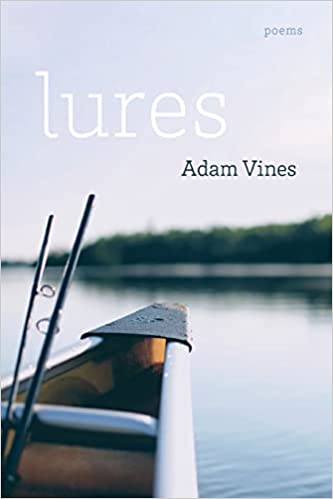

Adam Vines

Lures

2022. LSU Press.

Paperback. 58 pages.

Reviewed by Chelsea Wagenaar.

If you read all of Adam Vines’s new collection, Lures, and at the end of the book close your eyes and try to picture in your mind’s eye the book’s signature image, you’d likely see this: a man in a boat on a body of water. The image is salvific, biblically resonant—think Noah, think infant Moses floating downriver in his woven basket—and given the “Bible Belt” culture and cadence of some of the language in the book, it’s apt. To be out on the boat is to be saved, briefly, from a deluge of one kind or another. Fishing, in Vines’s hands, becomes not just a form of relaxation and escape, though it is that, but more deeply an act of remembrance, of ceremony and ritual. Religious. Only on the boat could he witness his father relax, as

he’d stretch his legs and dig his heels

and match a Lucky Strike to life…

We’d be all right.

I’d dig in deep like him and hum a hymn… (from “My

Father’s Rod: Fishing the Skinny Moon”).

Being on the boat takes on elegiac qualities in many of the poems, as in “River Elegy,” in memory of Jake Adam York. It’s richly musical and wistful, imagining a shared experience never to be realized:

so when we would have run

and re-livered that trotline by the skinny moon,

we’d have fire close when we skulled

back to the bank. Then over a skillet

of skeeting yellow cat fillets…

The river is its own religion, “where fish camps outnumber churches.” It’s a place that demands the same loyalty as kin, not a place you invite a mere acquaintance: “…on to the dirt road’s end / where my kin crawled out of the river, / where I would have cut and split / a seasoned white oak for your visit…” The image, elegiac in its conditional tense, conveys a grand hospitality in an inner sanctum. More than once while reading Lures, I was reminded of Seamus Heaney’s work (read “My Father’s Trowel” next to Heaney’s “Digging”), and “River Elegy” evokes Heaney’s “Casualty,” an elegy for a fisherman that likewise ends with a refusal of traditional forms of mourning, instead sending the speaker out on a boat where “you find a rhythm / Working you, slow mile by mile, / Into your proper haunt / Somewhere, well out, beyond…” Like Heaney, Vines connects the poetic act with fishing, but Vines’s means of connection is to infuse the music of the poem with the rhythm and diction of the devoted, practiced fisherman, as in these lines from “Our Boat,” another elegy:

You’d give me shit if I didn’t

fill the tank with one throw:

“lazy eight—I guess we’ll miss

the first-light bite” you’d say, when we both

knew that only old salts like us

who reckon this water like our children’s lies

could open a perfect eight-foot O

at low tide and miss the oyster bars cragging

the bottom with a speed retrieve—

While Lures is overall an outdoor collection, of fish and snakes and bait, a get-your-hands-dirty collection, Vines still incorporates the signature ekphrasis of his previous book, Out of Speech. “Euphoria of Belief,” after Bosch’s The Conjurer, is a classic ekphrastic poem. All you need are the poem and the painting side by side, and Vines’s patient, narrative attention illuminates the entire scene. I particularly enjoyed his description of the way the onlookers’ attention unfolds throughout the scene:

Most other folks are mesmerized,

some with the pearl, the monkey’s studded strap,

its ear-holed hat, but one knows well

the conjurer and snakes his hand across

a Lady’s chest and to the jewels

that hang between her breasts.

By contrast, “Anti-Aubade”—one of several love poems in Lures—folds the poet’s ekphrastic attention into the scene with the lovers. “Anti-Aubade” begins, as many of the poems do, with description of landscape, the exterior world, which provides a segue to the interior. (Simultaneously, we can be in awe of its 23-line opening sentence, a testament to Vines’s deftness with all kinds of rhythm.)

A crow gouges the lead sky

now smeared pewter and tungsten…

the crow’s eye and caw

cut back to us after it lights on that limb

broken free at the elbow, nubbed

like a gray-veined bust,

how nature might suppose

Balzac caught in his fury…

Here Vines invokes Rodin’s sculpture of Balzac, in which, beneath his head, Balzac’s body famously appears as one undifferentiated trunk-like figure, swathed in on itself, without distinguishable arms or legs. I had not previously seen the sculpture as arboreal, but after reading “Anti-Aubade,” I have trouble seeing it any other way. One of the charms of the poem is the seamless way Vines connects the miraculous nature of sculpture, to bring likeness from stone, with the two lovers’ entwined, one-fleshed form: “thick arms, necks, our branchings, / knuckles, cusps and curls and braids, // our inward foldings, our eyes cut away / from one another because they must…”

I’ve scarcely touched on the short poems that punctuate the collection (“Remains” is my favorite), nor the humor—that rare poetic quality—that sneaks into its pages, nor the title poem, with its stunner of a last line. But Lures is a book of mature work, wise and unassuming, by a very fine poet, and as the title suggests, it will tempt me into its world for a long time to come.