When The Poet is a Master of Multiple Arts:

Michelle Whittaker and Aaron Caycedo-Kimura

Interviews and Poems

by Frances Richey

William Blake, Ellen Bryant Voigt, Dylan, Bishop, Joni Mitchell, PJ Harvey,

Leonard Cohen, John Lennon, Tom Waits, the list of multi-talented artists is

endless. How does each discipline influence the others in an artist’s body of work?

In the following interviews, Michelle Whittaker and Aaron Caycedo-Kimura, both

poets with multiple talents, offer a window into how mastering more than one

discipline creates synergy and flow as they move from one art to another in their

creative lives.

An Interview With Michelle Whittaker

FR: Which came first: making music or writing poetry?

MW: Music came first for me with the violin, then the piano. My mother loved classical / ballet music since there were two main stations in Jamaica [West Indies] where she grew up. Since my dad often played reggae music in the basement of the house and on the highest volume, whose bass shook the walls, my siblings and I used to make up our reggae songs or lyrics. I started writing songs in high school when I learned to play piano better. My library card was one of my best friends, as I listened to different types of classical [and other genres] and piano works. Thankfully I was exposed to diverse composers through playing in the school orchestra. I became more intrigued by poems from high school English teachers. I became very inspired by Tori Amos, grunge, and neo-soul, to name a few, in my late teens and twenties. I liked the idea of the singer-songwriter, but I went to study and write [classical] music composition in college and then creative writing.

FR: What got you started playing piano? Who are your influences? Did you have one teacher who stood out?

MW: I started playing piano when my dad brought home a piano. I don’t remember if it was an electric or an upright. I think he rented it and could switch from time to time. Since I was already playing the violin at school, I slowly realized I could transfer the same music notes to the piano. Eventually, my parents said I was taking piano lessons. I played violin for about ten years. I regret not continuing orchestra in college. I loved Chopin, Mozart, Beethoven, and especially J.S Bach. Russian and French composers. But I listen to all sorts of music.

A favorite teacher who stood out? My first orchestra teacher, Mr. Biava. He spoke with a thick, wonderful accent, all smiles, and spoke in aphorisms. He constantly introduced us to new music and encouraged me in a stern but caring way to participate in NYSSMA and practice daily. As a conductor of color, his encouragement made it feel safe to be myself.

FR: How did you get started writing poetry? Who are your influences?

Did you have a teacher who made all the difference?

MW: I don’t mean to sound like I am judging, but I had excellent English teachers in high school. They seemed interested in analyzing life. I had an especially wonderful poet/teacher named George Dorsty, a haiku master and storyteller. He introduced me to many classical and modern poets and my first literary magazine. Mrs. Packard, the first black poet I met, shared a book with me about poems inspired by art and nature that I still have decades later. I was a closet poet for a while. But in graduate school, Julie Sheehan and Star Black were great teachers and supportive of the development of my writing and craft. I find the most inspiration from the late 20th century and early 21st century poets. I had a crush on Anne Sexton’s and Rita Dove’s work. The language was surprising – and it seemed honest, despite disturbing subjects at times. The Long Island community of poets was very nurturing, as well as some poets I met during my Cave Canem retreat and whose work I still follow.

FR: Can you put into words how your music influences your poetry and vice-versa?

MW: I noticed many craft techniques and devices in writing poetry apply to writing music – meaning there are many options to consider despite trends. In college, I often had to set poetry or text into chamber music and then had other musicians interpret it, which was always a little nerve-wracking. It was a helpful exercise. I usually recite my poems into a recording device multiple times as part of my writing process.

FR: Do you listen to music while you write? If so, what do you listen to?

Do you write in cafes with the white noise, or do you need silence?

MW: Yes. I mostly listen to music that doesn’t have lyrics when writing prose, but when I write poetry the music I listen to can have lyrics. Mostly it’s about the mood. Years ago, I worked three jobs for a long time, so I wrote poems highway driving or at my office job after hours. Regarding Surge, I wrote in my car, or at 5 am before I had to teach morning classes. For my newest manuscript, I wrote in Astoria, Queens, at a cafe called Queen’s Room almost every evening and sometimes on the train commute. Since moving to Long Island again, I haven’t found a place to replace that consistency. But the Long Island Sound does have a sonic quality. Therefore, near the beach has become a new place.

FR: I love how “surge,” in all its definitions, runs through your book, Surge, figuratively and literally. Would you say something about what inspired you to write this collection

MW: Thank you so much for that observation. I think the collection spoke to a coming-of-age process as I became disillusioned by the “randomness” of violence in the world and my own life or past. Surge seems to represent that natural sense of anxiety inside us all, the fight or flight or freeze mechanism, and I suppose many of the poems in the book are about coming to terms with that part of humanity. It is also dedicated to people no longer with us or me.

FR: Sometimes you bring music and musicians explicitly into a poem as in “Identification.” In other poems you are less explicit, but the music is there. Would you say something about that?

MW: Perhaps it was semiconscious. In most western music, we deal with whole and semitones, but there are quarter tones and even other tones in between those we might not realize. So music was always a present companion and what I did for a living. In hindsight, besides teaching and writing music, I had a piano-duet partner, a musician from Hungary, for years, I helped to produce opera events, volunteered to help music events in the community, edited albums, and even dated musicians and found best friends. My basic survival revolved around music, so I think it was inevitable that extensions such as my poetry would sort of “harmonize” or intersect with that, whether consciously or not. Some are personal associations like in “Identification,” as I was probably struggling with a Schubert piano composition. Some other associations are about others. An example of this poem is “In the Afterlight,” formerly called “The Fortune Cookie,” dedicated to Jordan Davis, my cousin’s relative who was murdered at a gas station for playing music too loud. I might have developed a subconscious pattern with music as an act of rebellion to the point that even the call for silence in Surge is not at rest. Prayers and meditations still pulse as music. This concept has continued as a more deliberate act in my new manuscript.

FR: If you were going to back up Surge with music while reading poems from the book, either in silence or out-loud to yourself, or out-loud to an audience, what music would you choose for each or all situations?

MW: Since the book is in three sections I can name four or five songs or compositions for

each section:

In the Afterlife

Agustín Barrios, Francisco Tárrega classical guitar composers

Frida’s Film Soundtrack

Yann Tiersen’s Amelie [French film] soundtrack

Burning Spear

Black Uhuru’s Red

Surge of Light:

“A Wolf at the door” and “Exit Music” (for a film) by Radiohead was on repeat. Really,

anything Radiohead.

Tori Amos’ brilliantly orchestrated Boys for Pele and Little Earthquakes

Leontyne Price’s “La Forza del destino” by Verdi was on repeat.

Shostakovich Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110: Allegro Molto

In the Afterlife of Children

Whole albums of Nina Simone

Claudio Monteverdi – L Magnificat: Et misericordia

Mariah Carey’s “Vanishing”

George Michael’s “They Won’t Go When I go” – Really the whole album is a vibe.

Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G maj. esp any recording by Martha Argerich

Poems by Michelle Whittaker

In the Afterlight

for Jordan Davis & Liam

What is the speed of dark?

Is that like what is the speed of black?

or the speed of a stallion beauty turning corners?

What about wild horses barreling down a Moroccan beach?

What about a boy not foreign to me who sleeps in their path?

What is the speed of dilation?

Is that like not really recalling?

the speed of shuttering eyes?

What is the speed of the involuntary? the hard-wiring? and on the fritz?

What is the speed of forcible suspension? or the permanency of no return?

What is the speed of saying no? and meaning no more?

Is it like the speed of being chased down?

or the speed of light? or the speed of gun fire?

or the lightness of a streaming bullet?

Is it like the speed of ripping through cells?

I wish understood physics,

for it sounds like the speed of a bull

ramming into a windowless matter.

almost like the speed of a power outage?

or powerless and under age?

for what Is the speed of dark?

or the closing and then opening wound?

Is it like bagging a body?

I wonder,

what is the speed of the emergent spirit?

Does it sing like a lark

or spike like a nightingale?

from Surge

The Labor of Carrying a Diagnosis

after J.S.Bach

The last movement

of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Concerto

for Two Violins, Strings and Continuo

works for memorizing the center of D minor.

It is good for identifying the sound

before the noun like she inside the shears.

It is good for throat clearing another’s larynx

almost like the wrangling of course tresses.

It works for stippling gestures or shaving

the bottoms of hairs curling in

before Getting Ready.

Bravery. I feel

God. O I feel good for pushing

out small fires, fanning that fan’s fan

from alerts forming any higher inside the body,

in from the sleights as if Saturn devoured

ventricles into vengeance – but Bach works

for understanding this as counterpoint, counterclaims,

and for those contrarians – it’s good

for the sacred secular and for second opinions.

This is good for Getting Ready.

Bravery

or interning each other’s specked eye,

for locking gazes across a dressing gown

for unclasping the speculum, for entering

each other’s stairways and adjustments of spines.

Ways to subvert.

Ways of the breath.

Ways of the mouth.

Slipping under the lingering

weighs beyond the coursing

Getting Ready.

Bravery.

Hot and flashing, hands to neck

clavicle to shoulders, right to mid,

intravenous to tense, left to lowered,

rift to driftwood, drift to pain

O Conversion O Convulsing

thighs fanning as the fan

spins out – and Bach’s not even pentatonic.

This mode is good for interlocking,

like an Operatic trill

holding its metallic turn,

downside & for the Opening.

Oh, that Opening –

Hum, Burn, Sun.

O layers of the Land and Sea.

Help Me.

A Field Guide for a Positive Mental Attitude

Believe that you will spell Rhododendron Road correctly

by the third try.

When you drive past your childhood home,

don’t overanalyze improvements as a setback.

Although the ignition coils in your car are decades old,

accelerate up the dirt path with swerve and intention.

A field of Delphiniums is worth the wear and tear.

When recalling how your lover relaxed into a coffin as if it were a hammock,

reread his last letters from Kathmandu.

Repeat, I can bear it.

Learn to respect that silence rarely means rest.

When you see how the lone Egret returns to the capillary waves

replay the opening scene of your screenplay you will never write.

At every red light, wipe away the smear of your mascara in the rearview mirror.

When you cannot loosen the lug nuts, recite that Wallace Stevens poem

about they who rise from the misty Cliffs of Moher –

or try AAA again.

If you must fold your anxiety into sleep,

then it’s okay to take a back seat.

When your dead lover taps the middle of your forehead,

remember the image of two Buddhist Monks and two Barnacle Geese

diverging on a dissected path.

Stare through slots at what’s no longer coupling with dusk.

When mosquitoes enter as misquotes at stage right, it’s time to walk for help.

Repeat, I will grin and bear this.

Follow the panicles of Creeping Phlox, and the yellow shine under the power lines.

Give gratitude to the distillation of a hinterland that won’t let go of rain.

But when it does, and the water gathers on the road, and the disarray of debris rakes at ankles,

blame infrastructure, and not nature.

Repeat, I can bear this.

I can bear this even when you can only think of how you cannot birth children.

Repeat, I cannot bear children until you can no longer discern vanity.

Like a single-cell thunderstorm, reproductive death

is rarely graceful despite its grace.

Over earbuds, listen to anything Rachmaninoff for stressing the deep end

of strings, trumpeters, timpanists, and glorifiers.

Listen to anything Tori Amos for stressed endings with once loved strangers.

Memorize the tonal distinctions between the untimely rumblings

of hunger & instinct & kelp.

Patience holds reasonable promise in the clench of its jawline.

Let your throat pain repeat, this body is full of silent alarms.

An Interview With Aaron Caycedo-Kimura

FR: Which came first: painting or writing poetry?

AC-K: Painting came before poetry by about six years, but before painting and poetry, I was a musician. I majored in music performance and earned a BM and MM in symphonic percussion. However, during my last year of grad school, I came to the conclusion that I wouldn’t be happy with a career in music. After some post-grad soul searching, I realized that I had always been more visually oriented. So, I eventually picked up computer graphics to pay the bills and began exploring art. Looking back, I think it makes perfect sense that I became a poet. Poetry brings together my various artistic pursuits—music and visual art, sound and images.

FR: What got you started painting? How old were you?

AC-K: Growing up, I was always drawing or making something, but music was the art my parents encouraged me to pursue, both privately and in school. It wasn’t until after finishing grad school, my music education, that I started exploring visual art as a possible life direction, and it wasn’t until 2004, at the age of 41, that I started to seriously pursue painting. Right before that, I was working in the corporate world for an investment management firm—computer graphics for the marketing department. I wasn’t cut out for the corporate world, so I decided to leave and pursue the dream of becoming an artist.

FR: Was Mrs. Mullane (from a poem in Common Grace) your first inspiration? Who are your influences now? Were there other teachers who made all the difference?

AC-K: Mrs. Mullane was my only art teacher growing up. Between sixth and seventh grades, I enrolled in a local summer program and signed up for her ceramics class. It was the only class I really wanted. The other ones were music-related, which my parents wanted me to take. Mrs. Mullane was one of the kindest and most encouraging people I had ever met. Even though I knew her for only a couple of months, she left quite an impression on me. I still have in my studio the ceramic bowl I made in her class. She planted a seed, an encouragement, that I could indeed make art if I wanted to. I’m mostly a self-taught visual artist. I took some classes years ago after leaving my graphics job in corporate America, but what I do today is largely a result of working on my own.

FR: When did you start writing poetry? Did you show your writing to others or did you keep it private for a while? Did you have a particular teacher who encouraged and/or mentored you?

AC-K: I stared writing poetry in 2010 at the age of 47. When I was growing up, poetry wasn’t taught very well in school, so I was never really that interested. In 2009, Luisa, my wife, also a poet, left the law profession to become a writer. She took a poetry class at Southern Connecticut State University and began showing me drafts of her work for feedback. I had no clue what to say. I thought that if I were to study on my own and start writing, I would eventually be able to give her some reasonable feedback. She also started taking me to poetry readings. With all that inspiration, I couldn’t help but try my hand at it. I immediately began showing Luisa my first efforts. When she was accepted into Boston University’s MFA program in 2012, I became more serious about my writing. She would come home and tell me what she learned, and I would try to apply that to whatever I was working on. Seven years later I went through the same program. Studying with Robert Pinsky, Gail Mazur, and Karl Kirchwey was a dream come true. I’m also grateful for my cohort, which was made up of remarkably gifted people. A few of us still meet online from time to time to workshop. It was the best thing I have ever done for my creative life.

Before going to BU in 2019, I was writing and getting some poems published here and there, but I didn’t have a strong direction. Poetry still felt like something I just dabbled in. I had never taken a poetry class in school or been in a poetry workshop, so in 2017, at Luisa’s suggestion, I applied for AWP’s Writer to Writer Mentorship Program. I was accepted and paired with poet Matthew Thorburn. My writing life was forever changed. Matt taught me so much and brought me to a level where I felt like I could actually apply for an MFA program. Matt and I still meet every two to three weeks online to talk about all things poetry and workshop our latest poems.

FR: Can you put into words how your visual art influences your poetry and vice-versa? Are there any examples you can point to in Common Grace where your sensibility as a visual artist is there, apparent or subtle, in your choice of images, style and/or shape of the poem?

AC-K: I suppose I can say that since painting came before poetry, it influenced how I approach my writing. I think of the act of painting more like constructing or sculpting rather than “painting.” I build my work with individual strokes, and each swatch of color holds information that when viewed with all the others, creates the piece. A stroke (which has temperature, tone, intensity, and color) is equivalent to a word (which has sound, tone, and meaning). When I’m making a poem, I’m painting, but I’m just doing it with words. With respect to structure, sometimes I employ inline spacing, like I do in my poem “The Fern.” Commenting about this poem, poet Arden Levine once pointed out to me that she saw my brush strokes in the way I structured the poem. I had never really thought about it, to be honest, but I think she’s right.

FR: Would you say something about those beautiful one line poems interspersed through the book? So much meaning carried in a single stroke.

AC-K: I love the idea that one line, a handful of words, can be a complete poem. I try to construct my one-liners with image, sound, and meaning, just like I would a longer poem. The titles do a lot of work, too. Since I wanted my book to have variety and range, I thought the one-liners would offer the reader a nice surprise here and there. I think the first one-line poem that I ever heard, and which inspired me, was at a reading given by David Ferry. He recited his “Turning Eighty: A Birthday Poem”: “It is a breath-taking near-death experience.”

FR: Would you talk a little about your poem “In the Studio”?

AC-K: “In the Studio” is about the time I decided it was better for me to choose the joy of making over the mistake of pleasing others. It’s about doing your own thing no matter what’s going on around you, like the poet/painter (not to mention singer/songwriter) Joni Mitchell, whom I mention in the poem. Life is too short, as implied by the mention of my father’s death, to sacrifice the joy of being true to your artistic self. All the poems in Common Grace about my painting life can be read as ars poetica as well. If making art and poems doesn’t bring me joy, I don’t want to do it.

FR: Would you say something about what inspired you to write Common Grace?

AC-K: Common Grace was not a project book, but rather a selection of poems that I had written over a period of nine years. During this period I wrote a lot about the life Luisa and I have built together and about my parents. My father passed away in 2011 and my mother in 2015. Since the book was my first full-length collection, I also wanted to include a section that introduced me as a person and artist. When I read a poetry book, I’m really going in to find out what I can about the author. That’s what interests me the most.

FR: Does your poetry remind you of any particular music?

AC-K: If I had to say what kind of music my poetry reminds me of, I think of Ryuichi Sakamoto. Most people know him for his movie scores like The Last Emperor and Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence.

FR: How do you divide your time between painting and poetry?

AC-K I paint and write whenever I can. Even when there’s no inspiration, I try to stay engaged in some way. I just show up to the canvas and/or page. I try to keep them going at the same time. It’s nice to be able to go back and forth between the two, but there are seasons when I do one more than the other.

FR: Do you favor one more than the other?

AC-K: Right now, I’m enjoying them equally. Maybe poetry just a tad more. I like to say that I’m a poet because sometimes I like to paint without the material mess. I also like the flexibility. You can do it almost anywhere. It only requires a laptop or phone, or a scrap of paper and pen. I like the specificity of communication in writing as well.

FR: What’s the biggest similarity in the way you write and paint? What’s the biggest difference?

AC-K: I think the biggest similarity is the general way I shape a poem or painting from start to finish. I start a painting by blocking in the entire canvas, just to get a sense of the overall composition of tones and temperatures. Similarly, when I start a poem, I just write all that I can about an idea in a brain drain sort of way without paying much attention to grammar, punctuation, or structure. Each time I return to the canvas or page, I make more and more decisions about how to develop the piece, how to sculpt it.

I think the biggest difference for me is that a painting tends to be more planned than a poem. Since I paint representational work, I have a good idea of the piece’s composition before I start putting anything down on canvas. A poem is more fluid. It can take you to unexpected places. It can change form.

Poems by Aaron Caycedo-Kimura

Siren

Here, right here,

right here, right here,

a bird calls from somewhere

in the backyard woods.

Her song reminds me

of an ex. I’m afraid

if I get up from this chair,

follow, she’ll have me

at the top of the hickory

with no way to get down.

Triangling

I unclip my Alan Abel

from the music stand.

Chrome-plated brass,

fashioned like a knitting mill

spindle bent in three.

I lift it face-level

with my left, a #3

Stoessel in my right.

With conductor in view,

I breathe out, strike

the sweet spot of overtones

at the lower corner.

Four sparks—one arc,

force, and timbre.

I say all this

to be impressive. Some

think the difficulty

of playing this instrument

must be counting all

the measures of rest.

But I don’t need to.

I know the music.

I have to—the maestro

is swatting flies tonight.

The real problem is how

to look cool with this

pre-school noise-maker,

especially to the cellist

with the slight wave

in her long black hair.

Edamame

lumpy smile color

of spring bite

the bump just enough

to push the bean

onto your tongue hidden

in your mouth like saying

one thing thinking another

salted pod after salted

pod when the bowl

was empty I let her

keep the cardigan

my mother knit me

pale napkin

piled with husks

Pool

Across the street, a wild turkey circles

the parked blue Camry, single-pecks

at the polish once every few steps.

In his reflection, he sees another tom,

though tinted, silent, skewed.

Tassel like a tie. Or is he admiring

himself? After forty minutes, he turns away

to search for his rafter. As the sun dips

behind the mountain. As his image fades.

BIOS

Michelle Whittaker

Michelle Whittaker is the author of Surge (great weather for MEDIA), awarded a Finalist Medal for the 2018 Next Generation Indie Book Award. She has received a Pushcart Special Mention, Cave Canem Fellow & New York Foundation of Arts Fellowship in Poetry. Her poems have been published in the New York Times Magazine, New Yorker, Shenandoah, upstreet, and other publications. Currently, she is an Assistant Professor in the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stony Brook University and Guest Poetry Editor of The Southampton Review.

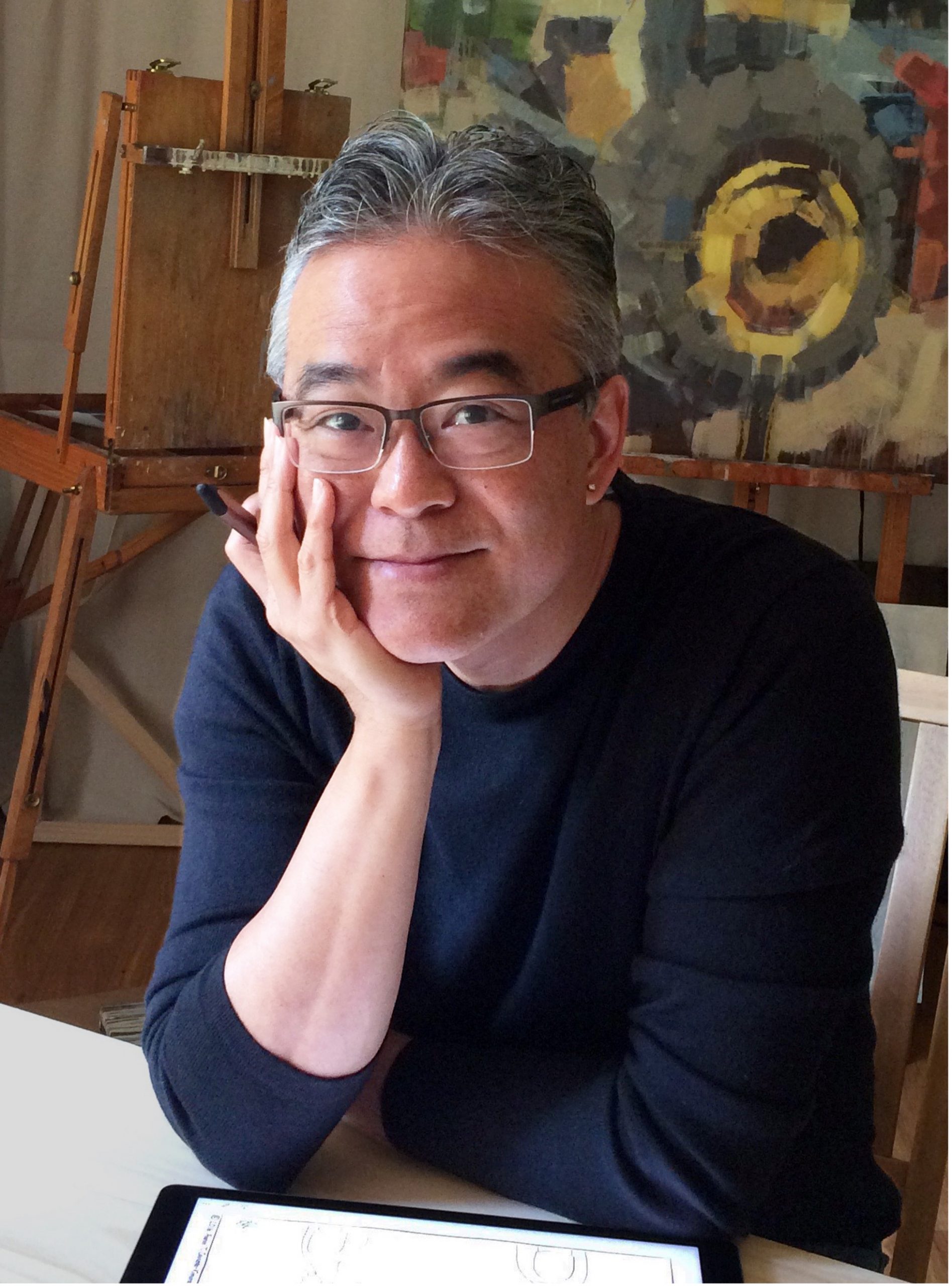

Aaron Caycedo-Kimura

Aaron Caycedo-Kimura is a writer and visual artist. He is the author of two poetry collections: Ubasute, which won the 2020 Slapering Hol Press Chapbook Competition, and the full-length collection Common Grace, forthcoming from Beacon Press in October 2022. His honors include a Robert Pinsky Global Fellowship in Poetry, a St. Botolph Club Foundation Emerging Artist Award in Literature, and nominations for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best New Poets anthologies. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Beloit Poetry Journal, Poetry Daily, RHINO, Pirene’s Fountain, Iamb, upstreet, Verse Daily, DMQ Review, Poet Lore, The Night Heron Barks, and elsewhere. He currently serves as a member of the Slapering Hol Press Advisory Committee and as a reader for Beloit Poetry Journal. Aaron earned his MFA in creative writing from Boston University and is also the author and illustrator of Text, Don’t Call: An Illustrated Guide to the Introverted Life (TarcherPerigee, 2017).