond the narrow confines of the self.” The intention of the final poem “A Moment’s Calm” is announced by the epigram by Primo Levi, and posits a tentative acceptance of a self in which the “fangle” of selves tangle. Yet, maybe at the same time there is a ruefulness that this grace, which has been hard earned by living squarely in this life, comes a little belatedly?

Sadoff: Maybe more “rhomboidly” than squarely, but thanks. I wish I’d seen more, known more, on some occasions acted on desires, on others made a few different choices. I don’t see how anyone lives a long life without some moments of regret. So yes, rueful, but that’s only one part of the story. I know I’ve had many opportunities, have been blessed to have this work, to be granted the teaching life (I’ve had so many wonderful students, poets and non-poets, who’ve become life-long friends), to have loved and been deeply loved, and to have been given the gift of resilience, which has allowed me to bounce back – or sometimes limp – from adversity. I think what I’ve gained from a lifelong commitment to poetry is a kind of attentiveness, a capacity to listen better, to hear suggestion in someone’s voice, to continue to be, imperfectly, open-hearted. To match the words with the life, that’s one of the great things writing poetry can do.

Mitchell: Ira, it has been an incredible pleasure. Readers, go get your headphones, and enjoy this rare treat.

WILDERNESS

Just yesterday, when I came upon

this great wilderness, a snow-patched meadow

above the tree line — the air so thin

hiking left me out of breath

in this green, unkempt site just off the map

I was reading — I saw a pond

with moose, cows and bulls in a fangle

slurping at its edge until some sound stirred them,

and how clumsy and rushed their exit

before some reptiles surfaced from the water.

I couldn’t tell you where I was

or how I landed somewhere glorious: I can’t describe

the jumble of sensations, the dizzying changes

in the light, clouds appearing, passing, and shading

the muffled ball of sun. I didn’t think I could take this in,

how it all just came to me, slid into my horizon.

Was this scene more precious because

of what I’d brought with me, years of wanting, striving –

for what? – all those years with holes in them? I can’t forget

my friends from Bensonhurst: strap marks on their flanks,

knife fights on the buses, break-ins, little balls of white bread

they considered breakfast, the whispers

behind their backs: What imbeciles you are. Where’s their gift?

They’re still waiting for it. And what does it all add up to,

my being here, sitting on some granite as the sky darkens?

It’s night, noiseless, the moon shines on the snow patches,

there’s a nudge of wind. I wish the pond were a sea, I wish

my friend John were still here, I wish I could keep this day

in parenthesis, but I can’t, so I hike to my car

and drive back home to a more familiar wilderness:

my cluttered desk, street noise, all those voices calling.

BETWEEN SHIFTS

Jesus and I were flipping channels,

mocking TV preachers’ mania for money

and sin: we were high on something,

but when it came to the aura

around the set — and there was light –

we saw things differently. This before

the ruined motels of the Catskills

littered the hillsides of upstate New York.

I hadn’t been there for the Robeson concert

but uncle Max had come back to the city

bandaged up in his bashed-in Chevy wagon.

I remember too when Jews were barred

from hotels elsewhere, how we paraded

around the Catskills, playing cards

but mostly trying to act like Christians.

I suppose we drank gin and wore ties and jackets.

We didn’t really know any Christians. Which is why

it was so funny hanging out with this Jesus

who was half Puerto Rican, a hundred percent Catholic.

This Jesus had come back from the War scarred:

my ancestors, he’d said, had murdered him.

Otherwise what were the nails for, the needles?

I don’t know who swung first,

and maybe there was light on the floor

where we wrestled for some purpose kept from us,

but when we surfaced, bloodied and dazed

there was our boss at the door, calling us back

to bus our tables, and beyond him

early morning light seemed to pry open

the fingers of the branches: for a little while more

we could retreat to our separate Gods.

SHHHH!

We walked in the woods, like Dimmesdale and Hester,

only back then I didn’t give a shit about literature:

there was this woman who adored me:

probably she didn’t know me, she confused me

with some antidote to her self-absorbed boyfriend.

Maybe she saw the two of us as the same person.

Later she’d join some sexless sect that wore white robes

and burned incense — she was rightfully earnest about it all,

because we were both lost: I had a shitty marriage

I couldn’t mention or think about.

Everybody I knew was careless or reckless as I was,

from the drugs we took to the curves we took

in the dark, and short of being saved

sex gave us the kind of oblivion we deserved.

And I should never say this, I remember her breasts exactly,

and her round face and her curly hair

and her conversation, some exact phrases: we told secrets here,

we groused, we knew no one cared about us,

we had nothing to offer, so let me open up the world

a little more because this is getting claustrophobic:

we’d invaded another tiny country:

who could bear enemies so close? The Clintons

were locking up the poor, and in spite of all her humiliation,

Hillary stood up for the Defense of Marriage Act.

That’s all I knew and I could get agitated about it, but the point is

we were sitting on a log by a stream, no one saw us,

we could have kept on going to a deeper and darker place –

but I suppressed the urge to tell my wife

I wanted to start over before it was too late,

because it was too already too late to describe

the disdain we felt for each other, how we found more

and more irritating every sentence the other spoke,

so I shut my mouth as I almost always did

back then, cooked a meal I can’t remember and slept

in the marriage bed a few years more.

CHAMBERMAID

As a child I was a chambermaid,

bent over, picking up after, doubling as a cook –

better the kitchen than the bedroom — stirring the caldron

so volcanoes bubbled up and sprayed the kitchen walls

with the graffiti of green pea soup.

Sent to my quarters

I fumed like an orphan in literature, or more

like an infant, irritable and colic. But while in lockdown,

labial forces were set in motion: not the usual

shame and silence, but plots to set the palace ablaze.

Being a man then

would be like being a particle of soot

from an old incinerator, circa 1955. But this hasn’t happened yet,

so we cocks-of-the-walk can rest easy now, light up

at a café on the left bank and discuss

our favorite subjects, from Spinoza to sacred texts

like The Odyssey, where fathers pack a suitcase

and disappear when children must be fed.

I waved goodbye to one from the harbor.

And searched for him with my lantern

in neighborhoods where no one would want to be seen.

But since I spent my childhood as a chambermaid,

I know that place where you knock on doors

and no one answers.

And what comes next: cleaning up

their rooms, emptying out the wish bin

or something more fulsome I’m crossing out, trying to imagine.

A MOMENT’S CALM

“I live in my house as I live inside my skin: I know more beautiful, more ample, more sturdy and more picturesque skins: but it would seem to me unnatural to exchange them for mine.” — Primo Levi

Now for a moment’s calm. Maybe it will go on

and on, like a Strindberg play,

or it could be brief, shockingly brief, like a life.

Maybe I’ve been waiting my whole life for this.

What I call waiting is settling into a barn

with a ceiling fan to circulate the heated air,

wood beams from another century. In this stillness

I’m not disposed to making corrections.

I’m at peace with your happiness even if you’re gone,

invisible, even if we fought over the fate of the universe.

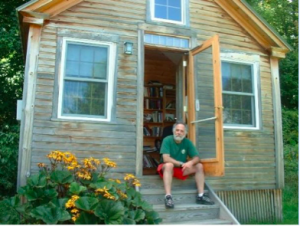

Ira Sadoff at Maine Writing Studio composing poems for TRUE FAITH 2008

Ira Sadoff with Jerry Stern, at the Fishhouse, 2003

Ira Sadoff’s the author of seven collections of poetry, most recently TRUE FAITH (BOA Editions, 2012) and the re-issued PALM READING IN WINTER (Carnegie-Mellon). He’s published a novel, UNCOUPLING, THE IRA SADOFF READER, and HISTORY MATTERS U.of Iowa Press) a critical book on poetry and culture. He’s been widely anthologized and awarded grants from the Guggenheim Fellowship and the NEA. He has new work appearing in THE NEW YORKER, APR, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem a Day Series. He lives in a converted barn in upstate New York.