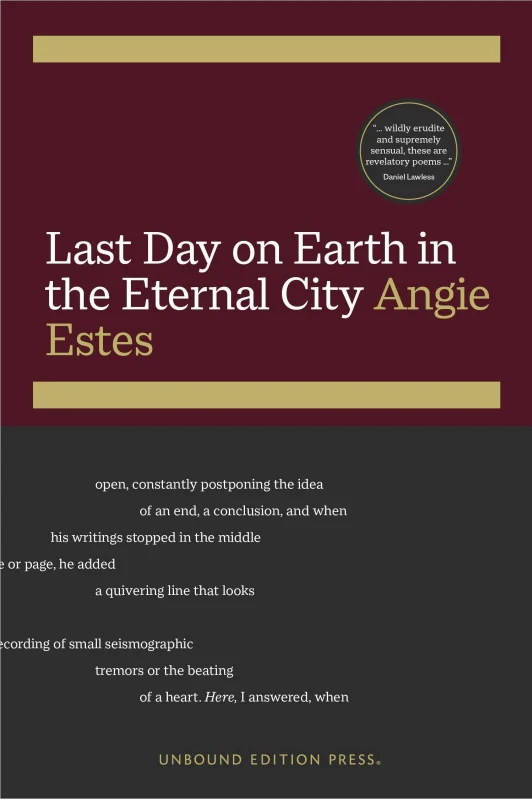

Angie Estes, Last Day on Earth in the Eternal City.

Unbound Edition Press. April 2025.

Reviewed by Jane Zwart.

Chances are that you don’t need Angie Estes to tell you that our experience of time is a hotbed for paradox: that a life of ordinary duration will feel sometimes too short and sometimes interminable and that our ghosts trespass, stealing into the present from the past. But to call something a paradox—the workings of time, say, or the absent presences and present absences of our dead—can be either to shrug or to marvel. I’m convinced that, mostly, we’re better off marveling, though to marvel comes less naturally than to shrug. Not to worry: chances are Estes’s latest collection of verse, Last Day on Earth in the Eternal City, will nudge you, as it did me, in the direction of awe.

In order to set you marveling firsthand, though, Last Day on Earth must also lay some groundwork. Thus, it sometimes announces its paradoxes, as is plainly the case in these lines from a poem named “Spring”: “Faulkner was right when he said / the past is never dead; it’s not even / past.”

But this poem, like the collection as a whole, does not merely name the hologrammatic relationship of the past and present. It also enacts it. The poem, to begin, describes spring as “in such a / hurry,” noting the uneven pace of the seasons, the hasty transformation of trees in bud to trees in leaf, a fast-forwarding that characterizes one of our modes of experiencing time. But after commenting on time’s elasticity, Estes does something more astonishing. She catches the remote past projecting its likeness into a present reality. She catches the tilting of a plane that can cause the present to recede, usurped by history, and then history to recede, the present reasserting itself. All this in the space of a single line:

[…] The squirrel

lies in a bright red halo

of blood on the asphalt, its right arm

still running, even as the halos of martyred

saints Cosmas and Damian keep

rolling with their heads

in Fra Angelico’s painting.

Once the poem catches these two images—the freshly killed squirrel and the third-century martyrs—holding them on the plane of a single card, in one timeless hand, Estes suggests that “if they were in / Japan” they all could be mended by way of kintsugi. That is, the writer turns the rodent and the cephalophores into momentary contemporaries, momentarily immortal. First she frees them from their respective spots on opposite ends of a long timeline with that sly “even as.” Then she suspends them in “the Eternal City” via the subjunctive that borrows the squirrel and the saints (“if they were”) and spirits them collectively away. And this is where the wonder comes in: the poet puts this hologram directly in the reader’s hand. She doesn’t marvel for us. She marvels with us at the wild mirrorings that insist across time, not put off by differences of scale, circumstance, or significance.

And Last Day on Earth gives us the chance to marvel from the outset. Its writer hoodwinks chronos already in her first poem, “The Swallows Come Out.” Here, the speaker situates herself as both subject to and unbound by time.

[…] So I waited

at the airport, a woman beneath

a sign that said Gate B hold—what

Heloise and Abelard must have

been feeling when

they named their son Astrolabe,

an instrument for

determining one’s position

in the universe. The room where

they met in secret was not

far from Pont Neuf, the “new bridge,”

which is the oldest bridge

in Paris.

Nothing less than astonishingly, this poem, too, yokes the distant past and the present, implying a parallel that makes light of centuries and gender, recasting Heloise and Abelard as the speaker and her lover. That is, as with the squirrel and the martyred brothers, Estes creates a hologram here. Tilted one way, the poem holds up the image of its speaker’s current romantic relationship; tilted the other, an image of two storied medieval lovers comes to fore.

A later poem defies the same orthodoxies by way of hologram. Tilt “For the Time Being,” one way and what manifests is “Memories: slideshows of photos accompanied / by music [the speaker’s] phone itself had thought / appropriate to play along;” tilt it the other, and displacing the iPhone’s slideshow, what floats into view is an archeological find, in Oxyrhynchus, as incongruous as the contents of the speaker’s camera roll: “previously unknown lesbian erotica / by Sappho and fragments of the sayings / of Jesus, lying together.” Once again, then, Estes makes room for her readers to reel at the strange likenesses that prove time both consequential and not.

That said, in “The Swallows Come Out,” the poet (and we with her) feel more than the wonderful strangeness of the hologram’s flicker. We also have cause to wonder at time’s slow paradoxes, how, both invisibly and cumulatively, we find ourselves out of step with our own chronological markers. Estes, for instance, points out that the “‘new bridge’” becomes “the oldest bridge / in Paris”—and the validity of both titles sticks. Likewise, yes, the astrolabe gives way to GPS, but in the poem the instruments of the medieval astronomers and the modern-day air traffic controllers sit in close proximity, testifying to the abiding if evolving difficulty of “determining one’s position / in the universe.”

All of which is to say that this poem embodies the paradox of time—its quick-change holograms and its gradual accumulations—even as it also takes up the paradox of absence as presence (and vice versa). Most immediately, Estes dramatizes this contradiction of present absence (or absent presence) in transcribing the sign “Gate B hold.” Read that construction aloud, or read it speedily, and you hear or see the word “Behold” rather than the status of the traveller’s gate. The space between “B” and “hold” isn’t quite empty.

The phenomenon of substantial emptiness, as well, recurs throughout Last Day on Earth. And as with the paradoxes of time, this contradiction that binds absence to presence is one that Estes sometimes announces, repeatedly gesturing to music by way of analogy. In “Devekut,” she writes,

[…] Sometimes when playing a measure

of Beethoven, there is no note but

a chasm, which somehow still must be

played.

“A chasm, which somehow still must be / played,” precisely. And if Beethoven gives the poet a way to name the present absence, Monk helps her account for the absent presence.

Thelonius Monk: “Don’t

play everything

(or everytime) … Some music

just imagined …” the way

that bumblebees at

evening curl into

purple blossoms of thistle

and imagine the heat

that will stir them[.]

Estes takes this advice, along with Beethoven’s “chasm, which somehow must still be / played,” very much to heart. She does play the chasms: the “e” in “Behold,” for instance. But she also practices Monk’s restraint, like Michelangelo, who “carved / facieba” on his Pietá rather than the expected faciebat, “omitting the final letter t / and thus creating an imperfect form / of the imperfect.” She muses on the “vowels” in an old woman’s yard for some time before telling us that “voles are capable of empathy” and, elsewhere, on Christ’s miracle of “the many loves / of bread,” wrily noting “in hindsight, / I see they must have been / loaves.” That’s Estes embodying the paradox, refusing to play “everything / (or everytime).”

But refusing to “play everything / (or everytime)” also manifests, in this brilliant collection, as several erasure poems, such that, for instance, its opening poem “The Swallows Come Out” is followed, in the book’s second half, with the much sparser music of “The Swallows.” At least once, Estes works the same trick in reverse. Last Day on Earth includes two poems with the title “Pas Encore,” and the second embellishes the first: an improvisation, a riff on the same song, but with more played notes.

I could go on, charting more of Estes’s intertextual and intratextual echoes and erasures. I could point to other places where she explains the aesthetics of paradox, other places where she enacts paradoxes, be they loopholes in chronological time or teeming emptinesses or voiced silences. But that would only deliver you a third-hand amazement, a wonder filtered first through Estes’s witness and then mine. You would be far better off closer to the wonders themselves, the paradoxes that Estes will point out to you, like strange stars in the night sky, and the paradoxes Last Day on Earth in the Eternal City will enact right before your eyes.