5 under 35 Plus

JN It is with deep honor I introduce the second installment of this feature. Below are twelve startling poems by six exceptional poets. I learned so much not only through their work, but through their insightful answers to the interview questions. In this feature you will find a fabulous array of poetic approaches by poets with very different life/artistic experiences informing their verse. The following poems boldly dance between the beautiful and the grotesque, the pristine and the broken, reminding us that even these kinds of distinctions often live in a fraught and liminal space and are subject to unexpected mutability. These are poems of transmutation that will change the way readers understand the world around them. It is my sincere hope that the poems here are ones you will return to often. I am so excited to follow the careers of these fine poets. I hope, after this feature, you are too.

JK Anowe, Igbo-born poet and teacher, is author of the poetry chapbooks The Ikemefuna Tributaries: a parable for paranoia (Praxis Magazine Online, 2016) and Sky Raining Fists (Madhouse Press, 2019). He’s a recipient of the inaugural Brittle Paper Award for Poetry in 2017, and a finalist for the 2019 Gerard Kraak Award. Recent works appear in Kissing Dynamite, Glass Poetry, The Gerard Kraak Anthology 2019, The Shore, The Muse (University of Nigeria’s literary journal), Agbowo, 20.35 Africa: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry, Fresh Air Poetry, and elsewhere. He’s Poetry Chapbooks Editor for Praxis Magazine Online. He lives, teaches, and writes from somewhere in Nigeria.

John A. Nieves has poems forthcoming or recently published in journals such as: North American Review, Poetry Northwest, Southern Review, 32 Poems, and Copper Nickel. He won the Indiana Review Poetry Contest and his first book, Curio, won the Elixir Press Annual Poetry Award Judge’s Prize. Hi work has recently been anthologized in Verse Daily and The Eloquent Poem (Persea Books). He is associate professor of English at Salisbury University where he is the director of graduate studies in English. He is also an editor of The Shore Poetry. He received his M.A. from University of South Florida and his Ph.D. from the University of Missouri.

JN What, if any, particular responsibilities do you think younger and up-and-coming poets have that are specific to that group?

JKA That’d be honesty. I think. Younger/up-and-coming poets owe nothing but the responsibility of being honest to themselves and their craft. And this could range from abiding to laid-down rules to following their instincts, i.e. being open to making their own mistakes, to the question of audience; realizing, in my opinion, that any audience outside of themselves is, could be, secondary.

It is important—and I say this also to myself—that they question, thereby distrust, everything they know of language, whether domestic or foreign, if they must exist, survive, thrive, in it. And I say this because I am of a generation whose experiences cannot be completely expressed in their mother tongue. I say this because I feel cut off, I feel denied an intimate tongue, I feel like a vagabond.

However, through poetry, I’m always curious and trying to enter into the intimacy and primacy of language I feel the plunder and violence of history has snatched from me. I seek a new English that expresses the feelings and consciousness and desires entirely human, African, Igbo, and I feel younger poets owe their voice, their craft, the medium through which they interrogate all of these, a similar awareness.

JN Who are some younger poets you like to read and would suggest to others?

JKA I am most excited about the new crop of young Nigerian poets whose diversity of voice and history primarily occupy the country’s literary space.

I am excited to mention poets such as Chibuihe Achimba, Ebenezer Agu, Chisom Okafor, Logan February, Precious Okpechi, Michael Akuchie, Chiamaka Onyenekwe, Pamilerin Jacob, Kechi Nomu, Hauwa Shaffi Nuhu, and Rotimi Robert, amongst others, whose poetry chapbook, Bipolar Sunshine, is forthcoming from Praxis Magazine Online Chapbook Series; a series I’ve, over a few years, had the privilege of editing with the American poet, Laura Kaminski. Also, I feel this list wouldn’t be complete if I do not mention the young Nigerian poet, Chukwuemeka Akachi, who showed remarkable promise, and was my friend, until his death by suicide several months ago.

There are also books by Romeo Oriogun and ‘Gbenga Adeoba forthcoming this March from the African Poetry Book Fund (APBF), and I am excited about them, especially Oriogun’s, since we started out together several years ago, basically, posting our poems on Facebook before any real recognition came.

I am especially floored by these poets’ obsession with looking inward as a form of activism. How the body, its virtues and faults, does not go unnoticed, and fascinatingly so. How commentary on the individual is, by wild extension, commentary on the society. And I am even more grateful that I am one of and exist in a space as them.

JN What are the most pressing aims of your own work? Briefly, how do they manifest in the featured poems?

JKA I am interested in the complexity of memory, how it interferes with and alters history, whether private or not. And this is quite evident in what I tried to achieve with “Sugarcane Chewing Days,” which, at its very root, is a love poem to boyhood; to the varied eccentricities that made it bearable and not, worth having or not.

And I say tried because to try is what I am most certain of in my process of starting and/or finishing a poem. I have said memory because it is the how, where and why of existence; the most palpable proof (and I’m taking quite the risk with the word palpable here) that the body, the mind, exists.

But more importantly, the autobiography of the mind, i.e. the psyche and self, how they culminate in the body to eventually become the body, are forefront in my work, especially as they relate to my own struggles with mental illness. This is to say that inspired by my own boredoms, solitudes, and bizarre trains of thought, I attempt and am moved to document the politics, private or otherwise, of the individual’s mind as seen by the individual themselves. And this can be seen, I hope, in the way the persona in “Boulevarde to Being Frank…”, for example, attempts to examine their selves through an unparalleled stream consciousness.

Boulevarde to Being Frank & Half Found Out

A newborn parting its way into the world

I weep with the shame of being

found out. I fear this begins for me the end—

slice of apparent light ungathering

—briskly—to a languorous crust. The hammer

of craft refuses to come down on me, so that

I am bemoaned—rust, a deliberate

fade, in the rain; nine inches &, make of this

what you will, no Christ nailed.

Yet by saying them out loud, we make

of our falsehoods a virtue more sonorous

than untrue. If there’s no truer wit to living

than living at all, nothing bleeds

internal abandon steadier than a life lived

in self-secession. The grief eventually lifts

like all things destined to perch, & I am left

standing in the empty hallway

of myself, a woman—nightmare-in-braille

one laboured echo away, masturbating to a mirror

of her own murder, her breathing an empty orchestra.

I walk in &, backing the mirror now, she gestures

to my mouth where her fingers have been.

A quiet life, a purr, surrendering to an end—

a sound more animal—& alive, than itself.

Sugarcane Chewing Days

for Arome

The road to St. Murumba’s bursts open

before us, the entrails of a beckoning god

in the sun. A man pushing a sugarcane truck

pushes the rest of our lives down the road

towards us. We consider it for a sleight of seconds

the time it takes to offer a prayer intention, or burn

through an entire calorie; consider what reoccurs: break

fast. Loss of hair, of love. To long for a pain

that paralyzes, that leaves room for no one else

but the myth of us, then indulge it armed

with nothing but loose change shrugged

into our pockets. Where else—if not in the body’s

black box—could we have cradled each currency

of our boyhood? For whom other than the road’s

keepsake did we leave a trail

of days like sugarcane husks sucked clean

of their sweetest venom? Everything we did

we did in pursuit of love & other troubles

uncalled-for. Everything we loved we left. To the remorse

& mismarriage of time—a comet that never will return.

& this was before evening came with its mosquitoes

a rioting halo, like interrogations of faith, just above

our heads; before the gunfire’s interlude scattered us

a herder’s most priced flock, in different directions.

Above us, a Caravaggio. White collared crows

elegiac against a bottomless sky.

Charlotte Covey is from St. Mary’s County, Maryland. She currently lives in St. Louis, and she earned her MFA in Poetry from the University of Missouri -St. Louis in Spring 2018. She has poetry published or forthcoming in journals such as The Normal School, Salamander Review, CALYX Journal, the minnesota review, Potomac Review and Puerto del Sol, among others. She is currently a poetry reader for River Styx.

JN What, if any, particular responsibilities do you think younger and up-and-coming poets have that are specific to that group?

CC I don’t believe younger and up-and-coming poets necessarily have responsibilities with their art, as it implies that art must have a larger purpose and cannot strictly be for the pleasure of the artist. However, I do believe it is important for young and up-and-coming poets to support each other and rejoice in each other’s successes. Writing and publishing can become very competitive, and people can quickly become more interested in being out for themselves than in the larger writing community. I also think it’s important for younger poets to support smaller presses and online journals and speak out against the gatekeeping and elitism in a lot of markets. Creating and marketing poetry that reflects the diversity and experimentalism of our time is important, and it also can hopefully make poetry more accessible to young people who would otherwise be uninterested, as they are only taught and familiarized with older traditional works by a few well-known older writers.

JN Who are some younger poets you like to read and would suggest to others?

CC I love poems that experiment with subject matter and form, and these poets do that particularly well: Kathryn Merwin, Emma Bolden, Hannah Kroonblawd, El Williams III, Jacqui Zeng, Clementine Von Radics, Lisa Ludden, Lindsay Lusby.

JN What are the most pressing aims of your own work? Briefly, how do they manifest in the featured poems?

CC First and foremost, my aim is to create art that expresses what I am feeling and thinking. Writing as an outlet is important to me, and I believe it is one of the strengths of my work. I am also very interested in the work and lives of young women, as I believe that they are especially vulnerable and bullied for things they like or feel, especially if it steps outside of the norm. I want to create work that showcases these experiences and creates a space for very flawed, complicated, imperfect women who wish to confess things that may not be very nice or may even be immoral. I want to write for these women, and maybe confess things that they aren’t comfortable confessing yet. These two poems in particular have speakers who become involved with older men and who end up being punished or cast aside. The poem, “beautiful (an elegy),” has the speaker sympathizing with Catherine Howard. She is my favorite wife of Henry VIII, and her adultery and beheading are such sad stories to me, especially considering she was only seventeen when she married an almost fifty-year-old man.

beautiful (an elegy)

Catherine Howard was the fifth wife of Henry the VIII. She was only seventeen when she was married to the forty-nine year old king, and nineteen when she was beheaded for committing adultery.

Catherine— i was a little fool, too. we were only

children when they found us, got us

to bed. we thought it was great, grown

up fun, and it was. oh, it was. we wrapped them

‘round our young fingers and danced

in the rain. we licked our lips

just right, stripped under stars when

we knew they were watching. it was magical,

in a way, knowing girls like us could be

queens, could dress up like

ladies and have men love us

and oh, did they love us. so much,

we could almost forget

how we really ended. how we lost

our crowns, falling to our knees

in prayer and mercy, begging

the way we swore we never would

again. but only for a moment.

we picked ourselves up, kissed our lovers

goodbye (if we could, in back rooms and sacristies

and tear-stained letters sealed with salt and red

lips). we marched to

our dyings, held our hands

to the sky, said, life is very

beautiful, and it was.

covet

somewhere, she is entering

the house, your house,

the one where you breathed

as one and carved children

out of your combined bark, roots

mixing into something you can’t tear

down (but i know you try). i am

something of a wall-fly creeping, you

always flinching when i come

too close. i keep

thinking how she and i both have

blue eyes and how she was my

age when you married her, but now

it’s twenty years later

and i’m just here, each night

we spend together nothing

but a second roaring

twenties for you, making

something of me, my newness,

your middle-age waxing

and waning across my breasts, while your sons carry

her eyes and your name, and i will never have

that, will never place your fingers to

my stomach, no roots of our own to grow.

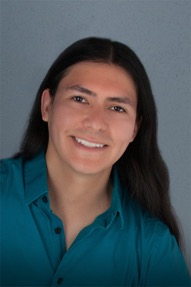

Benjamin Garcia’s first collection, Thrown in the Throat, was selected by Kazim Ali for the 2019 National Poetry Series (Milkweed Editions, August 2020). He works as a Sexual Health and Harm Reduction Educator throughout the Finger Lakes region of New York. His poems have recently appeared in The Missouri Review, American Poetry Review, and New England Review. Find him online: @bengarciapoet on Twitter or benjamingarciapoet.com.

JN What, if any, particular responsibilities do you think younger and up-and-coming poets have that are specific to that group?

BG I don’t know that this is a responsibility, per se, but I think up-and-coming poets have a chance to change how some things have traditionally worked in publishing. I’m thinking of the success of the Undocupoets Campaign, which was led by Marcello Hernandez Castillo, Christopher Soto, and Javier Zamora, in getting the majority of first-book contests to remove citizenship requirements. I’m thinking of spaces carved out by Tanaya Winder, Peter Laberg, Stevie Edwards, Jasminne Mendez, and other wonderful editors/organizers/curators/activists.

One area where I think we can still improve is our fixation on age when it comes to writing. I know, I agreed to be part of a feature called “5 under 35.” Call me a hypocrite or an ingrate. I’m not trying to knock Plume or any other venue that might have such features. But these parameters are to the exclusion of other up-and-coming writers—writers who may have come to writing later in life, or with life circumstances that have prevented them from dedicating the same time to writing, or haven’t had the same luck in mentorship or publication, or, or, or.

My point being, that sometimes these lists can make people feel that if you haven’t received a certain kind of “success” by a certain age, you’re not welcome or that you’ve failed somehow. But because youth and “newness” is one of the only points of leverage up-and-coming writers have sometimes, it’s hard for younger folks to argue against opportunities that were seemingly created just for them. However, it’s important that we question our obsession with youth and become more supportive of up-and-coming writers at whatever age they happen to be.

JN Who are some younger poets you like to read and would suggest to others?

BG Some up-and-coming poets I recommend: Casandra Lopez’s Brother Bullet and Sara Borjas’ Heart Like a Window, Mouth Like a Cliff were two of my favorite first books of 2019.

Writers whose first book I look forward to, when they’re ready: Christopher Phelps, Alex Chertok, Lauren Espinoza, Paige Quiñones, Jesus Valles, Suzanne Richardson, Imani Davis, Eduardo Martinez-Leyva, Omotara James, Silvia Bonilla.

JN What are the most pressing aims of your own work? Briefly, how do they manifest in the featured poems?

BG In my forthcoming book, Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed, August 2020), one of my aims is to help destigmatize queer ways of being through sex-positive poems. Another: to not reduce queer experiences to a singular narrative.

But if I’m honest, my most pressing concern when I’m writing poems is sound. Is this thing fun to read? I want my poems read out loud.

Non-monogamy

What’s in a name I can’t say, but—and this is just a guess—even if a rose did smell as sweet by any other, I’m willing to bet a shitballsnot flower would garner fewer gardens. There is something like a word inside a word in names. Take for example the word know. To know someone is another way to say you fucked. You can deny it, n—o sits in the middle and who knows what k and w are doing. Jiggle a letter here, and slide a letter there, and get rid of what is silent. You get the word own. And to be thoroughly fucked is to get owned. Meanings under meanings are called subtext, and words under words are called lies. I might sleep with twelve-hundred men, but who could know me more than you?

Curing the Body

As bacon must render

before it will crispen.

And fruit must bitter

before it will sweeten.

A turgid plum will prune;

a fig, a date, a nut, a pit.

A cake must be bitten

before it is eaten. You

must cut down the wheat

for bread to be risen.

The earth must frost

for tulips to up.

And the lake must lock shut

before stepping foot.

A loss must be felt

before it will lessen.

The heart is a grape

life sucks to a raisin.

Sneha Subramanian Kanta has been awarded the first Vijay Nambisan Fellowship 2019. She is the Charles Wallace Fellow 2019-20 at The University of Stirling, Scotland. She is the founding editor of Parentheses Journal, and reader for Palette Poetry and Tinderbox Poetry Journal. Her chapbook Ghost Tracks is forthcoming with Lousiana Literature (Southeastern Louisiana University).

JN What, if any, particular responsibilities do you think younger and up-and-coming poets have that are specific to that group?

SSK It is important to be true to your work, and develop a keen sense of self-awareness. I also often notice younger poets be more susceptible to unkind, flippant criticism. While there’s nothing wrong with keeping an open mind and realizing that there is, and will always be, plenty of scope for improvement, there’s always personal discretion one can put to use. I’d also say that dedicated time given to writing and revising is important. Besides that, be kind, generous, and cherish your readers.

JN Who are some younger poets you like to read and would suggest to others?

SSK I adore so many poets, and it would be difficult to list all their names here. I have carried the chapbook, What Bodies Have I Moved, by Chelsea Dingman across two continents and two fellowships; the book is a nugget of wisdom for me. I adore Paige Lewis, Devin Gael Kelly, Fatimah Asghar, Lindsay Lusby, Jill Mceldowney, Hannah Dow, Levi Todd, and many more. I’m also incredibly delighted to be a part of Palette Poetry and Tinderbox Poetry, where I’m a reader, as I get to read a lot of intriguing work. I’m the Founding Editor of Parentheses Journal, and we cherish the works of our writers.

JN What are the most pressing aims of your own work? Briefly, how do they manifest in the featured poems?

SSK I’m interested in exploring subterfuge ideas, the soliloquy, environment, landscape, and their manifestations in language. The ideas for these poems arrived through during my time as a Charles Wallace Fellow at The University of Stirling. The poems also seek to explore language as a means of fostering inclusiveness. The idea of interconnectedness across beings is writ large in these poems.

ghost sationem

(i)

a gleam of sunlight

on the lake

an iconography of ghosts migrate

through sunflower fields

rows of houses churned

into a prayer

sleet of lime-green moss

grow over ghost boughs

ghosts intermingle with waterfalls

over the riverbed

flowers engrave the earth

across the divisions of a chasm

beyond the route that leads to an ocean

ghosts crawl by willowherbs

the bones in their wrists made of dead

ocean creatures

(ii)

past a flaking ocean-bed weaving

carcasses with body out of dream

& dream out of encasings of a pulse

the sun is pushing dead flowers on earth

facedown into the umbra of an eyelid

with its oblong magnitude as an eclipse.

ghosts without maps turning fate on its

head exploring outer limits of astronomy

rest beyond the elliptical symmetry

in a home made out of leaf plumes

rising as foliage thickens into a storehouse

of light. ghosts defying gravity fly over

snow-capped mountains casting a tributary

of flowers for an infinite variable parallel

to ether. amaranthine blossoms in a valley

of quiet. chrysanthemums unfurl at dawn

as ghosts collect cloves from sheaves

psalm: a canary singing while falling snow

gathers on the ground & ghosts mitigate

siroccos to traverse beyond the horizon

(iii)

membranes a gathering of dead-leaf butterflies

auroras of ghosts in the matutinal lightshow mist

chipped walls over orchards of harvest

along a crepuscule dimming iridescent memory

lost things return as variables holy offerings

sky windblown into fragments of lint-bandages scatter

ghosts watching immaculate rivulets through rain

the prospect of a fading melody collect raindrops in a vial

fumes of smoke stretching through the bone marrow

from a window a synthesizer erupts into waves of static

(iv)

tercets of ghosts rising against humid air into an abyss. before the reflection,

an idea of the ligaments joined to make a body. the muscle tissue swallows

rain, spangled with dew from condensation. ghosts moving across road-signs

along prairies walk into an open field. when the body resurrects, a tide gains

momentum from the ocean beyond the place mapped at an interlude. offer

to unname a thousand flowers & see them as birthing themselves from the

petal, & praise their mutations. if there is an end, it will come to us in flowers.

Among burials, the bracken yields

against the sheen of summer. Seagulls pick

insects like a speckle hidden in the grass &

devour them as intact amulets. Spring sprouts.

Beside a three-lobed water-crowfoot by the lake,

a leftover carcass of a fish glows in the sun.

Ghosts rise in silence from the topsoil sediment.

Hepaticas emerge with pollen & nectar, & bees

appear to satiate their hunger. Sparrows eat

stray petals on the ground. A hunger amid

decomposing bones. An omen of bare trees.

The eye of a vulture staring at its prey. Animals

that call themselves human. Animals as patron

saints guarding a place. Birds that transport

seeds across coordinates, flying against the wind.

Light harnesses every foundling into a safe nest.

Ghosts walk by a sea hooked on to high tides.

The landscape bleeds into myriad phalanxes

from its wound source. The hollow sounds

echoing in our cochlea. Corpses wash away on

empty shores. Ghosts hymn hallowed choruses.

Animals skinned alive with tongs of shears.

Ghosts passing their silent sermons through burials.

The hue of a coleus like oxidized blood. Ghosts,

with open mouths, fasting. The slow harp of a cleaver.

Lindsay Lusby is the author of the poetry collection Catechesis: a postpastoral (The University of Utah Press, 2019), winner of the Agha Shahid Ali Poetry Prize, judged by Kimiko Hahn. She is also the author of two chapbooks, Blackbird Whitetail Redhand (Porkbelly Press, 2018) and Imago (dancing girl press, 2014), and the winner of the 2015 Fairy Tale Review Poetry Contest. Her poems have appeared most recently in Gulf Coast, The Cincinnati Review, Passages North, The Account, and North Dakota Quarterly. Her visual poems have appeared in Dream Pop Press and Duende. She is the Assistant Director of the Rose O’Neill Literary House at Washington College, where she serves as assistant editor for the Literary House Press and managing editor for Cherry Tree.

JN What, if any, particular responsibilities do you think younger and up-and-coming poets have that are specific to that group?

LL I think younger or newer poets have a two-part responsibility: first, to learn as much as possible about the history of poetry and the intricacies of the craft as it is and has been practiced; and then, to push and play with the preconceived boundaries of poetry in terms of both form and content. I think it is essential to learn a craft before you start to break its rules. But once you understand their history and intent, it is also essential to test those limits with your own set of history and intentions. I don’t believe that this is or should be practiced exclusively by younger poets, by any means, but I do believe it is our responsibility more than any other group. Play and experimentation are essential to keeping poetry a living, breathing medium that continues to embrace the human world and meet us where we are, not just where we once were.

JN Who are some younger poets you like to read and would suggest to others?

LL There really are so many, but here are just a few: Sara Eliza Johnson, Jennifer Givhan, Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach, Nancy Reddy, Emily Skaja, Emilia Phillips, Susannah Nevison, Sarah Blake, Alyse Bensel, Rosebud Ben-Oni, Aldo Amparán, E. Kristin Anderson. All of these poets exhibit a sense of play with language and subject that always reels me in. And Rosebud’s science poems! You’ve got to check out all of these poets.

JN What are the most pressing aims of your own work? Briefly, how do they manifest in the featured poems?

LL A truth that I’ve slowly been coming to terms with is my fascination with depictions of violence, which is something about myself with which I’ve never been quite comfortable. I’ve found that my main preoccupation in my poetry is a specific fascination with how women are transformed by violence—in fairy tales, in horror, in saint & martyr narratives. Every woman has to contend with the ever-present potential for violence in her life, something about which it seems we have little control. My aesthetic is the postpastoral—a celebration of the beauty inherent in the darker side of the natural world—of monstrosity, mutation, deformity, decay. In these two poems, death and decay are certainly at the forefront, but they are depicted as a continuing transformation of the body.

They linger in a perpetual dream state.

—Poltergeist (1982)

We begin

a canary in a cigar box,

buried in the backyard

under dandelion & clover:

yellow for wilt &

yellow for wane.

Roots stitch through us

new arteries,

capillaries fine

as the down of deadnettle

dissecting & suturing

our bodies like topsoil.

We see a light & we count

until we hear

anything at all.

Where else would we go

than this grave & grassy bed?

How else should we sleep

but like the dead?

On Forensic Files, Husbands Kill Wives & Wives Kill Husbands

When they find her, she is already

as bone as a winter oak—

bare of all but the birds’ nests

in her hair—as pitted as the moon

phosphorescing through its branches.

The true thing is that which glows

in the dark. When they say a case

goes cold, they mean snow gone gray

as gunpowder on gravel, they mean

the only tracks untrampled are

their own. As surely as dusk deadends

into night, there’s no way out but

to forage in the underfrost,

to find a good man

in the ground.

Sarah Uheida was born in Tripoli, Libya. She is 21 years old and is currently busy with her undergraduate in psychology and linguistics at Stellenbosch University. She learnt to speak English at the age of 13 when the civil war in Libya forced her to start a new life abroad. She is compiling a poetry collection Beautiful Women and Where to Find Them, and Penning down her memoirs of the war, A Girl’s Plethora of Knives. You can find her strolling through the streets of Stellenbosch and reading Sylvia Plath. Her work features in the literary journals New Contrast, Blindeye, Eunoia Review, The Shore, and Fresh.Ink.

JN What, if any, particular responsibilities do you think younger and up-and-coming poets have that are specific to that group?

SU I think writing never feels like a responsibility for me. It is the responsibilities that we must carry out from day to day that lead to the sanctuary of writing. And maybe, in a way, that is our duty as young writers; to channel all the turmoil and tenderness of every-day living into something lasting – a modern artifact that the world can regard as tangible evidence of change, hopefully for the better. Literary proof that we are living, if you will. As young writers, another thing we owe ourselves is to keep writing, even if it feels like the audience is imaginary at times – perhaps especially then – because that is how we come to say what we are truly aching to say, without shying away for fear of rejection. We are so young and teeming with language, and all that we can do is to continue claiming our space, one poem at a time.

JN Who are some younger poets you like to read and would suggest to others?

SU Ocean Vuong is one of my absolute favorites; his writing embodies hunger and leaves you reeling with the uncertainty that encircles the truth. Another writer I truly admire is Amanda Oaks; her Where’d You Put the Keys Girl is an anthology I reread often and with just as much fascination as I had the first time. Jupiter Reed, Emily Jungmin Yoon, and Warsan Shire are also women whose work has captivated me to no end.

JN What are the most pressing aims of your own work? Briefly, how do they manifest in the featured poems?

SU Through capturing fragmentary moments, my words attempt to knit the threads of the past into a sliver of reassurance that there can be a tomorrow for survivors of war. What I wish to convey in my poetry is just how nonexistent the line between war and love is. Having escaped a war myself, it feels like my life is continuously dancing between the past and the present, which I believe resembles the way trauma distorts one’s perception of time. In “Imagine Wars, Imagine Bodiless Women” two women who are in love – or think they are – battle with a very human urge to self-destruct. I think that is a little like war, how illogical its nature is, really, and how it begins overnight and inexplicably. When I wrote “Small Fires & the Equivalent of Ease”, I think I was mostly reflecting on how fickle affection is, and how in order to save ourselves, we never truly give as much as we say we do so that when ruin catches up to us, we will have already “saved the leftovers of our hearts for the aftermath.”

Imagine Wars, Imagine Bodiless Women

She spilled the wine

said honey let something darken us;

reached for the ammunition I keep under the bed

for when the night negates our dreams

and I have to blow up something tangible

so with her hand on the back of my neck,

I will call someone who cares, only to hang up

hurry across plains in a maroon dress I borrowed,

wear in case of war;

too proud to run, we throw our heads back

last mouthful of bourbon

under a hail of bullets

I crawl; she steps on my dress,

the field is a cigarette half lit

she says I left too much behind

so I shrug her off

like a winter sunset;

underwhelming, uncalled for.

she retreats like bravery

lowers the stakes,

love always sheltered us

but I never did find a reason to stay;

only my explosive nature

only this poem’s implications.

Bound to break,

I trudge on, lilac falling out of my mouth

till I reach the other side,

turn around

make my way back under a sulphide sky

even leisurelier this time.

Small Fires & the Equivalent of Ease

The sunset’s whereabouts; vague

and if I do not look where I’m going,

I will meet you there.

it’ll be like petty theft,

hunger

and it’ll be like the hurt never sinks in,

it will be like love

like fib & fable

hallucinations

like the way you take my hand,

candyfloss

candles lit below our mouths

spectral

It’ll be like the light leaking down your neck,

and the world begging to be let in

deathless

But you will skip right past the living,

Uncap whiskey & fetch glasses the way you did that first time

More,

pouring forgetfulness

that’s perfect thank you,

your eyes will blank out the way they do

when you are looking at the gaps between the moments worth writing about

and you will say:

I have loved the wind and lamented. I have died mid-kiss. I have saved the leftover parts of my heart for the aftermath.