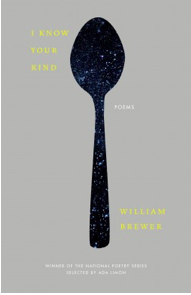

I Know Your Kind by William Brewer

Milkweed Editions

$16, 95 pages

published September 2017

According to a recent New York Times article, drug overdoses are now the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 50. Perhaps no region has been as decimated as Appalachia, where a handful of states account for one-fifth of all overdose deaths in the U.S. William Brewer’s first book, selected by Ada Limón for the National Poetry Series, casts its aching, hallucinatory poems against this backdrop of addiction and hopelessness in the poet’s native West Virginia—particularly the town of Oceana, which has earned the sinister nickname Oxyana. I Know Your Kind endures as a riveting and poignant debut where Brewer captures the horrors of substance abuse, the spiritual rigors of recovery, and ultimately, the fraught relationship between an obliterated landscape and self-obliteration.

Brewer renders addiction with exacting savagery, never sparing readers from the monotonous and escalating damage it inflicts upon the mind and body. In “To the Addict Who Mugged Me,” we encounter a dope-sick speaker who has been robbed of his last hit, who asks himself and us, “What’s more brutal:/A never-ending dial tone/chewing the receptors in your brain,/or waking up in an alley with a busted face,/teeth red and penny-sweet, the rain/coming down clear as gin?” It’s a rueful rhetorical question, since the speaker endures both of those sufferings—withdrawal and assault—which makes the poem’s last turn more striking. Seeing his own desperation reflected in the mugger’s crime, the speaker ends liturgically, hoping that “this throbbing in my brain/is now the sound of your rowing toward/what I pray is, if not home, then mercy.” A terse, alliterative lyric, “Leaving the Pain Clinic” wrestles with the shame and impatience of lying one’s way through medical bureaucracy to garner a bogus pill prescription. What makes the poem all the more haunting is the realization that the speaker is only one among many in the waiting room pursuing this same ruse, and when the pills kick in, it’s like the “soft rain of sparks that pity sometimes is,/how it mends the past like a welder seams metal.” A related poem, “Early Oxyana: An Anecdote,” sparsely recounts how the speaker and his friend Tom flipped a coin to see who would get their hand bashed with a hammer in order to justify a trip to the emergency room. One of the most disturbing truths acknowledged in I Know Your Kind is that an opioid high is genuinely ecstatic, a fact that Brewer, to his credit, presents not as a rationalization, or as a justification, but as an explanation. “In the New World,” the collection’s lone prose poem, OxyContin is “a moon’s tooth,” a needle is “god’s antenna,” and heroin is “heavenquick,” and each morning addicts “wake up astonished / in a heap of golden dust / with nothing left.”

Despite the book’s focus on the daily depravities of addiction, I Know Your Kind dedicates just as much space, if not more, to detailing the rocky road to recovery, which Brewer depicts in potent spiritual terms. Indeed, as the book unfurls, even his titles turn scriptural: “Overdose Psalm,” “The Good News,” “The Messenger of Oxyana.” Lyrical and imagistic, “Clean Days in Oxyana” offers a striking meditation on “the five buck/heads over Crockett’s bar,” as the speaker ponders if “one of them must have wanted it, if only/a little, the end—an orange star blooming/between the elms.” By comparing a fatal hunting wound to addiction’s bleakness, Brewer spotlights early sobriety’s seemingly-impossible demands and the allure of death for those who feel they have transgressed beyond redemption. “Halfway House Diary” catalogs the tedious progression of time, where “every hour is a version of an hour/coming toward us.” Seeking his own rebirth, the speaker recalls “thick ropes of mosquitoes/swarming” down the nose of a dead cow and how its decaying flesh sank “drowning in the sound of rain.” Brewer rejects the apparent finality of the scene, however, preferring instead to regard it as “the meadow becoming two kingdoms at once,” just as the addict’s former self must die in order to permit health and hope to bloom. This resurrection theme blazes in the last dozen lines of “Detox Psalm,” where Brewer’s writing is taut, sonorous, and surreal:

I thought to give myself

to the dogs, but they only gnawed

my thighs. With the waves’ jade

coaxing, I heaved my every organ

through my mouth, then cut a mouth,

at last, in my abdomen and prayed

for there to be something more divine

than the body, and still something

more divine than that, for a torrent

of white flies to fly out of me,

anything, make me in the image

of the bullet, I begged, release me

from myself and I will end a life.

In these poems, West Virginia itself—impoverished, depleted, hardened— antagonizes its residents, and the landscape’s stark juxtapositions of beauty and barrenness, pride and poverty compel many to seek the fleeting escapism of drugs. Everywhere the reader turns there are wrecked mountains, ghostly machinery, and rusted vehicles. The book’s sprawling, cinematic opener, “Oxyana, West Virginia,” scans the ruinous terrain, including “Hog Hill where Massey Energy/dumped cinder, the gray waste/between breaths, poisoned trees/black like charred bones,/where we burned cars while girls/wrote our death dates on our palms/with their tongues.” “Daedalus in Oxyana” ventriloquizes the mythical father, who can no longer stand “the mountain’s hull/chewing out the corridors of coal” and ultimately surrenders to “scraping out my veins,/a trembling maze, a skein of blue.” “Appalachia, Your Genesis” is one of the book’s most surreal inclusions and contains a premature epitaph for the entire region: “Had you a head/you’d have a mouth/and moan the song of a cello played by flame.” One of the final poems in the book, “Today I Took You to Our Oxyana High School Reunion,” narrates a truly wrenching vignette, where two-thirds of a graduating class are dead, and “when a classmate walked up/and pointed at you/in the urn I cradled like an infant/said that motherfucker/stole forty bucks from me.”

Brewer’s writing isn’t flawless, however. “We Burn the Bull” sprints through an opaque account of friends torching an animal’s corpse, veering toward melodrama when the bull’s tongue becomes “some surrender flag” and the burners themselves seem “like earliest man bewitched by heat’s coil.” Even at seven pages, “Resolution” fails to establish a unified tone, and is full of flimsy lines (“I know this isn’t/a solution,” “I don’t need answers”) that make it read more like a gushy draft than a polished piece. Reminiscent of Marianne Moore with its unusual syntax and staccato rhythms, the self-conscious funkiness of “Ode to Suboxone” leads to some awkward phrasing (“I punctuate the minutes with much coffee”) and questionable metaphors (“my double-wide of debt,” “turning inside out/a precious jewel”).

Despite these concerns, I Know Your Kind may be one of this year’s most important books of verse since its brutal music confronts the taboos of addiction while simultaneously offering hope for overcoming them. While our purgatorial political discourse fails to produce the imagination or courage necessary to combat the opioid epidemic, it is heartening to know such things can be found among our poetry.

Adam Tavel won the Permafrost Book Prize for Plash & Levitation (University of Alaska Press, 2015). He is also the author of The Fawn Abyss (Salmon Poetry, forthcoming) and the chapbook Red Flag Up (Kattywompus, 2013). Tavel won the 2010 Robert Frost Award and his recent poems appear or will soon appear in Beloit Poetry Journal, The Gettysburg Review, Sycamore Review, Passages North, The Journal, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and American Literary Review, among others. He can be found online at http://adamtavel.com/.