LOST OBJECTS

At the beginning of Book Two of Lucretius’ The Nature Of Things—Book One, you’ll remember, sets up that the universe is built from atoms and the idea of the clinamen—Lucretius writes what to me is one of the more difficult of his arguments to adjust to a present ethics of encounter. Here’s A.E. Stallings’ translation of the lines for Penguin—note that they’re in rhyming fourteeners:

How sweet it is to watch from the dry land when the storm-winds roil

A mighty ocean’s waters, and see another’s bitter toil—

Not because you relish someone else’s misery—

Rather it’s sweet to know from what misfortunes you are free.

If you know Stallings, you know she loves rhyme. The lines above are when she’s at her best—formally clear, loping meter fitted to correct, though not necessarily meticulous, rhyme. If this already grates, I don’t know that I’ll be able to change your mind. I’ll say this. Stallings isn’t interested in spark and dazzle. Like the oddly shaped cookies hand-made every year by your grandmother or the riffs of Led Zeppelin, rhyme’s joy for Stallings is a conservative one. The familiar dull of butter and nuts, the inhuman tonic ring of proper rock and roll. Mark Van Doren instead of Anthony Madrid.

But back to the Lucretius. I’m guessing the above calls forth similar moments for those used to reading from older books. The clenching squeakiness of the repetition of “sweet” in lines about shipwreck and misery and other people leads to an insistent exoneration based on hand wavy historical context, Maimonides-level exegesis, or a meditative acceptance of the balance of good and evil. And then the sinking realization that you don’t not agree but that you can’t quite imagine positioning yourself in this way. And besides, Lucretius says, “Not because you relish someone else’s misery.”

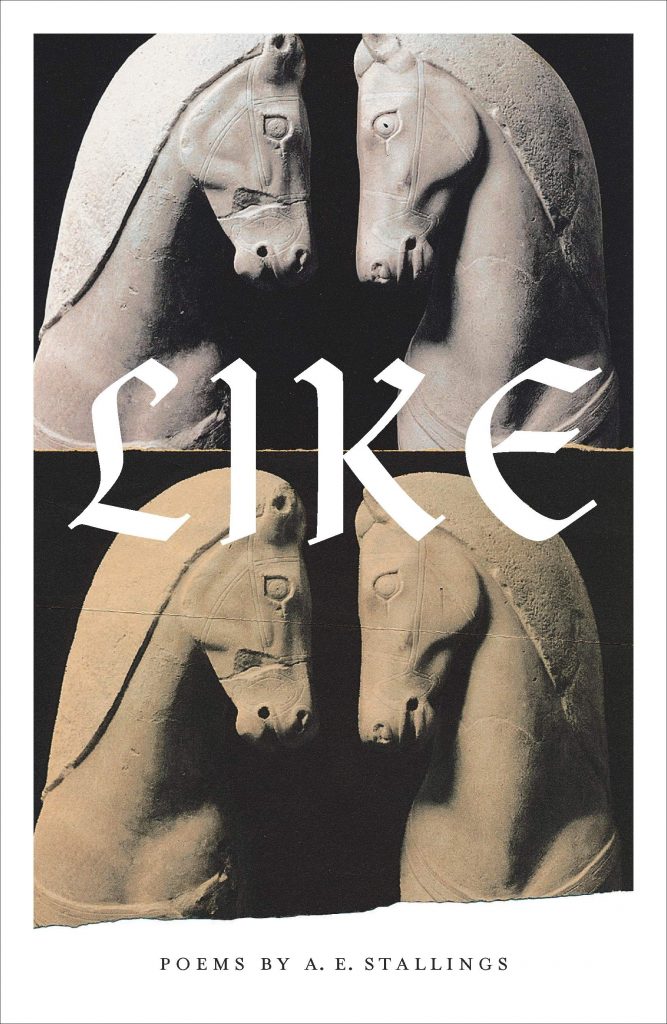

Rather than cherry-pick or dismiss one of her masters, Stallings uses him at his most fervid to read her own selfishness. It’s a gambit, especially for someone who’s already using so much Western Civ (Ancient Greek and Latin) in her work. In a poem called “Empathy” in Like, her fourth book of poetry and first for FSG, Stallings rereads and adapts Lucretius, thinking about the Syrian refugees risking their lives to come by raft to Athens, her adopted home. Here’s the first stanza and the last—the middle describes the voyage of the displaced:

My love, I’m grateful tonight

Our listing bed isn’t a raft

Precariously adrift

As we dodge the coast guard light,

…

Empathy isn’t generous,

It’s selfish. It’s not being nice

To say I would pay any price

Not to be those who’d die to be us.

I’ll admit the same level of reticence when reading this poem for the first time. It’s not just the sentiment—virtue signaling wedded to self-satisfaction—but the repetition of not to help the scansion and the rhyme scheme. Here, Stallings’ formal inclinations are at their worst. “Not to be those” is awkwardly joined and makes too clear the rhetoric of her rhyme. Even if she’s calling herself selfish, it feels unpleasant and distinctly unmodish to wed the resonant tying up of rhyme to a humanitarian crisis. But it’s a spectacular failure, no less so than a contemporary art piece that tracks the vectors of emigration and charts them onto canvas, or a hot take on the difficulties of writing refugee literature from the land of the free. If Lucretius can’t get it right, neither can we.

So, some of what she does well, some of what she does not so well. What does she do? Over four books of her own poetry and the translation of Lucretius, Stallings gives us three types of poems: shorter lyrics, classical translations (usually just excerpts, the Lucretius is an exception), and, my favorite, longer quasi-narrative poetry that muddles the two. There aren’t enough of the latter. She’s won the prizes and published with the presses—Guggenheim & MacArthur, Northwestern & Penguin. Now Like for FSG. Throughout, Stallings’ main line are the shorter lyrics. The poems are usually formal and usually rhymed—enough so that even when they aren’t, you’re convinced they are.

You can trace her biography through the shorter poems. Half of them are clearly about Stallings, first memories of home, then mostly poems about love and relationships. Later, her children. The rest are occasional or about a special object and often end with a quiet joke, as if written to begin a meal with light laughter. Here’s one of those poems in its entirety, “Jigsaw Puzzle,” from her third book, Olives:

First, the four corners,

Then the flat edges.

Assemble the lost orders,

Walk the dizzy edges,

Hoard one color—try

To make it all connected—

The water and the deep sky

And the sky reflected.

Absences align

And lock shape into place,

And random forms combine

To make a tree, a face.

Slowly you restore

The fractured world and start

To re-create an afternoon before

It fell apart:

Here is summer, here is blue,

Here two lovers kissing,

And here the nothingness shows through

Where one piece is missing.

Her main stylistic gestures: snappy rhymes, singable meter, some unfortunate enjambment in service of the rhyme and meter, but mostly easygoing spoken English. One assumes the puzzle is also her poems, delineative and interlocked by form.

Stallings’ first book, Archaic Smile, circles around home, lost pets, and other animals, but she also projects her persona into the women of classical myth: Daphne, Arachne, Medea, Ariadne, etc. “Medea, Homesick” begins, “How many gifted witches, young and fair, / Have flunked, been ordinary, left the back- / Stooping study of their art, black / Or white, for love, that sudden foreigner?” You can probably see where the poem goes. Archaic Smile is filled with sentiments like this—good poems, but mannered, over worked, and in stone.

Her second book, Hapax, is better. There, Stallings isn’t Medea, but Cassandra: “Our speech ever was at odds / With the utterance of the gods: / Tenses have no paradigm / For those translated out of time.” The poet begins to lose herself in her myths. The characters no longer only help her explain her past, but speak to her future.

After the first section, where Stallings burns off the last of the poems about her childhood—the book gives us three more easygoing sections of travel and young love, but then book ends with a poem about called “Ultrasound.” Here’s the first two stanzas:

What butterfly—

Brain, soul, or both—

Unfurls here, pallid

As a moth?

(Listen, here’s

Another ticker,

Counting under

Mind, and quicker.)

Like Apollo blurring Cassandra’s speech, the baby inside of Stallings takes her outside of her own time. The poem, too: I love how Stallings uses tempo in these two stanzas. First how the slow pace and eye rhyme match the higher, adult notions in the first stanza, and then how the accelerating “ers” in the second are put in service of an infant’s heartbeat. This oscillation is common in the shorter poems—more fanciful notions or questions are resolved through sturdy, yet playful observations that are usually wrapped up in formal exploration. This effect at times makes the poems noxiously stable, as if any inquiry just needs a bit of decoration and a bow. But Stallings’ best work—the longer poems—take this stability and curls it around itself. Myth’s night comes into contact with Stallings’ representational daylight.

Much is made in the promotional copy (and other reviews) of Stallings’ decision to arrange the poems in Like alphabetically. Lost and Found, 18 pages and the longest poem in the book by far, still comes as it should, smack in the middle. It’s a series of thirty-six ottava rima stanzas that begins:

I crawled all morning on my hands and knees

Searching for what was lost—beneath a chair,

Behind the out-of-tune piano. Please,

I prayed to Entropy, let it be there—

Some vital Lego brick or puzzle piece

(A child bereft is hiccoughing despair),

A ball, a doll’s leg popped out of its socket,

Or treasures fallen through a holey pocket.

By the eighth stanza it’s night, Stallings is asleep, and she’s searching in her dreams, “in a dusty place / Beneath a black sky thrilled with stars, ground strewn / With stones whose blotting shade seemed to erase / The land’s gleam.” She is on the moon and “A black sky thrilled with stars” is one of the best phrases in the book.

Why the moon? It’s where lost objects go; Stallings “mark[s] / The mounds of keys or orphaned socks, dropped pills / (Those were the things that I could recognize).” Mnemosyne is there, though it takes Stallings most of the poem to remember who she is. The moon holds other objects. “Look there” Mnemosyne says,

Those are the halls to which we can’t return—

The rooms where we once sat on others’ knees,

Grandparents’ houses, loving, spare, and stern,

Tree houses where we whispered to the trees

Gauche secrets, virgin secrets where we’d burn,

Love’s first apartments.

What else? Not only things longed for, but objects never held: moments of lapsed attention and “letters / We meant to write and didn’t—all the unsaid / Begrudged congratulations to our betters, / Condolences we owed to the lately dead, / love notes unsent…”

Stallings’ merit are these decisive figures. They are the puzzle pieces of the poem above, pieces of absence that “align / and lock shape into place.” But as the poem gets longer, and her attempts at notating absence extend, she allows herself moments of surprising imagination:

Skittering round us, skirls of silver sand

Would swarm and arch into a ridge or dune,

And then disperse, as if an unseen hand

Swept them away (there was no wind), then soon

Accumulate elsewhere, a sarabande

Of form and entropy, a restive swoon

Of particles, forever in a welter,

Like starling murmurations seeking shelter.

There was no wind. A sarabande of form and entropy. I could happily re-type the rest of the stanza in italics. This combination of philosophical terms with concrete imagery is Lucretius again. These are the sands of time, Mnemosyne explains. By the end of the poem, Stallings has returned to her daily life with more focus, even on the domestic: “There are lunches to make, I thought, and tried to find / Some paperwork from last week I’d mislaid.” If there was no wind on the moon, there is wind here: “I saw the aorist moment as it went.” Stallings has unified Mnemosyne and her poems, “To live in the sublunary, the swift, / Deep present, through which falling bodies sift.” How sweet to read them.

–Devin King

Like

A.E. Stallings

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

$24 hardcover

September 2018